In 2021, the UK’s highest-denomination banknote – or, more precisely, the biggest note in general circulation – will go plastic.

New banknotes typically mean new portraits, as when a plastic Sir Winston Churchill supplanted a paper Elizabeth Fry on the fiver in 2016, and the author Jane Austen replaced the scientist Charles Darwin on the tenner in 2017.

Like the £10, the £20 will transfer its allegiance from the sciences to the arts in 2020, with economist Adam Smith booted in favour of artist JMW Turner, after whom the prestigious Turner Prize is named.

(To be clear, there are at least two portraits on each banknote, because the reigning monarch is by tradition always on the front – it’s the people on the back who get swapped out when new notes are commissioned.)

So here’s a question for you – and don’t cheat by looking up the answer online or by peeking in your wallet…

…who’s depicted on the current £50 note, and what are they known for?

Chances are you don’t know.

Most people, at least in the UK itself, have no idea who’s commemorated on the fifty, for three main reasons: we don’t use cash that much any more; we’ve never taken much notice of the back of banknotes- everyone knows Her Majesty is on the front but the famous person on the other side is usually forgotten; and £50s are surprisingly rare in daily life anyway.

Somehow, we’re afraid of fifties, presumably on the assumption that counterfeiters favour the biggest notes because they offer the biggest return on, ahem, investment.

In fact, you regularly see signs in shop windows, especially in tourist towns, saying, “Sorry, no £50 notes accepted.” (Yes, they are allowed to do that – you can’t force a shopkeeper to take your money, just as they can’t stop you spending it somewhere friendlier instead.)

The answer is: the £50 currently has a double-bill of engineers-stroke-entrepreneurs on the back, namely Matthew Boulton and James Watt.

Boulton and Watt were business parters who helped fire up the industrial revolution in Britain and elsehere by selling and licensing their steam engines around the world.

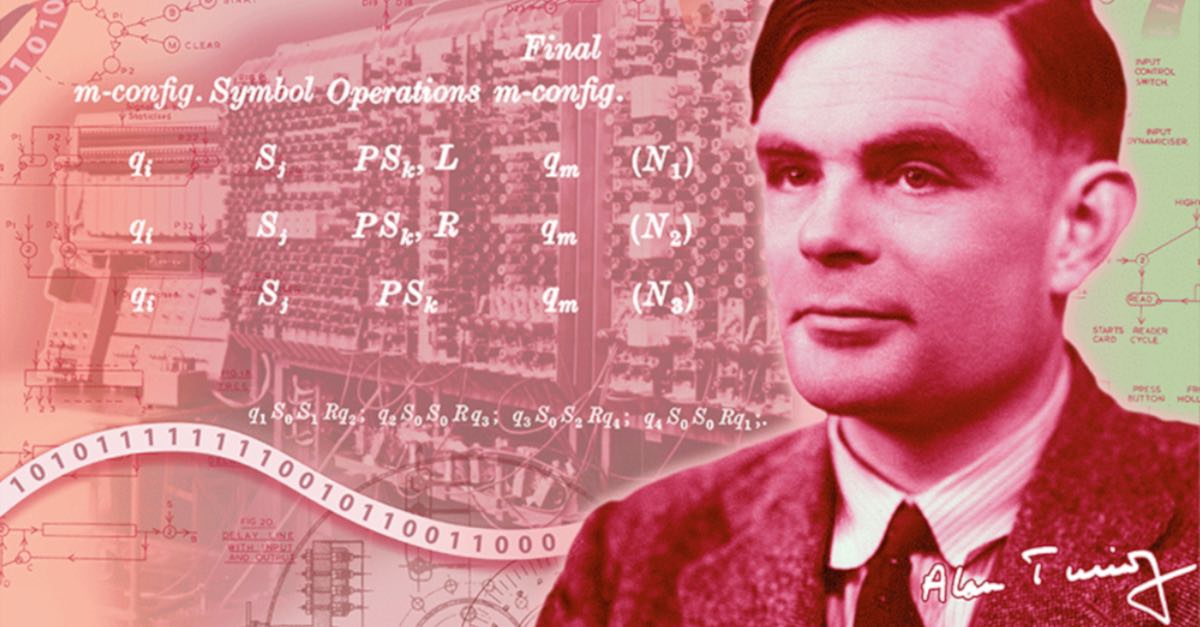

And when the new note comes out it will stick with STEM (that’s contemporary shorthand for science, technology, engineering and mathematics) because Alan Turing has been picked as the new face of the £50.

Our hero

We’ve written about Alan Turing many times on Naked Security – he’s quite a hero of ours for lots of good reasons that anyone interested in computer science will know.

