The success of “pig butchering” (sha zhu pan, 杀猪盘) scams has driven the expansion of their hunt for new victims, both by well-established and well-organized scam rings and by smaller and less professional copycats. In the fake gold trading scam I discussed in my last report, for example, initial contact of victims was made through Twitter. Others we’ve seen have used Facebook Messenger for their initial approach, or other social media and messaging apps. And several others I’ve encountered—including the one detailed in this report—have reached out with a lure message over Apple’s iMessage or other digital channels for Short Message Service (SMS) texts.

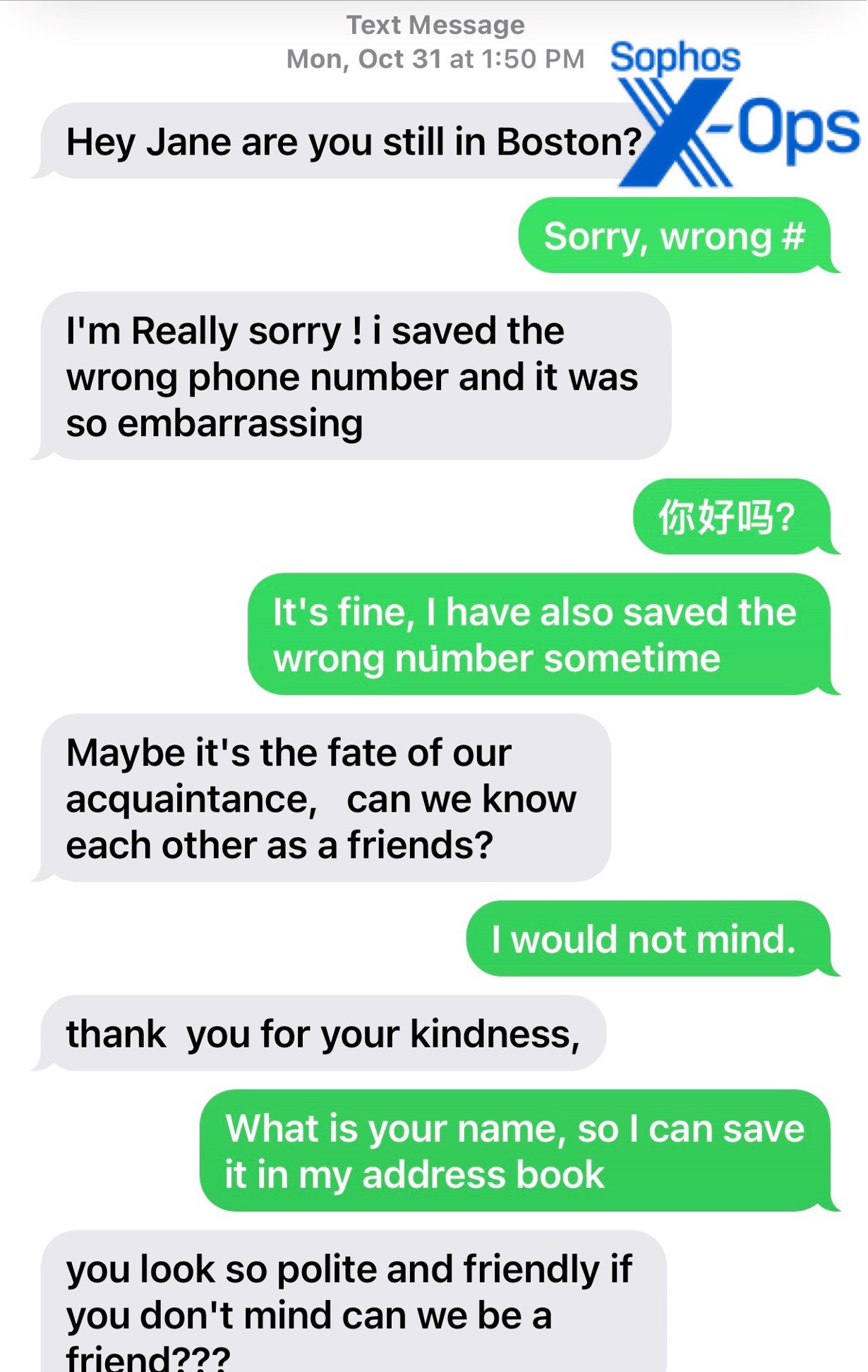

These texts, which are usually designed to look like accidental mis-texts, are really designed to allow the scammers to spam large numbers of potential victims and then selectively engage those who text back. From there, they attempt to engage in casual conversation, and then suggest that the digital meet-cute is a sign that they are “fated to be friends.” From there, the scam follows a familiar pattern—moving the target to another messaging platform for easier engagement while freeing up the text account to approach additional victims or be shut down while another number is set up.

As I discussed in our previous report, I received a deliberately mis-addressed text message on one of my phones that led me into an engagement with the scam ring (which I have designated as “Sour Grapes” for reasons that will soon become apparent), with a young Malaysian woman acting as the face of the scam and occasionally directly interacting with me.

