When you buy a new device, especially for use at home, you probably want to unpack it, connect it up and start using it as quickly as possible.

It’s not like the 1980s, when to play a game on your cool new home computer you first had to type in hundreds of lines of BASIC programming without making any serious mistakes, then debug what you’d typed in, then lose it all when the computer crashed, then type it in all over again more carefully…

Whether it’s your trendy internet kettle, a new security camera or a fancy “digital doorbell,” you’re probably looking for a plug-and-play experience.

Device vendors typically take one of three approaches:

- Ignore security altogether, so the default security settings are “no security at all.” If the device does have security built in, you have to set it up later, after connecting it up for the first time.

- Preconfigure some one-size-fits-all settings and print them in the manual. Everyone starts from the same place, but you can tighten things up later.

- Choose random security settings for each device and print them on a card that’s stuck underneath or included in the box. Ideally you will tighten things up later, but if you don’t, you’re still better off than in case (1) or (2).

Of course, case (3) is the trickiest for a vendor, because it means that each device has to be customised, digitally and physically, with a unique configuration file installed in the firmware, and a matching sticker or card printed and included in the package.

Nevertheless, case (3) is the best of the lot, because it means you have some security – such as passwords that can’t simply be searched out on Bing or Google – at the outset.

It’s especially handy for a home Wi-Fi router, where a globally-predictable default configuration might expose your whole network to easy attack, even if only for a short period while you were setting it up.

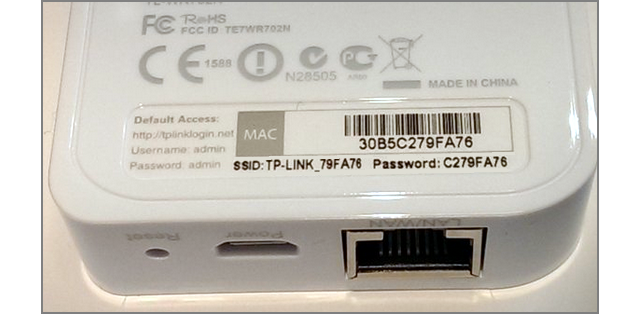

We don’t normally recommend writing down your passwords and keeping them in an obvious place, but sticking the default password on the underside of a Wi-Fi router isn’t a bad idea.

A crook would have to break into your house and turn over your router just to get the password, rather than hanging around across the road and guessing your password from a distance:

At least, that’s the theory.

Unfortunately, a password that’s unique isn’t necessarily unpredictable or hard to guess, even if it looks complicated.

In the example above, first publicised on Twitter at the end of 2015, router vendor TP-LINK has gone to the trouble of printing a one-off label for each router it shipped…

…yet it hasn’t really done any better than case (1) above.

Here’s why.

Both the network name and the Wi-Fi password are directly (and very obviously) derived from the MAC.

And the MAC address (officially short for Medium Access Code, but often called the Media Access Code), although unique, is not meant to be a secret.

In fact, it’s deliberately and purposefully broadcast in every Wi-Fi packet from the router, precisely because it is unique and thus won’t accidentally clash with any other network devices nearby.

In other words, anyone with a Wi-Fi sniffing tool such as Kismet or Wireshark can figure out your MAC address, and that’s by design.

Therefore, if you have a TP-LINK router of the sort pictured above, and you haven’t changed the defaults, anyone can guess – in fact, they can precisely compute – both your network name and your password, as soon as they see your MAC address.

It gets worse, of course, because they don’t even need a network sniffer.

They can just ask their laptop to show nearby networks, and when one called TP-LINK_AABBCC shows up, they know six of the eight characters in the default password, which will be ??AABBCC.

After just 256 guesses for the value of the hex digits denoted by ??, they’re certain to get in if you are still using the defaults.

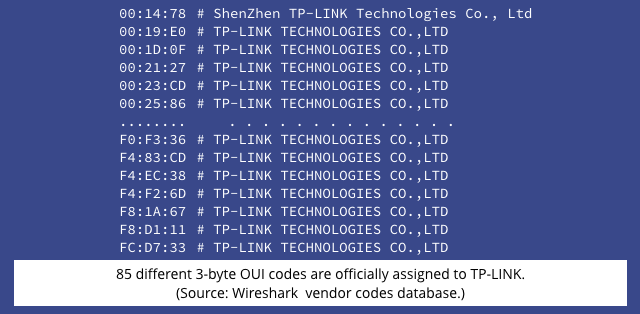

Actually, it’s worse than that, because the first three bytes of every MAC address is the OUI, or Organisationally Unique Identifier, issued to the vendor of the device in advance.

