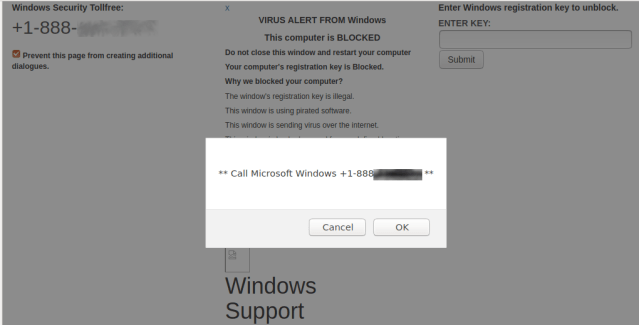

Technical support scams are among the most pervasive forms of Internet-powered fraud. Preying primarily on less sophisticated computer, tablet and smartphone users, tech support scammers use fear and misinformation to convince their targets that they have become the victim of some sort of malware and coerce them into purchasing unneeded (and sometimes damaging) software and services to “protect” themselves.

A common method of catching less educated device users is the use of fraudulent web “advertising”— in the form of pop-up windows or redirected web pages that attempt to emulate system alerts. A class of these fake error websites makes it more difficult to get away, using HTML and JavaScript that take advantage of design bugs in the browser’s code. This type of bug is often referred to as a Browser Lock (browlock) bug.

Browser developers, including Mozilla, have made fixes in the past to prevent such abuses. However, we’ve recently found a Browser Lock bug that overcomes those efforts. The bug, CVE-2020-15654, was reported by SophosLabs to Mozilla and fixed in Firefox version 79. In this report, we’ll analyze three types of Browser Lock bugs that have specifically affected the Firefox browser, what Firefox programmatic internals made them possible, and how they were fixed.

Raising the (false) alarm

Browser Lock bugs are in themselves not severe security vulnerabilities. They only have a temporary, superficial effect on the browser when exploited, and can be easily remedied by an advanced user. But their persistence may convince less sophisticated users that the alerts they present are real—and lead to an actual compromise security, aided and abetted by them.

The classic fake error website—the simple pop-up window—is mostly effective in ensnaring the less computer-literate. But those with slightly more experience are more attuned to the dangers of internet fraud —those who realize they did not actually win a new car for being the one millionth visitor to a website, or that the person seeking their help transferring a fortune in return for a cut is not really a Nigerian prince—will more instinctively be skeptical of them. They might reflexively attempt to get rid of the fake error page, by either navigating away or closing the browser.

If they manage to make it go away, they will be quick to dismiss it as bogus despite the alarming content of the fake error. But if they can’t, they may be less sure that the alert isn’t real. That’s where Browser Lock bugs come in. They’re not really new as a class of scam—some versions have been around for years.

The Deceptive Custom Cursor bug

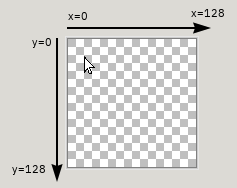

One of the oldest tricks scammers use to fool victims is the abuse of the “CSS cursor” feature in browsers—commonly known as the “Evil Cursor” attack. The CSS cursor property allows for a web developer to modify the way the user’s mouse cursor appears while it is within the confines of the web page. A custom image (up to 128×128 in size, in the case of Firefox) can be defined in the CSS property to serve as the mouse cursor instead of the default one:

The same CSS property can be used to control the cursor’s “hotspot”—the exact (x,y) coordinates for the offset inside the custom cursor image where mouse clicks should be registered. The origin point (0,0) is the top-left corner. In the typical cursor (such as shown in the picture above), the hotspot is meant to be at the pointy tip of the cursor.

The flexibility in being able to design the cursor image to appear as we wish, coupled with the ability to define an arbitrary hotspot for it, is a ripe feature for malicious actors: it’s easy to define a custom cursor whose mouse clicks register elsewhere than it appears to point to.

The classic Evil Cursor attack employed a large custom cursor image with the appearance of a typical cursor at the top-left corner of the image, but with the hotspot point at the bottom-right corner of the image. This way, attempting to click the Back button, Address bar, or the window’s Close (X) button will result in a dud click that does nothing, resulting in an illusion of a Browser Lock.

This bug was reported and addressed in Mozilla Bug 1445844, back in 2018.

