Cybersecurity stories are like buses: the one you’re waiting for doesn’t come along for ages, then two arrive at once.

The specialist subject that suddenly popped up twice this week is: resonance.

On Monday, we wrote about Janet Jackson’s 1989 song Rhythm Nation, and how it inadvertently turned into a proof-of-concept for a Windows-crashing exploit that was reported way back in 2005.

That story was publicised only recently, as a bit of weird historical fun, and with an equal sense of fun, MITRE assigned it an official CVE bug number (confusingly, however, with a 2022 datestamp, because that’s when it first became known).

In that “exploit”, something about the beat and mix of frequencies in the song is alleged to have troubled the disk drives in a certain vendor’s Windows laptops, matching the natural vibrational frequencies of the old-school hard disks…

…to the point that the resonance effects produced enough vibration to crash the disk, which crashed the driver, which crashed Windows.

Apparently, even nearby laptops with the same model of disk could be R&Bed to the point of failure, bringing down the operating system remotely.

The solution, apparently, involved adding some sort of band-pass filter (band as in “range of frequencies”, not as in “group of musicians”) that chopped out the resonance and the overload, but left the sound well-defined enough to sound normal.

Two buses at once

Well, guess what?

At around the same time that the Rhythm Nation story broke, a researcher at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel published a research paper about resonance problems in mobile phone gyroscopes.

Modern phone gyroscopes don’t have spinning flywheels housed in gimbals, like the balancing gyroscope toys you may have seen or even owned as a youngster, but are based on etched silicon nanostructures that detect motion and movement through the earth’s magnetic field.

Mordechai Guri’s paper is entitled GAIROSCOPE: Injecting Data from Air-Gapped Computers to Nearby Gyroscopes, and the title pretty much summarises the story.

By the way, if you’re wondering why the keywords Ben-Gurion University and airgap ring a bell, it’s because academics there routinely have absurd amounts of fun are regular contributors to the field of how to manage data leakage into and out of secure areas.

Maintaining an airgap

So-called airgapped networks are commonly used for tasks such as developing anti-malware software, researching cybersecurity exploits, handling secret or confidential documents safely, and keeping nuclear research facilities free from outside interference.

The name means literally what it says: there’s no physical connection between the two parts of the network.

So, if you optimistically assume that alternative networking hardware such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth are properly controlled, data can only move between “inside” and “outside” in a way that requires active human intervention, and therefore can be robustly regulated, monitored, supervised, signed off, logged, and so on.

But what about a corrupt insider who wants to break the rules and steal protected data in a way that their own managers and security team are unlikely to spot?

Ben-Gurion University researchers have come up with many weird but workable data exfiltration tricks over the years, along with techniques for detecting and preventing them, often giving them really funky names…

…such as LANTENNA, where innocent-looking network packets on the wires connecting up the trusted side of the network actually produce faint radio waves that can be detected by a collaborator outside the secure lab with an antenna-equipped USB dongle and a software defined radio receiver:

Or fan speeds used to sent covert sound signals, in a trick dubbed the FANSMITTER:

Or using capacitors on a motherboard to act as tiny stand-in speakers in a computer with its own loudspeaker deliberately removed.

Or adding meaning to the amound of red tint on the screen from second to second, and many other abstruse airbridging tricks.

The trouble with sound

Exfiltrating data via a loudspeaker is easy enough (computer modems and acoustic couplers were doing it more than 50 years ago), but there are two problems here: [1] the sounds themselves squawking out of speakers on the trusted side of an airgapped network are a bit of a giveaway, and [2] you need an undetected, unregulated microphone on the untrusted side of the network to pick up the noises and record them surreptitiously.

Problem [1] was overcome by the discovery that many if not most computer speakers can actally produce so-called ultrasonic sounds, with frequencies high enough (typically 17,000 hertz or above) that few, if any, humans can hear them.

At the same time, a typical mobile phone microphone can pick up ultrasonic sounds at the other side of the airgap, thus providing a covert audio channel.

But trick [2] was thwarted, at least in part, by the fact that most modern mobile phones or tablets have easily-verified configuration settings to control microphone use.

So, phones that are pre-rigged to violate “no recording devices allowed” policies can fairly easily be spotted by a supervisory check before they’re allowed into a secure area.

