In the past few days, both Apple and Adobe have published software updates to close off zero-day security holes that were already being exploited by attackers.

Remember that a zero-day exploit is a security bypass (typically, one that allows Bad Guys to break in and run or implant software of their own choosing) that was discovered and abused by the attackers before the Good Guys found and fixed it.

In other words, no matter how quickly you update against a zero-day once the patch is announced, you know that someone – and you have to hope that it wasn’t you! – has already been attacked and pwned, even if they’re accustomed to patching promptly themselves.

Loosely put, the zero part of the jargon reminds you that there were zero days during which you could have been patched proactively, no matter how hard you tried, because the attackers got there first.

Annoyingly, but perhaps understandingly, both Apple and Adobe made only the briefest of admissions about the zero-days they fixed.

Apple said simply that it was “aware of a report that [CVE-2022-22620] may have been actively exploited”:

Abobe was slighly more forthcoming, admitting that it was “aware that CVE-2022-24086 has been exploited in the wild in very limited attacks”:

No hints about how or where the attacks were carried out, what the attackers were after, what the attackers made off with, what indicators of compromise (IoC) you could look for in your own logs, how to evalualate your risk, or whether there are any workarounds or mitigations you could apply until you’re sure everything’s been patched.

Now it’s Google’s turn to wave its hand at a just-patched zero-day bug: the company has pushed out the latest Chrome update, using an underwhelmingly Apple-esque remark that it is “aware of reports that an exploit for CVE-2022-0609 exists in the wild”.

Use-after-free bugs galore

Intriguingly, CVE-2022-0609 was only one of five use-after-free coding bugs fixed in this update.

A use-after-free bug happens when one part of a program requests a block of memory to be reserved for its own exclusive access, uses that memory for a while, then relinquishes its claim on that memory block…

…only to carry on accessing that memory anyway, even after it’s been reallocated to some other part of the program, or perhaps even to another program entirely.

Imagine that you’re in the middle of a PowerPoint presentation that you’ve checked carefully and rehearsed plentifully, but just before you click through from slide 4 to slide 5, someone who thinks they’re updating slide 5 of their presentation manages to write their new data into your presentation instead. You’d end up blithely presenting someone else’s content as your own, with no inkling of the impending disaster. Even if that sort of thing happened entirely by accident, due to a genuine mistake by a trustworthy colleague, the outcome would probably be annoying, and might even be embarrassing. But if the other person knew perfectly well what they were doing, and how to orchestrate it, and if they timed their “intervention” deliberately and maliciously, the outcome could be disastrous, and perhaps even career limiting. That’s an analogy of the content crisis that use-after-free bugs can cause, often with malware implantation being the unexpected and unwanted side-effect of an exploitable use-after-free hole.

Why browser zero-days matter

Zero-days triggered by memory mismanagement while the browser is rendering a page are always worrying.

That’s because remote code execution (RCE) holes in a browser often lead to so-called drive-by downloads, where merely looking at a booby-trapped web page could leave you with malware implanted on your computer or your phone.

You will also hear this sort of infection called a zero-click attack, because the attackers don’t need to convince you (or your computer) to do anything more than to view their content – something that’s generally supposed to be safe because it happens entirely inside your browser window.

Most phishing attacks, for example, need to persuade you to fill in and submit a dishonest web form, to open a malicious attachment, or to agree to download and launch a file you weren’t expecting and didn’t ask for.

That gives well-informed users a good chance to avoid the attack, because it generally can’t happen by default, or by mistake.

But a zero-click or drive-by attack can happen “by default”, without giving even the best-equipped user a chance to to say, “No!” and head off the malevolence.

What to do?