From the data I was able to gather during the interaction, I determined that the ring she was working for had gathered over $3 million US in cryptocurrency over a 5-month period—and that it was one of hundreds of nearly identical scam operations using similar lures and nearly identical websites and apps. While we were unable to gather full wallet data associated with these other fake trading and liquidity mining apps, we assume the overall take of this ring is much larger.

As we were preparing this report, my colleague Jagadeesh Chandaraiah got a message from an individual in the US who had received an almost identical set of communications—only in his case, the woman was Vietnamese, and the scam was focused on “contract mining”—another name for liquidity mining. We uncovered a number of fake decentralized finance apps purporting to be for liquidity mining among the other sites using similar domains and infrastructure to the Sour Grapes scam.

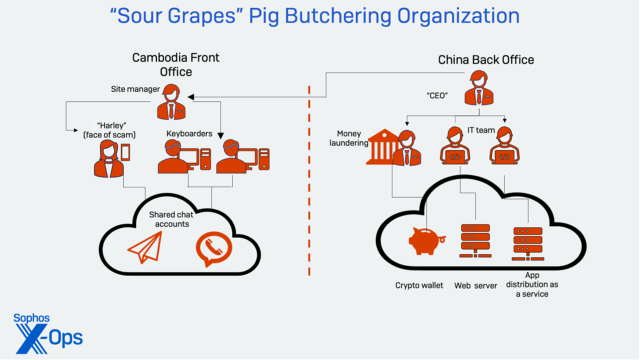

This type of lure is particularly popular with Chinese organized crime operations working out of countries in Southeast Asia. Several of these operations have been identified by previous reporting as being based in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Cambodia (where this scam’s human operations were based), Myanmar, Laos, and other countries.

The teams running these scams include a young man or woman acting as the face of the scam, keyboarders who keep the victim engaged, and a team generating and repurposing media content to help fill the message exchanges with targets with fabricated proof of their backstory. They may also abuse mapping services to make it appear their persona is where and who they claim to be.

It is the long duration and complexity of the communications these scam rings engage in that makes them particularly convincing to even some more skeptical targets. In this case, the scammers made first contact with me on October 31, and messaged me multiple times a day all the way through December to get me to enroll in their fraudulent cryptocurrency trading scheme. During that period, I was able to identify much of their infrastructure, including wallet addresses and web resources used by the scheme and fake applications for both iOS and Android, and share them with other organizations; twice, the scammers were forced to change wallet addresses, and they had to change domains for their websites while still trying to convince me of their legitimacy.

Several things stood out about this group. First, it was clear that the group had taken pains to build a somewhat credible backstory for their persona, on the level we have seen from Facebook-based scams. The woman who was the face of the scam was actively involved in it, and made several video calls to ensure that I was going to take the bait. And while not as sophisticated as some of the other groups we’ve encountered from a technical perspective, the scammers were able to quickly respond to takedowns of their infrastructure.

But it was also clear that multiple people were involved in maintaining contact with me, and had limited knowledge of operational security techniques or even the culture of the country they were claiming to live in. If these organizations start learning how to create more consistent, locale-specific technology footprints—and do more thorough coaching of their front-line texting operatives—then these scams could become much more convincing and catch even more victims with their lures. Education on the scope of these scams remains the best defense against them.

All trick, no treat

On October 31, I received a random text message on one of my phones: “Hi Jane are you still in Boston?”

That was the first message I received from “Harley,” the persona associated with this scam attempt. The message came from a number associated with Sinch Voice, a Sweden-based VoIP provider, linked to a Louisiana phone number. “Harley” claimed be in Vancouver, British Columbia.

As with the previous “pig butchering” scam I detailed, I was honest about my line of work: I told Harley that I worked in cybersecurity. This did not seem to matter as much as my age and whether I was alone. I provided the answers the scammers wanted to hear (over 50, living alone), and Harley eagerly continued the conversation, sending a photo of herself standing next to an elaborate bar. As I would learn from later video interaction, the person in the photo was an active member of the scam team as well as its face.

Later photoanalysis and research revealed that this was a photo from a hotel bar in Phnom Penh.

The written English in the texts was clumsy in places, and probably run through computer translation in places – as in when the person behind the texts asked, “do you sing telegram?” when they were trying to move the conversation over to that messaging service. The Telegram account used by “Harley” was associated with a number from a UK mobile carrier (EE Ltd.).

