Two weeks ago, after three software audits and three months of live testing, a cryptocurrency startup called MonoX introduced what it described as “the premier bootstrap decentralized exchange, Monoswap”.

In an announcement on 23 November 2021, the company declared:

MonoX will revolutionize the DeFi ecosystem by fixing the capital inefficiencies of current protocol models. With lower trading fees, capital efficiency, and zero-capital token launching — MonoX will expand the capabilities of DeFi.

DeFi, as you probably know, is an acronym for (or, for the linguistically strict amongst us, an ellipsis of) the term decentralised finance, and is typically used to refer to electronic trading that doesn’t rely on any individual company or government department for record keeping.

By using distributed ledgers known as a blockchains, a sort of community-operated bookkeeping venture where transactions are agreed and recorded by consensus, cryptocurrencies and digital contracts don’t need to be managed by a single authority such as a central bank or a payment card company.

Blockchain technology therefore brings lots of opportunity, as you are no doubt aware from the number of Why Not Inve$t In Our Brand New Cryptocoin Deal$ Right Now emails that are getting caught up in your spam filter these days.

And plenty of risk, too, as MonoX discovered almost as soon as it went live last month,

Despite the audits and the testing, MonoX seems to have made an interesting blunder in how it handled balance changes during transactions.

This has apparently already cost the startup a massive $31,000,000 in lost funds, thanks to an automated series of rogue transactions that the company failed to think of, and therefore didn’t program against.

Paying yourself considered harmful

As far as we can see, the software flaw that MonoX overlooked was triggered if you transferred value from one of your own MonoX cryptocoins…

…back to yourself, a bit like doing a bank transfer from your own account directly back into your own account.

You’d imagine that your regular bank would prevent you doing such a thing, on the grounds that it would [a] be pointless and [b] probably be a mistake.

If you were absolutely determined to do it anyway, perhaps in a misguided attempt to get a bunch of deposits on the record to make your business look busier that it really was, you could always try doing it as two separate transactions.

For example, you could withdraw $100 in cash from a teller, then join the back of the queue and pay the $100 straight back in, assuming you were willing to accept a modest overall loss from any withdrawl and deposit fees that might apply.

These days, you’d expect your balance to go down by $100 as soon as you did the withdrawal, and you’d certainly expect, in the time it took to return to the teller to pay the $100 back in, that the previous transaction would have gone through already.

Even if that didn’t happen, you’d ultimately expect to see both transactions listed on your statement, in the same order you conducted them: $100-plus-fees out, and $100-less-fees back in.

What you wouldn’t expect, however (not least because your bank wouldn’t still be in business if it let people get away with this), is that if you could get the second transaction processed quickly enough then it would overwrite the first transaction altogther, leaving your account credited with a $100 deposit, but with no record of the immediately preceding withdrawal.

Holed below the waterline

Sadly, it seems that something along the lines described above is what holed MonoX’s ship below the waterline:

The exploit was caused by a smart contract bug that allows the sold and bought token to be the same. In the case of the attack, it was our native MONO token. When a swap was taking place and tokenIn was the same as tokenOut, the transaction was permitted by the contract.

Any price updates from swap from tokenIn and tokenOut were independently verified by the contract. With tokenOut being verified last, this caused a massive price appreciation of MONO. The attacker then used the highly priced MONO to purchase all the other assets in our pool and drained the funds.

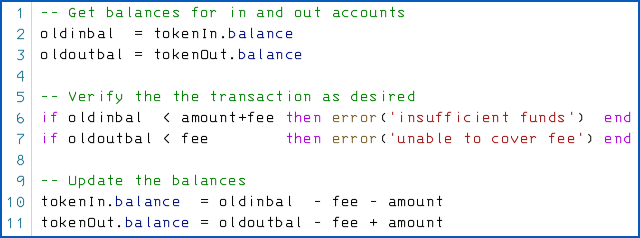

The explanation isn’t entirely clear, perhaps because English isn’t the author’s first language, but it does indeed sound as though the “smart contract” code went something like this:

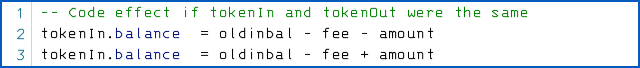

As you can see, the code above doesn’t work if tokenIn and tokenOut refer to the same account, because the last two lines then become equivalent to:

The deduction in the first line is immediately undone by the variable assignment used to effect payment in the second, so you’re up by (amount - fee) cryptocoins.

You’re supposed to end up with an overall outcome of (amount - amount - 2*fee), which simplifies to a debit of (2*fee) – one fee for the withdrawal; the other for the deposit – as you would expect.

According to MonoX, some of the funds acquired in this way have been pushed through a so-called tumbler or transaction mixer, presumably to attempt to disguise their source so they can be spent again without arousing suspicion.

What next?

Perhaps encouraged by the recent $600m Poly Networks hack, where the company somehow manged to woo the perpetrator sufficiently well that most of the the funds were returned, MonoX says that it has “[t]ried to make contact with the attackers to open a dialogue through submitting a message via transaction on ETH Mainnet”.