(Two hex digits make up one byte, so three bytes are represented by six hex digits.)

Sophos’s wireless access points, for example, all start with 00-1A-8C, which denotes Sophos Limited. This simplifies the issuing process, like pre-allocating number plates starting MZ to the city of Mainz in Germany, or WI to Wiesbaden on the other side of the Rhine.

TP-LINK is a big enough vendor that it has not one but 85 OUIs allocated to it, but those have only 70 different values in the their third byte:

That reduces the number of Wi-Fi password guesses to 70 once you’ve seen that TP-LINK_ prefix.

By the way, many routers offer an option called “network hiding” or “SSID hiding,” where your network doesn’t show up in the list that nearby phones or laptops will display.

But hiding your network name doesn’t help in this case: it’s a safety feature that stops people connecting to you by mistake, not a security measure that stops them connecting altogether.

That’s because your Wi-Fi network reveals its name in any packets sent and received by devices that have already connected, making your network name a matter of public record anyway.

Even if the network name were a secret, your access point’s MAC address reveals the vendor, thanks to the OUI in first three bytes. That’s why sniffers like Wireshark and Kismet can show in real time the vendors of the network devices they’ve captured – it’s a simple lookup in the OUI table. So an attacker could guess when to try TPLINK_ at the start of the network name, whether it was known or not.

WHAT TO DO?

- Change the default passwords on any device you connect to your network. Change them before you connect it for the first time if you can, or as soon as possible thereafter if you can’t.

- Brush up on wireless security with our popular Wireless Security Myths video. Tricks like MAC address filtering and network name hiding do not provide any meaningful security – make sure you understand why.

Here’s that video:

Cool Wi-Fi mosaic image courtesy of Shutterstock.

GS

Not to sound too paranoid but it does sound as if we’re (general) pushing towards Biometrics even for Routers which would be a very good way of achieving a fingerprint database without arresting anyone.

On a lighter note, if the Biometrics were to come into play at that level then you would have to blend the ‘Touch The Banana’ blog into this. LOL

jilkka

There should be have been a picture of a minion below the text in that :)

qqq

Biometrics is a terrible authentication method because password cannot be changed and once your hands / eyes / etc. are photograph your whole virtual life is ruined for the rest of your life.

mattccs

For the sake of clarity, you should explain that the first 3 bytes of the MAC are actually its first 6 hex digits. Therefore, the last byte of the OUI (hex digits 5 and 6) correspond to hex digits 5 and 6 of the MAC. That was lost on me initially.

Paul Ducklin

Good idea. I’ll make that clear.

Dr H. Gonzalez-Velez

For the record: MAC stands for Medium Access Control (See IEEE. Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications. IEEE

Standard 802.11, 2012. http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11-2012.pdf ). Otherwise this is a good reminder of the risks of default settings.

Paul Ducklin

The term “media access control” is very widely used, to the point that “medium access control” sounds pretty weird :-) I think that in regular use, “media” (like “data”) has pretty much become a singular noun, so I’d consider it unexceptionable, even if it’s not strictly correct by the book.

So I think I’ll leave the article to call it “media access control” (many devices support multiple media, after all) as the common name, and let your comment remind everyone what you should write if you want to be official and precise.

(Most people just call it “MAC”, not even considering it an acronym :-)

Stoat

It’s simpler than that, because you can already see the MAC.

So in the case above, where you can see TP-LINK_AABBCC on MAC XXYYZZAABBCC, it’s a fair bet that the password is ZZAABBCC

Paul Ducklin

Ah, that’s why we wrote “if you have a TP-LINK router of the sort pictured above, and you haven’t changed the defaults, anyone can guess – in fact, they can precisely compute – both your network name and your password, as soon as they see your MAC address.”

The point of the “70 guesses” is that you don’t even need the MAC if your laptop has listed the network name, making this doubly bad. Everyone knows how to produce a network list, because your Wi-Fi connection manager does it for you, no special software required. Not everyone knows how to list the MACs visible in the ether.

(In short: don’t use MACs as a shared secret, but don’t use network names as a part of your shared secret either.)

Stoat

WIFi radar and many other apps int he Android store aimed at measuring signal strength also show MACs.

Using Wireshark or Kismet is “sledgehammer to crack a nut” territory.

Paul Ducklin

Not really. A sledgehammer smashes a nut into fragments and isn’t actually suitable for the task.

Using Wireshark or Kismet to sniff Wi-Fi packets is perfectly reasonable IMO, even though both products can do a lot more than that.

Think of it like using Firefox to download a file, even though cURL could do the job instead.

My 2p.