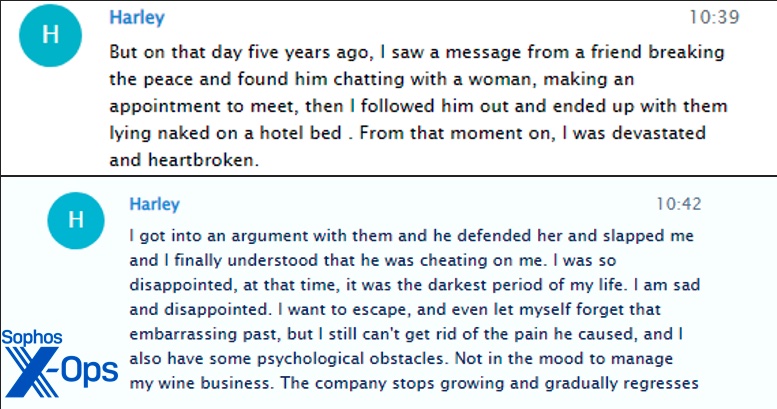

While this detail was shared with the previous scam I researched, there was a significant difference in the interactions once we got to Telegram. Harley came with a very rich backstory: she claimed to run a wine business in Vancouver (giving the name of a specific British Columbia winery), and said that her family was originally from Malaysia. She also set up an emotional appeal, telling of how her husband, who used her father’s help to start his own “wine factory,” cheated on her and left her while she was pregnant with their child. This included a story of how she got a hotel employee to give her a key to the room he was meeting his mistress in:

Figure 4: Part of Harley’s backstory.

Figure 4: Part of Harley’s backstory.

Harley added that the business had struggled because of COVID-19. And of course, she was able to rescue her wine business with the help of her aunt, who taught her how to make money trading cryptocurrency.

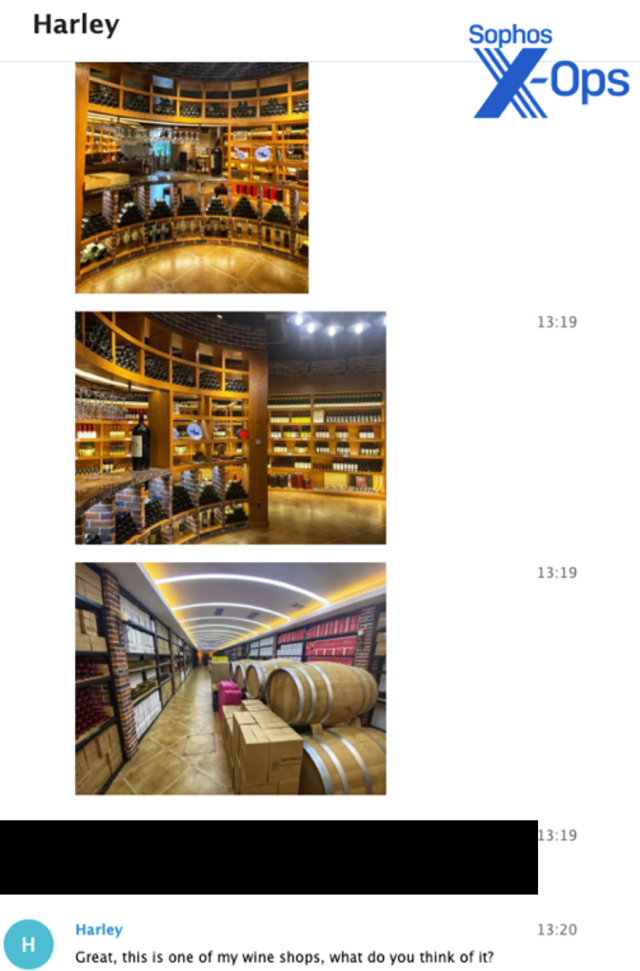

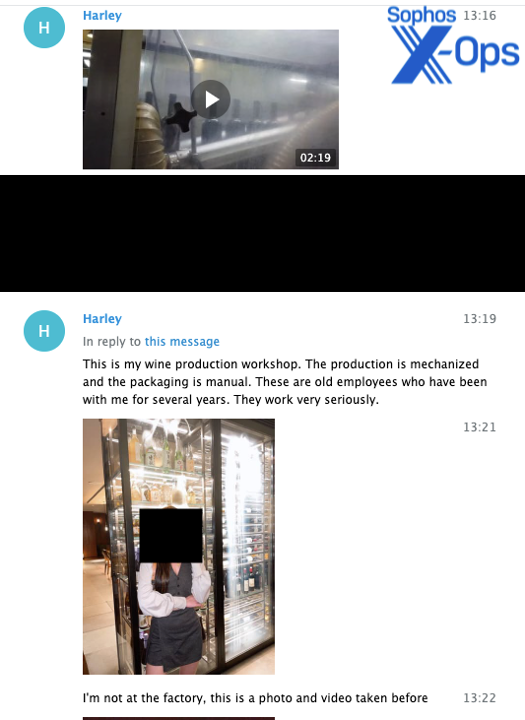

Harley (or the keyboarders operating on her behalf) also sent additional photos of cases of wine, videos of bottling operations, and other content intended to establish Harley as being in the “grape factory” business. The photos, when analyzed carefully, told a different story, of course; the cases of wine she claimed were from her vineyard and the bottles on the line in her “grape factory” were marked with the name of a French winery, and not the name of the winery she claimed to be connected to.

