You’ve probably heard of metadata, which is a fancy name for “data about data.”

For example, a list of the phone calls you’ve made lately, and how long they lasted, but not what you said during the call.

Or a list of the filenames on your hard disk, along with how big they are and when you last edited them, but not what’s inside any of the files.

As you can imagine, metadata is gold dust to law enforcement during a criminal investigation: it can help with chronology; it can establish connections amongst a group of suspects; it can confirm or break alibis; and much more.

But metadata doesn’t feel like quite as much of a privacy invasion as full-blooded surveillance, so many countries tolerate collecting and using it on much more liberal terms than collecting the data itself, such as the actual contents of your files, or transcripts of your phone calls.

Of course, metadata is just as golden to social engineers – crooks who try to trick you into giving away information you’d usually keep to yourself by seeming to know “just enough” about you, your activities and your lifestyle.

Traffic analysis

Crunching through metadata to do with network connections is usually called traffic analysis, and you might be surprised how much it gives away, even when the traffic itself is strongly encrypted.

Here’s an intriguing example from a bevy of security researchers in Israel, who eavesdropped on encrypted web traffic (on their own network, of course).

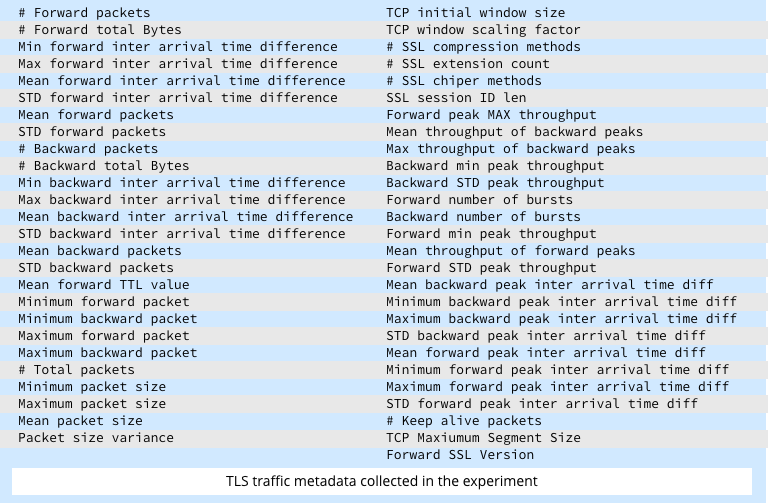

They monitored a range of measurements about the TLS traffic that passed by, even though they couldn’t monitor anything inside the packets:

Using various machine learning techniques, they claim to have been able to classify their packet captures to make surprisingly insightful estimates of which combination of operating system, browser and web service were in play.

For example, they could guess fairly reliably that “this user was watching YouTube using Safari on OS X,” while “that user was using Twitter from Internet Explorer on Windows.”

That might not sound like a terribly important or worrying result, but remember that TLS encryption is supposed to provide confidentiality.

In other words, anything that leaks out about what’s inside a TLS-protected data stream is information that an eavesdropper isn’t supposed to be able to figure out.

What to do?

If you’re a programmer, you can take precautions against this sort of attack by introducing what you might call “deliberate inefficiencies”.

For example, by inserting random and redundant noise into your traffic, such as variable delays and additional random data, you can disguise patterns that might otherwise stand out.

In the case of this research, however, there’s no need to panic.

Not yet, anyway.

The classifications that the researchers were able to perform so far were very broad indeed, and sometimes not at all certain.

After all, “Internet Explorer on Windows” is a good guess for most TLS traffic, and you can figure out which traffic is going to Twitter by looking at the packet destinations alone.

Nevertheless, this is a handy reminder that the argument “it’s harmless to collect metadata in bulk because it isn’t the actual data itself” is fundamentally flawed.

Image of metadata through the magnifying glass courtesy of Shutterstock.

Anonymous

I was doing some research into encrypted Voice of IP connections recently (basically when you use the Internet to talk to someone like a phone call). That also sends quite a bit in the clear. You wouldn’t know what the call was about, but you’d know how long it lasted, the kinds of codecs used (such as if the call includes video), and with a little work, you might be able to determine that one side spoke for 20 seconds, and the other side spoke for 15 seconds, and so on.

rhkennerly (@rhkennerly)

The encryption debate only muddies the water. The government has all the damning information stored in the metadata of cell records anyway. I’ve been warning about the dangers of a collection of metadata warehoused out in Utah for years (or now warehoused by the carriers).

I spent an entire military career in SIGINT/ELINT. We did amazing work (well before computers) with the very simple signals of the time applying just a bit of brainpower & persistence. Modern cellphones and computers are a goldmine compared to what we had to work with, giving off all kinds of signals and storing all kinds of information.

Take your average citizen who intentionally “flies below the government’s radar” on gun ownership issues. Give me two cell towers that overlap a shooting range or a gun store and it is child’s play to identify all the cellphones at the range. From there it’s a simple matter of analysis to start identifying the owner’s friends, family, habits and patterns of life. Even if our subject doesn’t go to the range, he’s probably in contact with someone who does.

Even the lack of a signal is telling (just ask Osama Bin Laden). Consider two phones that power down at about the same time during the day when they near a motel. Those are pretty good signs of a sexual encounter. It certainly gives prying eyes an idea where & when to look and who to look at.

The real danger of metadata is it’s historical nature, however. Consider the San Bernardino shootings. By backtracking the signals and patterns from those phones regular citizens could be called on to justify their movements in the past. Did they and the shooter just happen to grab coffee at the same Starbucks 5 days a week at about the same time, or did the two of you intentionally meet?

On TV Cop shows they’re always saying “there are no coincidences.” That is false. The harder you look, the deeper you dig, the more coincidences you find. In the wrong hands innocent coincidences become damning evidence. Having to justify your movements months or years after the fact is a terrible burden to place on citizens. That’s the reason local law enforcement are obtaining Stingray technology.

We used to say that they fed would drown in all the data, but parallel computing and HADOOP chained servers and the right software makes sorting through all the metadata already stored child’s play.

The danger is in the patterns, not the content.

Anonymous

THIS IS GOOD …!!!!