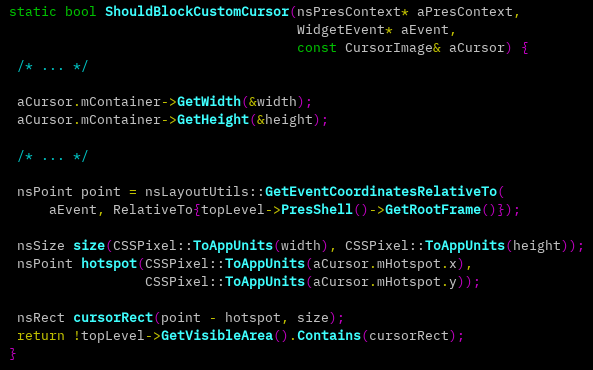

In the fix issued for this bug, the primary addition introduced to the browser’s source code is the function ShouldBlockCustomCursor:

As the name suggests, this function implements logic to help the browser determine whether the custom cursor definition should be honored or not, given the current position of the cursor on the screen.

The following are the terms and variables used in the function above:

The portion of the browser window where the current web page is displayed, usually everything just below the address bar and the various toolbars, is referred to here as “frame” and is returned by topLevel->PresShell()->GetRootFrame().

Throughout the function, the frame is treated as a two-dimensional plane, with its origin point (0,0) being the top-left corner of the frame.

Variable point is the current (x,y) coordinates of the custom cursor’s hotspot on the frame’s plane. e.g. this value would be (0,0) when the custom cursor’s hotspot is pointed at the top-left corner of the page.

Variable size is the width and height measurement of the custom cursor image, e.g. 128×128.

Variable cursorRect is a rectangle on the frame’s plane. The rectangle represents the area of the custom cursor image, with its dimensions being size, and its base top-left corner being the value of point, normalized to a hotspot of (0,0). In other words, a “correction” is made for the sake of this calculation if the custom cursor’s hotspot is set to anything other than (0,0).

This means that if the custom cursor image dimensions are 128×128 and its hotspot is set to (110,120), cursorRect will be a 128×128 rectangle with the base top-left corner being point, except shifted 110 points leftwards, and 120 points upwards.

Finally, the function checks if cursorRect is fully within the frame’s plane.

If the custom cursor’s hotspot has been defined as anything other than (0,0), and the current cursor position is sufficiently close to the X=0 or Y=0 lines (the left and upper borders of the frame), cursorRect would end up occupying negative (x,y) coordinates, and therefore not fully within the plane.

In that case, the function returns true, meaning the custom cursor is “blocked”, and the default cursor is used instead.

Infinite Downloads of Blobs bug

Another Browser Lock type of bug was reported and addressed in Mozilla Bug 1438214, also in 2018.

The original reporter encountered the bug in a live fake error website. A simplified version of the offending JavaScript code is:

function download() {

var b = new Blob;

var o = URL.createObjectURL(b);

var l = document.createElement("a");

l.href = o;

l.click();

}

while (true) download();

Essentially the code above is endlessly creating and triggering the downloading of Blob objects using Anchor (<a>) elements.

From the look of it, it’s evident that this is a Denial of Service type of bug, because it’s never-ending and will surely cause heavy CPU usage in the browser to the point of causing the page to become unresponsive.

A scenario where a web page causes the browser to become unresponsive and does not allow the user to (easily) browse away, can essentially be considered a Browser Lock bug.

However, since browsers are designed to run any arbitrary script given to them by a website, they have long been taking into account the possibility of scripts (whether intentionally or not) overloading and freezing the page.

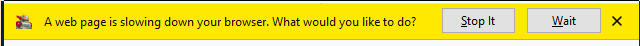

In Firefox, a “Process Hang Monitor” was introduced to counter this problem. When this monitor detects that a page is unresponsive, it will pop up the following bar just above the page:

This bar, also known as the “Slow Script Dialog”, gives the user the option to stop JavaScript execution, (hopefully) resolving the unresponsiveness.

What sets this specific bug apart, is that in affected versions, the yellow bar never pops up after the page is loaded, despite it being totally unresponsive.

It turns out that each Blob download action leads internally to a CPU and memory heavy IPC message being broadcasted to all processes of the browser, most importantly the main firefox.exe process.