There was some effort made to give this story a modicum of credibility. She gave the name of an actual British Columbia-based winery as her business, and a search for the store location she had given me resulted in a hit on Apple Maps—a user-contributed location which, when checked with Google Street View, turned out to be a local office for the VoIP provider Telus. The location is marked by Apple as “permanently closed” now.

Harley claimed to have two of these shops in Vancouver and said she was planning to open one in New York, “but my business is costing me a lot of money because of COVID-19, About $1 million, but I recovered a lot by investing in cryptocurrencies and early real estate.”

And thus crypto began to work its way into the conversation.

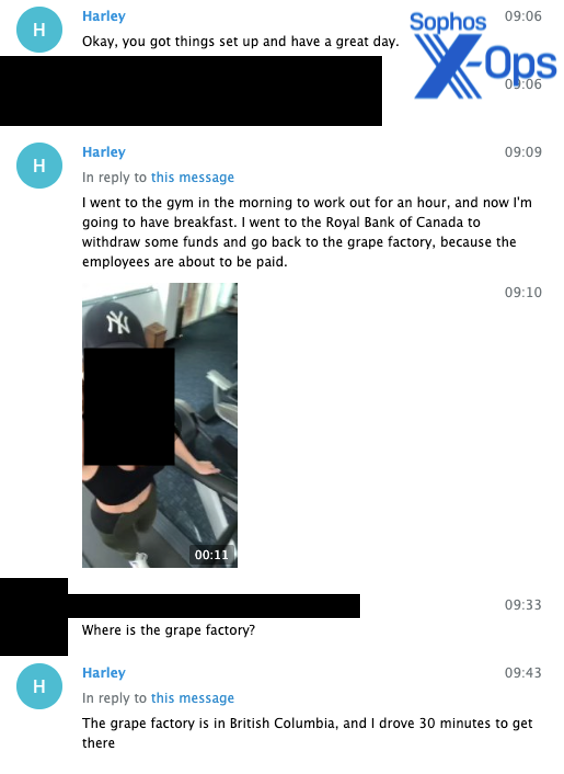

The next day, the person behind Harley’s keyboard told me she was headed out to pay employees at “the grape factory.” A video of Harley on a treadmill holding up her phone for a selfie and saying “I’m working out” was supplied to validate her claim of hitting the gym.

I asked her to send pictures, hoping for exterior shots of her claimed winery (or “grape factory”), but instead she sent a video taken from a French winery’s website of a bottling line in operation, the labels of the bottles plainly visible. Then she added a photo from inside her “workshop,” showing her in front of a glass storage case filled with bottles with Chinese labels.

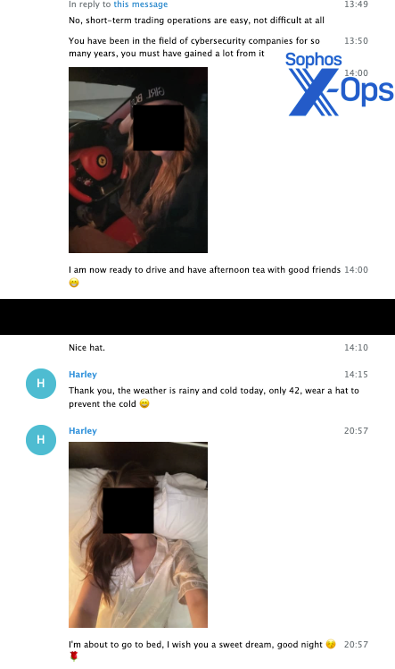

There were also frequent hints at how well she was doing now: photos of her shopping hauls, of food she was preparing or had purchased, and of the cars she claimed to own (including a Ferrari).

The Ferrari and other cars, along with photos of food and expensive consumer products, would be a major portion of the conversation over the next month. Harley also expounded on other personal matters, including how fragile she was emotionally because of her recent abandonment by her husband, and how her child with her ex-husband was being raised by her parents.

By two weeks in, Harley was going deep into her fictional backstory of betrayal, retreat from the world, and eventual redemption through crypto trading under the guidance of her aunt. She also told me how I (her target) was her only male friend and confidante. “So I hope that every day in the future we can cherish everything and cherish each other! keep our friendship alive,” she typed.

An invitation to visit came, as well as an invitation to spend time with her at her “villa” in Miami.

But there were never any pictures of Harley outside. Other than the videos and photos sent showing her exercising, shopping, or getting into the Ferrari, all the photos of Harley were in the same room with paneling and acoustic tiles with no other features visible, or at a desk in what appeared to be a hotel business center or conference room. The gym photos appeared to be from a hotel workout room.

The long chatting period was punctuated, of course, with comments about how she was making huge profits on short-term crypto trades.

Trying to close the deal

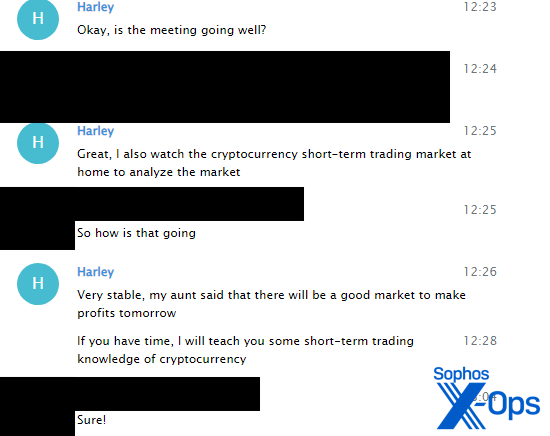

After nearly a month of this, I decided to accelerate the process, and mentioned to Harley that I was curious about how she was making so much money. Harley said her aunt had taught her to do this, and that she could share the same market intelligence her aunt apparently gave her.

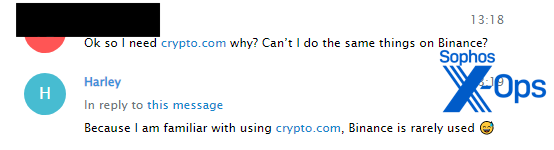

First, she said, I needed to buy some cryptocurrency with a Crypto.com wallet. This scam specifically targeted Crypto.com, with Coinbase as a backup; they explicitly avoided the market giant Binance.

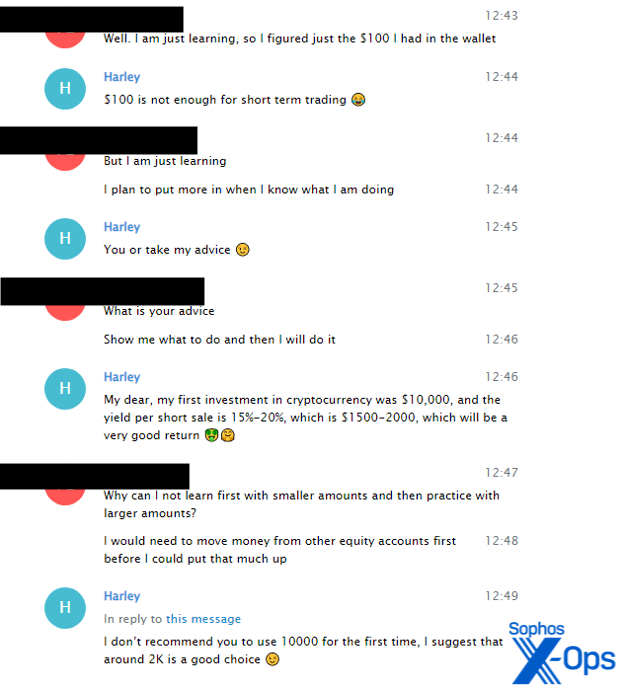

To get started, Harley told me I needed at least $2000 USD:

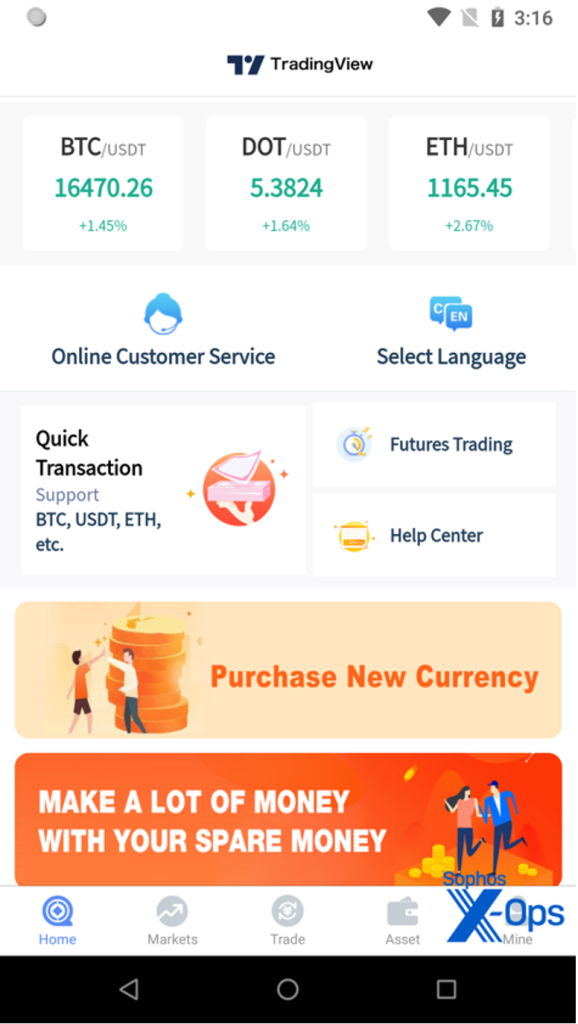

I balked at this, and held off furthering the “lesson” until after Thanksgiving. However, I asked her if there were any other apps I needed, and she directed me to a download link to install apps—either an Android application or a “Webclip” for iOS with a provisioning profile. Both used the logo and name of TradingView, the market charting app provider.

From the web clip provisioning profile, I harvested the website being used to front the iOS version of the fake app. From the US, it resolved to an Amazon Web Services Cloudfront host. Passive DNS records also resolved the domain to a host in Hong Kong.

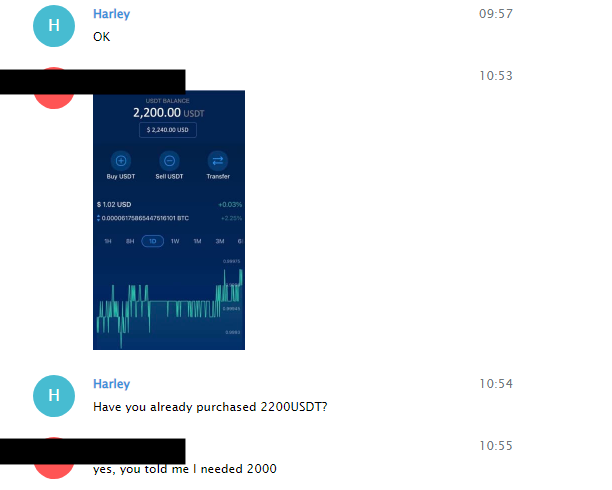

To make sure I was actually going to pony up the $2000 worth of Tether cryptocurrency (USTD, a “stablecoin” closely pegged to the US dollar) that Harley suggested I needed for “learning,” she wanted to walk me through screenshots of the purchase. She also made a video call to me to make sure I was going to do it. I fabricated a screenshot of a Crypto.com wallet with 2,200 USDT in it to provide (from one with a balance of $2), and sent it along.

The app

Harley gave me a link to download an app for the next step (hxxps://www[.]tdvies[.]com/download) . She followed up with instructions on how to deposit funds. Since it was the Thanksgiving holiday, I applied the brakes a bit again on moving forward—and began to do some technical analysis.

The download site, purporting to be for an app from the trade charting software provider TradingView, had two buttons. The first was for an Android .APK file hosted on another site (hxxp://app[.]tdviewdn[.]vip). The second, for iOS, downloaded a mobile profile file for installing a “web clip” application pointing to yet another site (hxxps://www[.]ksjbfs[.]vip).

Figure 16. The mobile profile downloaded by iOS to install the scammer’s web clip.

Figure 17 The URL serving up the web clip.

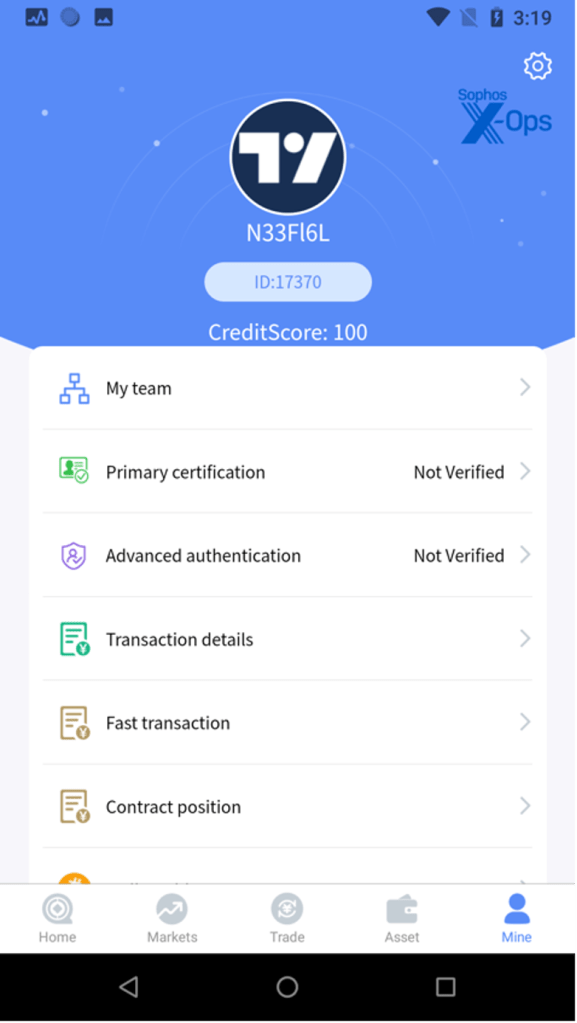

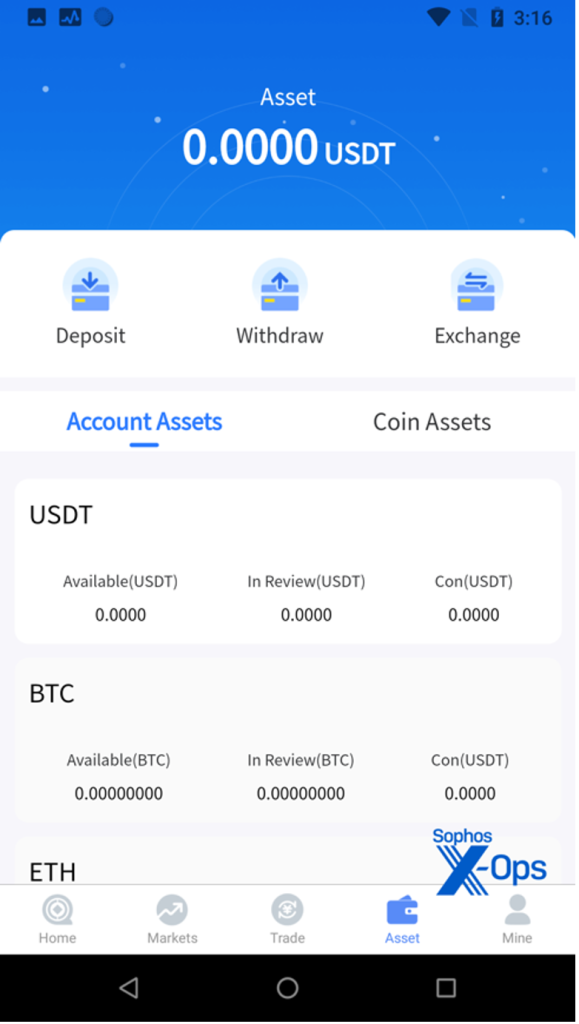

The Android app and the web clip both functioned identically; they were tied to the same backend, so a username and password set on one worked on the other. The Android app made web calls to another site (hxxps://www[.]gefwts[.]vip), which provided a set of web service hooks.

From the app, I was able to get the wallets used for “deposit” of assets (both USDT and BTC wallets were listed). I was also able to pivot off the web sites themselves to identify similar web and Android apps on the same and other hosts. Other apps I found guarded against non-targeted individuals from gaining access to wallet data by requiring an invitation code to register.

So far, I’ve found more than 500 additional domains associated with the same basic kit. The fake exchange (and in some cases, fake decentralized finance staking) sites hijacked a variety of crypto-trading brand names:

A list of these domains, as well as the wallets associated with some of the apps, is provided as part of the indicators of compromise file posted to our GitHub page.

A majority of these sites were hosted through Amazon Web Services’ CloudFront service provided through a reseller; others were hosted through Cloudflare, and many also resolved to a Hong Kong-based hosting service. Almost all of the domains were registered through Namecheap.

A full list is in the indicators of compromise file posted to the SophosLabs GitHub. We have shared the domain list with AWS and Cloudflare, and are continuing to gather additional domains linked to the software kits used by these scam operations.

All of the apps and websites were coded by Chinese-speaking programmers. The Android apps use a push update library written by a Hunan-based developer who goes by the moniker “SunSeeker X,” and other artifacts and the backing infrastructure indicate these websites and apps are maintained by a China-based IT team.

I shared the first set of wallets I had found with the crypto tracking company Chainalysis and with crypto exchange threat researchers, and the domains associated with the app with AWS. Shortly afterward, they went dead. I asked Harley what was going on, as the app did not work; I was given new links to the apps, which had new wallets. I repeated this process.

The first set of wallets had taken in $102,839 worth of Tether and $247,251 worth of Bitcoin; these wallets were active until January, when they were cashed out. A second USDT wallet, also cashed out and inactive since January, took in $118,871. The most recent USDT wallet has received $1,892,610.31 as of February 15; the most recent Bitcoin wallet address has received $608,213 worth of BTC.

That is over $3 million over a five-month period from a single scam operation. In the case of the largest wallet, we identified inbound Tether transactions from 57 wallet addresses; of these, the majority came from Crypto.com wallets or from private wallets that had been filled from Crypto.com (as they had in the other, less active wallets).

According to analysis by Jacquiline Koven of Chainalysis, the scammers moved crypto deposited in the wallets to the Tokenlon exchange, which has recently been used to launder a large volume of “pig butchering” scam funds.

Where’s Harley?

As I continued to drag my feet on pulling the trigger on “investing.” I received a video call over Telegram from Harley. She was standing in front of a beige, sound-proofed wall, and all she really wanted to talk to me about was whether I was going to follow through and deposit crypto. There were several voice call follow-ups from her. The person in the video call was the woman in the photos that had been sent to me, but it was clear from her English language skills that she was not the only one sending me texts; her English was not consistent with the “grape factory” level malapropisms of some of the daily messages I received.

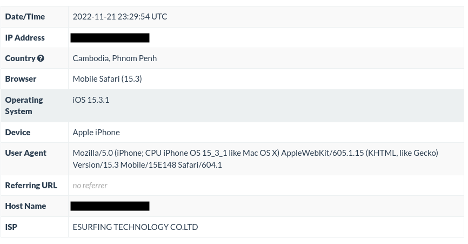

I dropped a news story about “pig butchering” operations in Cambodia wrapped in a tracking link into a conversation about my concerns. That link was opened 5 times—first on an iPhone on one network, and then on four different Windows 10 desktops on another. Both networks, fronted by MicroTik routers, were provided by the same Phnom Penh-based ISP. Based on further refinement, the Windows computers appeared to be in the beach resort town of Sihanoukville, a known center of Chinese pig slaughtering operations.

