It’s only eight days since Apple’s latest and greatest macOS 10.13 release, better known as High Sierra.

But the first security update has already come out, and we suggest you apply it urgently.

The update is called High Sierra 10.13 Supplemental Update, detailed in the security advisory APPLE-SA-2017-10-05-1.

There are two bugs fixed; the facepalming one is described thus:

[BUG.] A local attacker may gain access to an encrypted APFS volume. If a [password] hint was set in Disk Utility when creating an APFS encrypted volume, the password was stored as the hint.

To explain.

APFS is short for Apple File System, Apple’s new way of organising hard disks that replaces the old (but still supported) HFS Plus, a 20-year-old filing system itself derived from Apple’s Hierarchical Filing System, or HFS, that dates back to the 1980s.

By some accounts, APFS was long overdue: HFS Plus dated from the early days of Mac OS, and wasn’t really designed for the Unix core that was introduced in OS X (now macOS).

For example, HFS Plus can’t deal with dates after 2040, and doesn’t allow multiple processes to access the filesystem at the same time, making it more sluggish and less future-proof than other widely-used filing systems such as NTFS on Windows and ext4 on Linux.

New drivers, new utilities

APFS was introduced as Apple’s default and preferred filing system in High Sierra.

This means new drivers inside the operating system to support disks formatted with the new system, and new features in Apple’s disk management utilities to prepare APFS disk volumes for use.

There are two main disk management tools in macOS – the easy-to-use graphical tool Disk Utility, and the super-powerful but arcane command line program diskutil.

It turns out that the APFS support in the High Sierra version of Disk Utility has feet of clay, as we’ll show here.

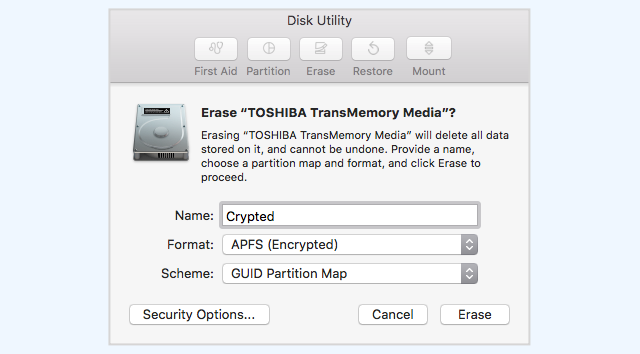

- We erased a USB disk and created a new

APFS (Encrypted)volume on it.

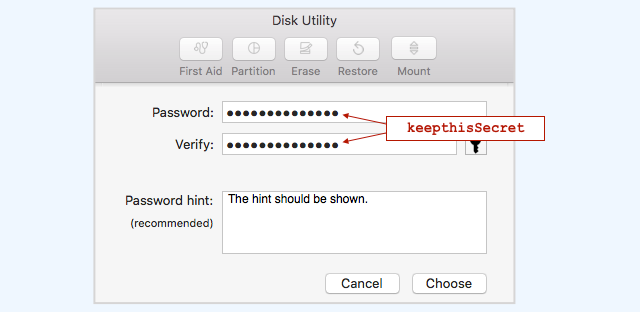

- Disk Utility prompted us for a password (twice) and an optional hint.

- We entered

keepthisSecretas the password andThe hint should be shownas the hint.

- Disk Utility created the encrypted volume and mounted it automatically.

- We unplugged the USB disk and then plugged it back in, and macOS asked for the password.

- We entered

keepthisSecretand the disk was unlocked and mounted, showing that the password had been set as expected.

So far, so good, until we unplugged the device and plugged it back in:

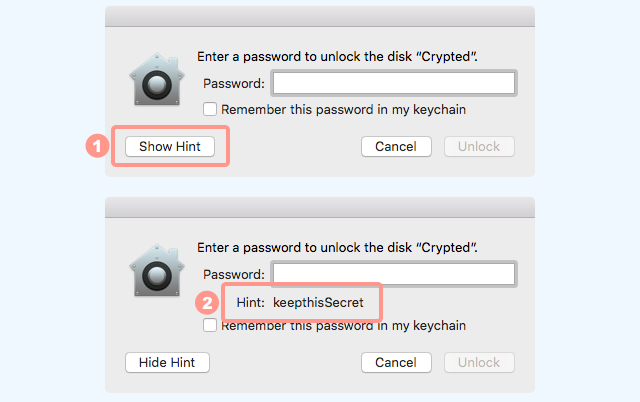

- Again, macOS asked for the password.

