In May, we reported initial findings on RATicate, a group of actors spreading remote administration tools (RATs) and other information-stealing malware at least since last year. We tracked multiple malicious spam (“malspam”) email campaigns from the group, with attached installers that usually posed as documents related to financial transactions.

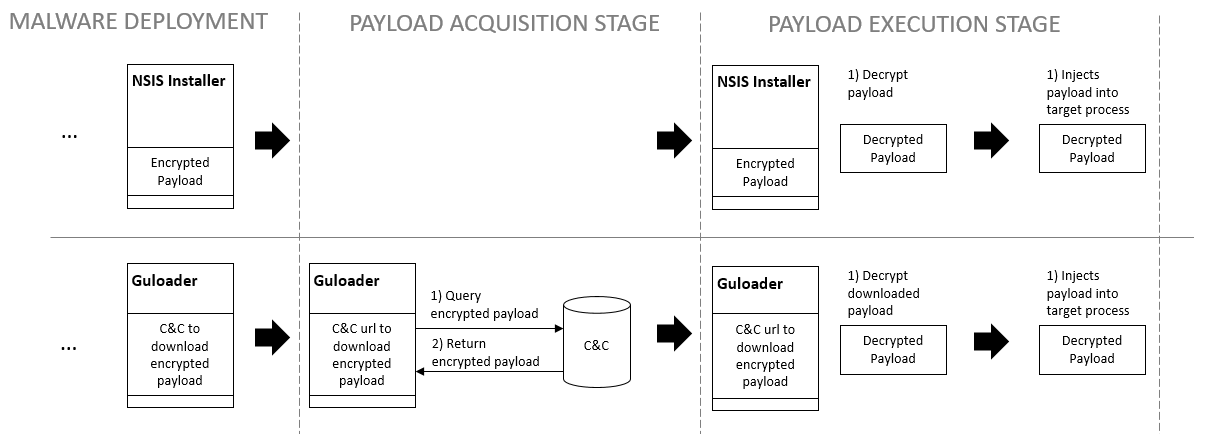

In recent campaigns, the group’s tactics have shifted, as the actors employed a new malware “loader” in order to unpack and install RAT and infostealer payloads in a more stealthy way. As discussed in our original report, the RATicate group had since last November been packing their RAT and infostealer payloads for deployment via e-mail exclusively with custom NSIS installers. But in February, the group started to switch to a new delivery mechanism. Initially identified (by researchers at CheckPoint) as Guloader, the new Visual Basic 6-based installer was tied to a publicly-marketed installation builder called CloudEyE.

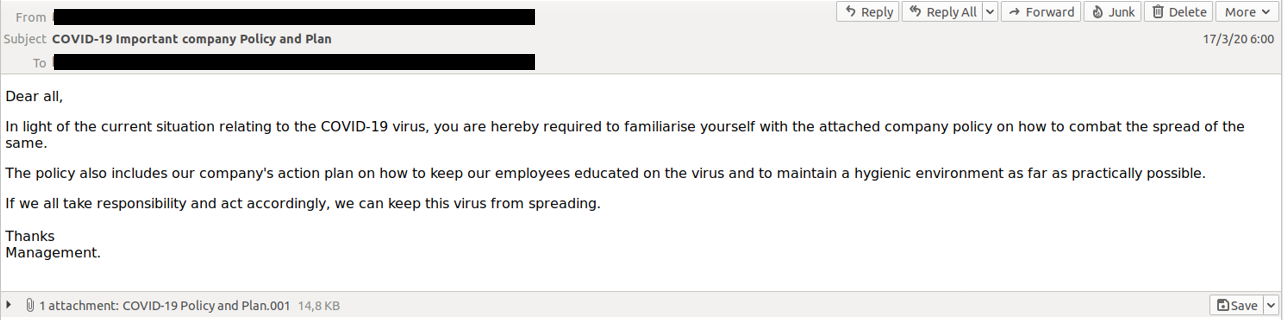

It was also during this period that we saw the RATicate actors begin to use the COVID-19 pandemic as a hook to get victims to open the installers. An email campaign attempting to distribute the Lokibot password-stealing malware used a message attempting to spoof company emails on COVID-19 response policy as a lure to get targeted users to open the malicious attachment:

