Thanks to Tommy Mysk and Talal Haj Bakry of @mysk_co for the impetus and information behind this article. The duo describe themselves as “two iOS developers and occasional security researchers on two continents.” In other words, although cybersecurity isn’t their core business, they’re doing what we wish all programmers would do: not taking application or operating system security features for granted, but keeping their own eyes on how those features work in real life, in order to avoid tripping over other people’s mistakes and assumptions.

The featured image above is based on one of their tweets, which you can see in full below.

Twitter recently announced that it doesn’t think SMS-based two-factor authentication (2FA) is secure enough any more.

Ironically, as we explained last week, the very users for whom you’d think this change would be most important are the “top tier” Twitter users – those who pay for a Twitter Blue badge to give them more reach and to allow them to send longer tweets…

…but those pay-to-play users will be allowed to keep using text messages (SMSes) to receive their 2FA codes.

The rest of us need to switch over to a different sort of 2FA system within the next three weeks (before Friday 2023-03-17).

That means using an app that generates a secret “seeded” sequence of one-time codes, or using a hardware token, such as a Yubikey, that does the cryptographic part of proving your identity.

Hardware keys or app-based codes?

Hardware security keys cost about $100 each (we’re going by Yubikey’s approximate price for a device with biometric protection based on your fingerprint), or $50 if you’re willing to go for the less-secure sort that can be activated by the touch of anyone’s finger.

We’re therefore willing to assume that anyone who has already invested in a hardware security token will have done so on purpose, and won’t have bought one to leave it sitting idly around at home.

Those users will therefore already have switched away from from SMS-based or app-based 2FA.

But everyone else, we’re guessing, falls into one of three camps:

- Those who don’t use 2FA at all, because they consider it an unnecessary additional hassle when logging in.

- Those who turned on SMS-based 2FA, because it’s simple, easy to use, and works with any mobile phone.

- Those who went for app-based 2FA, because they were reluctant to hand over their phone number, or had already decided to move on from text-message 2FA.

If you’re in the second camp, we’re hoping you won’t just give up on 2FA and let it lapse on your Twitter account, but will switch to an app to generate those six-digit codes instead.

And if you’re in the first camp, we’re hoping that the publicity and debate around Twitter’s change (was it really done for security reasons, or simply to save money on sending so many SMSes?) will be the impetus you need to adopt 2FA yourself.

How to do app-based 2FA?

If you’re using an iPhone, the password manager built into iOS can generate 2FA codes for you, for as many websites as a you like, so you don’t need to install any additional software.

On Android, Google offers its own authenticator app, unsurprisingly called Google Authenticator, that you can get from Google Play.

Google’s add-on app does the job of generating the needed one-time login code sequences, just like Apple’s Settings > Passwords utility on iOS.

But we’re going to assume that at least some people, and possibly many, will perfectly reasonably have asked themselves, “What other authenticator apps are out there, so I don’t have to put all my cybersecurity eggs into Apple’s (or Google’s) basket?”

Many reputable companies (including Sophos, by the way, for both iOS and Android) provide free, trustworthy, authenticator utilities that will do exactly what you need, without any frills, fees or ads, if you understandably feel like using a 2FA app that doesn’t come from the same vendor as your operating system.

Indeed, you can find an extensive, and tempting, range of authenticators just by searching for Authenticator app in Google Play or the App Store.

Spoilt for choice

The problem is that there is an improbable, perhaps even imponderable, number of such apps, all apparently endorsed for quality by their acceptance into Apple’s and Google’s official “walled gardens”.

In fact, friends of Naked Security @mysk_co just emailed us to say that they’d gone looking for authenticator apps themselves, and were somewhere between startled and shocked at what they found.

Tommy Mysk, co-founder of @mysk_co, put it plainly and simply in an email:

We analysed several authenticator apps after Twitter had stopped the SMS method for 2FA. We saw many scam apps looking almost the same. They all trick users to take out a yearly subscription for $40/year. We caught four that have near identical binaries. We also caught one app that sends every scanned QR code to the developer’s Google analytics account.

As Tommy invites you to ask yourself, in a series of tweets he’s posted, how is even a well-informed user supposed to know that their top search result for “Authenticator app” may in fact be the very one to avoid at all costs?

