Our researchers are currently seeing localized outbreaks of a new variant of the PlugX USB worm – in locations nearly halfway around the world from each other. After first drawing attention to itself in Papua New Guinea in August 2022, the new variant appeared in January both in the Pacific Rim nation and 10,000 miles away in Ghana. Additional infections appeared in Mongolia, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria. The novel aspects of this variant are a new payload and callbacks to a C2 server previously thought to be only tenuously related to this worm.

Figure 1: An unusual distribution of infections is the hallmark of a new PlugX variant that relies on DLL sideloading to propagate

Everything Old Is New Again

PlugX is fairly common backdoor malware (a RAT, remote access Trojan) of Chinese origin, one that relies on DLL sideloading to do its dirty work. We at Sophos have been writing about it for years, most recently in November. Even the USB-aware version, which can both spread via USB and grab information from air-gapped networks via USB, has been on defenders’ radar for several years. However, new variants have turned up regularly in recent months, sometimes in remarkably far-flung locations.

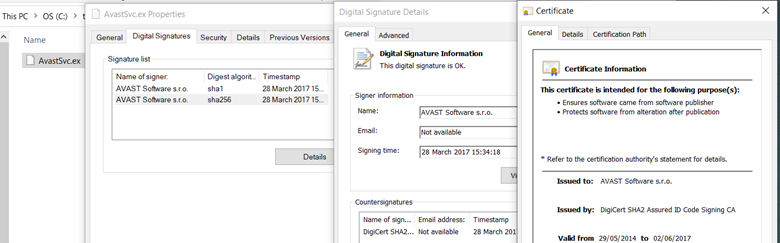

Our first look at the new variant of the worm came from a CryptoGuard alert likely triggered by data exfiltration. (We’ve put all IoCs for this incident on our GitHub instance.) The infection comprises a clean executable (AvastSvc.exe) susceptible to DLL sideloading; multiple instances of a malicious DLL (wsc.dll) sideloaded into the clean loader; an encrypted .dat payload; and (in a directory called RECYCLER.BIN) a collection of stolen, encrypted files with names obfuscated in base64:

Mitigation CryptoGuard V5 Path: C:\ProgramData\AvastSvcpCP\AvastSvc.exe (clean Avast app) Hash: 85ca20eeec3400c68a62639a01928a5dab824d2eadf589e5cbfe5a2bc41d9654

In our detailed behavioral log for the incident, we noted the following:

Command line: RECYCLER.BIN\1\CEFHelper.exe 142 60 SHA1: 049813b955db1dd90952657ae2bd34250153563e SHA256: 85ca20eeec3400c68a62639a01928a5dab824d2eadf589e5cbfe5a2bc41d9654

“CEFHelper” is the name of an Adobe process, but that’s not what this file is – as shown by comparing this SHA256 hash to the hash shown in our previous code snippet (just above Figure 2) for the subverted clean executable, they’re the same file, renamed by the malware. When the file executes, the AvastSvc executable is once again visible:

"commandLine" : "C:\\ProgramData\\AvastSvcpCP\\AvastSvc.exe 983", "commandLine" : "C:\\Windows\\system32\\cmd.exe /c D:\\RECYCLER.BIN\\143CE844B89AC3D0\\tmp.bat", "commandLine" : "arp -a ", "commandLine" : "ipconfig /all ", "commandLine" : "systeminfo ", "commandLine" : "tasklist /v ", "commandLine" : "netstat -ano ",

A Funky Five

We saw five file names associated with the infection at this stage. In order, these are the information that the worm collects, the batch file that actually collects the information, and three sideloading components:

"path" : "d:\\recycler.bin\\143ce844b89ac3d0\\c3lzlmluzm8", "path" : "d:\\recycler.bin\\143ce844b89ac3d0\\tmp.bat", "path" : "d:\\recycler.bin\\1\\avastauth.dat" "path" : "d:\\recycler.bin\\1\\cefhelper.exe", "path" : "d:\\recycler.bin\\1\\wsc.dll",

We’ll discuss those files at greater length momentarily. We saw three hashes – or, since the cefhelper.exe and avastsvc.exe file are the same file and have identical hashes, one could say we saw two hashes and one doppelgänger:

d:\recycler.bin\1\cefhelper.exe : 85ca20eeec3400c68a62639a01928a5dab824d2eadf589e5cbfe5a2bc41d9654 c:\programdata\avastsvcpcp\avastsvc.exe : 85ca20eeec3400c68a62639a01928a5dab824d2eadf589e5cbfe5a2bc41d9654 c:\programdata\avastsvcpcp\wsc.dll : 352fb4985fdd150d251ff9e20ca14023eab4f2888e481cbd8370c4ed40cfbb9a

Shady Mustang, Revealed Panda?