(In other words, there’s a real chance of being caught with a “live mic” if your phone is configured in an obviously non-compliant condition, which could result in getting arrested or worse.)

As you’ve figured from the title of Guri’s paper, however, it turns out that the gyroscope chip in most modern mobile phones – the chip that detects when you’ve turned the screen sideways or picked the device up – can be used as a very rudimentary microphone.

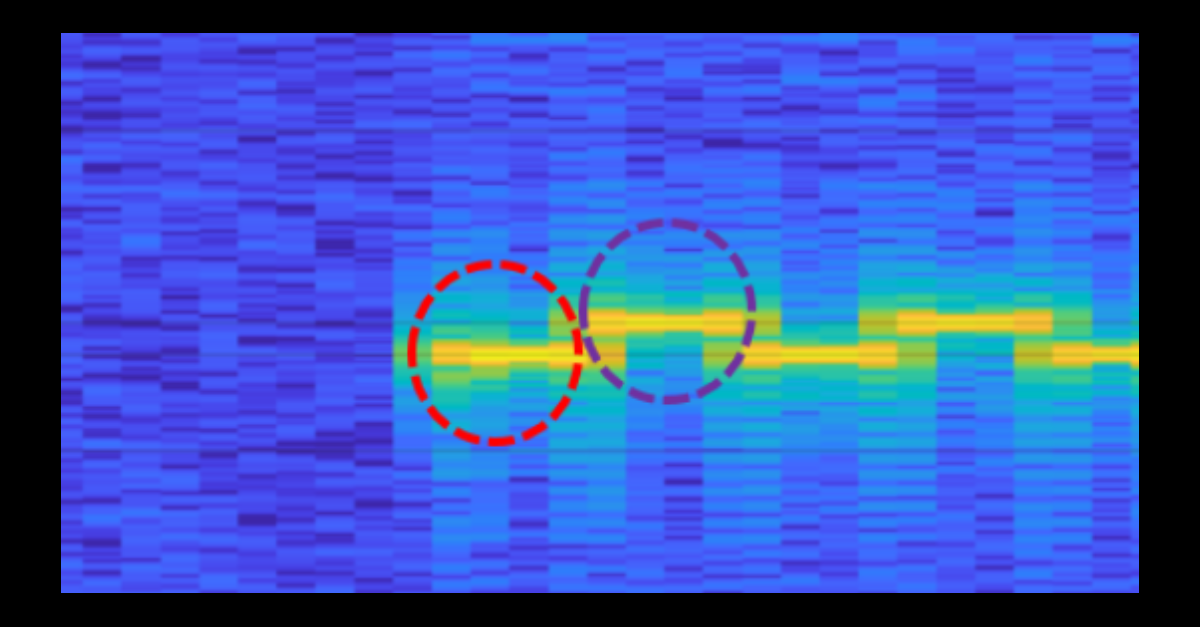

Greatly simplified, the GAIROSCOPE data exfiltration system involves exposing a known mobile phone to a range of ultrasonic frequencies (in Guri’s example, these were just above 19,000 hertz, too high for almost anyone on earth to hear) and finding out a precise frequency that provokes detectably abnormal resonance in the gyroscope chip.

Once you’ve found one or more resonant frequencies safely out of human hearing range, you’ve effectively got yourself both ends of a covert data signalling channel, based on frequencies that can inaudibly be generated at one end and reliably detected, without using a regular microphone, at the other.

The reason for targeting the gyroscope is that most mobile phones treat the gyroscope signal as uncontroversial from a privacy and security point of view, and allow apps (on Android, this even includes the Chrome browser) to read out the gyroscope X, Y and Z position readings by default, without any special permissions.

This means a mobile device that has apparently been configured into “no eavesdropping possible” mode could nevertheless be receiving secret, inaudible data via a covert audio channel.

Don’t get too excited about throughput, though.

Data rates generally seem to be about 1 bit per second, which makes 50-year-old computer modems seem fast…

…but data such as secret keys or passwords are often only a few hundred or a few thousand bits long, and even 1 bit/sec could be enough to leak them across an otherwise secure and healthy airgap in a few minutes or hours.

What to do?

The obvious “cure” for this sort of trick is to ban mobile phones entirely from your secure areas, a precaution that you should expect in the vicinity of any serious airgapped network.

