Here’s an interesting paper from the recent 2022 USENIX conference: Mining Node.js Vulnerabilities via Object Dependence Graph and Query.

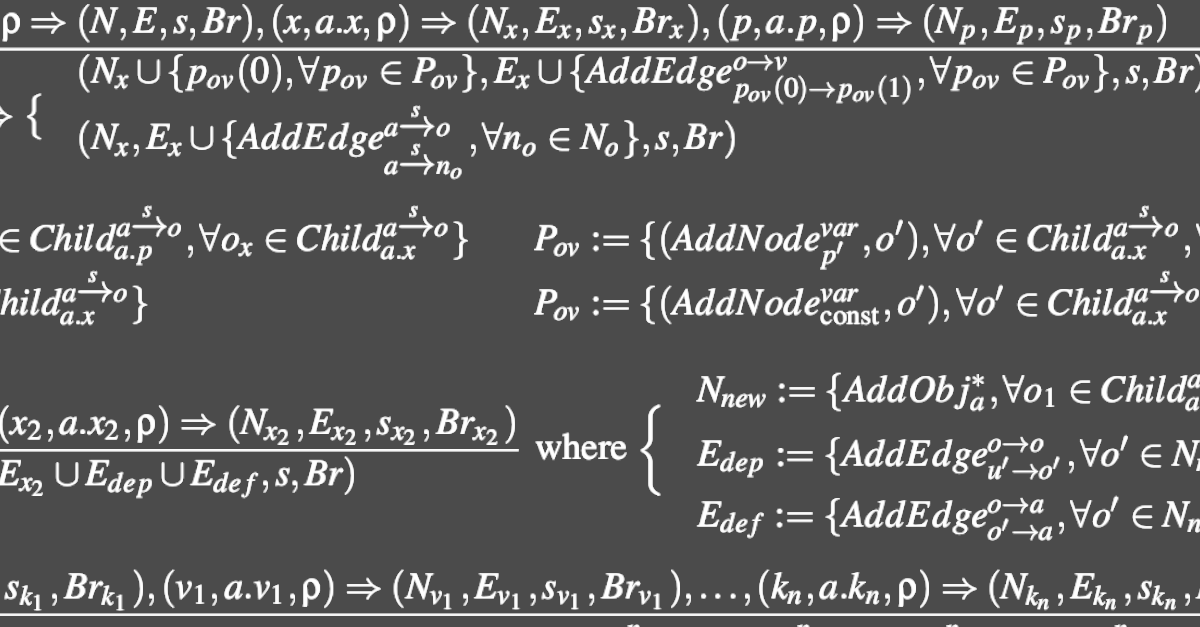

We’re going to cheat a little bit here by not digging into and explaining the core research presented by the authors of the paper (some mathematics, and knowledge of operational semantics notation is desirable when reading it), which is a method for the static analysis of source code that they call ODGEN, short for Object Dependence Graph Generator.

Instead, we want to focus on the implications of what they were able to discover in the Node Package Manager (NPM) JavaScript ecosystem, largely automatically, by using their ODGEN tools in real life.

One important fact here is, as we mentioned above, that their tools are intended for what’s known as static analysis.

That’s where you aim to review source code for likely (or actual) coding blunders and security holes without actually running it at all.

Testing-it-by-running-it is a much more time-consuming process that generally takes longer to set up, and longer to do.

As you can imagine, however, so-called dynamic analysis – actually building the software so you can run it and expose it to real data in controlled ways – generally gives much more thorough results, and is much more likely to expose arcane and dangerous bugs than simply “looking at it carefully and intuiting how it works”.

But dynamic analysis is not only time consuming, but also difficult to do well.

By this, we really mean to say that dynamic software testing is very easy to do badly, even if you spend ages on the task, because it’s easy to end up with an impressive number of tests that are nevertheless not quite as varied as you thought, and that your software is almost certain to pass, no matter what. Dynamic software testing sometimes ends up like a teacher who sets the same exam questions year after year, so that students who have concentrated entirely on practising “past papers” end up doing as well as students who have genuinely mastered the subject.

A straggly web of supply chain dependencies

In today’s huge software source code ecosystems, of which global open source repositories such as NPM, PyPI, PHP Packagist and RubyGems are well-known examples, many software products rely on extensive collections of other people’s packages, forming a complex, straggly web of supply chain dependencies.

Implicit in those dependencies, as you can imagine, is a dependency on each dynamic test suite provided by each underlying package – and those individual tests generally don’t (indeed, can’t) take into account how all the packages will interact when they’re combined to form your own, unique application.

So, although static analysis on its own isn’t really adequate, it’s still an excellent starting point for scanning software repositories for glaring holes, not least because static analysis can be done “offline”.

In particular, you can regularly and routinely scan all the source code packages you use, without needing to construct them into running programs, and without needing to come up with believable test scripts that force those programs to run in a realistic variety of ways.

