Eight years ago, security researcher Colin Mulliner found and reported an intriguing bug to Apple.

Even though the bug was in Safari on iOS, the vulnerability involved unwanted telephone calls, thanks to a special sort of web link using URLs starting with tel:.

Here’s how it worked.

Web pages are typically full of HTML links specified something like this:

<A HREF="https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/">Read Naked Security</A>

A and /A denote the start and end of an Anchor, which makes the enclosed text into a link.

HREF stands for Hypertext REFerence, which is the fancy name for a clickable link to some other resource.

The https:// prefix in the link itself means to use the HTTPS protocol to fetch the content of the link via the web.

But you can also have a link like this:

<A HREF="tel:+441632960042">Call now</A>

This time, the clickable link uses the tel: prefix to specify a phone number to dial, assuming that the device on which you are browsing is capable of making calls.

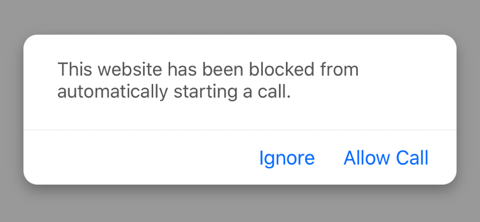

In mobile Safari, for example, clicking the Call now link above typically produces a popup like this, at least the first time you try to dial the number:

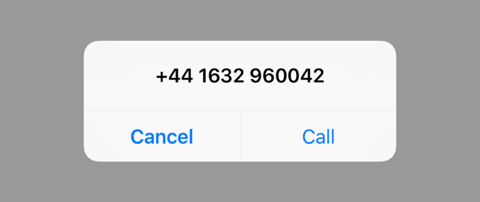

If you choose to allow the call, you’ll see a confirmation dialog like this, asking if you actually want to place the call:

The UK phone number above looks realistic but is one of a range specifically reserved for use in TV and radio programmes, and other uses such as this one. You won’t annoy anyone if you call it because it is deliberately unallocated. If you need phone numbers for your own documentation, try to find your country’s “official made up numbers” range. Don’t risk picking someone’s real number by mistake.

Back in 2008, Mulliner found that there were other ways of introducing a tel: link to Safari that would jump over the warning dialogs, pop up the phone app automatically and dial the number without asking.

The tricks discovered by Mulliner included placing a telephone URL in an IFRAME, using a phone number as the target of a web page refresh or redirect, and altering the URL of an already-loaded page using JavaScript.

When he morphed an already-requested page that wasn’t a tel: link into one that was, he could autodial a number of his choice.

If you didn’t notice the phone app starting to dial, then there was a good chance that the call woud go through unintentionally.

An unwanted call to a friend would be annoying, probably to both parties; a call to a pay-by-the-minute premium rate number owned by a crook would be costly; and an unwanted emergency call would be downright dangerous.

Apple fixed the bug and Mulliner then disclosed it responsibly.

Incidentally, he also found a way to trigger the bug while at the same time tying up the iPhone’s Messaging app in the time-wasting task of trying to send a text message to a bogus but enormously long phone number.

In this case, he discovered that the phone app had enough processor power left over to place the call, but not enough responsiveness to let you cancel the call immediately.

That made the bug even more severe, because crooks who were determined to cost you money via a phoney premium line might be able to get through and rack up their fees before you had a chance to cut off the call.

Eight years after

Fast forward to 2016, and Mulliner happened to notice a story in the media about an American youngster arrested for allegedly promoting a website containing a link that ultimately initiated anywhere from hundreds to thousands of bogus 911 calls (the US emergency number), all from iPhones.

Naturally, Mulliner wondered, “Could this be my 2008 bug all over again?”

Unfortunately, he discovered that the answer is, “Probably, though in a slightly different form.”

That’s because iOS includes a sort-of “minibrowser” that App Store apps can use to display HTML content without switching you across into the full-blown Safari app.

The minibrowser component is known as WebView, and apps use it for a variety of purposes, from displaying licence agreements and bringing up help screens to letting you preview web links while keeping you inside the original app.

(If you click out of a dedicated app into full-screen Safari, there’s always a chance that you’ll carry on browsing in Safari, so the vendor of the original app won’t get you and your revenue-generating potential back.)

And, according to Mulliner, his old proof-of-concept code still works, more or less, when it’s loaded inside a variety of WebView-enabled iOS apps.

In short, it looks as though the fixes that Apple put into the Safari source code all those years ago never made it into the related code in the WebView minibrowser.

What to do?

Mulliner has reported this problem to Apple, so a fix in the WebView component itself will probably show up in a forthcoming iOS update.

In the meantime:

- App developers who use WebView can add code to detect and prohibit the use of

tel:links in the content they display.

As the name suggests, WebView is intended specifically for viewing web content, so blocking the presence of tel: links is unlikely to hamper the functionality of the app.

- When clicking links in dedicated apps such as Twitter, Facebook and the like, keep your eye out for the unexpected appearance of the iOS phone app.

If it pops up uninvited, you may have activated a tel: link by mistake.

Don’t panic: even if crooks use Mulliner’s trick to slow down access to kill the call for a second or two, they can’t keep you out indefinitely.