We then saw C2 activity reaching out to multiple variations on the IP address 45.142.166[.]112. This IP address was mentioned in in a 2019 Unit 42 blog post as “other PlugX,” not at that point tied directly to PKPLUG (aka Mustang Panda), the threat actor associated most closely with this malware. At the time, Unit 42’s researchers described this finding as a RAT previously seen post-exploitation in an unrelated infection. Our analysis indicates that all methods seen in use during our investigation align with what is known about the PKPLUG / Mustang Panda actor, thus strengthening the link between this IP address and the threat actor.

The compressed parent as seen on VirusTotal:

e07d58a12ceb3fde8bb6644b467c0a111b8d8b079b33768e4f1f4170e875bc00: AvastSvcpCP(2).zip

The contents of that file when unzipped look familiar:

432a07eb49473fa8c71d50ccaf2bc980b692d458ec4aaedd52d739cb377f3428 *AvastAuth.dat 85ca20eeec3400c68a62639a01928a5dab824d2eadf589e5cbfe5a2bc41d9654 *AvastSvc.exe e8f55d0f327fd1d5f26428b890ef7fe878e135d494acda24ef01c695a2e9136d *wsc.dll

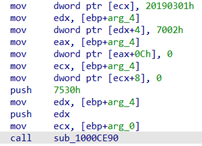

The payload is PlugX. This version of the payload is called 20190301h:

Config data: Installation directory: AvastSvcpCP Mutex name: cUUEdKgjnOOOrpkUEjHp C2 server: 45.142.166[.]112

This PlugX malware has a long history and has been dissected in other industry writeups, such as Avira’s and QiAnXin’s analyses. In this coverage we’ll mainly focus on the USB worm functionality.

It uses mutex when copying files to available removable media, using these template strings:

USB_NOTIFY_COP_%ws USB_NOTIFY_INF_%ws

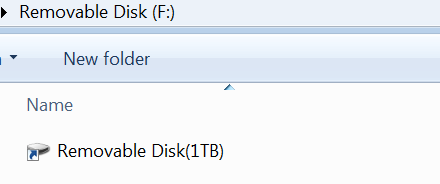

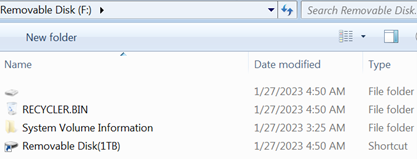

It then uses a couple of tricks to hide its malicious content from the casual observer. First, the infected removable media will seem to be empty. In Windows Explorer it would appear that the drive only contains another removable drive.

Figure 3: A suspiciously tidy view from inside Explorer

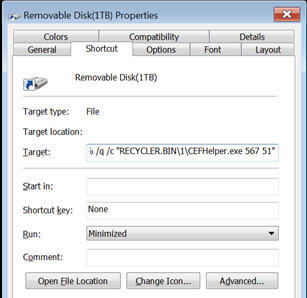

In reality the displayed item is not actually a drive but a Windows shortcut file, using an icon resembling the one used for removable media. Should the victim click on this file, it runs the CEFHelper executable we noted above:

Figure 4: The “removable disk” is revealed as the questionable CEFHelper executable

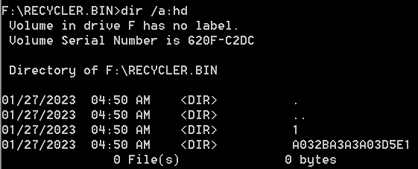

The other files and directories have the hidden and system attributes set, so they will not be visible by default in the file listing. After specifically enabling the display of hidden and system files, we can see the rest of the content (and also see the “Removable Disk(1 TB) item correctly shown as a mere shortcut):

Figure 5: With display enabled for hidden and system files, the “tidy” view in Figure 4 changes

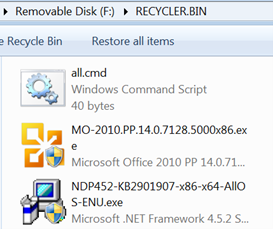

The files copied by the backdoor are in the RECYCLER.BIN directory – for which the worm, in another obfuscation maneuver, drops a desktop.ini file that associates the directory with the actual Recycle function. (RECYCLER is the NTFS-era name for the thing that is $Recycle.bin on modern Windows systems; NTFS systems include Windows 2000, NT, and XP.) This causes Windows to treat the directory as if it really is a Windows Recycle Bin, and files deleted by the user will be displayed there – not even those from the USB drive, but from the user’s actual hard drive.

