The internet is abuzz with news of a zero-day remote code execution bug in Microsoft Office.

More precisely, perhaps, it’s a code execution security hole that can be exploited by way of Office files, though for all we know there may be other ways to trigger or abuse this vulnerability.

Security researcher Kevin Beaumont has supplied it with the entirely arbitrary name Follina, and given that it doesn’t seem to have an official CVE number yet [2022-05-30T21:00Z], that name looks set both to stick and to be a useful search term.

(Update. Microsoft has assigned the identifier CVE-2022-30190 to this bug, and published a public advisory about it [2022-05-22T06:00Z].)

The name “Follina” was concocted from the fact there’s a sample infected Word DOC file on Virus Total that goes by the name 05-2022-0438.doc. The numeric sequence 05-2022 seems pretty obvious (May 2022), but what about 0438? This just happens to be the telephone dialling code for the area of Follina, not far from Venice in north-western Italy, so Beaumont applied the name “Follina” to the exploit as an arbitrary joke. There’s no suggestion that the malware came from that part of the world, or indeed that there is any Italian connection with this exploit at all.

How does it work?

Very loosely speaking, the exploit works like this:

- You open a booby-trapped DOC file, perhaps received via email.

- The document references a regular-looking

https:URL that gets downloaded. - This

https:URL references an HTML file that contains some weird-looking JavaScript code. - That JavaScript references an URL with the unusual identifier

ms-msdt:in place ofhttps:. - On Windows,

ms-msdt:is a proprietary URL type that launches the MSDT software toolkit. - MSDT is shorthand for Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool.

- The command line supplied to MSDT via the URL causes it to run untrusted code.

When invoked, the malicious ms-msdt: link triggers the MSDT utility with command line arguments like this: msdt /id pcwdiagnostic ....

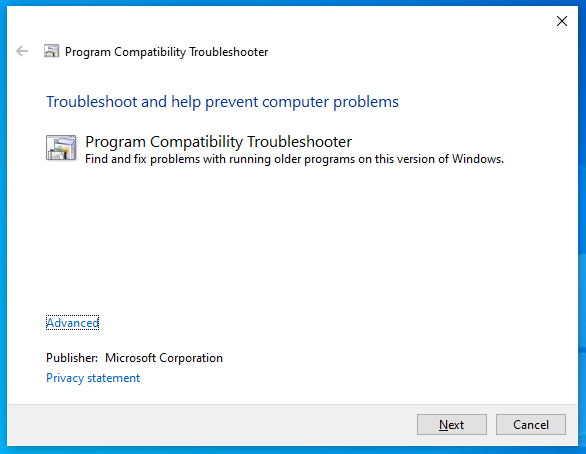

If run by hand, with no other parameters, this automatically loads MSDT and invokes the Program Compatibility Troubleshooter, which looks innocent enough, like this:

From here, you can choose an app to troubleshoot; you can answer a bunch of support-related questions; you can perform various automated tests on the app; and if you’re still stuck, you can choose to report the problem to Microsoft, uploading various troubleshooting data at the same time.

Although you probably wouldn’t expect to get thrown into this PCWDiagnostic utility just by opening a document, you’d at least see a series of popup dialogs and you’d get to choose what to do at every step of the way.

Automatic remote script execution

Unfortunately, it looks as though the attackers who discovered the “Follina” trick (or, more precisely, the attackers who seem to have used this trick in various attacks last month, even if they didn’t figure it out themselves) have worked out a series of unusual but treacherous options to put on the MSDT command line.

These options make the MSDT troubleshooter do its job under remote control.

Instead of getting asked how you want to proceed, the crooks have crafted a sequence of parameters that not only cause operation to proceed automatically (e.g. the options /skip and /force), but also to invoke a PowerShell script along the way.

Worse still, this PowerShell script doesn’t have to be in a file on disk already – it can be provided in scrambled source code form right on the command line itself, along with all the other options used.

In this case, the PowerShell was used to extract and launch a malware executable provided in compressed form by the crooks.

Threat researcher John Hammond at Huntress has confirmed, by way of launching CALC.EXE to “pop a calculator”, that any executable already on the computer can be directly loaded by this trick, too, so an attack could use existing tools or utilities, without relying on the perhaps more suspicious approach of launching a PowerShell script along the way.

