Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Take Control of Every Threat

Sophos unites unmatched threat intelligence, adaptive AI, and human expertise in an open platform to stop attacks before they strike — giving you the clarity and confidence to stay ahead of every threat.

SOPHOS CISO ADVANTAGE

CISO-level Expertise, For All

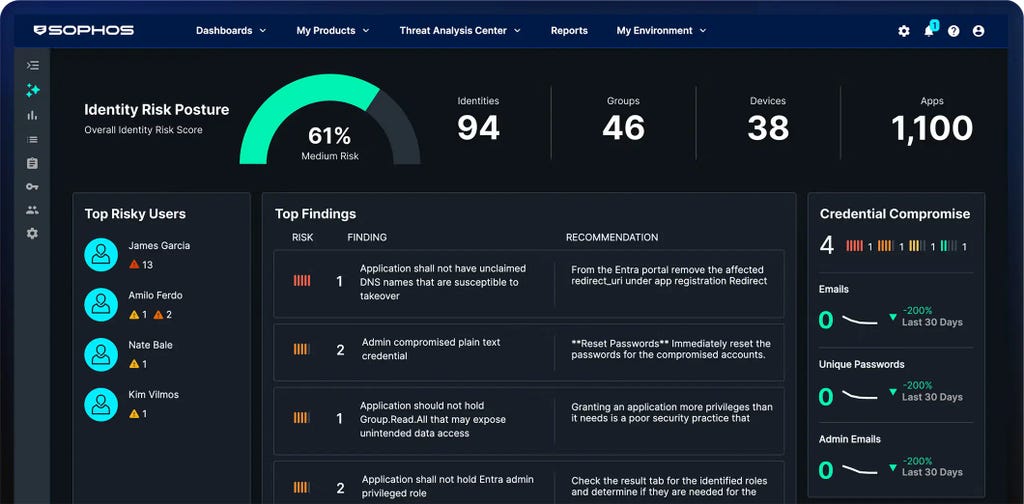

Sophos acquires Arco Cyber to deliver continuous control validation and risk assurance at scale.

ARCO CYBER

Sophos Acquires Arco Cyber

Helping organizations move from assumption to proof for superior cybersecurity outcomes

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 now available

Sophos Firewall v22 takes Secure by Design to a whole new level

Adaptive AI-Native Cybersecurity Platform

Take Control of Every Threat

Sophos unites unmatched threat intelligence, adaptive AI, and human expertise in an open platform to stop attacks before they strike — giving you the clarity and confidence to stay ahead of every threat.

SOPHOS CISO ADVANTAGE

CISO-level Expertise, For All

Sophos acquires Arco Cyber to deliver continuous control validation and risk assurance at scale.

ARCO CYBER

Sophos Acquires Arco Cyber

Helping organizations move from assumption to proof for superior cybersecurity outcomes

Sophos Firewall

Sophos Firewall v22 now available

Sophos Firewall v22 takes Secure by Design to a whole new level

Defeat cyberattacks

World-class technology and real-world expertise, always in sync, always in your corner. That’s a win, win.

Resilient protection and an adaptive AI-native platform to stop attacks before they strike

Elite MDR threat hunters to find and defeat threats with precision and speed

Unparalleled defense for the entire attack surface – endpoint, firewall, email, and cloud

Leading security professionals recommend Sophos

.webp?width=120&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=440&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp?width=360&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Stop threats before

they strike

With Sophos, AI evolves with threats and experts never miss a move, so you can grow with confidence. See how we protect your business.