Which authenticator app am I gonna go with? 🤔 pic.twitter.com/iO3y91D2Gp

— Mysk 🇨🇦🇩🇪 (@mysk_co) February 20, 2023

Imposter apps in this category, it seems, generally try to get you to pay them anywhere from $20 to $40 every year – about as much as it would cost to buy a reputable hardware 2FA token that would last for years and almost certainly be more secure:

Many of these suspicious authenticator apps use this technique to trick users. After you finish the welcome wizard after the first launch, you get the in-app purchase view. And the x button to dismiss the view appears after a few seconds (upper right corner)#AppStore pic.twitter.com/sgxEo5ZwF0

— Mysk 🇨🇦🇩🇪 (@mysk_co) February 20, 2023

When we tried searching on the App Store, for example, our top hit was an app with a description that bordered on the illiterate (we’re hoping that this level of unprofessionalism would put at least some people off right away), created by a company using the name of a well-known Chinese mobile phone brand.

Given the apparent poor quality of the app (though it had nevertheless made it into the App Store, don’t forget), our first thought was that we were looking at out-and-out company name infringement.

We were surprised that the presumed imposters had been able to acquire an Apple code signing certificate in a name we didn’t think they had the right to use.

We had to read the company name twice before we realised that one letter had been swapped for a lookalike character, and we were dealing with good old “typosquatting”, or what a lawyer might call passing off – deliberately picking a name that doesn’t literally match but is visually similar enough to mislead you at a glance.

When we searched on Google Play, the top hit was an app that @mysk_co had already tweeted about, warning that it not only demands money you don’t need to spend, but also steals the seeds or starting secrets of the accounts you set up for 2FA.

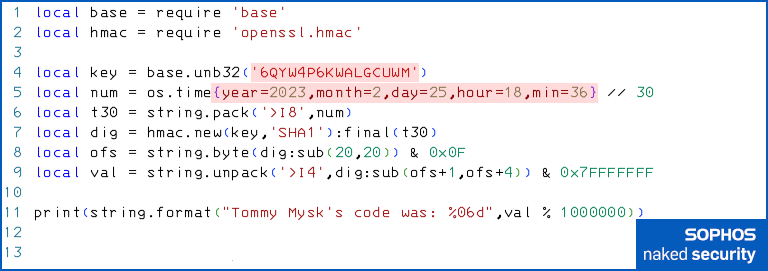

Remember the secret string 6QYW4P6KWALGCUWM in the QR code, and the TOTP numbers 660680 that you can see in the images below, because we’ll meet them again later on:

Just like its #iOS version, this #Android authenticator app sends scanned QR codes to a remote server. It has been downloaded 500K+ times. It's among the top 5 hits when you search for #2FA apps on @GooglePlay.

Spread the word and warn your friends✌️#Privacy pic.twitter.com/5qlbXGyu0R— Mysk 🇨🇦🇩🇪 (@mysk_co) February 25, 2023

Why seeds are secrets

To explain.

Most app-based 2FA codes rely on a cryptographic protocol known as TOTP, short for time-based one-time password, specified in RFC 6238.

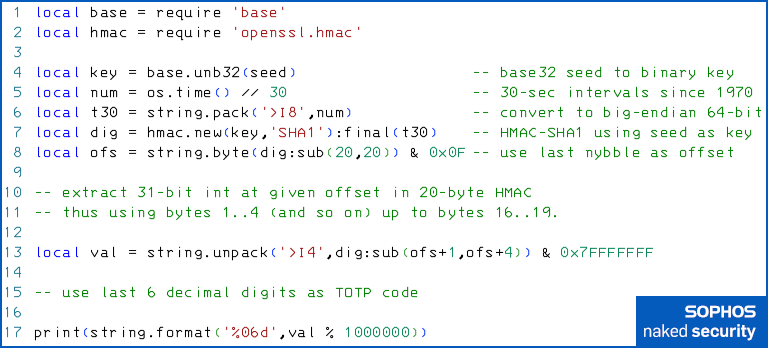

The algorithm is surprisingly simple, as you can see from the sample Lua code below:

The process works like this:

A. Convert the seed, or “starting secret”, originally provided to you as a base32-encoded string (as text or via a QR code), into a string of bytes [line 4].