With the IPC messages reaching the main process and burdening its resources too, the Denial of Service condition is spread to it, and the yellow bar feature which is partially implemented in the main process is prevented from functioning as designed, resulting in a Browser Lock.

The fix employed by Mozilla was to simply remove the code responsible for IPC broadcasting of Blob downloads. The code had already become redundant due to previous browser updates, so it was not needed.

Deceptive Custom Cursor bug returns – CVE-2020-15654

Earlier this year, we encountered a live fake error website that caused a Browser Lock effect on the latest version of Firefox at the time.

The website consisted of a moderately sized HTML file containing JavaScript code and a CSS file.

Since Browser Locking is clearly an undesirable condition that likely points to a bug present in the browser’s code, we started investigating the web page in order to find the root cause, so that ideally it can be reported and fixed by Mozilla.

Here’s how visiting this fake error website looks in action:

Shortly after the web page is loaded (around the 4 seconds mark), you can see the mouse cursor suddenly gets jerked to the upper-left while also simultaneously changing its appearance, from a crosshair type to a typical cursor type.

This is the moment when a custom cursor image is loaded. The sudden movement is due to the upper-left offset of the cursor inside the custom cursor image, in line with the original Deceptive Custom Cursor exploits.

The blue circles that appear in the video denote a left mouse click. They show that after the web page is fully loaded, the location of the clicks is no longer synchronized with the mouse cursor—when the user tries to click a button, the actual click is on something else.

Another thing we see is that the right side of the screen is seemingly inaccessible by the mouse pointer. In fact, when the cursor appears to be stuck and cannot be moved further to the right, the actual cursor hotspot is at the rightmost position. This effect only happens when the browser is in full screen mode.

Lastly, when the yellow “A web page is slowing down your browser” bar appears, it can be seen that its buttons are also covered by the deceptive custom cursor effect and appear to be un-clickable.

Bypassing the old fix

It’s obvious from observing the browser’s behavior that this page made use of the deceptive custom cursor method. But as we noted before, the deceptive custom cursor bug is well-known and was supposed to have been fixed back in 2018— and therefore, it should not be reproducible in new Firefox versions. So, what went wrong here?

We know that with the previously discussed fix applied, the function ShouldBlockCustomCursor would be regularly called to check and mitigate deceptive custom cursors, but it’s clearly not working as intended in this case.

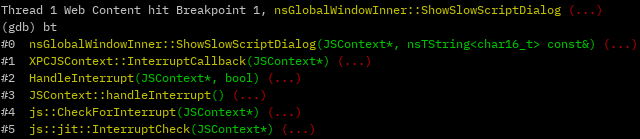

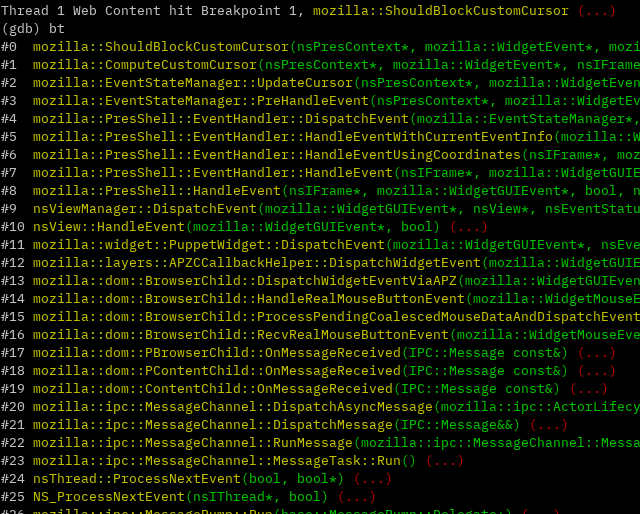

To see what was going wrong, we ran the browser under a debugging session, attached to the Web Content process that corresponds to the relevant page (each tab has its own Web Content process), and set a breakpoint in the function:![]()

With this setup, we visited the offending page, moving and clicking the mouse around, to find that the function is not being called at all.

Somehow the flow to the function is prevented. For reference, this is how the backtrace looks when the function is called in a legitimate flow, when the mitigation is working as intended:

Here we can see the chain of function calls that end up triggering the mitigation function:

Upon moving the mouse, the parent process (the main firefox.exe process) sends a RealMouseMoveEvent message with event type eMouseMove to the page’s Web Content process.