- This time, we clicked the

[Show Hint]button before entering the password. - The password dialog revealed that

keepthisSecrethas been set as the hint as well as the password.

The text The hint should be shown had, it seemed, simply been thrown away.

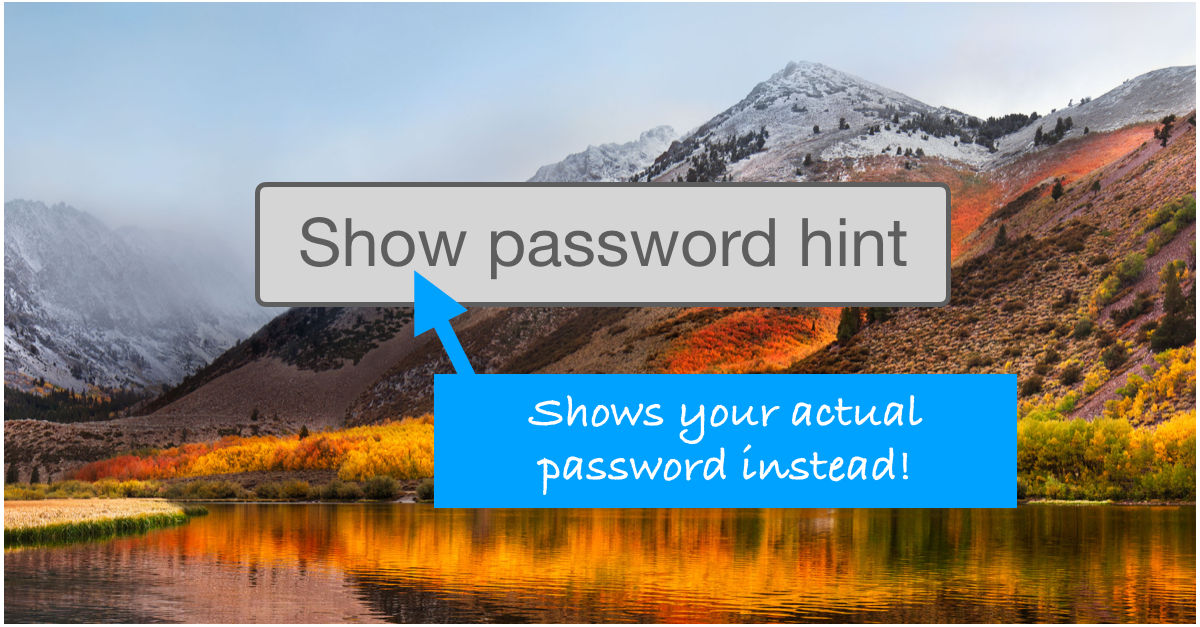

In other words, if you set a password hint as suggested, anyone who stole your disk could “hack” the password simply by using Disk Utility’s [Show Hint] button!

What to do?

- If you haven’t created any new APFS encrypted volumes since upgrading to High Sierra, you are OK.

- If you created an APFS encrypted volume but didn’t specify a hint, you are OK.

- If you created an APFS encrypted volume using

diskutilyou are OK (the bug is in Disk Utility, not the operating system itself). - If you upgraded to High Sierra from an earlier version of macOS, your disk will have been converted to APFS, but any hint you had before is left untouched (so far as we can tell), so you are OK.

- Apply the APPLE-SA-2017-10-05-1 Supplemental Update as soon as you can.