B. Divide the current “Unix epoch time” in seconds by 30, ignoring the fractional part. The Unix time is the number of seconds since 1970-01-01T00:00:00Z [5].

C. Save this number, which is effectively a half-minute counter that started in 1970, into a memory buffer as a 64-bit (8-byte) big-endian unsigned integer [6].

D. Hash that 8-byte buffer using one iteration of HMAC-SHA1 with the base32-decoded starting seed as the key [7].

E. Extract the last byte of the 160-bit HMAC-SHA1 digest (byte 20 of 20), and then take its bottom four bits (the remainder when divided by 16) to get a number X between 0 and 15 inclusive [8].

F. Extract bytes X+1,X+2,X+3,X+4 from the hash, i.e. 32 bits drawn anywhere from the first four bytes (1..4) to the last-four-but-one bytes (16..19) [13].

G. Convert to a 32-bit big-endian unsigned integer and zero out the most significant bit, so it works cleanly whether it’s later treated as signed or unsigned [13].

H. Take the last 6 decimal digits of that integer (calculate the remainder when divided by a million) and print it out with leading zeros to get the TOTP code [17].

In other words, the starting seed for any account, or the secret as you can see it labelled in @mysk_co’s tweet above, is quite literally the key to producing every TOTP code you will ever need for that account.

Codes are for using, seeds are for securing

There are three reasons why you only ever type in those weirdly-computed six-digit codes when you you login, and never use (or even need to see) the seed again directly:

- You can’t work backwards from any of the codes to the key used to generate them. So intercepting TOTP codes, even in large numbers, doesn’t help you to reverse-engineer your way to any past or future logon codes.

- You can’t work forwards from the current code to the next one in sequence. Each code is computed independently, based on the seed, so intercepting a code today won’t help you logon in the future. The codes therefore act as one-time passwords.

- You never need to type the seed itself into a web page or password form. On a modern mobile phone, it can therefore be saved exactly once into the secure storage chip (sometimes called an enclave) on the device, where an attacker who steals your phone when it’s locked or turned off can’t extract it.

Simply put, a generated code is safe for one-time use, because the seed can’t be wrangled backwards from the code.

But the seed must be kept secret forever, because any code, from the start of 1970 until long after the likely heat death of the universe (263 seconds into the future, or about 0.3 trillion years), can be generated almost instantly from the seed.

Of course, the service you’re logging into needs a copy of your seed in order to verify that that you’ve supplied a code that matches the time at which you’re trying to log on.

So you need to trust the servers at the other end to take extra care to keep your seeds secure, even (or perhaps especially) if the service gets breached.

You also need to trust the application you’re using at your end never to reveal your seeds.

That means not displaying those seeds to anyone (a properly-coded app won’t even show the seed to you after you’ve entered it or scanned it in, because you simply don’t need to see it again), not releasing seeds to to any other apps, not writing them out to log files, adding them to backups or including them in debug output…

…and very, very definitely never transmitting any of your seeds over the network.

In fact, an app that uploads your seeds to a server anywhere in the world is either so incompetent that you should stop using it immediately, or so untrustworthy that you should treat it as cybercriminal malware.

What to do?

If you’ve grabbed an authenticator app recently, especially if you did it in a hurry as a result of Twitter’s recent announcement, review your choice in the light of what you now know.

If you were forced into paying a subscription for it; if the app is littered with ads; if the app comes with larger-than-life marketing and glowing reviews yet comes from a company you’ve never heard of; or if you’re simply having second thoughts, and something doesn’t feel right about it…

…consider switching to a mainstream app that your IT team has already approved, or that someone technical, whom you know and trust, can vouch for.

As mentioned above, Apple has a built-in 2FA code generator in Settings > Passwords, and Google has its own Google Authenticator app in the Play Store.

Your favourite security vendor probably has a free, no-ads, no-excitement code generator app that you can use, too. (Sophos has a standalone authenticator for iOS, and an authenticator component in the free Sophos Intercept X for Mobile app on both iOS and Android.)

If you do decide to switch authenticator app because you’re not sure about the one you’ve got, be sure to reset all the 2FA seeds for all the accounts you’ve entrusted to it.

QUANTIFYING THE RISK FOR YOURSELF

The risk of leaving your account protected by a 2FA seed that you think someone else might already know (or be able to figure out) is obvious.

