Earlier this month, we reported on a phishing scam in which the lure was “safety measures” against the Coronavirus (Covid-19).

In that attack, the crooks took you to a facsimile of the website of the World Health Organization (WHO), where the information was originally published.

On the ripped-off copy of the site, however, the crooks had added the devious extra step of popping up an email password box on the main page.

Of course, the WHO website wouldn’t ask for your email password – it’s a public information website, after all, not a webmail service, so it has no need for your email details.

The crooks were hoping that because their website looked exactly like the real thing – in fact, it contained the real website, running in a background browser frame with the illicit popup on top – you might just put in your email details out of habit.

Well, here’s another way that the crooks are using concerns over the Coronavirus outbreak, combined with the WHO’s name, to trick you into clicking buttons and opening files you’d usually ignore:

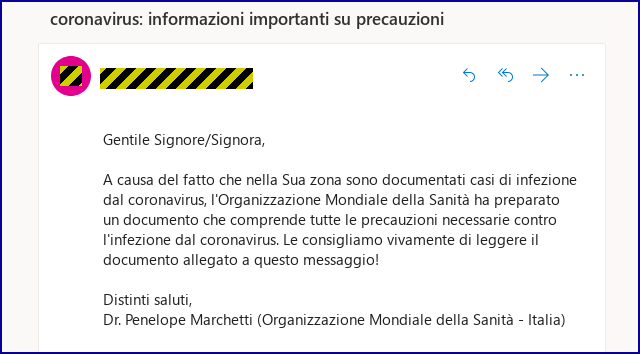

SophosLabs tracked this particular spam campaign in Italy, where the crooks have made it believable and clickworthy by:

- Writing the message in Italian.

- Pretending to quote an Italian official from the WHO.

- Referencing known virus infections in Italy.

- Urging Italians in particular to read the document.

In other words, the crooks haven’t just pushed out a blanket message trying to capitalise on global fears, but have given their scam email a regionalised flavour, and therefore a specific reason to act:

coronavirus: informazioni importanti su precauzioni

A causa del fatto che nello Sua zona sono documentati casi di infezione […] [l]e consigliamo vivamente di leggere il documento allegato a questo messaggio!

—

coronavirus: important information on precautions

Because there are documented infections in your area […] we strongly recommend that you read the document attached to this message!

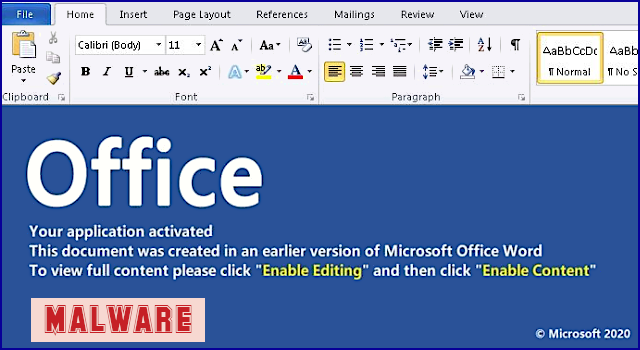

This time, there isn’t a link to a fraudulent website, but an attachment you are urged to read instead.

By now you ought to be suspicious, given that Word documents can contain so-called macros – embedded software modules that are often used to spread malware, and that are an obvious risk to accept from outside your company.

Indeed, Word macros – often used legitimately inside companies for managing internal business workflow – are sufficiently risky when they arrive from outside that Microsoft has, for many years, blocked them by default.

As you probably know, however, the crooks have learned how to turn Microsoft’s security warnings into “features”, as you see here:

The actual document – the part that isn’t dangerous, and doesn’t harbour the macro code – is the text with the blue background you see above, and it has been deliberately created by the crooks to look like a message from Microsoft Office itself:

Your application activated

This document was created in an earlier version of Microsoft Office Word. To view full content, please click “Enable Editing” and then click “Enable Content”

© Microsoft 2020

As reasonable as this sounds, DON’T ENABLE CONTENT!

The “content” you will activate by clicking the [Enable Content] button is not the document itself – you’re already looking at the document part, after all – but the macros hidden in it.