By the way, you can blank out the password hint on any APFS volume, just in case, with the following diskutil command in a terminal window:

$ diskutil apfs hint /Volumes/[YOURNAME] -user disk -clear Removing any hint from cryptographic user XXXXXXXX on APFS Volume diskYsZ $

If there wasn’t a hint, no harm is done, but you’ll see an error message like this, so by repeating the above command until you provoke the error message, you can verify that any hint was indeed scrubbed:

Error editing cryptographic user on APFS Volume: Unable to set APFS crypto user passphrase hint (-69554)

Alternatively, you can overwrite the existing password hint by using the command line option -hint, instead of -clear, like this:

$ diskutil apfs hint /Volumes/[YOURNAME] -user disk -hint "Your hint here" Setting hint "Your hint here" for cryptographic user XXXXXXXX on APFS Volume diskYsZ $

Whatever you do, though, don’t follow the suggestions of Apple’s own diskutil help text, which offers this terrible advice:

$ diskutil apfs hint help [. . . .] Set a passphrase hint for an existing cryptographic user; you can specify "disk" for the "Disk" user. Specifying "-clear" will remove any hint. Ownership of the affected disks is required. Example: diskutil apfs setPassphraseHint disk5s1 -user disk -hint NameOfMyPet $

Pets’ names makes a dreadful passwords, because they’re usually neither secret nor hard to guess, and setting a hint to tell a crook that you have made a dreadful password choice just makes a bad thing worse.

Of course, if you had set a hint with Disk Utility, then for all you know someone who knew the [Show Hint] trick might have seen your password, so you ought to change it.

You can update the passphrase on an APFS Encrypted volume quickly and easily as follows:

$ diskutil apfs changepassphrase /Volumes/[YOURNAME] -user disk Old passphrase for user XXXXXXXX: .......... New passphrase: .......... Repeat new passphrase: .......... Changing passphrase for cryptographic user XXXXXXXX on APFS Volume diskYsZ Passphrase changed successfully $

A bad look for Apple, letting a buggy system utility like that into a production release…

…but a creditable response by Apple in getting a fix out quickly.

FreedomISaMYTH

wow… no words.

Michael

Third bulleted item in What to do has F and P transposed.

Mark Stockley

Fixed, thanks!

James

To be fair, neither of the two people in the QA department use disk encryption.

Wilderness

Facepalm!

Marvin

Another spectacular failure for security demonstrating what gets missed when these companies insist on keeping everything closed source. If OSX was open source and went through a public development cycle, this would have been caught wat before release. So long as OSX is closed source, it will never be as secure as Linux.

Mark Stockley

Kees Cook, a researcher at Google, actually decided to find out how long bugs go undiscovered in the Linux kernel. He looked at over 500 bugs – the two bugs marked Critical took two years and five years to close, the 34 bugs marked High Severity had a mean average close time of six years.

Outside of Linux it’s no different. The ShellShock vulnerability in Bash went unnoticed between 1989 and 2014. The Heartbleed vulnerability in OpenSSL went unnoticed for two years.

Mozilla’s Secure Open Source initiative, which funds professional security audits of open source tools, exists precisely because open source tools can harbour serious vulnerabilities.

All of which is to say that the open source community itself has moved beyond the old trope that open source code is somehow inherently secure – that “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”. It simply doesn’t apply in the real world, not in quiet projects like OpenSSL nor in busy ones like Linux.

I am a huge fan of open source and in many ways I owe my entire career to it. It has many virtues but magical security is not one of them.

Paul Ducklin

What Mark said.

(“There’s no such thing as security pixie dust.”)

We discussed Kees Cook’s research here, including a graphic to help you visualise his findings:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2016/10/19/linux-kernel-bugs-we-add-them-in-and-then-take-years-to-get-them-out/

Paul Ducklin

You need some evidence for that claim, but I don’t think you’ll find it.

The aphorism that “with many eyes all bugs are shallow” has been shattered many times – the mere presence of many eyes is not enough; at least some of them need to be looking in the right direction, with the right motivation. Indeed, Naked Security has written many times about open source projects that have harboured eye-watering bugs for years, sometimes for more than a decade.

For a scholarly discussion of open-source versus closed-source security, written by well-known cryptographer Ross Anderson, you might like to read this paper:

https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/Papers/toulousebook.pdf

Larry Marks

Security and memory leaks! Nobody wants to work on them. There’s no glory in it. Remember Firefox? Everyone wanted to add his own pet feature. No one wanted to work on the memory leaks. Things finally got so bad that the admins had to direct that no features could be added until the memory leaks were fixed. Security works the same way.