You can prove this to yourself by using the TOTP algorithm we presented earlier, and feeding in [A] the “secret” string from Tommy Mysk’s tweet above and [B] the time he took the screenshot, which was 7:36pm Central European time on 2023-02-25, one hour ahead of UTC (Zulu time, denoted Z in the timestamp below).

The stolen seed is: 6QYW4P6KWALGCUWM Zulu time was: 2023-02-25T18:36:00Z Which is: 1,677,350,160 seconds into the Unix epoch

As you might expect, and as you can match up with the images in tweet above, the code produces the following output:

$ luax totp-mysk.lua Tommy Mysk's code was: 660680

As the famous videogame meme might put it: All his TOTP code are belong to us.

Scott Sminkey

This is excellent advice. Thank you. I am currently using 2FAS Authenticator on my Android phone. Now I’m concerned that it has an option to export “tokens” to a file and to Google Drive in a “hidden folder… only accessible to the 2FAS app” as a way to do a backup. Am I correct in guessing that by token, they mean seed?

By the way, I moved to 2FAS from the Sophos authenticator app for one reason only: I couldn’t reorder the list of sites/codes in the Sophos app. If 2FAS’s token = seed, I’ll go back to Sophos because I really don’t know who else to trust that doesn’t worry me about privacy. (Google and Microsoft are out because of that.)

Paul Ducklin

I assume “token” is another word for “seed”. (I usually use the word token to refer to a hardware device that stored or manages keys.)

As for the Sophos authenticator, the one built into the “Sophos Intercept X for Mobile app” puts the accounts in alphabetical order by name, IIRC. By adding (say) digits at the start of each on, e.g. “001 Zymurgy” and “999 Aardvark” you can therefore force them into a different order.

For the old-school “Sophos Authenticator” app (the one that’s orange rather than blue) I think you are right… they appear in the order they were added and that order can’t be changed.

Pete

Thanks Paul, for this nice article. Google Authenticator also offers the option to export the Codes to a new device (if Google Authenticator is installed). Might it be intentional to access them from other devices?

Paul Ducklin

I assume that the “export” isn’t a case of dumping them in a file for later. Assuming they are properly end-to-end encrypted in the transfer I can’t really see a problem. Maybe I will tone down that advice a little to avoid confusion… thanks for the comment.

David Pottage

In Google Authenticator, the “Transfer accounts” feature will generate one or more large and information dense QR codes that contains all the secrets for your many accounts encoded in the image. You are then expected to scan those QR codes using a copy of Google Authenticator on a second phone that you are transferring the data to.

Presumably the use case is for users who have upgraded to a new phone, and want to transfer data across before they wipe and dispose of their old phone. As I can tell there is no way to backup the secrets to a file that could be saved offline in any way, and attempting to take a screenshot of the QR code is blocked.

Paul Ducklin

Hmmm. Taking a picture of the QR code with another phone presumably works well enough…

As an aside: I’ve seen people take pics of the “seed” QR codes, where they presumably get swept up into cloud storage, backup files and perhaps even “emailed home for convenience”.

I strongly recommend you don’t do that!

LR

I am a newbie, learning about all of this. Also pretty basic user. Still using computer and phone as a tool rather than a generatior of money or career or for primary mode of communication. Dumped Twitter and FB ages ago.

Yes it was a terrible withrdrawl period, major social isolation…took a few years to regroup.

Since am not using Twitter et. al. need one be concerned about the 2 factor situation?

Paul Ducklin

I recommend you turn on 2FA for any account you can, just to make your password alone less useful if crooks figure it out. (And use a password manager if you can.)

If you decide to go with app-based 2FA, heed the advice above to find a trustworthy way to do it.

Twitter won’t let you use text messages for 2FA any more, but as you aren’t using Twitter your other apps or online services might.

However, Twitter is not the only service that demands a non-SMS-based approach to 2FA so if you adopt 2FA everywhere you are likely to need an app to generate one-time logon codes anyway.

Therefore, just to re-re-iterate, choose wisely when going for a 2FA app. If in doubt, speak to someone technical whom you know and trust…

HtH

Mark J. Kropf

I believe Sophos has good products, but some are not for me. I use AOSP (Graphene OS) and am not interested in tying into the Google Play Store or any solution which utilizes Google Play Services. I prefer to stay clear of Google rather than to expand its reach or its database, even if it has not had security issues, at least as of this point in time.

