UPDATE: 2022-01-28: We modified a few lines in the story to clarify how ZTNA configurations could have permitted the network operator to exercise greater control over devices on their network.

An attack on a technology vendor in December, 2021 – using ransomware known as Midas – leveraged at least two different commercial remote access tools and an open-source Windows utility in the process.

After the Sophos Rapid Response team was called in to help with analysis, we discovered indicators that the attackers had been active on the network for at least two months prior to the appearance of the ransomware on a domain controller and other computers on the network.

The target uses Citrix to virtualize all employee desktops, but the organization’s network topology was flat, with the entire network accessible behind its VPN. Windows Servers, run as virtual machine hypervisors, comprised most of the target’s physical devices. Flat networks with no segmentation are a risk factor in ransomware attacks. Had a zero-trust network access (ZTNA) setup existed, it could have helped limit the attackers’ ability to laterally move and connect to resources once they obtained a foothold on a user’s computer.

The attack involved repeated iterations of the threat actors creating Windows services designed to execute, on one machine at a time, several PowerShell scripts the attackers had placed on a few of the other compromised servers, which any other machine — VM or server — could just browse to over SMB. In a ZTNA configuration, properly configured access controls might have prevented the attackers from being able to leverage one compromised machine against another, disallowing user VMs from compromising other resources.

The target of the attack, who had been using another company’s endpoint security to protect their servers, never saw an alert that the attackers had entered the network. They executed commands, launched internal RDP connections, took advantage of already-installed commercial remote access software, exfiltrated data to the cloud, and moved files to and from one of the target’s domain controllers over a two month period, culminating in a deployment of the ransomware at the beginning of December, 2021.

Because there was a lack of log data, it remains unknown how the attackers initially accessed the domain controller, or how they had compromised and taken control over the Administrator account on that machine. But once they had, the attackers leveraged the permissions from that account — and the openness of the network topology — to spread backdoors and, later, ransomware to machines across the network.

Working the refs

While Midas is not as common a threat as some of the other ransomware families we more frequently encounter, the attackers seemed to follow a familiar playbook throughout the incident. They leveraged conventional Windows management tools and processes (such as PowerShell and the Deployment Image Servicing and Management tool), and commercial remote access tools (AnyDesk and TeamViewer) that would be less likely to trigger an anti-malware alert, using those tools to move laterally within the network and to exfiltrate files off the company’s network.

In this incident, the target’s IT staff had previously tested both AnyDesk and TeamViewer, as well as several other remote access tools, and were no longer using them. Unfortunately, they were still installed on some of the servers, which the attackers leveraged for their own benefit.

In some cases, the attackers deployed and used the open-source tool Process Hacker to identify and terminate the endpoint security products that the target was using to protect its systems.

The earliest indicator of compromise took place on October 13, when logs on one of the compromised domain controllers indicate that a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) connection took place between a machine on the internal network of the targeted organization and the domain controller. The RDP connection was a successful login by the Administrator account, from two different machines. It’s unknown how, prior to this point, the attackers gained access to the two internal machines they used to RDP into the domain controller.

The early phase of the attack took place between October 13 and November 2, after which there was no activity until three weeks later, on November 22. While it’s unusual in recent ransomware incidents to see that amount of dwell time by attackers on networks, they still can and do happen.

The attackers’ use of Process Hacker was only partially successful, as some of the machines began to detect and block the use of the Mimikatz credential harvesting tool on one of the company’s servers on Thanksgiving Day, November 25th. However, the investigation discovered that the attackers appear to have been successful running Mimikatz on a different server one day prior. A forensic analysis of the compromised server revealed a file called Passwords.txt that contained some of the harvested credentials.