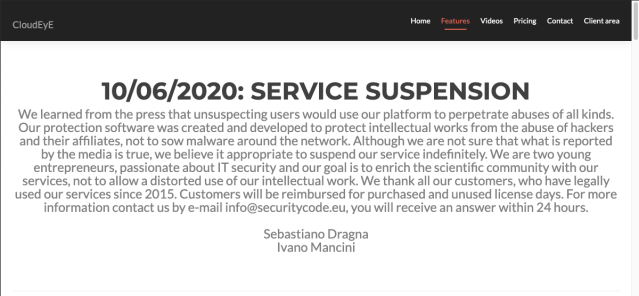

On June 10, CloudEyE announced that they had suspended sale of their installer because of “abuse” of their platform, and were refunding customers for unused portions of their licenses. We contacted the individuals associated with the Italian company behind CloudEyE in an attempt to gain further information about the RATicate actors. They confirmed that the malware signatures we provided were associated with three accounts that used their service, with the majority of them associated with a single account. But the CloudEyE developers would provide no further data, citing Italian privacy law. CloudEyE has recently returned to service, claiming tighter controls on customer accounts.

Despite the suspension of CloudEyE operations, RATicate remaims very active. The group has switched back to the NSIS installer for its most recent campaigns, and is continuously making improvements to its infrastructure and distribution methods. We continue to monitor the group to ensure that its malspam messages remain blocked by Sophos.

Change in delivery

Between November 2019 (when we began to track the activity of this group) and March 2020, we identified at least 14 separate RATicate campaigns connected to the same set of command and control (C2) infrastructure. These campaigns, detailed in our previous report, distributed payloads that included AgentTesla, Formbook, Lokibot, Netwire and Betabot.

However, starting in February 2020, we began to see the actors shift to a different delivery vehicle for their malware. CloudEyE is a multi-stage “loader” with a wrapper written in Visual Basic. It contains a shellcode which is responsible for downloading encrypted payloads and injecting them into a remote process.

Because the download URL used by the loader was short-lived, it was difficult to recover the payload they were downloading at the moment. However, we were able to recover downloaded files connected to these installers [from Virus Total submissions] and to decrypt them in order to analyze the final payloads.

Despite the new delivery method, we were able to link the campaigns to the RATicate group based on a number of factors. The payloads of the campaigns using both types of installers delivered the same families of remote administration tool (RAT) and information stealing malware, and they shared the same command and control (C&C) infrastructure. For example, these two campaigns used the exact same C&C URL:

- NSIS Campaign 14 (2020-03-01): allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/jl2/link.php

- CloudEyE Campaign (2020-03-19): allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/jl2/link.php

Another detail pointing to the connection to RATicate was the overlap in the companies targeted by the campaigns using both installers. And both the NSIS and CloudEyE campaigns used the same infection chain methodologies (outlined in our first report on RATicate).

We also that during initial deployment of CloudEyE, there was an overlap with the NSIS campaigns. This led us to believe that the group was testing CloudEyE before fully switching from NSIS-based to CloudEyE-based campaigns. As the CloudEyE campaigns increased, the NSIS-based campaigns ended. And when CloudEyE’s developers suspended operations, the NSIS-based campaigns tied to RATicate resumed.

The curious “legitimate” malware installer

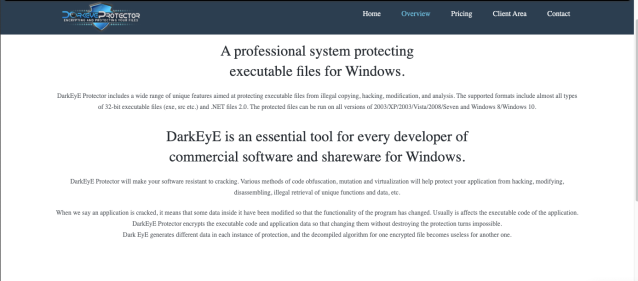

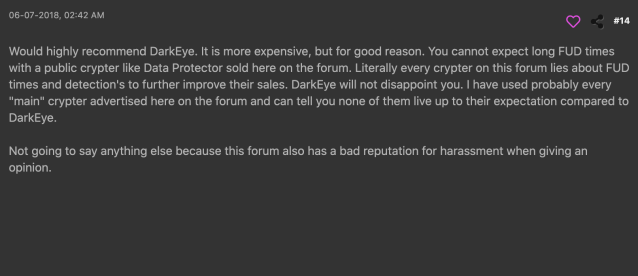

CloudEyE’s developers, Sebastiano Dragna and Ivano Mancini, have been marketing “protector” services for software developers for at least the past five years. Their original product was called DarkEyE Protector, intended to allow developers of commercial or shareware software to enforce software licensing schemes, prevent the copying or reuse of software components, and harden applications against reverse engineering or analysis.

