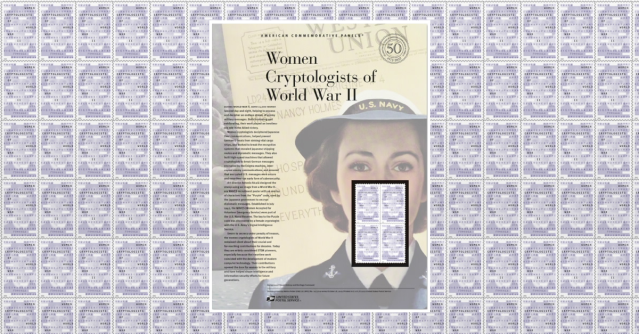

The US Postal Service just issued a commemorative stamp to remember the service of some 11,000 women cryptologists during World War 2.

Like their Bletchley Park counterparts in the UK, these wartime heros didn’t finish the war with any sort of hero’s welcome back into civilian life.

Indeed, they got no public recognition at all for the amazing physical and intellectual effort they put into decrypting and decoding enemy intelligence.

Make no mistake, this work helped enormously towards the ultimate Allied victory over both the Nazis in Europe and the Imperial Japanese in the Pacific.

As the US Post Office puts it:

Sworn to secrecy under penalty of treason, the women cryptologists of World War II remained silent about their crucial and far-reaching contributions for decades. Today, they are widely considered STEM pioneers, especially because their wartime work coincided with the development of modern computer technology. Their contributions opened the door for women in the military and have helped shape intelligence and information security efforts for future generations.

What did you do in the war, Mom?

You can just imagine the sort of conversations that many of these women must have had with their friends and families once peace broke out at the end of 1945:

Q. What did you do in the war, Mom?

A. Oh, y’know, a bit of this and that.

Q. Like what, Mom?

A. Oh, clerical work, mainly. Just a desk job.

Q. But what did you actually *do*, Mom?

A. Oh, adding, subtracting, writing notes, that sort of thing.

Q. Must have been pretty boring!

In fact, the pressure of being a cryptographer during World War 2 was enormous, given that stealing a march on the enemy figuratively, by decrypting their plans up front, was vital to stealing a march on them literally.

Battles could be won, or better yet avoided; bombing raids could be diverted or disrupted; unarmed merchant ships carrying vital supplies could be spared from decimation by submarines; and much, much more.

A desk job in name only

And although, strictly speaking, cryptology was a desk job, it wasn’t your usual 9-to-5 sort of work.

In the early 1940s, Mavis Batey, a woman cryptologist at Bletchley Park in England famously made a cryptographic breakthough in unscrambling a mysterious Engima cipher-machine message from Italy that said, simply, TODAY'S THE DAY MINUS THREE.

Clearly, they were on to something big… but they still had to figure out what it was, and that left just three days to do it in:

[W]e worked for three days. It was all the nail-biting stuff of keeping up all night working. One kept thinking: ‘Well, would one be better at it if one had a little sleep or shall we just go on?’ — and it did take nearly all of three days. Then a very, very large message came in.

Batey’s US counterparts primarily faced a different set of challenges to the UK cryptologists, notably including the Japanese cipher machine known as PURPLE.

The PURPLE device was a home-grown device based on telephone switches, not the proprietary wired disks of the Nazi’s prized Enigma, which was a commercial product.

But shortcuts in PURPLE’s design (it encrypted 20 letters of the Roman alphabet in one way, and the remaining 6 in another, making it more predictable), plus the perspicacity of cryptologists such as Genevieve Grotjan, who served with the US Army Signal Intelligence Service, led to spectacular successes in reading Japanese secrets.

In the words of the Postal Service:

They deciphered Japanese fleet communications, helped prevent German U-boats from sinking vital cargo ships, and worked to break the encryption systems that revealed Japanese shipping routes and diplomatic messages.

“The other side isn’t smart enough”

Fortunately for the Allied forces in the Pacific theatre of war, the Japanese seem to have fallen into the same trap of self-belief that the Nazis did with their encryption devices.

The Japanese military commanders couldn’t bring themselves to accept, or apparently even to assume as a precaution, that the enemy might be smart enough to crack the cipher, and carried on using it right to the end.

So, as the French might say, “To the Women Cryptologists of World War 2: Chapeau!”

You can buy commemorative sheets and first-day covers directly from the USPS…

…and you might also like to have a crack (see what we did there?) at a little decryption puzzle that’s posed on what’s called the selvedge, or selvage, of the stamp sheets. (The selvedge is, quite literally, the part around of the edge of the stamp sheet that holds the unused stamps together.)

Here it is (the same cipher is used for all four parts):

ZRPH QF UB SWRORJLVWV RIZRUOGZDULL / FLSKHU / DQDOBCH / VHFUHW

Let us know in the comments if you solve it (we’ll redact correct answers until everyone has had time to have a go).

For hints on how to solve it, have a read of our popular article on cryptographic history: