The latest high-profile cybercrime exploits attributed to the Clop ransomware crew aren’t your traditional sort of ransomware attacks (if “traditional” is the right word for an extortion mechanism that goes back only to 1989).

Conventional ransomware attacks are where your files get scrambled, your business gets totally derailed, and a message appears telling you that a decryption key for your data is available…

…for what is typically an eye-watering amount of money.

Criminal evolution

As you can imagine, given that ransomware goes back to the days before everyone had internet access (and when those who were online had data transfer speeds measured not in gigabits or even megabits per second, but often merely in kilobits), the idea of scrambling your files where they lay was a dastardly trick to save time.

The criminals ended up with complete control over your data, without needing to upload everything first and then overwrite the original files on disk.

Better yet for the crooks, they could go after hundreds, thousands or even millions of computers at once, and they didn’t need to keep hold of all your data in the hope of “selling it back” to you. (Before cloud storage became a consumer service, disk space for backup was expensive, and couldn’t easily be acquired on demand in an instant.)

Victims of file-encrypting ransomware ironically end up acting as unwilling prison wardens of their own data.

Their files are left temptingly within reach, often with their original filenames (albeit with an extra extension such as .locked added on the end to rub salt into the wound), but utterly unintelligible to the apps that would usually open them.

But in today’s cloud computing world, cyberattacks where ransomware crooks actually take copies of all, or at least many, of your vital files are not only technically possible, they’re commonplace.

Just to be clear, in many, if not most, cases, the attackers scramble your local files too, because they can.

After all, scrambling files on thousands of computers simultaneously is generally much faster than uploading them all to the cloud.

Local storage devices typically provide a data bandwidth of several gigabits per second per drive per computer, whereas many corporate networks have an internet connection of a few hundred megabits per second, or even less, shared between everyone.

Scrambling all your files on all your laptops and servers across all of your networks means that the attackers can blackmail you on the basis of bankrupting your business if you can’t recover your backups in time.

(Today’s ransomware crooks often go out of their way to destroy as much of your backed-up data as they can find before they do the file scrambling part.)

The first layer of blackmail says, “Pay up and we’ll give you the decryption keys you need to reconstruct all your files right where they are on each computer, so even if you have slow, partial or no backups, you’ll be up and running again soon; refuse to pay and your business operations will stay right where they are, dead in the water.”

At the same time, even if the crooks only have time to steal some of your most interesting files from some of your most interesting computers, they nevertheless get a second sword of Damocles to hold over your head.

That second layer of blackmail goes along the lines of, “Pay up and we promise to delete the stolen data; refuse to pay and we won’t merely hold onto it, we’ll go wild with it.”

The crooks typically threaten to sell your trophy data on to other criminals, to forward it to the regulators and the media in your country, or simply to publish it openly online for anyone and everyone to download and gorge on.

Forget the encryption

In some cyberextortion attacks, criminals who have already stolen your data either skip the file scrambling part, or aren’t able to pull it off.

In that case, victims end up getting blackmailed only on the basis of keeping the crooks quiet, not of getting their files back to get their business running again.

That seems to be what happened in the recent high-profile MOVEit attacks, where the Clop gang, or their affiliates, knew about an exploitable zero-day vulnerability in software known as MOVEit…

…that just happens to be all about uploading, managing, and securely sharing corporate data, including a component that lets users access the system using nothing more complex than their web browsers.

Unfortunately, the zero-day hole existed in MOVEit’s web-based code, so that anyone who had activated web-based access inadvertently exposed their corporate file databases to remotely-injected SQL commands.

Apparently, more than 130 companies are now suspected to have had data stolen before the MOVEit zero-day was discovered and patched.

Many of the victims appear to be employees whose payroll details were breached and stolen – not because their own employer was a MOVEit customer, but because their employer’s outsourced payroll processor was, and their data was stolen from that provider’s payroll database.

Furthermore, it seems that at least some of the organisations hacked in this way (whether directly via their own MOVEit setup, or indirectly via one of their service providers) were US public service bodies.