I have Aegis Authentication App and it appears to be respected, but I would consider using Sophos X interceptor if it had some access under F Droid or under Aurora App stores. Perhaps others with other AOSP or those who have phones with e-Foundation products, Volla Phones, etc. might well want to have the use of such a 2FAtype product servicing them.

Paul Ducklin

We used to have an APK download URL somewhere on our website… but I am not sure if we still do.

I’ve used our Intercept X for Mobile on a vanilla LineageOS with no Play Services (I installed the product on a Google Android device and then copied off the APK and sideloaded it onto Lineage), just for some screenshots.

But it’s not designed or intended to be used that way… and you have to rinse-and-repeat the APK “harvesting” when new versions come out, of course.

I don’t think I’ve ever tried our APK on GrapheneOS (which I did use for a short while on a personal device, but I could never got on with it – it felt like being on Disaster Area’s stunt ship, with all those black buttons with lamps that light up black to let you know you’ve pressed them).

Given that the our authenticator app on Android is just a part of the bigger Intercept X for Mobile (it’s an anti-virus, web filter and more), rather than just a minimalistic, focused-on-one-purpose 2FA app, I can’t imagine that many GrapheneOS users would care to install it just for the 2FA part.

I might give it a try later, just for interest’s sake, but we don’t officially test it on GrapheneOS, so if it does work that still won’t prove much.

TBH, most of our business customers don’t let their users install non-Google Android builds of any sort, or to get APKs from anywhere but the Play Store, so I’m guessing that “support AOSP-based Android flavours and put them through the same QA as Google Android for the sake of certainty…”

…well, let’s just say it’s probably not high on our Product Managers’ “Other things to try just because ” lists :-)

John Wills

Great article – thankyou!

I’m in the process of switching to 1Password for my password manager and wondering about using its built-in TOTP generator. I’ve been using the Microsoft authenticator for Microsoft accounts, the Google Authenticator for Google accounts, and Authy for everything else. I love Authy as it has (I hope) a cryptographically secure backup and sync process, and runs on and syncs between Macs, Windows, IOS, & Android – so I don’t need to hunt for an unnamed “device” when I’m told to enter the code during authentication to a site.

1Password also runs on and syncs between all these devices as well a WebApp and multiple browser extensions, however I’m concerned about using the same app to store the password and generate the TOTP code. I believe Sophos Home Premium also has a password manager and TOTP generator – I’m wondering if using the same app for both has come up in discussions?

I’m currently planning a multi-level MFA identity proofing process, whereby I’ll continue to use Authy for TOTP for the more sensitive sites, 1Password for others, and hardware keys for the most sensitive. Maybe my plan is overkill, but I can also use 1Password to help me track and manage the security level at which I authenticate to over 800 sites – a number which I plan to significantly reduce, in line with comments on this site after the LastPass breach ;).

Paul Ducklin

I can’t comment on Sophos Home (you’ll need to ask in the relevant support or community forums)…

…but my own preference is to have my 2FA codes somehow received by (e.g. SMS) or generated by my phone, or in/by a hardware token, at least for logins I do on my laptop.

I’ve generally avoided storing my 2FA seeds on my laptop… I commit them to my phone or to a Yubikey.

That’s my 3c.

I guess that using (say) 1Password for TOTP on sites where normally you might be happy with just a password at least adds a bit of extra protection against compromise due to a breach at the other ends.

Ironically, your password is never stored at the other end, while the seed is… but you can argue that your password is more likely to get breached because it’s supplied and lies around in memory for a while every time you login, prior to being hashed and verified. Thus it could where be scraped, sniffed and so on, right on the authentication server itself. (Your actual password does generally travel across the network.)

In other words, your password is at risk every time you present it to be hashed and then verified in the authentication back-end. But the seed is never presented or transmitted, only the one-time code, which can be sent off for verification deeper into the network, with no need for the authentication server itself ever to see or know the seed…

fred

Hi Duck.

Can’t help noticing in your reply to John Wills you had nothing to say about Authy.

Could I please ask specifically for your opinion / assessment as to the security and legitimacy of Authy by Twilio?