Figure 6: Contents of the system’s actual trash, displayed in “recycler.bin”

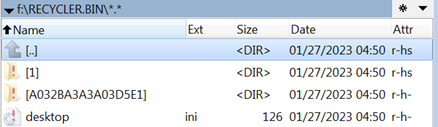

Again, specific commands in the Windows command prompt reveal the real content of the RECYCLER.BIN directory:

Figure 7: Once again, hidden files are revealed

Alternatively, a less easily deceived file explorer, such as Total Commander, can be used to browse the content. Both methods show that the RECYCLER.BIN directory actually contains two subdirectories:

Figure 8: The same directory viewed through Total Commander

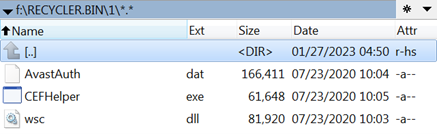

The directory named 1 contains the DLL sideloading components we’ve previously seen:

Figure 9: Delving into the directory called 1

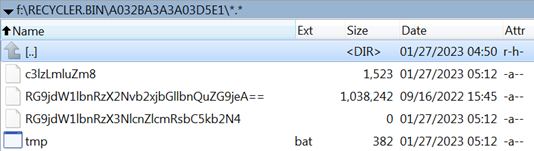

The other directory, which has a random name, contains the victim’s exfiltrated files. The first image below is the intermediate state. Note the tmp.bat file present:

Figure 10: The other directory, where the victim’s belongings are stashed

The tmp.bat file collects the system info and saves it to the first seemingly randomly named file in the directory shown above (in the image, the file that’s over 1GB in size). That file name is not truly random – it is the base64 encoded form of sys.info.

When the batch file has finished its collection, it removes itself. All that’s left are the “c3lzLmluZm8” file with the system info and the collected files.

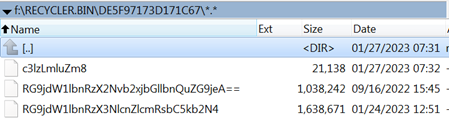

Figure 11: The other directory once more, after the batch file has finished its dirty work and removed itself

PlugX collects .doc, .docx, .xls, .xlsx, .ppt, .pptx and .pdf files (if the individual file size is not larger than 314572800 bytes), likely for exfiltration. It saves them in encrypted form to the RECYCLER.BIN as shown above. The filenames, including the path indicator, are converted to base64 form. For example, in the Figure 11 image, the two file names decode to:

Documents_coolclient.docx Documents_serverdll.docx

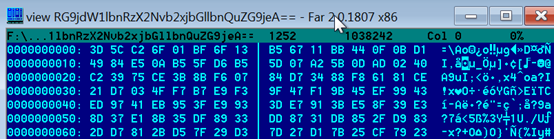

The content of each file is also, of course, encrypted:

Figure 12: The victim’s belongings, encrypted

As noted above, Sophos detected and blocked the attempted exfiltration. We’ll add the IoCs discussed in this thread to our Github repository.

As for the use of USB worms in 2023, they were certainly more common a decade or two ago, when a threat actor could compromise the Pentagon by dropping a thumb drive or two in the right parking lot. However, as defenders alerted users to the potential attack vector, and other method of file storage and transmission became more popular, this technique was abandoned. Now APT groups are re-adding this method as an effective infection and exfiltration method. Once again an old technique resurfaces and makes new waves — this time causing far-flung local outbreaks.

Simon

Can we get a direct link to the Indicators of Compromise? The GitHub repository does NOT make it obvious which file corresponds with THIS article, and the last modification was 3 weeks ago.

Angela Gunn

Hi Simon — you’re right — a better link would help. Added that in. Thanks for saying something!

K505

What happens to the data on the infected portable disk? Would day be any percentage to recover? Thanks for sharing.

Angela Gunn

Hi there — the good news is that whatever other data you have on the USB drive isn’t directly affected by the worm; the worm simply places an encrypted copy of the original documents from the hard drive on the USB. The documents remain in place on the hard drive — they are not lost, so it makes little sense to decrypt the copies from the USB. (Goes without saying that you should handle an infected USB drive with utmost care and isolation, and that touching the encrypted file, which may or may not contain material exfiltrated from elsewhere, is just not a good idea.) Hope that helps.