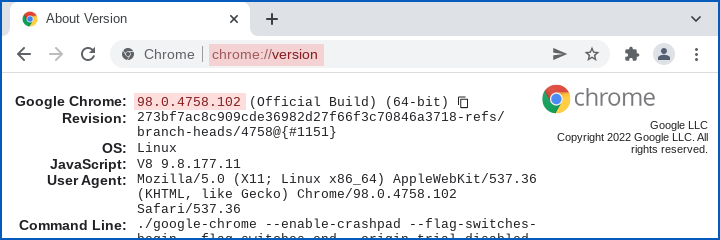

Check that you have Chrome (or Chromium) 98.0.4758.102 or later, up from the previous official build number of 98.0.4758.80.

You can list the version number by visiting the special URL chrome://version in your Chrome (or Chromium-based) browser: the four-part version number should appear on the first line of the output, like this:

We can’t tell you whether Edge, probably the next-most-widely-used Chromium-based browser out there, is affected by this bug, and Edge version numbers don’t align with Chrome’s numbering after the initial pair of “major/minor” numbers (in this case, 98.0).

The stable version of Edge doesn’t have an update out yet [2022-02-15T16:10Z], at least in its official Linux repository, where we update from, but we suspect there will be one out soon.

To check whether you’re already running the latest version in both Chrome and Edge, click DotDotDot (the More menu) in the top right, then use Help and About to access the version-plus-update dialog.

Update. The Edge repository linked to above was updated on 2022-02-16 with Edge 98.0.1108.55. The URL edge://version (or, for that matter, chrome://version) will report the four-part version number you’re using.

Spike Robinson

No update yet on Google Play for the Android version of Chrome. Last update is in January.

Raylund

It should be populated now. My phone updating now and Google Play on their website too which dated at February 14, 2022

Paul Ducklin

My Google Play just updated me to a version listed as “updated on 14 Feb 2022” (which sounds right) but gives the Chrome version as 98.0.4758.101. Higher than the .80 I listed above, but not quite the .102 that’s in Google’s advisory for the Desktop version.

So there was a very recent Chrome for Android update waiting for me in Google Play… but the number doesn’t match what I’d *like* to see, and there isn’t any obvious release notes page for the Android version that says whether .101 fixes CVE-2022-0609 (or indeed any of the other vulns) listed in the Desktop advisory.

I *suspect* I am patched (or at least “patched enough”) but overall the situtation is clear as mud :-(

Raylund

Here’re 2 links from chromium src:

98.0.4758.87..98.0.4758.101, https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+log/98.0.4758.87..98.0.4758.101?pretty=fuller&n=10000

98.0.4758.80..98.0.4758.102, https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+log/98.0.4758.80..98.0.4758.102?pretty=fuller&n=10000

If the zero-day fix is this one:

https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/e3805f29fed78bac51e5ee5315719a4208f1ff10

Then it’s in the 102 (desktop) and 101 (Android) versions

I cannot tell as I don’t understand the details (they don’t reference to CVE)

Paul Ducklin

I glanced at that patch and it looks more like a race condition fix (event ordering) than the sort of changes you’d expect in a use-after-free fix. (There’s no mention in the comments that the event re-ordering has anything to do with memory management issues elsewhere.)

Kyle

I have noticed this very frequently with other apps, too. It’s like Google Play fails to refresh. Meanwhile the vendor insists “Yes, we have published the latest version 4 hours ago already.” It’s frustrating, and I’ve started using alternative app stores as a result.

MarkyMark

Chrome on my Android device is still running 98.0.4758.101 with no update from Google Play. 12:55 a.m. EST.

Kyle

Do we know what the exploit actually does? I’m going to start getting very cynical if every other zero-day is now RCE.

Paul Ducklin

That’s the underlying theme of this article…

…no, we don’t know what the exploit actually does. We don’t even have Google, who seem to demand speed and clarity from other vendors via Project Zero revelations, admitting anything more than “we’ve seen reports that people have seen this out there”. (One assumes that Google believes those reports, and has made some attempt to establish their veracity. But, like Apple, there’s still a veneer of ‘it might just be rumours’ deniability in the official comment. At least Adobe used the words “aware of exploits”, rather than just “aware of reports of exploits”.)