On the Web Content process’s side, this message is eventually received and processing begins in NS_ProcessNextEvent.

From the low-level messaging interface between “Parent” and “Child” (ipc::MessageChannel), the event bubbles up to the higher-level PresShell (Presentation Shell) interface.

In EventStateManager::PreHandleEvent, specific handling of eMouseMove begins. From there, functions that deal with cursors, and specifically custom cursors (if applicable), are called. Among them is ShouldBlockCustomCursor.

The source code responsible for calling the first function shown in the backtrace above (NS_ProcessNextEvent) in that same context is the following message loop function:

void MessagePump::Run(MessagePump::Delegate* aDelegate) {

...

for (;;) {

...

// This will either sleep or process an event.

NS_ProcessNextEvent(thisThread, true);

}

...

}

Going back to the debugger, setting up a breakpoint in NS_ProcessNextEvent and reloading the page, shows no hit on that function either. A typical Web Content process in the middle of a browsing session should see this function called pretty much non-stop.

So the reason ShouldBlockCustomCursor does not run is not the result of some cursor-related trickery that a clever attacker discovered and is using to bypass the mitigation. In fact, even the most low-level message loop mechanism is not functioning – IPC messages are not being received and processed.

The reason for this failure is hinted by the eventual appearance of the familiar yellow bar, signaling that the page is unresponsive. Upon inspecting the JavaScript code in the page, it turned out that the reason for this hang-up is a simple endless loop in the code.

Why would a JavaScript endless loop code cause the halting of the most basic message loop processing in the Web Content process? JavaScript code that runs within a web page, is executed in its Web Content process. Not only that, but it’s also executing in the same thread, named “Web Content”, where the relevant message loop is running.

So while JavaScript code is busy running, events such as “Mouse Move” are not dispatched, rendering the old Deceptive Custom Cursor mitigation obsolete. Thus, a “Browser Lock” effect can be achieved despite the old fix.

The new fix

After analyzing the bug, we reported our findings to Mozilla. Mozilla were quick to create and push a fix to their codebase, which went live in Firefox 79. The bug was assigned CVE-2020-15654: Custom cursor can overlay user interface.

The patch consists of just two lines of code added to nsGlobalWindowInner::ShowSlowScriptDialog, the function responsible for popping up the yellow bar:

// Override the cursor to something that we're sure the user can see.

SetCursor(NS_LITERAL_CSTRING("auto"), IgnoreErrors());

The code above simply sets the CSS cursor property to keyword auto (the default cursor), overriding any previous value. Since custom cursors are set up using this CSS property, any custom cursor configuration is now deactivated. Now when the Process Hang Monitor is triggered and the yellow bar we mentioned earlier appears, the mouse cursor is reset to the default one. The user is then able to easily escape the web page – by interacting with the browser’s buttons and navigating away as one would normally do.

The reason this fix works—and isn’t overwhelmed by the browser being busy with running JavaScript code, as the last fix was—is that the new fix’s code is not called by the message loop mechanism. Instead, it’s called from a JavaScript engine interrupt callback:

The JavaScript engine is designed to periodically interrupt JavaScript execution and allow for these callbacks to be invoked. By inserting interrupt checks into JIT compiled code, the engine ensures that the callbacks occur even in the midst of endless loops. The backtrace pictured above is an example of such an instance.

One of these aforementioned interrupt callbacks is XPCJSContext::InterruptCallback, which serves as the basis for the Process Hang Monitor mechanism. Every time this function runs, it calculates the time elapsed since the last completed NS_ProcessNextEvent call.

As mentioned before, in the case of the malicious web page in question, the message loop mechanism becomes “stuck” and NS_ProcessNextEvent calls do not complete. After some time of this, the “time elapsed” timer exceeds a timeout, and springs the yellow bar into action by invoking nsGlobalWindowInner::ShowSlowScriptDialog, the same function containing the newly introduced fix.

With this bug being fixed, the overall security posture of Firefox against Browser Lock bugs is improved, but it is hardly the end of such bugs in this, or other, web browsers. The good news is that the tech support scammers who set up these fake error websites bugs rarely innovate, and are generally not sophisticated enough to discover and make use of such bugs.

That doesn’t mean that less sophisticated users won’t still fall for these malicious sites, even if they can easily navigate away from them. The best way to prevent people from falling victim to these scams will continue to be raising awareness to them.