Here at Naked Security, we have a variety of views about password managers.

Generally speaking, we’re in favour, because password managers are tools that generate and store a list of different, hard-to-guess passwords for all your websites and online accounts.

That means that if you’re the kind of person who has hundreds of passwords, or who struggles to memorise even a few wackily long and mixed-up passwords, or both, password managers can be a huge help.

With a password manager, you don’t end up with repetitious and guessable passwords like mikenyt, mikeicloud and mikegmail for your New York Times, Apple and Google accounts respectively.

Instead, the password manager makes up phrases like OLr9Ia7iJZgt, mz8mE;Vbnf4DVtm0 and JDYUG=mzGrSW.8j.

Better yet, it enters those passwords for you into the right web pages, so there’s no extra hassle caused by typing in weird-and-wacky text.

And a password manager can stop you putting real login data into a fake web page, because it simply doesn’t have a password to match a bogus site such as phishygmail.example.

The downside of password managers

There’s one non-trivial downside that you need to keep in mind: the password manager’s vault, whether it’s stored online or offline, is typically protected by a password of its own.

That password can’t be kept inside the vault, because you’d need to know the password anyway to get into the vault to retrieve the password.

So the master password needs to be remembered and stored in more traditional ways.

And if a crook gets hold of your master password, then that’s like getting the crown jewels – because now the crook has access to all your accounts at once.

LastPass breached

It was therefore with some trepidation that we read a just-published security notice from popular password manager LastPass, saying that the company had found crooks inside its network.

LastPass lets you store your password vault online, so it needs some way of validating, over the network, that you know your master password.

That means it has some sort of authentication database for all its users.

And the LastPass authentication database is, apparently, one of the things that the crooks got into.

That means, amongst other things, that the crooks very likely have your email address, your password hint, and a representation of your password.

That’s the bad news.

Not all bad

But here’s the good news.

It doesn’t look as though the crooks got anything of importance more than the authentication data (e.g. no encrypted user data was accessed).

And LastPass does a good job of storing its password representations – your passwords are salted, hashed and stretched, and only ever stored in that scrambled, irreversible form.

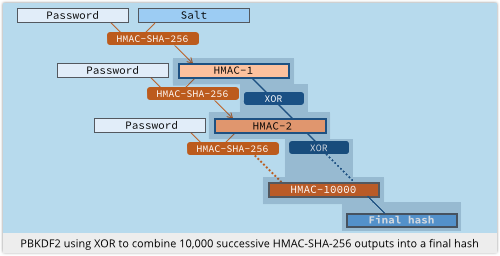

→ Salting is where you add some random nonsense to the actual password text. So even if two users pick the same password, their password representations end up different. Hashing is where you scramble the salted password cryptographically and store the one-way scrambled version only. Stretching is where you deliberately re-run the hashing part over and over again before storing the representation, to slow an attacker down.

In November 2013, we proposed the following for storing your customers’ passwords safely:

- A process called PBKDF2 to mangle your real password into a storable representation.

- A hash called HMAC-SHA-256 as the hashing function inside PBKDF2.

- At least 10,000 iterations of the hash function for “stretching” (time-consumption) purposes.

It turns out that LastPass does just what we recommended!

Actually, it exceeds our minimum suggestion, because it uses HMAC-SHA-256 for 100,000 iterations, not just 10,000.

So, even though LastPass’s breach is a rather bad look for the company, it’s unlikely that a crook who has your password hash will be able to work through enough guesses to chance upon it any time soon – provided that you picked a proper password in the first place.

And remember that the crook only has from now until you head over to LastPass and change your master password.

Once you update your password, the old hashed representation is useless, because it no longer represents the new password.

What to do?

So we’ll echo LastPass’s advice:

- Change your LastPass password as soon as you can, making the password data stolen by the crooks of historical interest only.

- If you used the same password anywhere else, change those passwords too, and don’t share passwords again.

- Consider using two-factor authentication, where you need your password and an additional login code that changes every time.

Remember that your LastPass master password is the key to your whole castle, yet it is also a password (perhaps the only password) you need to memorise.

So it’s worth knowing a few tricks on how to pick a proper password:

→ Can’t view the video on this page? Watch directly from YouTube. Can’t hear the audio? Click on the Captions icon for closed captions.