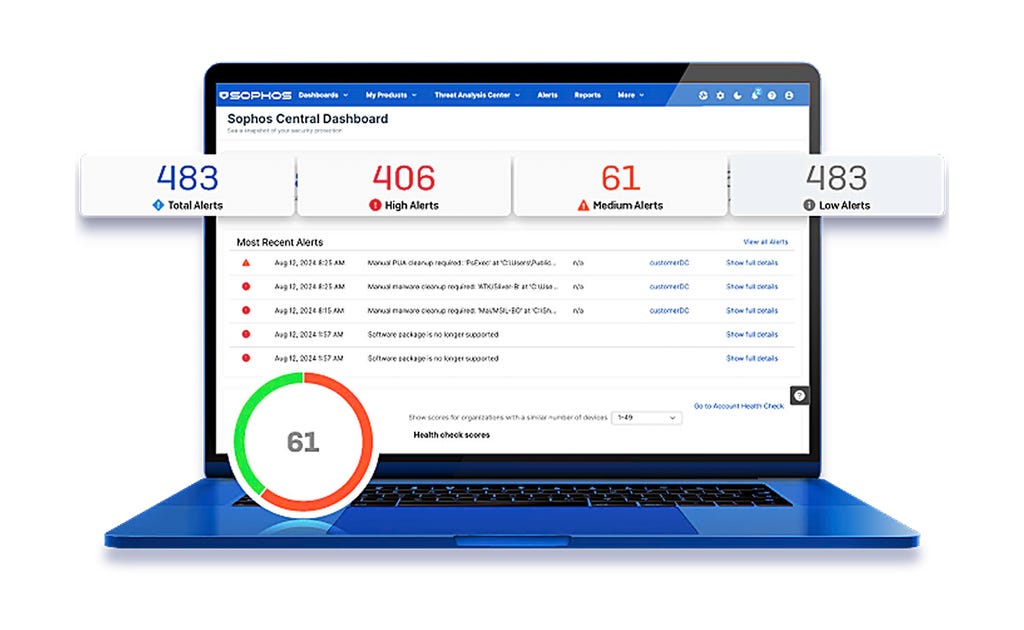

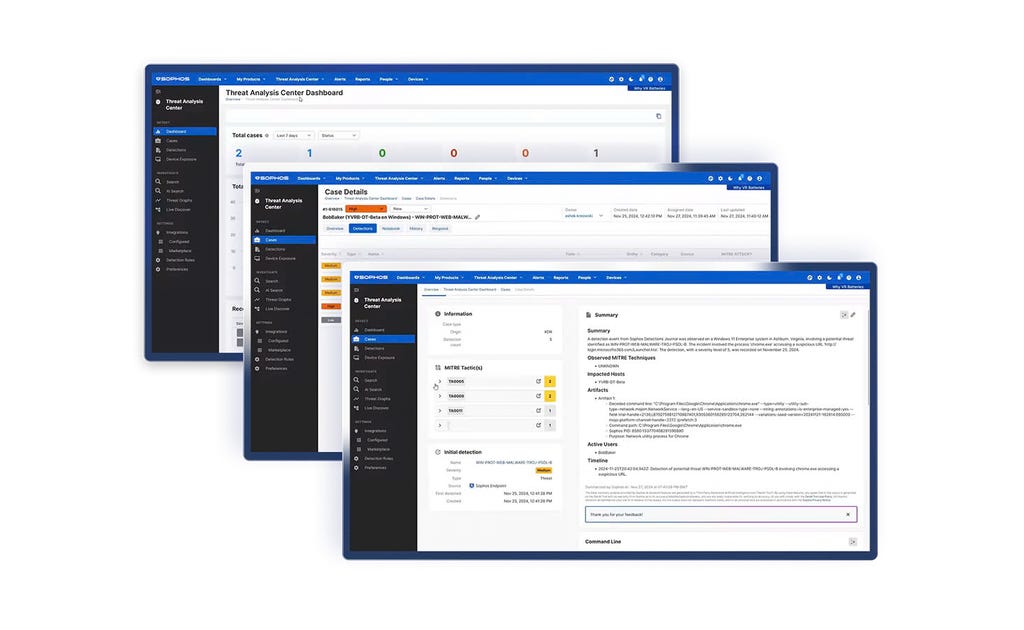

Adaptive AI-native cybersecurity platform

Sophos Central delivers unrivalled protection for customers and enhances the power of defenders. Dynamic defenses, battle-proven AI, and an open, integration-rich ecosystem come together in the largest AI-native platform in the industry.

Sophos has you covered

Solutions to your security challenges

How businesses

stay secure with Sophos

.webp?width=980&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

Sophos X-Ops

Bringing together deep expertise across the attack environment to defend against even the most advanced adversaries.

Events and training

Join us for live and on-demand global opportunities to hear from our subject-matter experts. Access our training to build the skills and knowledge needed to defeat cyberattacks.

.svg?width=185&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.svg?width=13&quality=80&format=auto&cache=true&immutable=true&cache-control=max-age%3D31536000)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)

.webp&w=1920&q=75)