Unfortunately, it was also usable as a malware “crypter”—and RAT operators generally praised its use as a “fully undetectable (FUD) crypter”, even as a subscription service. Various versions of DarkEyE were offered “cracked” on hacker websites and boards as well.

Late last year, Dragna and Mancini evolved DarkEyE into CloudEyE with the addition of cloud and web-based software installation features. Unlike DarkEyE (or NSIS), CloudEyE is a tool for building a two-stage installer—Instead of having the final payload embedded, as NSIS does, the CloudEyE loader pulls the final payload down from a remote URL.

CloudEyE can be used to deploy the encrypted payload to a webserver, or to a cloud storage service such as Google Drive, Dropbox or Microsoft’s One Drive. Since the payload is an encrypted blob, it evades detection by cloud storage security checks. The RATicate actor used Google Drive in an early campaign that appeared to be a test-run with CloudEyE.

Below: A video posted by the developers of CloudEyE demonstrating deployment of an encrypted payload using Google Drive.

A similar demonstration showing the use of CloudEyE to deploy a “protected” executable to a private web server.

When used in a malware campaign, this approach significantly complicates analysis. Network analysis of a CloudEyE payload in an email would only yield the URL used for the second stage. If the URL is no longer working because the server is down or the protected file has been removed it’s impossible to retrieve what would have been the final payload. Furthermore, deploying payloads through a cloud service or other legitimate third-party service provider (as RATicate did with Google Drive) makes it even more difficult to track the group behind the malware.

However, there were a number of things that made identifying RATicate as the actor group straightforward:

- The use of the same C&C infrastructure as used in previous campaigns,

- The commonality of infection chains across both NSIS and CloudEyE campaigns (with the installers either contained in a .zip archive file attached to an email, or downloaded by a weaponized document attached to an email from RATicate’s C&C infrastructure)

When presented with data from all of the campaigns associated with RATicate, the developers of CloudEyE confirmed that all of the campaigns they had data to verify came from three CloudEyE user accounts—with the majority coming from a single account.

Profiling CloudEyE campaigns

There were several artifacts of CloudEyE that made it possible to track the RATicate actors’ use of the tool. For web server deployments of the payload via CloudEyE, the name of the encrypted payload is linked to the URL for the payload’s C&C, as shown in these examples from the RATicate campaigns we found:

| Encrypted payload name | Payload C&C |

|---|---|

| gold_encrypted_41109B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/gld/link.php |

| bill_encrypted_9743D3F.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/bill/link.php |

| apslo_encrypted_2A0A9B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php |

| j2_encrypted_6637930.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/jl2/link.php |

| pope_encrypted_5A46720.bin | stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/pope/logout.php |

| frega_encrypted_30238C0.bin | castmart.ga/~zadmin/lmark/frega/link.php |

We noted the same relationship in CloudEyE campaigns from other threat actors, so it’s apparent that the CloudEyE builder uses a pattern to generate the name it uses for encrypted payloads.

Additionally, the hexadecimal number at the end of the payload name generated by CloudEyE is always 7 characters long, and appears to be a randomly-generated number, or is the result of a hash, timestamp or other build-specific input. It can be used to tag or identify specific campaigns or builds of the payload, and used in tracking campaigns and analyzing how the actors operate. For example, the following table shows names of encrypted payloads that all connect to the same C&C URL. Since these files were seen on different dates, we believe that they were different campaigns using the same payload, allowing us to track and cluster the campaigns.

| Date | Encrypted payload name | Payload C&C |

|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-16 | apslo_encrypted_83062FF.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php |

| 2020-03-19 | apslo_encrypted_31439B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php |

| 2020-03-23 | apslo_encrypted_2506950.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php |

| 2020-04-15 | apslo_encrypted_2A0A9B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php |

In other cases, we found CloudEyE samples with different versions of the installer which point to same encrypted payload name. This could mean that they were used as part of the same campaigns, but that the installers were rebuilt in CloudEyE in order to avoid detection based on a hash of the file.

| FirstSeen | Encrypted payload name | Final Payload C&C | Hash |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-31 | apslo_encrypted_2A0A9B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php | f521d91130e9f9d78e90a78f0744044051e0e64c212c33dd6be9aaa6201cc882 |

| 2020-04-08 | apslo_encrypted_2A0A9B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php | 6291b8da2debcf4e4e03607f4bd32fdf56a07e408b5cdfb47e212cf56726f11f |

| 2020-04-15 | apslo_encrypted_2A0A9B0.bin | allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php | 84d01e09fce89380d755c8e3c69055ab8c07ce547c3e43cf2437028d8581c564 |

Profiling the threat actor

In our first report on RATicate, we noted that we suspected this threat actor may be acting as a Malware as as Service (MaaS) provider, selling third-party threat actors both the delivery and command and control infrastructure for malware packages. It was one explanation for why each RATicate campaign we identified delivered very different malware families.