As I wrote above, this business of saying “we’ve heard rumours of exploits” (and nothing more) gives you: no hints about how or where the attacks were carried out, what the attackers were after, what the attackers made off with, what indicators of compromise (IoC) you could look for in your own logs, how to evalualate your risk, or whether there are any workarounds or mitigations you could apply until you’re sure everything’s been patched.

As for assumiung that anything dubbed “0-day” implies RCE – I think that’s a wise approach, not a cynical one! One thing I like about Mozilla’s security bulletins is the bit where they have a generic section for memory mismanagement bugs that were found and patched, and admit/assume that “these could be made exploitable given enough effort”, or words to that effect.

Mike Eisen

Thanks for the heads up. My Chrome browsers just updated to the latest version.

Scott W.

A zero-day vulnerability is not necessarily exploited yet, it simply means it is known and not patched. Many vulnerabilities are discovered by researchers who can contact the software manufacturer, file a CVE or both. If they file a CVE before a patch is available, it is a zero-day vuln. It used to be that telling a company would involve some negotiation about who gets to announce it. The finder wants credit.

Typically the CVE will not contain any useful info which is frustrating but necessary to not tell the world how to exploit it.

Paul Ducklin

I think it’s generally accepted – indeed, I would call it a matter of definition – that calling a bug a “zero-day” implies not only that the bug is already known to attackers, but also that those attackers know how to exploit it to do unauthorised stuff.

Responsibly disclosed bugs – where the bug-finder tells the vendor privately and gives them a fair time to fix it before disclosing the details publicly – are not zero-days. So, the fact that a CVE is assigned before a patch is out does not make it a zero-day. (In fact, today’s CVE entries almost always say little more than “this item is reserved for future disclosure” until the pre-agreed disclosure date arrives. In any case, many, if not most, CVEs these days are assigned directly by vendors from pre-allocated batches of numbers as soon the details of the bug are confirmed.

Google patched at least eight CVE-numbered bugs in the latest Chrome update. Only one of them (the bug described here) is considered a “zero-day”, because all the others were patched *before* their details became known beyond Google and the people who found them, and were therefore not being exploited in the wild before the patch arrived.

Diane MP

What’s the casual, mildly proficient user supposed to do? Checking my Chrome version gives me a number that does not resemble the required one. On GPlay I just get “already installed.”

If experts can’t figure out the complexities of this threat and how to protect against it…well, maybe it’s time for people like me to just move on from the computer era. I-ve been wanting to start painting again, anyway, and my phone works just fine independent of…you know…the internet.

Paul Ducklin

What ydo you get if you type the URL “chrome://version” in the address bar of your browser (that’s a special internal page)?

The first line of output should say something like “Chrome: 98.0.XXXX.YYY”, where XXXX.YYY are supposed to be 4758.102 at the moment [2022-02-16T11:40Z].

That special URL also works on Android. As mentioned above, mine currently says “98.0.4758.101” on Android, although the date the update was published was 14 Feb 2022.

I agree with you that, despite the protestations of companies including Google that we need to get better and faster at updates, it can be surprisingly hard to figure out whether you are truly up to date. (By that I mean that it is often easy to verify you *are* on the expected version… but if you aren’t, or you don’t seem to be, how bad is that? what does it mean? Is the “.101” version on my phone good enough, or am I missing the one patch I really need? Also, despite Google’s zeal in telling other vendors to put out patches promptly and urging all users to get updates as quickly as they can, the company still to its own Chrome security bulletins to tell us that updates “will roll out over the coming days/weeks”. There’s an exploitable hole being used by Bad Actors right now, and it might be *weeks* before the update rolls out to me? Surely some mistake…)

Paul Ducklin

for clarity, I added a screenshot of Chrome at the “chrome://version” screen to the article. HtH.

Anonymous Coward

Great article.

Typo at:

“Abobe was slighly more forthcoming, **admitteding** that it was…”.

Cheers.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks!

Typo fixed…