Paul Ducklin

I’ve never used it or looked at it, which is why I didn’t comment on it…

Spryte

Just managed to get MSAthenticator installed (working, I don’t know). Mostly as it was the easiest to use for importing a CSV (which hides in the old Sophos encryption app on my PC).

Did not realize you had a new one. May change things but I am old and not as quick as I used to be and I don’t those fancy bar codes so I do not allow camera access for any app.

Will attempt your Interceptor X thingy… Is it only Android? Linux?? I do have to get something for that machine.

Paul Ducklin

Sophos Intercept X for Mobile is, as the name suggests, for phones/tablets only (iOS, iPadOS, Android). We used to have a downloaed calls Sophos Anti-Virus for Linux, and it was free for work and home, but the free version was discontinued a year or three ago.

We replaced it with an broader-brush endpoint security product for Linux, but the new one can’t be used standalone – it needs a Sophos Central (cloud-based) login and relevant licensing before you can install and manage it.

Our home-use software for laptops and desktops went into Sophos Home, which is also cloud-based. IIRC it’s free for up to 3 users, or about £40 a year for 10 users (you can protect friends and family remotely, which makes the 10-user package popular) with support. But it’s Windows and Mac only – no Linux, sadly.

John Wills

I use and recommend the Sophos Home Premium solution for families. The cloud model took me a while to get used to after using McAfee, Malwarebytes, etc. but one or more family members can take the lead to support others using the web dashboard, including remote folks.

BTY, I misspoke in my previous post – Home Premium doesn’t have an anti-virus solution for IOS/Android. However, a subscription to home premium will get you support for the home version of Intercept X. I suspect this version is much scaled down in its capabilities from the commercial endpoint protection version (no Sophos Central integration) but I haven’t researched it yet. I believe it does also have both a password manager and TOTP code generator though, so I’ll follow up with my previous question to support as Paul suggested (some day real soon now ;).

Paul Ducklin

Just to be clear, the “Sophos Intercept X for Mobile” app is free for anyone to use as a standalone product, whether they have a Sophos Home licence or not…

…so if you install our mobile app from the App Store or Google Play you get the 2FA generator and the mini-password manager (compatible with KeePass vault files, not sure which versions offhand).

David Hart

Hi Paul,

I use Sophos Intercept-X app on Android for generating 2FA One Time Password codes and find it works well.

Important to mention too I think, to back up the Intercept-X app settings, which include your 2FA settings and store a copy remotely from the device so that if you should lose your device you can later re-install it on the replacement device and regain access again to the accounts you set up 2FA on.

Regards.

David

Eazymandias

I am interested in Sophos Intercept X for security and 2FA but I have a question. My phone has a built-in security suite that can’t be uninstalled (a Xiaomi Rednote), if I install Intercept X, isn’t there a risk of conflict between the 2 apps?

Paul Ducklin

I can’t answer that, but in the case of mobile apps, the issue of “conflict” often seems to boil down to features that only one app is allowed to provide at a time (e.g. IIRC you can’t chain together Messaging apps; you have to settle on one). Thus you don’t so much have “conflicts” as features where your app choice is limited.

Why not just try it and see? The 2FA part doesn’t interact with other parts of the system to modify their behaviour (as, say, a virus scanner might) so it ought to work independently and correctly even if you other authenticator installed.

If there are security-related parts that we offer but can’t activate because the system itself has decided to shut us out, our app ought to tell you if you try to turn them on (though the rest of it should work just fine).

You might find some fellow Rednote users in the community.sophos.com pages whom you could ask.

(I only use Android for research, not for daily commuting, so I tend to stick to Pixels and emulated devices. Sorry I can’t be more precise than above.)

HtH.

Eazymandias

Thx for the clarification. I’ll give it a try.

Mick Marshall

One of my users has installed a Microsoft Authenticator App lookalike and used the app to scan the Microsoft/Azure QR code as part of the 2FA setup process. Is their account at risk now the rogue app has scanned the QR code?

Paul Ducklin

It’s impossible to say for sure without analysing the actual app… but if the user intended to install the Microsoft app but didn’t, my advice would be to get rid of the lookalike, replace it with the app they were actually after, and re-enrol with a new 2FA sequence in the new app. I assume that will mean cancelling 2FA via the first app, removing it, and then essentially starting over with the genuine app.