During our initial investigation of RATicate, we were able to use junk files packaged with the installer to identify campaigns. That wasn’t possible with the CloudEyE installer, but we were able to track the full infrastructure used, and use that and the filenames generated by CloudEyE as the basis for analysis of campaigns.

What we found further suggested that RATicate was acting as a MaaS, and third party threat actors were using RATicate’s infrastructure to deploy the malware of their choice. We can see there was no synchronization between the different campaigns, and that each of the different malware families used specific URLs in the C&C infrastructure that include a directory name that could be associated with each specific third-party actor, or with a specific campaign:

| C&C | Family | Analysis Option 1 | Analysis Option 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/lanre/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: lanre | actor_tag: lanre |

| castmart.ga/~zadmin/lmark/frega/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: frega | actor_tag: frega |

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/ap0s/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: ap0s | actor_tag: ap0s |

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/gld/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: gld | actor_tag: gld |

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/bill/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: bill | actor_tag: bill |

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/jl2/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: jl2 | actor_tag: jl2 |

| allenservice.ga/~zadmin/lmark/h0ly/link.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: lmark campaign_tag: h0ly | actor_tag: h0ly |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/pope/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: pope | actor_tag: pope |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/aus/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: aus | actor_tag: aus |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/fit/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: fit | actor_tag: fit |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/moh/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: moh | actor_tag: moh |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/kha/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: kha | actor_tag: kha |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/bud/cyc/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: bud campaign_tag: cyc | actor_tag: cyc |

| stngpetty.ga/~zadmin/covid/cl/fre.php | Lokibot | actor_tag: covid campaign_tag: cl | actor_tag: cl |

| ggautosrep.ga/~zadmin/amo/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: amo campaign_tag: – | actor_tag: amo |

| castmart.ga/~zadmin/beta/aps/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: beta campaign_tag: aps | actor_tag: aps |

| ggautosrep.ga/~zadmin/am/logout.php | Betabot | actor_tag: am campaign_tag: – | actor_tag: am |

The relationship between encrypted file names and payloads’ C&C URLs and the patterns they follow, suggest two possible scenarios. Either all this infrastructure belongs to one threat actor—RATicate group—and the group operates all these campaigns, or the RATicate group sells MaaS services—providing the infrastructure to other threat actors which finally use the infrastructure to infects the targets they want. Based on the research and the information we’ve collected until now, all evidence points to the second option.

Back to old tricks (for now)

On June 10, Dragna and Mancini shut down CloudEyE accounts after being informed that their tool was being used by multiple malware operators. The CloudEyE packaging tool had been provided as a subscription service, with central control over functionality maintained by a licensing API. They claimed they were alerted by press shortly after their service was identified by CheckPoint as being “Guloader.”

Shortly after CloudEyE’s shutdown, we observed new RATicate campaigns based on the NSIS installer. The group remains active. Based on our observations thus far, we believe RATicate group will continue to look for ways to apply new tools to its service and continuously attempt to improve its delivery of malware for its customers.

On July 11, CloudEyE resumed operation with the following note from Dragna and Mancini: “Following an internal investigation aimed at verifying abuses carried out with our protection software, we decided to intensify our internal control policies aimed at limiting possible future abuses. Each contribution or report will be analyzed by the staff with the utmost attention and if ascertained, the account will be suspended immediately.”

The new measures include the use of a hardware fingerprinting tool, called a hardware ID (HWID) grabber. However, those wanting to download this new “security feature” required to use the CloudEyE service will have to turn off malware protection, as it is currently detected as malware by 17 security tools—including Sophos and Microsoft’s Windows Defender.

Even with the new “security features,” there is no guarantee that CloudEyE will not not be used once again as a tool by RATicate and other malware operators. While Dragna and Mancini told us they were moving to ban bad actors from using the service—including the ones we pointed out to them—our assessment is that bad actors have long made up a significant portion (if not, as CheckPoint recently asserted, a majority) of their customer base. Abuse of legitimate services is difficult to prevent by simply requiring hardware tokens, banning IP addresses and locking out specific user accounts. Given the reputation of their previous tool, the illicit demand for the service will not fade away.