Orchestration through PowerShell

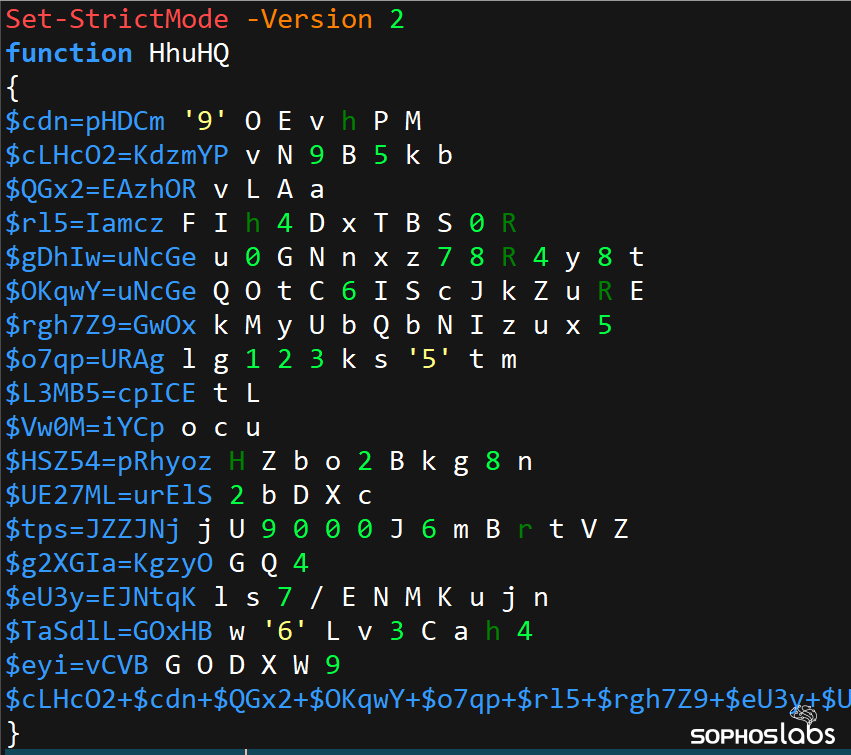

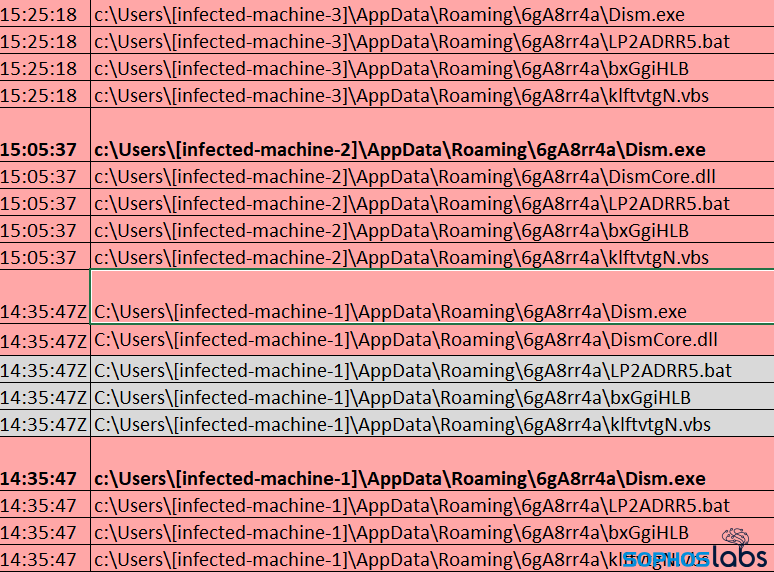

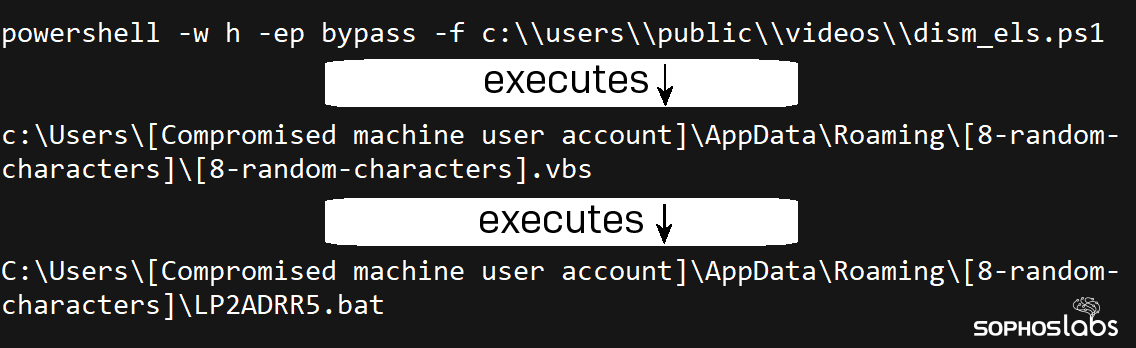

The attackers heavily relied on customized PowerShell scripts, in some cases installing them as Windows Services to execute them. They also orchestrated parts of the attack using Visual Basic Script and Batch files, executed using the DISM.exe utility that, under normal circumstances, is used to repair Windows installations that have become corrupted or broken.

During the first week the attackers were connected to the network, they clearly already had gained access to a number of internal machines within the target’s organization. They were uploading various PowerShell scripts into the TEMP directory of some of the machines they controlled, then created Windows services on other machines they could access that would call those scripts from over the network and execute the scripts hosted on those other machines.