You can even scan entire software repositories, including packages you might never need to use, in order to shake out code (or to identify authors) whose software you’re disinclined to trust before even trying it.

Better yet, some types of static analysis can be used to look through all your software for bugs caused by similar programming blunders that you just found via dynamic analysis (or that were reported through a bug bounty system) in one single part of one single software product.

For example, imagine a real-world bug report that came in from the wild based on one specific place in your code where you had used a coding style that caused a use-after-free memory error.

A use-after-free is where you are certain that you are finished with a certain block of memory, and hand it back so it can be used elsewhere, but then forget it’s not yours any more and keep using it anyway. Like accidentally driving home from work to your old address months after you moved out, just out of habit, and wondering why there’s a weird car in the driveway.

If someone has copied-and-pasted that buggy code into other software components in your company repository, you might be able to find them with a text search, assuming that the overall structure of the code was retained, and that comments and variable names weren’t changed too much.

But if other programmers merely followed the same coding idiom, perhaps even rewriting the flawed code in a different programming language (in the jargon, so that it was lexically different)…

…then text search would be close to useless.

Wouldn’t it be handy?

Wouldn’t it be handy if you could statically search your entire codebase for existing programming blunders, based not on text strings but instead on functional features such as code flow and data dependencies?

Well, in the USENIX paper we’re discussing here, the authors have attempted to build a static analysis tool that combines a number of different code characteristics into a compact representation denoting “how the code turns its inputs into its outputs, and which other parts of the code get to influence the results”.

The process is based on the aforementioned object dependency graphs.

Hugely simplified, the idea is to label source code statically so that you can tell which combinations of code-and-data (objects) in use at one point can affect objects that are used later on.

Then, it should be possible to search for known-bad code behaviours – smells, in the jargon – without actually needing to test the software in a live run, and without needing to rely only on text matching in the source.

In other words, you may be able to detect if coder A has produced a similar bug to the one you just found from coder B, regardless of whether A literally copied B’s code, followed B’s flawed advice, or simply picked the same bad workplace habits as B.

Loosely speaking, good static analysis of code, despite the fact that it never watches the software running in real life, can help to identify poor programming right at the start, before you inject your own project with bugs that might be subtle (or rare) enough in real life that they never show up, even under extensive and rigorous live testing.

And that’s the story we set out to tell you at the start.

300,000 packages processed

The authors of the paper applied their ODGEN system to 300,000 JavaScript packages from the NPM repository to filter those that their system suggested might contain vulnerabilities.

Of those, they kept packages with more than 1000 weekly downloads (it seems they didn’t have time to process all the results), and determined by further examination those packages in which they thought they’d uncovered an exploitable bug.

In those, they discovered 180 harmful security bugs, including 80 command injection vulnerabilities (that’s where untrusted data can be passed into system commands to achieve unwanted results, typically including remote code execution), and 14 further code execution bugs.

Of these, 27 were ultimately given CVE numbers, recognising them as “official” security holes.

Unfortunately, all those CVEs are dated 2019 and 2020, because the practical part of the work in this paper was done more than two years ago, but it’s only been written up now.

Nevertheless, even if you work in less rarified air than academics seem to (for most active cybersecurity responders, fighting today’s cybercriminals means finishing any research you’ve done as soon as you can so you can use it right away)…

…if you’re looking for research topics to help against supply chain attacks in today’s giant-scale software repositories, don’t overlook static code analysis.

Life in the old dog yet

Static analysis has fallen into some disfavour in recent years, not least because popular dynamic languages like JavaScript make static processing frustratingly hard.

For example, a JavaScript variable might be an integer at one moment, then have a text string “added” to it perfectly legally albeit incorrectly, thus turning it into a text string, and might later end up as yet another object type altogether.

And a dynamically generated text string can magically turn into a new JavaScript program, compiled and executed at runtime, thus introducing behaviour (and bugs) that didn’t even exist when the static analysis was done.

But this paper suggests that, even for dynamic languages, regular static analysis of the repositories you rely upon can still help you enormously.

Static tools can not only find latent bugs in code you’re already using, even in JavaScript, but also help you to judge the underlying quality of the code in any packages you’re thinking of adopting.

LEARN MORE ABOUT PREVENTING SUPPLY-CHAIN ATTACKS

This podcast features Sophos expert Chester Wisniewski, Principal Research Scientist at Sophos, and it’s full of useful and actionable advice on dealing with supply chain attacks, based on the lessons we can learn from giant attacks in the past, such as Kaseya and SolarWinds.

If no audio player appears above, listen directly on Soundcloud.

You can also read the entire podcast as a full transcript.

David

I wasn’t aware that JavaScript was vulnerable to use-after-free bugs. I had always thought was something for C and C++, and also Delphi, going further back. Not sure how one would code up a use-after-free scenario in JavaScript?