Reward up for grabs

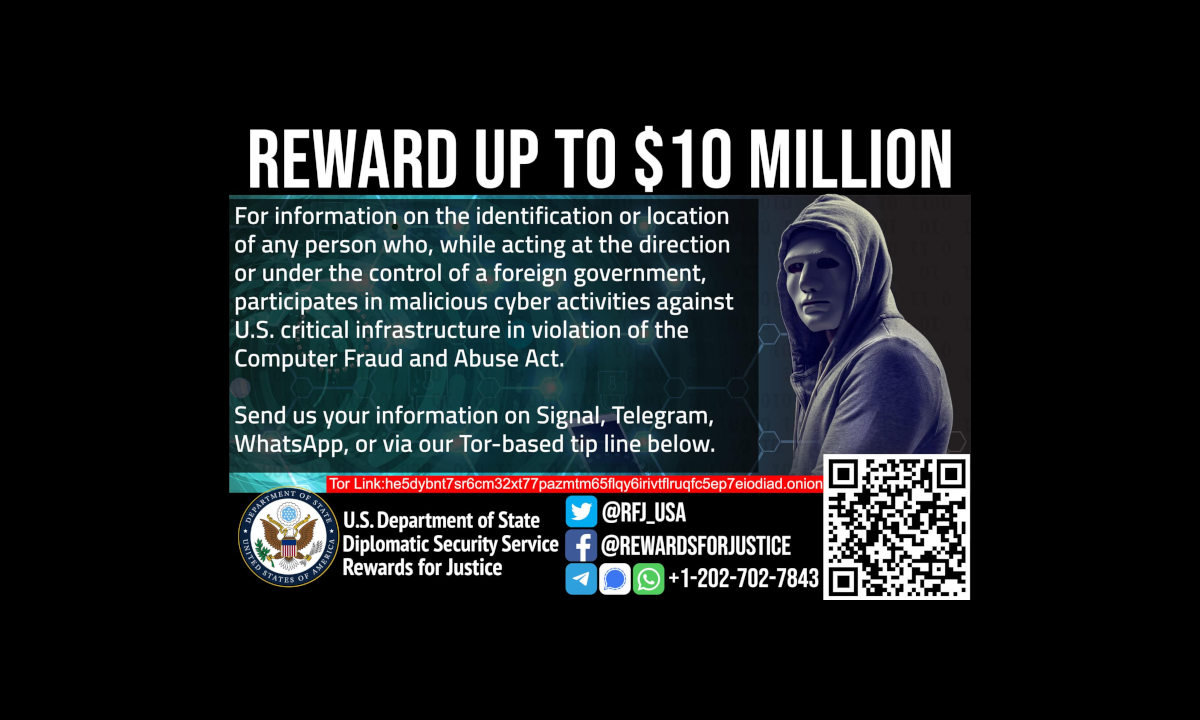

This combination of circumstances led to the US Rewards for Justice (RFJ) team, part of the US Department of State (your country’s equivalent might go by the name Foreign Affairs or Foreign Ministry), reminding everyone on Twitter as follows:

Advisory from @CISAgov, @FBI: https://t.co/jenKUZRZwt

Do you have info linking CL0P Ransomware Gang or any other malicious cyber actors targeting U.S. critical infrastructure to a foreign government?

Send us a tip. You could be eligible for a reward.#StopRansomware pic.twitter.com/fAAeBXgcWA

— Rewards for Justice (@RFJ_USA) June 16, 2023

The RFJ’s own website says, as quoted in the tweet above:

Rewards for Justice is offering a reward of up to $10 million for information leading to the identification or location of any person who, while acting at the direction or under the control of a foreign government, participates in malicious cyber activities against US critical infrastructure in violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

Whether informers could end up with several multiples of $10,000,000 if they identify multiple offenders isn’t clear, and each reward is specified as “up to” $10 million rather than an undiluted $10 million every time…

…but it will be interesting to see if anyone decides to try to claim the money.

Adam

It sounds like the reward is purposely designed to encourage the CLOP (or is it CL0P?) members to turn on each other, and/or for friends/family members/acquaintances to turn them in.

After all, $10 million is quite a lot of money, no matter what currency you convert it into.

Paul Ducklin

Ransomware gangs do have some history of falling out with each other, such as:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2021/08/06/conti-ransomware-affiliate-goes-rogue-leaks-company-data/

And, perhaps, in this particular bust:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2023/01/27/hive-ransomware-servers-shut-down-at-last-says-fbi/

Anonymous

I would be surprised if they would pay at all.