While many of the PowerShell scripts used randomized filenames, a few of the filenames gave hints as to their purpose, such as “dism_els.ps1” which the attackers executed on the server where the DISM tool was then used to install a backdoor. Twenty minutes later, the same command was executed on a second server. Another script, “adtest.ps1” may have been used to verify whether they had domain administrator privileges on the server.

The attackers used oddly complex combinations of scripts to accomplish a single task. For instance, a PowerShell script would execute a Batch file, that in turn would launch a PowerShell script, that would run a command to invoke a DLL sideloading tool to inject a system process with the malicious DismCore.dll payload. We saw several instances of Visual Basic Script launch PowerShell, which then launched a batch script that invoked DISM to load DismCore.dll. The files involved had names of four, eight, or twelve random alphanumeric characters in length. Some of the PowerShell scripts used the file suffix .log instead of the default .ps1. A few used no file suffix at all.

The attackers were methodical, iterating through the same process repeatedly on different machines between October 13 and 19, leaving a number of servers backdoored on the target’s network. But then the attackers suddenly stopped connecting and taking actions on the 19th, and resumed on November 2nd.

On November 2nd, the attackers logged on and iterated through the service-creation/PowerShell execution process on two more desktop machines, with an indication that the attackers had used AnyDesk 13 separate times on one of the servers we found had been compromised during the earliest phase of the attack. After this behavior was observed, there was no more activity for three more weeks.

No Thanksgiving

After a lull in activity, the attackers resumed their work on November 22, installing services and using those service to execute PowerShell scripts running on other internal machines that had previously been compromised.

The attackers only ran a single PowerShell script one time on the 22nd, then a day later installed more services on three other machines and used those services to execute PowerShell scripts.

On November 25th, logs indicated that one of the compromised domain controllers wrote out a file named Passwords.txt under the path C:\Compaq\!logs\ on its local storage, but it wasn’t until after midnight that night that the target’s antivirus software detected Mimikatz running on a different server. A number of other internal RDP connections were made between the 25th and 29th, and then the trail went cold as the attackers laid low.