He’s probably best remembered for his codebreaking work at Bletchley Park during World War 2, where Turing and many other brilliant minds worked in dreadful conditions so that the Allies could crack the Nazis’ encrypted messages and thereby acquire a critical operational advantage in the fight to depose Hitler and his abominable regime.

Bletchley was cramped, crowded, leaky, insanitary – and, for the women who ran the first-ever electronic digital computers that were installed there towards the end of the war, downright dangerous.

Apparently, the operators were instructed to wear Wellington boots on duty so that they wouldn’t be electrocuted as they tended to the Colossus computers while splashing about in standing water that had got in through the roof.

Physical and intellectual endurance

Turing’s physical and intellectual endurance during the war was astonishing – he carried on making cryptanalytical breakthroughs in the midst of such shortages of everything, including food and sleep and time, that most of us would simply have run out of steam and achieved nothing.

But in our view, the most amazing indication of his brilliance, both practical and theoretical, was his pre-war work in which he figured out various vital limits to “what digital computers can do“…

… before digital computers even existed.

Turing was gay in an era when that was proscribed by law in Britain.

This ultimately led to his prosecution and conviction in court, to his formal ostracism by the Establishment – who had, of course, conveniently ignored the law when his wartime contribution was so desperately needed – and, tragically, to his ultimate suicide.

In a way, therefore, it almost seems inappropriate to commemorate Turing now on the very Bank of England note that many people shun for reasons they can’t really explain, based on fears of being ripped off that they can’t really justify.

On the other hand, the £50 is the biggest English banknote in circulation, in both size and value, so perhaps it is a fitting tribute for Turing after all – one that will remind us of the huge value of mathematicians and scientists who can blend theory and practice in ways that advance the world as a whole.

As the Bank of England’s website proclaims, “Think science and celebrate Alan Turing.”

IN CASE YOU WERE WONDERING…

- Mary Anning (1799-1847) – a self-taught palaeontologist known around the world for the fossil discoveries she made in her hometown of Lyme Regis.

- Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1902-1984) – whose research revolutionised our understanding of the universe’s smallest matter.

- Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) – who drove the discovery of DNA’s structure, a critical breakthrough in our understanding of the biology of life.

- Stephen Hawking (1942-2018) – who made outstanding contributions to our understanding of gravity, space and time.

- William (1738-1822) and Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) – a brother and sister astronomy team devoted to uncovering the secrets of the universe.

- Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994) – whose research using x-ray crystallography delivered ground-breaking discoveries which shaped modern science and helped save lives.

- Ada Lovelace (1815-1852) and Charles Babbage (1791-1871) – visionaries who imagined the computer age.

- James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) – who made discoveries which laid the foundations for technological innovations which have transformed our way of life.

- Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) – whose incredible talent for numbers helped transform modern mathematics.

- Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) – who uncovered the properties of radiation, revealed the secrets of the atom and laid the foundations for nuclear physics.

- Frederick Sanger (1918-2013) – whose pioneering research laid the foundations for our understanding of genetics.

- Alan Turing (1912-1954) – whose work on early computers, code-breaking achievements and visionary ideas about machine intelligence made him one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE…

Featured image of Turing cropped from Bank of England 50-pound-note-nominations web page.

Ralph Hartwell

If there were enough room on the banknote, I would choose all of them. How can you pick just one from such an incredible list of talented people who have changed our world immensely?

But, if I were forced to choose just one, it would be Srinivasa Ramanujan. Because, in science, and everything else, if the numbers say it is so, then that’s the truth.

Paul Ducklin

When I first read Ramanujan’s story as a young adult, I was amazed and disillusioned in equal measure – the disillusion didn’t last long, but you can’t help but feel inadequate when you realise that Ramaujan never really *learned* anything… he figured it all out for himself. Basically, all of it. When I pondered all the mathematics I didn’t know *even after being taught it and passing examinations by reciting it back correctly later*… there was lot of a humblification going on there for me! If Ramanujan were commemorated on the £2 coin it would say, “Standing on the shoulders of, well, just sitting by myself, to tell the truth.”

Adam James

The digits in binary also represent Turing’s DOB in Binary format – 23 06 1912 – A very nice touch

Laurence Marks

> “Most people, at least in the UK itself, have no idea who’s commemorated on the fifty, ”

That’s odd. Although you don’t see $100 notes too often in the US (and many shopkeepers do decline to accept them), everyone knows that the portrait is that of Benjamin Franklin. In fact, the notes are colloquiallly called “Benjamins”.

Paul Ducklin

The portraits here typically change every time there’s a new note issue – even Her Majesty’s likeness gets updated (so does her image on the front of the coinage).