No macros needed

Note that this attack is triggered by Word referencing the rogue ms-msdt: URL that’s referenced by a URL that’s contained in the DOC file itself.

No Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) Office macros are involved, so this trick works even if you have Office macros turned off completely.

Simply put, this looks like what you might call a handy Office URL “feature”, combined with a helpful MSDT diagnostic “feature”, to produce an abusable security hole that can cause a click-and-get-hit remote code execution exploit.

In other words, just opening up a booby-trapped document could deliver malware onto your computer without you realising.

In fact, John Hammond writes that this trick can be turned into an even more direct attack, by packaging the rogue content into an RTF file instead of a DOC file. In this case, he says, just previewing the document in Windows Explorer is enough to trigger the exploit, without even clicking to open it. Just rendering the thumbnail preview pane is enough to trip Windows and Office up.

What to do?

As convenient as Microsoft’s proprietary ms-xxxx URLs may be, the fact that they’re designed to launch processes automatically when specific types of file are opened, or even just previewed, is clearly a security risk.

A workaround that was quickly agreed upon in the community, and has since been officially endorsed by Microsoft, is simply to break the relationship between ms-msdt: URLs and the MSDT utility.

This means that ms-msdt: URLs no longer have any special significance, and can’t be used to force MSDT.EXE to run.

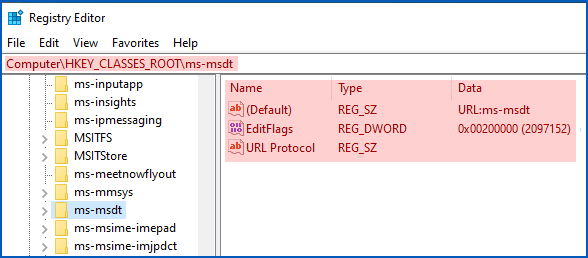

You can make this change simply by removing the registry entry HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt, if it exists. (If it’s not there, then you are already shielded by this workaround.)

If you create a file with a name ending .REG that contains this text…

Windows Registry Editor Version 5.00 [-HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt]

…you can double-click the .REG file to remove (the minus sign means “delete”) the offending entry.

You can also browse to HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt in the REGEDIT utility and hit [Delete].

Or you can run the command: REG DELETE HKCR\ms-msdt.

Note that you need administrator privileges to modify the registry in this way.

If you discover that you just can’t live without ms-msdt URLs, you can always replace the missing registry data later.

To back up the HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt registry key, use the command: REG EXPORT HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt backup-msdt.reg.

To restore the deleted registry key later, use: REG IMPORT backup-msdt.reg.

Just for the record, we’ve never even seen an ms-msdt URL before, let alone relied on one, so we had no hesitation in deleting this registry setting on our own Windows computer.

in case you need to reconstruct it after deleting it.

HOW SOPHOS PRODUCTS DETECT AND REPORT THESE ATTACKS

- Sophos endpoint products can detect and block known attacks conducted via this exploit as Troj/DocDl-AGDX. You can use this detection name to search your logs both for DOC or RTF files that trigger the original download, and for HTML “second stage” files that follow. You can also search for the name Mal/DocDL-C, which detects other attack documents that use a similar technique.

- Sophos endpoint products can detect and block attempts to trigger this exploit as Exec_39a (T1023). These reports will show up in your logs against the program

MSDT.EXEin the System folder. - Sophos email and web filtering products intercept attack files of this sort as CXmail/OleDl-AG.

Rob Meulendijks

Add msdt.exe to the application control option. This would make things way easier to manage.

Paul Ducklin

Unfortunately, App Control updates are only done in groups (on a monthly schedule) because they’re announced in advance so that customers have time to study the list first. This is because they aren’t designed to respond to threats, and may block operating system components. (This “preannouncement” was a result of customer feedback, so there’s a genuine reason for it :-)

Soren

Thanks for the post!

What about just renaming the “HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt” to “HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt_mitigated” – wouldn’t that break the relationship between ms-msdt: URLs and the MSDT.EXE utility, hence prevent the exploitation?

Would be easier for later undoing the work-around.

Paul Ducklin

I renamed the key on my test computer… but there is something unappealing about doing this across a network because it’s security through obscurity (and not very obscure if everyone uses the same replacement name!), with the underlying issue left in place.