And the macros in this document aren’t anything to do with your company’s workflow – they make up the malicious software code that the crooks want to run.

SophosLabs has published a technical report on what happens if you run this macro malware, which involves a series of stages that ultimately result in infection by a well-known strain of Windows malware called Trickbot.

We recommend you read the Labs report to learn how a modern malware infestation unfolds, with each step downloading or unscrambling the next part, usually in the hope of breaking the attack into a series of operations that are less suspicious, one-at-a-time, than running the final malware right away.

Where have I heard that name before?

If you’re wondering where you’ve heard the name Trickbot before, it might very well have been on the Naked Security Podcast, where our resident Threat Response expert Peter Mackenzie has mentioned it more than once. (In the episode below, Peter’s section about malware attacks starts at 19’10”.)

LISTEN NOW

Click-and-drag on the soundwaves below to skip to any point in the podcast. You can also listen directly on Soundcloud.

Trickbot is dangerous in its own right – it started life as a so-called banking Trojan, a type of malware that tries to hijack access to your bank account.

These days, Trickbot is also very commonly a precursor to a full-blown ransomware attack.

By implanting Trickbot on your computer, the crooks get a foothold inside your network where they can harvest passwords and data and much more, as well as mapping out what resources you have.

Once they’ve squeezed all the criminal value they can out of the Trickbot part, the crooks often use the bot as a launch pad for their final act: a ransomware attack.

One ransomware family that commonly follows unchecked Trickbot infections is the malware strain known as Ryuk, whose criminal operators are notorious for asking for six- and even seven-figure ransom payments.

What to do?

- Don’t be taken in by authority figures mentioned in an email. This scam claims to be from an Italian WHO official, but anyone can sign off an email with an impressive name.

- Never feel pressured into opening attachments in an email. Most importantly, don’t act on advice you didn’t ask for and weren’t expecting. If you are genuinely seeking advice about the coronavirus, do your own research and make your own choice about where to look.

- Never click [Enable Content] in a document because the document tells you to. Microsoft blocked the automatic execution of so-called “active content”, such as macros, precisely because they are so often used to implant malware on your computer.

- Educate your users. Products like Sophos Phish Threat can demonstrate the sort of tricks that phishers and scammers use, but in safety so that if anyone does fall for it, no real harm is done. Sophos also has a free anti-phishing toolkit which includes posters, examples of phishing emails, top tips to spot email scams, and more.

Anonymous

they are not “so-called” macros, they are macros. Do you employ anyone that proof reads these articles?

Paul Ducklin

Technically, they are Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) subroutines. They’re also referred to as “content” (as in the [Enable Content] button mentioned above), and, indeed, as “macros”.

I used the phrase “so-called” to denote that the word “macro” is one of numerous monikers by which VBA code is informally known, even though a modern Word subroutine is way more complex and expressive than what was originally meant by “macro” when that word first appeared in software engineering.

IMO, that is an unexceptionable use of the word “so-called”, and an unexceptionable use of the word “macro”.

So: yes, we have editors. And, FWIW, I think they made the right decision, in this case, to keep the word “so-called” in the text, as I originally wrote it.

PS. If I were editing your comment, I would start with a capital T in the initial word “they”, and I would write “proofread” as one word. (The Oxford Dictionary lexicographers seems to prefer “proof-read”, but my own opinion is that the term has become self-sufficient enough to stand as a single unhyphenated word.)

Alistair W

This is the greatest response I’ve ever read

Anonymous

Out trolled a troll. We of the internet realm salute you sir!

Paul Ducklin

I get the OP’s point – they are indeed called macros and you are welcome to call them that.

But the word “macros” means such different things to different people (keyboard macros, m4 macros, and so on) – and most of those meanings describe features that aren’t fully-fledged programming environments in their own right. So for all that “macro” is an unexecptionable name, on a technical level it’s a bit like calling the keypad on your phone a “dial” when you are actually trying to focus attention on the fact that it’s not a dial, it’s a full-on app with a GUI made of buttons.