In other words, the MonoX team have used the comment field in an Ethereum transaction as a way of asking for the appropriated funds back.

MonoX also stated that it “will file a formal police report”, though it’s not clear whether that has happened yet.

We’re guessing that it might complicate MonoX’s negotiations with the perpetrators if the matter is now in the hands of the police.

Indeed, the next question is, “Did the attacker actually break any laws?”

In some jurisdictions, knowingly exploiting software bugs to circumvent protection or to achieve results that are clearly at odds with expected behaviour can leave you open to criminal or civil action.

No less a company than Google found that out back in 2012, when it was fined for sneakily circumventing anti-tracking protection in Apple’s Safari browser.

Also, in many if not most countries, you’re expected to report and return any bank deposits that clearly weren’t intended for you, instead of being allowed to profit from the bank’s mistake.

But the whole point of DeFi is its decentralised, freewheeling, libertarian, not-regulated-by-the-man nature.

So, as non-lawyers, we have absolutely no idea what the regulatory situation is likely to be in this case, if indeed we ever find out which jurisdictions and which regulations would apply anyway.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments (you may remain anonymous if you wish)…

Anonymous Coward

What do I think? I think it’s best not to trade cryptocurrencies.

Just asking for trouble if you do.

At least, not with money you can’t afford to donate to organised crime.

Kyle

By that logic we shouldn’t use reserve bank money either, because even more of that gets ‘donated’ to organised crime.

Cryptocurrencies don’t exist to commit crime. Hell, they aren’t even anonymous most of the time. The FBI has arrested a lot of morons thinking they care wire transfer to Bitcoin and then purchase narcotics.

Cryptocurrencies exist to decentralise your finance from central authorities. People have legitimate reasons to do this, such as preventing the value of your money being tied to the success of your own country (which for some third worlds is pretty abysmal). It also stock-level returns on investment and is (mostly) safe from recession.

Anonymous

Seems like someone was looking out the window the day they taught semaphores in CompSci 101.

Anne

Much too volatile. A bad idea to invest in crypto. Funding organinized crime is a prime suspicion of crypocurrency.

BF

Crypto Currency is a ponzi scheme or even pyramid scheme… Along with a giant waist of electrical power and should be banned or not allowed to trade with established monetary systems that are regulated.

Raymond E Rogers

I could point them to various programs that “Formally” verify software; of course one has to explicitly state specifications to verify against :) But, like a lot of contemporary software, I presume that’s too much trouble; after all it’s just a few bits :)

Raylund

When I were studying in UK many years ago that I heard a story. At that time, if you withdraw money at one ATM and fast enough to go to another ATM, you could withdraw again even you didn’t have enough money in the bank.

I’m always thinking when coding a system, asking the corresponding industry professional better than thinking in terms of oneself point of view. Theory/logic is one part, experiences and practices are another parts.

Paul Ducklin

I’ve heard of ATM withdrawals bypassing the daily limits of the era by making two withdrawals really quickly. (I suppose that story might extend to overdrawing your account.)

But I have never heard tell of cases where the first withdrawal would not ultimately catch up with you. In other words, although you might get more money in your hand in one night than the system was supposed to permit, all the money would be correctly docked from your account by the next day, so you would not end up getting anything for nothing.

Raylund

Yes Paul, normally speaking will be like that. But I heard stories that some students after graduated and just before leaving UK for their home countries, they withdraw like that. I don’t think the banks will chasing them for a few hundreds quids with enforcement and going to their home countries. And yes, they’re criminals and the system cannot handle this at that time.

Paul Ducklin

In today’s global world, it’s hard to guess who’ll end up owning which bank… could end rather alarmingly if the bank you’re now using back home suddenly buys or gets bought by the bank you defrauded out of £200 back in 1986 and merges the customer data.

(My point was not that you couldn’t defraud a bank like that – after all, if you intend to flee from debt by leaving the country and never coming back, you could do it in many ways, even or perhaps especially as a student. My point was that no withdrawals would ultimately get “overwritten and forgotten” in the process, so your ultimate liability would remain, which is a bif different from this situation, where a debit was recorded, then apparently entirely replaced in the ledger by an equivalent deposit, thus wiping out the preceding withdrawal.)

Charles

This is pretty much what fast-change artists do — confuse the mark with a series of transactions done quickly, such that the end result is getting more back than they gave, on what started as an even exchange.

Gary

This reminds me of the old Abbott and Costello routine “Do you have two 10’s for a 5?”

Kent Higgins

I think it is madness to not have QC that is well staffed and funded and listened to by the management. Said QC staff should have no basis for water-cooler discussion with developers; they need to be independent. It ought not need be said that nothing new works right first time around. I do understand the rush to get product out the door, but the cost of bad product on the street is higher than delay.

Back in the 1970s, when ATM machines were new, I moved to Princeton, NJ. Knowing I would need such a card to draw cash for unexpected travel, I went to my back to obtain a card. “Sorry,” they said, “You have to be a customer for six months before we can give you a card.” Asked why that was, they explained that their ATM machines would dispense an unlimited amount of cash to a cardholder because it did not verify the balance first. I moved myself and my money from that bank.