You can back up the registry key with:

REG EXPORT HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt backup-msdt.reg

After renaming mine (in case I needed to redo my screenshot) I ultimately deleted it. The screenshot shows you what to add back if you really need to but I will wager you will never need to or even want to… my 2c.

Laurence Marks

Not really “security by obscurity” because if a hacker had access to the registry he wouldn’t bother to see what it said. He would simply insert the new key (whether creating it anew or overwriting an existing one), never bothering to look to see what was there first.

Paul Ducklin

What I meant is that if advice along the lines of,”Hey, just rename it to something like msdt-X instead” were to start circulating, it’s likely that many people will rename it not to something *like* msdt-X, but *to msdt-X exactly*, and then URLs starting ms-msdt-X: would become the new attack vector.

Joachim Trück

HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\ms-msdt doesnt exist on Server 2016 or Win10 1607 LTSC

So this versions are not affected?

Unfortunatly https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2022-30190 says its affected…….

Paul Ducklin

Well, Microsoft’s official workaround is to delete that registry key… if it exists. So if it is not there by default then I would simply say that you have a workaround in place by default!

Saying that Windows Server is “affected” doesn’t mean that the bug is exposed to immediate use by default, but merely that the bug has exists and would be exploitable on the platform if the configuration permitted.

For example, you would expect to be warned that Windows server was “affected” by a bug in (say) a specific Windows service even if you weren’t currently using that particular service, and even if it wasn’t activated by default… it would still need patching in case you turned that service on later, and you would probably apply any known workarounds for proactive safety anyway.

Likewise, you would consider Word (say) to be “affected” if there were a critical bug in the Print function, even if you didn’t have a printer.

(I’d hope you aren’t opening Word docs and receiving email on your servers either, thus further reducing the chance of getting infected even if the system is theoretically affected…)

Joachim Trück

-> I’d hope you aren’t opening Word docs and receiving email on your servers either,

Of course we receive most of our mails in an Outlook running on our Server 2016 RDS / citrix systems where most of our users work in microsoft office ;)

Falko Meyer

Just checked a Terminal Server Installation (2016): Registry key is in place.

Other servers don’t have it.

By the way the Terminal Server doesn’t have Office installed.

Paul Ducklin

From what I understand, given that the problem seems to be tricking an app that handles URLs into running an app that allows all kinds of risky command line options, this attack doesn’t actually require Office (apparently Outlook can be tricked,too). So, who knows whether other “launch tricks” might be found in due course?

In other words, if you were thinking of using the absence of Office as a reason *not* to apply the workaround…

…I wouldn’t do that!

Michael

Would disabling the policy setting “Troubleshooting: Allow users to access and run Troubleshooting Wizards” via GPO have the same effect as deleting the reg key?

Paul Ducklin

I don’t know. I suspect it would not or else Microsoft would probably have mentioned it as a possible workaround.

robert beaman

Tried the create a .reg file using notepad, w/ a .reg extension – I’m on Win 11 – a double click on the file prompted “do you want to allow this app to make changes….” saying yes generated prompt from Reg editor saying this- “Adding info can unintentionally change or delete values and cause…problems. if you do not trust the source…do not add it to the registry (paraphrased). Continue?

Clicking Yes gives this: Cannot import (file location). The specified file is not a registry script. You can only import binary registry files from within the registry editor.

Just an FYI – if there is specific detail that can be added to the article on “creating the file”, it would be helpful. i tested to see if i could create a basic file and run it at logon through a GPO for our users. Square one.

Paul Ducklin

I used NOTEPAD… and it worked… errr, I think.

Have you tried just using REG DELETE instead? It’s probably easier for scripting because you don’t need a second file for the data.

Larry Marks

Nah, you’ve got it wrong.

A couple of quotes from the article:

–More precisely, perhaps, it’s a code execution security ***hole.**..

–Security researcher Kevin Beaumont has supplied it with the entirely arbitrary name **Follina**,

Put those together and you have Follina Hole, more properly spelled “Fall in a hole.”

Frank Brants

We run a Server 2016 Terminal Server w/ Office 365 installed & a Registry search for “ms-msdt” found nothing.

I did find the executable (.exe & .ext.mui variants…) in several locations below C:\Windows – any thoughts on removing or renaming all instances of this file?

TAI,

Franko

Paul Ducklin

I assume (haven’t tried this) that the system file checker (is that the right name?) will notice the missing executable and try to restore it automatically…