So the notes aren’t named after any person who was ever on them (and the portraits were only added comparatively recently, IIRC as an anti-counterfeiting measure).

roleary

All legal fifties since decimalization have had portraits on the back. I think you’re right that it’s down to individual portraits not running long enough to enter the public mindset. Plus not really being cultural icons in most cases. What did John Houblon do that can compare to playing with lightning?

Paul Ducklin

By “comparatively recently” I meant “in about the last 50 years”. US $100s have had Franklin continuously for more than a century.

Also, don’t know if it makes a difference, but Franklin is on the *front* of the note, like HM the Queen is here. I wonder how many Americans could say who is pictured on the *back* of a $100?

(Trick question, IIRC it’s a “what”.)

Intriguing that in the US, banknotes are called bills, meaning that bills are what you spend, while in Commonwealth countries, bills are what you pay. (For example, we might ask a waiter to bring the bill at the end of a meal but an American would ask for the check.)

Bryan

Here in the US (at least the western states), the terms bill and check are reasonably interchangeable at a restaurant–in full defiance of the fact that decades ago one could pay the bill with a check.

And to ensure we’ve thoroughly disoriented just about everyone, we sometimes call it a ticket (which also names a small scrap of paper granting access to a train, theater, or carnival ride) or a tab (which earlier helped open the beer you’re now trying to pay for).

TURN IT AROUND (SPOILER ALERT)

I incorrectly guessed the US Capitol would grace the $100 note,† but that’s on the $50. Independence Hall adorns the hundred,†† which I find rather appropriate for Señor Franklin.

† We don’t call them “notes” colloquially–but we must be perpetually hungry, because they’re often dough, bread, lettuce, cabbage, salad, clams (ew), biscuits, bacon, and cheddar.

†† before asking for a loan, know that I had to do a web search

This article was linked from one today, so I’m resurrecting an ancient conversation–16 months is enough time for spoilers too

:,)

Paul Ducklin

In British English, I think that if the context were clearly that of a paper banknote, we would understand the word “bill” to mean “a US banknote in particular”. We certainly understand “check” in the context of “restaurant invoice”, though would just say “bill”, and would expect it to be spelled “check”, which handily differentiates it from a “cheque” for payment (from the word Exchequer), which acquired the -que over here as a sort of French affectation.

Several US spellings have arrived and stuck over here, but only for specific meanings of a word. This can be rather useful: a dialogue is a chat you have with a real person but a dialog is a window your computer pops up. A program is a computer app but a programme is the schedule of events at a theatre or a show on TV.

Bryan

That’s pretty handy stuff to know.

Not sure we have many of those–all I can think of is disc/disk:

disc – as in CD or DVD

disk – as in floppy

And they’re both useful for only us dinosaurs who can recall them anyway.

…a sort of French affectation

In Britain, I’m given to understand there’s rarely concern this may be confused with French affection. Even the mild-mannered Rowan Atkinson included an entire nation in his skit depicting Satan as he greets new guests.

:,)

Paul Ducklin

English went through a series of crazy adaptations and spelling shifts over the years, some due to conquest and some due to influences of courtly language, science, religion, the Renaissance and European literature. The Anglo Saxons took some words from Celtic languages and from Vulgar Latin, then came the Danes and they changed a few words, thus some of the Germanic words in our language are Old Norse and not Old German, which is why we say “I took the parcel” and not “I neemed the parcel”, as we used to in the olden days. Then came the Normans, with their own weird sort of French, then we had the Angevins and Plantagenets, then “Paris French” became the cultured thing to speak, then there was a revival of interest in taking words from classical Latin, and all through this time there were regular efforts to retrofit the visual flavour of the era onto existing words, so that words *looked* cool when written down, even if the modifications didn’t match the way the words were spoken. And then, suddenly, we got dictionaries and people started agreeing that maybe we should fix the way we spelled and wrote – before that, spelling rules didn’t really exist. And that is why English pronunciation is such a mess, because the spelling often has little direct connection with the way we speak, and not just because our accents have changed. Some of our spelling changes happened for reasons that are little better than trendiness. (If you have ever wondered why the English word “det”, which means a sum of money you owe, ended up spelled “debt”, it was so educated people could demonstrate that we got it from the Latin word “debitum”, even though we had already adopted it as “det”, and we didn’t have the “-b-” or the -itum” parts. So to keep up with fashion you had to learn to write the word in an illogically new way, yet to say it aloud as you always had.)

Anyway, to foreigners who find English hard because there are just so many different words for the same thing, borrowed or injected from all over the linguistic world, and because seeing a word written down often gives you no idea at all how to say it…

…you are not alone. It’s a pain for native English speakers, too.