To see how the team behind Harley would react, I said that I would be traveling to Vancouver for work and wanted to meet them in person. They agreed and promised to meet with me. A few days later I told them that I was at the address of Sophos’ office in Vancouver.

They then accused me of trying to scam them. Communications were cut off, and our chat was deleted (but not before I archived it).

Conclusions

During my investigation of this particular ring, a target of a similar scam reached out to us. His story almost exactly mirrored my experience with a few exceptions—the woman claimed to be Vietnamese and in New York running a makeup business, and she wanted him to use Crypto.com to join a “contract mining” scheme (a fake decentralized finance operation based on “liquidity mining” like the one I investigated last year). I found a number of fake liquidity mining sites using the same style app distribution and web application frameworks as the fake trading sites I had uncovered, leading me to believe with confidence that this was another operation affiliated with the same Chinese “back office” supporting the “grape factory” crew, suggesting a very large-scale overall operation with many social engineering franchises providing the flow of victims.

The nature of these operations has been well-documented elsewhere—in some cases, the people behind the keyboards are not there of their own volition and were lured by fake employment ads for high-paying jobs. Others are willing participants and are paid well for their performances in comparison to what they could earn in the local economy.

Regardless of how they are recruited, these keyboarders are part of an industrialized scam operation that is willing to invest hundreds of hours in conversation with victims in order to steer them toward investment and then extract all the value they can from them. They have refined emotional manipulation to a science. And their operational security skills are improving as they attract greater scrutiny.

In the long term, the best defense against these scams (as with all cyber scam operations) remains public education—the infrastructure is too fluid, and the tactics used by these operations are being adapted by cybercriminal rings around the world. Each time one set of infrastructure was identified and targeted, the scammers would simply switch on a new one; this may have caused minor disruption to their cash flow from victims, but it is evident from the wallet transactions tracked that they still were able to rake in millions.

Law enforcement and threat research collaboration can increase the cost of running these scams, and perhaps with time disrupt the financial operations behind them, but a lack of international cooperation on cybercrime will continue to give the people behind these rings a safe harbor to operate from.

Sophos X-Ops would like to thank Jagadeesh Chandraiah of SophosLabs and Jacquiline Koven of Chainalysis for their contributions to this report, and the threat teams at Coinbase and Amazon Web Services for their assistance in blocking and taking down scam infrastructure.

E

I’ve been scammed recently with the same platform as in your post. I wish I had read this before the scam happened somehow.

Melinda

Wonderful article that documents and analyzes the steps of the scam. Thank you for pointing out the detail inconsistencies in “her” story and communication. The same basic outline is revised and re-used thousands upon thousands of times every day, always with a relative (uncle, esp.) who is an investment or crypto expert. I am involved in a project that is currently writing a book on the pig-butchering phenomenon, and all of it’s exhausting layers. Your expert reporting is spot-on and very wise. Thank you for sharing this story, so that others can see how very “not-unique” their own scam experiences might be. It’s so weird, it’s almost unbelievable–and that’s what the scammers hope will catch our attention. Thank you…

gallagherseanm

Thanks for your comment. Feel free to contact me if you need any other information from our research.

Tony Jack

I wished I had known the term pig butchering prior to it happening to me. I considered myself savvy to scams as I get the random text frequently. I know exactly what they want, however, the outfit that got me was refined in the art of manipulation. Their scheme is more elaborate and convincing.

Anyhow, I. am in contact with my state Attorney General and the Secret Service. I have saved the wallet address provided and have traced it as hundreds of thousands if not millions have run through it.

In retrospect, I realize how fake it all was. From announcing to the platform that you had deposited USDT into your account. Now I know I never had control of my money once it was sent to their address, they needed me to tell them so they could put the phony amount on the website with the appearance of legitimacy.

Pete C

Interesting. I engaged a wrong-number scammer (starting as an SMS then transferring to Line) over the last couple of days, and the backstory was almost identical to this one – wine business almost failed because of the pandemic but saved by her aunt. One of the pictures of the wine business they sent got a reverse image search match to a Chinese guy’s FB page. After about 2 days of chatting fairly inconsequentially, I asked “her” for a video chat. She came up with a lame excuse why she couldn’t. I feigned being ticked off and suspicious of her, but today I just decided to let them know that I knew they’re a pig butcher from the first message, sent them a few choice paragraphs about what I think of them and their ilk. All but the last one was read, so I assume they’ve blocked me now.

David True

Thank you very much for this article which I found through a recent article in the Seattle Times. My experience is eerily similar with a Crypto Romance scam initiated through Facebook almost 12 months ago and eventually directing me into investing money through Crypto.com and then transferring into an account at www.myth-market.com. I was convinced to increase my initial investment of $2000 up to $12000. The options trading showed this increased in value to $35K. However, when I requested a withdrawal of $10K the site required me to deposit an additional $9899 to “verify” my account. I refused this and my account is now locked. I am interested in finding out if the MythMarket is on the list of bogus Crypto currency trading platforms.