In less-secure areas where airgaps are used, but mobile phones are nevertheless allowed (subject to specific verified settings) as an operational convenience, the invention of GAIROSCOPE changes the rules.

From now on, you will want to verify that users have turned off their “motion detection” system settings, in addition to blocking access to the microphone, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and other features already well-known for the data leakage risks they bring.

Lastly, if you’re really worried, you could disconnect internal speakers in any computers on the secure side of the network…

…or use an active frequency filter, just like that unnamed laptop vendor did to block the rogue Rhythm Nation signals in 2005.

(Guri’s paper shows a simple analog electrical circuit to cut off audio frequencies above a chosen value.)

Jack Wickwre

The Janet Jackson problem reminds me of the infamous ‘never position DEC disk drives North-South’ problem. This was from a combination of a unique physical layout and an activity schedule. Like the old story of a computer crashing at the same time, each day caused by an unwitting custodian unplugging it to plug in the floor buffer, this was a combination of an accident of building layout and coincidence.

In a computer lab in DEC’s mill complex, Building 5 hard drives were frequently crashing at about the same time on certain days of the week. The field service trouble-shooters were stymied. All the diagnostics were fruitless. Then while an FS tech was working on the system, it crashed! But the tech noticed that there had been a tremor when it happened. He went to a window and looking down, he saw a truck just being opened to make a delivery. He went to the dock and found that this was a regular delivery same times, same days. Since the loading dock was directly below the lab, the vibration of the truck hitting the dock bumpers was just strong enough to move the read-write head off track and cause a crash.

Now the interesting part, it so happened that the building was built with the long axis east-west and the drives were tidily lined up so that the arm of the read-write head was by coincidence oriented north-south. rotating the drives off their orientation solved the problem.

But here’s the fun part: when the service bulletin was issued, the north-south orientation was mentioned as an amusing point of interest. However, people’s memories being what they are the fact that these were magnetic drives and the fact that they were “magnetically” oriented was mixed together and an Urban Legend created that you shouldn’t position DEC north-south.

Haha

Someone is a bit paranoid

Paul Ducklin

I’ll let you do it for me… I didn’t mention it here because it’s a phone-only offering (it doesn’t work on desktops so it can’t form-fill laptop browser logins automatically, for example).

That makes it more of a phone password storage utility than a full-blown password manager.

Having said that, it’s self-contained inasmuch as the password database isn’t held in the cloud (unless you choose to copy it there)… it’s just a local, encrypted blob as described above.

Free for Androids and iDevices (see Google Play and App Store).

Anonymous

The article’s title states that the “phone’s compass” is being used as a microphone. However, it is the phone’s gyroscope that is used, not its magnetometer.

When I clicked on this article, I had already read about the gyroscope-based approach elsewhere and was expecting to learn about some new approach. Please fix the title.

Thank you!

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

I was under the impression that the compass used both gyroscopy (to decide when the phone was moving) and magnetometry (is that a word?) to detect its orientation.

I changed it. I also removed the exclamation point, which I decided I no longer liked (or needed, or wanted).

Terry

Hi, Paul. First time Naked Security reader, and thus first time commenter. This article came up in my Google News feed.

While the subject matter likely will have nearly zero impact on my personal life, I still find it quite interesting.

Very much enjoyed reading the article. It was both informative and fun. Just wanted to encourage you to keep doing the same because I wish more content on the web was this engaging. Yours is the writing style I appreciate most. Maybe because it’s the way I like to write to present information to my audience, or maybe because you referred to old school stuff that I experienced. Probably both.

Thanks for the effort! I will be following on social media.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words. We appreciate them.

The idea of Naked Security is to be as technical as needed (and occasionally very technical indeed), while eschewing the orotund jargonification and incomprehensible AOFOPAITKs (acronyms only for people already in the know) that litter so much of what passes for “writing” in the cybersecurity world.

By which I mean we aim to explain possibly complicated stuff, but in plain English.

We also subscribe to the doctrine that those who cannot remember history are condemned to repeat it, so we aren’t afraid of explaining where things started.

By which I mean that we like old-school stuff, too :-) (But not vinyl. I understand the attraction, but I don’t miss the poor audio quality one tiny bit. Nor do I miss my old CRTs.)