The final phase

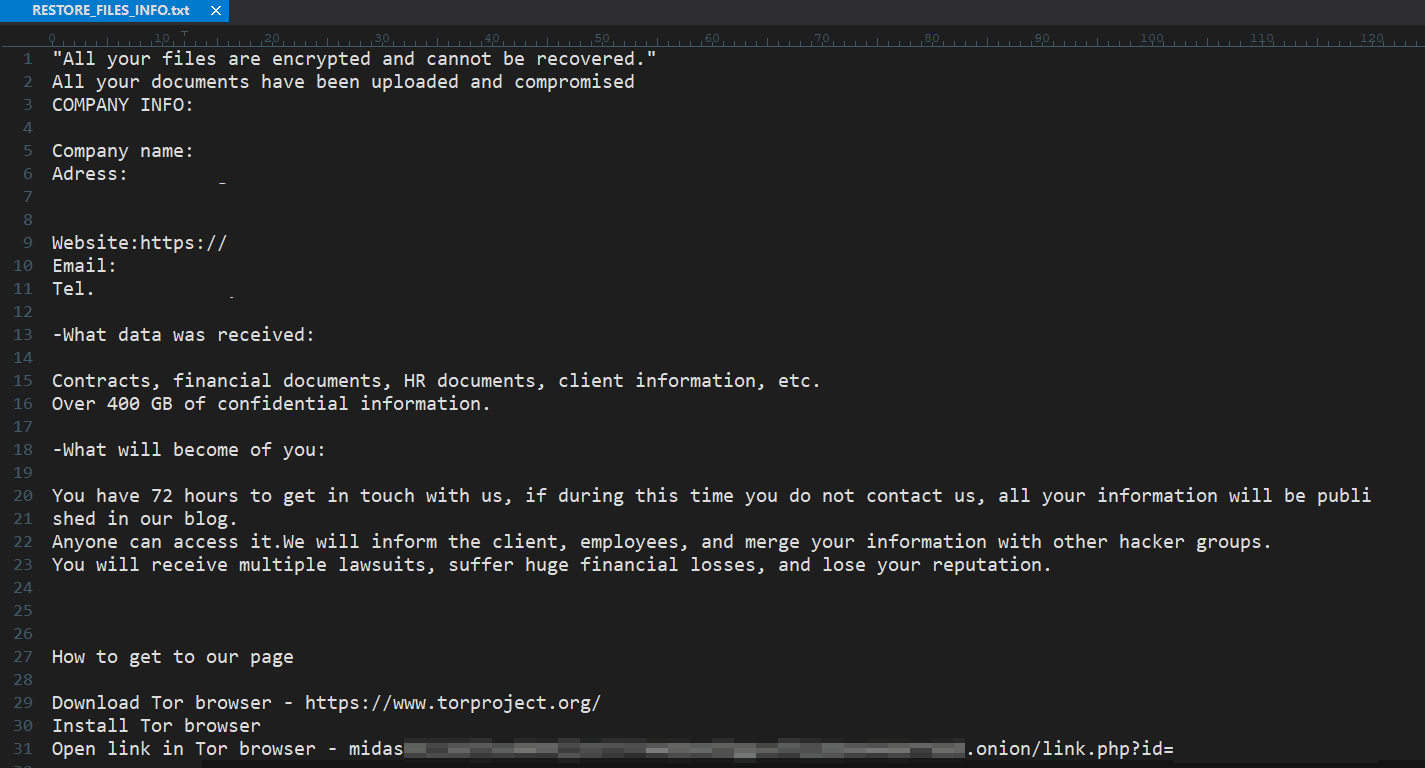

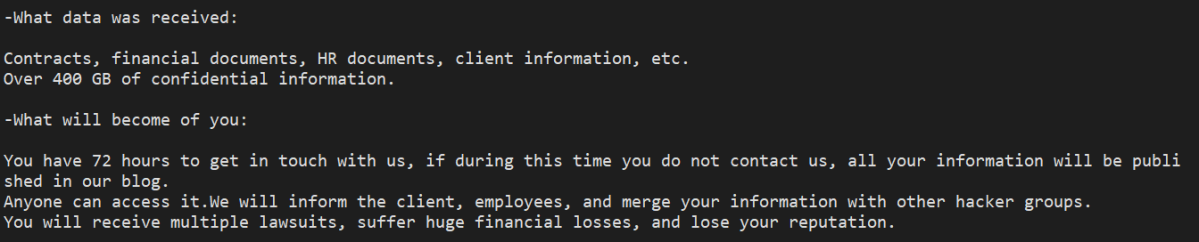

More than a week later, late at night of December 7 in the target’s time zone, the attackers began deploying the ransomware binary to machines on the target’s network. The file was dropped on the path C:\hp\ and its filename included the name of the target organization. The same directory was where whoever was deploying the ransomware also saved a copy of Process Hacker.

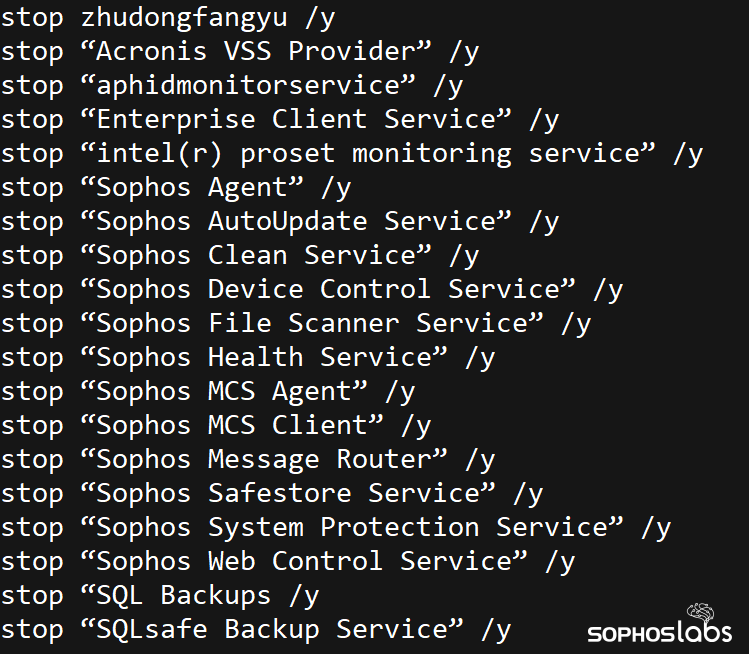

The attackers then ran Process Hacker under a service they created called KProcessHacker3, and presumably used it to terminate the antivirus software that had thwarted the execution of Mimikatz several weeks earlier.

