Last week, we wrote about a bunch of memory management bugs that were fixed in the latest security update of the popular OpenSSL encryption library.

Along with those memory bugs, we also reported on a bug dubbed CVE-2022-4304: Timing Oracle in RSA Decryption.

In this bug, firing the same encrypted message over and over again at a server, but modifying the padding at the end of the data to make the data invalid, and thus provoking some sort of unpredictable behaviour…

…wouldn’t take a consistent amount of time, assuming you were close to the target on the network that you could reliably guess how long the data transfer part of the process would take.

Not all data processed equally

If you fire off a request, time how long the answer takes, and subtract the time consumed in the low-level sending-and-receiving of the network data, you know how long the server took to do its internal computation to process the request.

Even if you aren’t sure how much time is used up in the network, you can look for variations in round-trip times by firing off lots of requests and collecting loads of samples.

If the network is reliable enough to assume that the networking overhead is largely constant, you may be able to use statistical methods to infer which sort of data modification causes what sort of extra processing delay.

From this, you many be able to infer something about the the structure, or even the content, of the original unencrypted data that’s supposed to be kept secret inside each repeated request.

Even if you can only extract one byte of plaintext, well, that’s not supposed to happen.

So-called timing attacks of this sort are always troublesome, even if you might need to send millions of bogus packets and time them all to have any chance of recovering just one byte of plaintext data…

…because networks are faster, more predictable, and capable of handling much more load than they were just a few years ago.

You might think that millions of treacherous packets spammed at you in, say, the next hour would stand out like a sort thumb.

But “a million packets an hour more or less than usual” simply isn’t a particularly large variation any more.

Similar “oracle” bug in GnuTLS

Well, the same person who reported the fixed-at-last bug timing bug in OpenSSL also reported a similar bug in GnuTLS at about the same time.

This one has the bug identifier CVE-2023-0361.

Although GnuTLS isn’t quite as popular or widely-used as OpenSSL, you probably have a number of programs in your IT estate, or even on your own computer, that use it or include it, possibly including FFmpeg, GnuPG, Mplayer, QEMU, Rdesktop, Samba, Wget and Wireshark.

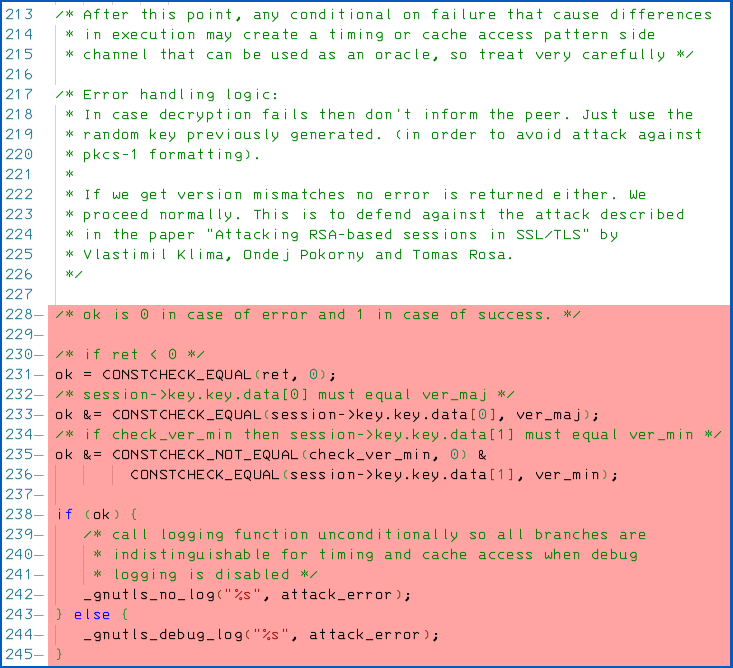

Ironically, the timing flaw in GnuTLS appeared in code that was supposed to log timing attack errors in the first place.

As you can see from the code difference (diff) below, the programmer was aware that any conditional (if ... then) operation used in checking and dealing with a decryption error might produce timing variations, because CPUs generally take a different amount of time depending on which way your code goes after a “branch” instruction.

(That’s especially true for a branch that often goes one way and seldom the other, because CPUs tend to remember, or cache, code that runs repeatedly in order to improve performance, thus making the infrequently-taken code run detectably slower.)

But the programmer still wanted to log that an attack might be happening, which happens if the if (ok) test above fails and branches into the else { ... } section.

At this point, the code calls the _gnutls_debug_log() function, which could take quite a while to do its work.

Therefore the coder inserted a deliberate call to _gnutls_no_log() in the then { ... } part of the code, which pretends to log an “attack” when there isn’t one, in order to try to even up the time that the code spends in either direction that the if (ok) branch instruction can take.

Apparently, however, the two code paths were not sufficiently similar in the time they used up (or perhaps the _gnutls_debug_log() function on its own was insufficiently consistent in dealing with different sorts of error), and an attacker could begin to distinguish decryption telltales after a million or so tries.

What to do?

If you’re a programmer: the bug fix here was simple, and followed the “less is more” principle.

The code in pink above, which was deemed not to give terribly useful attack detection data anyway, was simply deleted, on the grounds that code that’s not there can’t be compiled in by mistake, regardless of your build settings…

…and code that’s not compiled in can never run, whether by accident or design.

If you’re a GnuTLS user: the recently-released version 3.7.9 and the “new product flavour” 3.8.0 have this fix, along with various others, included.

If you’re running a Linux distro, check for updates to any centrally-managed shared library version of GnuTLS you have, as well as for apps that bring their own version along.

On Linux, search for files with the name libgnutls*.so to find any shared libraries lying around, and search for gnutls-cli to find any copies of the command line utility that’s often included with the library.

You can run gnutls-cli -vv to find out which version of libgnutls it’s dynamically linked to:

$ gnutls-cli -vv gnutls-cli 3.7.9 <-- my Linux distro got the update last Friday (2023-02-10)

Paul Dodd

This part is completely redundant

“on the grounds that code that’s not there can’t be compiled in by mistake, regardless of your build settings…

…and code that’s not compiled in can never run, whether by accident or design.”

Paul Ducklin

Not exactly. Lots of software has code that comes out differently based on compile time settings, and that behaves differently depending on runtime settings, which confounds and complicates security testing.

If you look at the GnuTLS bugfix link I included, you will see a discussion that first suggests putting the suspicious code behind an #ifdef that makes it hard to compile it into production builds by mistake (i.e. the code is always present in the source but probably not in the version you ship), followed by a stronger suggestion that leaving the code out completely is the best way to secure it, so it’s not merely unlikely to end up turned on in production builds, or unlikely to compiled in by mistake, but *guaranteed to be absent and therefore uncallable in all circumstances*.

If you can find a clearer way to say that in two half-sentences I am happy to change it…