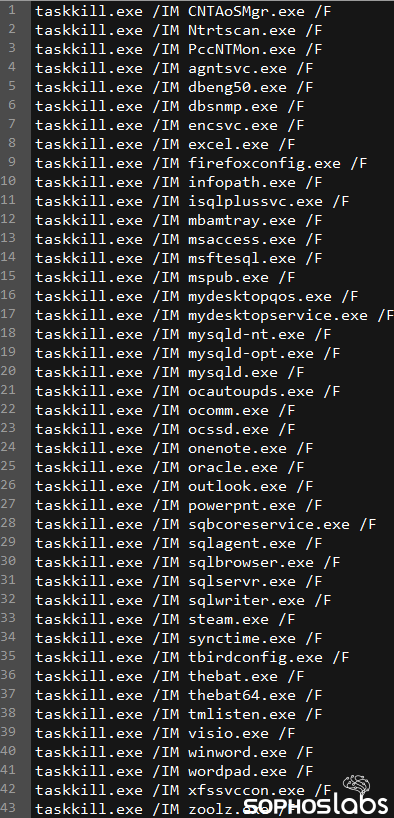

We also recovered PowerShell scripting commands that the attackers used in an attempt to shut down 46 processes, and 216 services, by name. These included services like MSSQL, various backup tools, office applications, and services tied to security software from McAfee, Kaspersky, Trend Micro, and Sophos, among others. The script that terminated services and processes had several redundant listings, which indicates the attackers were adding entries in the lists by hand, and not checking for duplicates.

A few minutes later, the attackers moved copies of two ransomware binaries, named <target>local.exe and <target>share.exe (with the target organization’s name in the filename, redacted here) to an internal server and executed it.

They then iterated through this same process on several other servers on the network: Installing a Windows service that was used to execute Process Hacker, then a few minutes later copying and executing the two ransomware binaries. The attackers took their time, only doing this about once an hour for the next several hours.

Later that day, December 8, the target engaged with the Rapid Response team after they discovered ransom notes (and that servers weren’t doing what they were supposed to be doing).

Fortunately for the target, the damage was limited only to a small number of servers. With the Rapid Response engagement, analysts installed Sophos endpoint tools onto machines across the organization, which then detected and blocked the attackers subsequent use of DISM and Process Hacker, and the attempted deployment of additional ransomware executables to other machines on the network.

The takeaway

The attackers involved in this Midas ransomware attack relied heavily on a process in which they installed new Windows services that were used to execute PowerShell scripts. These services had quite obvious-to-the-human-eye names that were just random jumbles of letters and numbers, but the target was not monitoring computers on its network for the creation of these services, or lateral movement of any kind between the servers.

The attackers also relied heavily on both RDP and third party remote access tools that the company did not typically use in the course of its business. We counted at least 14 different open-source or commercial remote access tools that had been previously installed and left in place on the compromised machines. Needless to say, this provided a wealth of opportunities for misuse. One of these may have been the attackers’ source of initial access to an internal computer. The bottom line advice is this: if you install remote-control tools, and you’re not actively using them, the right move is to uninstall them completely from the machine.

Monitoring for unusual activity by non-malicious programs or Windows management tools should be de rigeur for IT security teams, as it’s very difficult for an endpoint security product to recognize the difference between a benign or malicious use of a legitimate tool. Application allow-listing can further restrict the ability of a threat actor to use their preferred toolset.

This standard advice we’ve given for years rings true in this case, as well: The attackers would have had a much harder time if the target had used multi-factor authentication on their internal services and machines, and a network that was segmented into discrete areas with limited access between them. But the effort and planning will be worth it if you break a hacker’s heart by ruining their attack.

Detections and guidance

Sophos will detect some malicious use of DISM as a DynamicShellcode exploit, while not triggering a false-positive detection on the benign file, itself. The Process Hacker utility is detected as a potentially unwanted app (PUA) and the Midas ransomware binaries were detected as Troj/Ransom-GLY. Other components of the attack may be detected as Troj/PSInj-BI (PowerShell scripts), Troj/MSIL-SDB (the malicious dismcore.dll), Harmony Loader (PUA), or ATK/sRDI-A (the sRDI DLL sideloading tool).

SophosLabs has published a partial list of Indicators of Compromise relating to this attack to the SophosLabs Github, and redacted certain details from this report and screenshots, to protect the identity of the targeted organization.

SophosLabs wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Jason Jenkins of the Rapid Response team for his work on the post-attack analysis.

Steve B

Seems this is happening more and more often. Latest example is the BOGOF experts Safestyle – rumblings are their IT systems were hacked and shut down this week from what is believed to be ransomware for a large sum of bitcoin. They’ve not manufactured a window since, can only pay their sales reps basic pay and no commissions, told their staff the shutdown’s due to a GDPR IT problem and not to speak to the police or press.