This month’s scheduled Firefox release is out, with the new 102.0 version patching 19 CVE-numbered bugs.

Despite the large number of CVEs, the patches don’t include any bugs already being exploited in the wild (known in the jargon as zero-days), and don’t include any bugs labelled Critical.

Perhaps the most significant patch is the one for CVE-2022-34479, entitled: A popup window could be resized in a way to overlay the address bar with web content.

This bug allows a malicious website to create a popup window and then resize it to overwrite the browser’s own address bar.

Fortunately, this address bar spoofing bug only applies to Firefox on Linux; on other operating systems, the bug apparently can’t be triggered.

As you know, the browser’s own visual components, including the menu bar, search bar, address bar, security alerts, HTTPS padlock icon and more, are supposed to be shielded from manipulation by untrusted web pages rendered by the browser.

These sacrosanct user interface components are known in the jargon as chrome (from which Google’s browser gets its name, in case you were wondering).

Browser chrome is off-limits to web pages for obvious reasons – to prevent bogus websites from misrepresenting themselves as trustworthy.

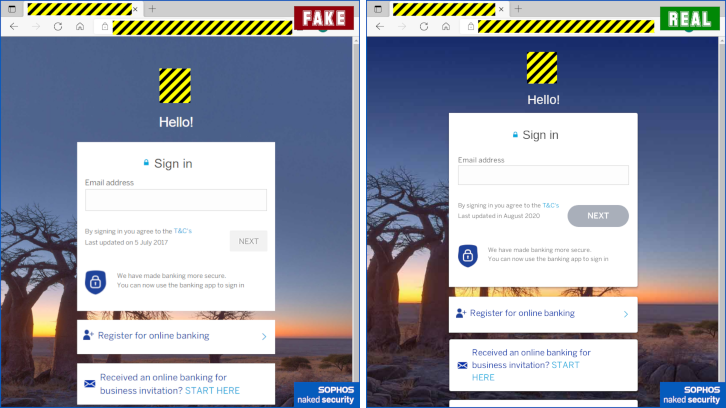

This means that even though phishing sites often reproduce the look-and-feel of a legitimate website with uncanny precision, they aren’t supposed to be able to trick your browser into presenting them as if they were downloaded from a genuine URL.

Side-by-side view of a recent scam targeting a South African bank

Image-based RCEs

Intriguingly, this month’s fixes includes two CVES that have the same bug title, and that permit the same security misbehaviour, even though they’re otherwise unrelated and were found by different bug-hunters.

CVE-2022-34482 and CVE-2022-34483 are both headlined: Drag and drop of malicious image could have led to malicious executable and potential code execution.

As the bug name suggests, these flaws mean that an image file that you save to your desktop by dragging-and dropping it from Firefox could end up saved to disk with an extension such as .EXE instead of with the more innocent extension you were expecting, such as .PNG or .JPG.

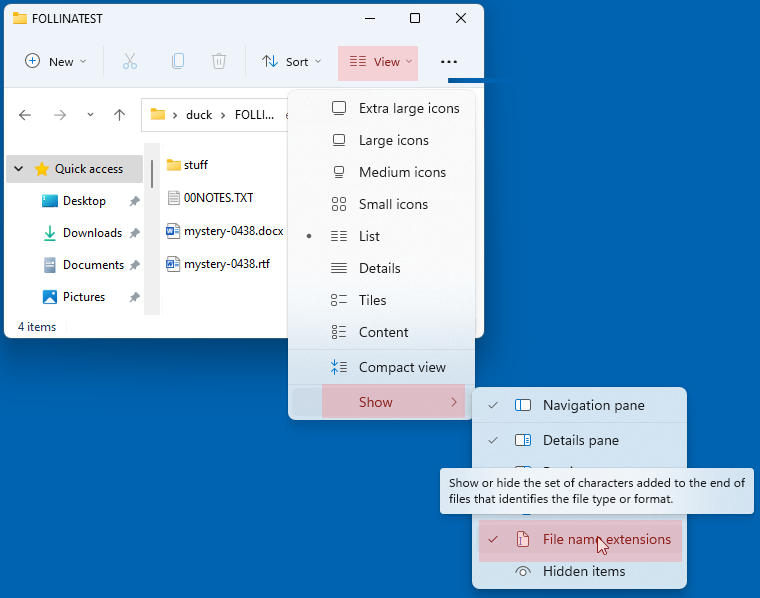

Given that Windows annoyingly (and wrongly, in our opinion), doesn’t show you file extensions by default, these Firefox bugs could lead to you to trust the file you just dropped onto your desktop, and therefore to open it without ever being aware of its true filename.

(If you save the file by more traditional means such as Right click > Save Image As…, the full filename, complete with extension, is revealed.)

These bugs aren’t true remote code execution (RCE) vulnerabilities, given that an attacker needs to persuade you to save content from a web page onto your computer and then to open it up from there, but they do make it much more likely that you would launch a malicious file by mistake.

As an aside, we strongly recommend that you tell Windows to show all file extensions, instead of secretly suppressing them, by changing the File name extensions option in File Explorer.

Fixes for Follina!

Last month’s Big Bad Windows Bug was Follina, properly known as CVE-2022-30190.

Follina was a nasty code execution exploit whereby an attacker could send you a booby-trapped Microsoft Office document that linked to a URL starting with the characters ms-msdt:.

That document would then automatically run PowerShell code of the attacker’s choice, even if all you did was browse to the file in Explorer with the preview pane turned on.

Firefox has weighed in with additional mitigations of its own by essentially “disowning” Microsoft’s proprietary URL schemes starting with ms-msdt: and other potentially risky names, so they no longer even ask you if you want to process the URL:

The

ms-msdt,search, andsearch-msprotocols deliver content to Microsoft applications, bypassing the browser, when a user accepts a prompt. These applications have had known vulnerabilities, exploited in the wild (although we know of none exploited through Firefox), so in this release Firefox has blocked these protocols from prompting the user to open them.

What to do?

Just visit Help > About Firefox to check what version you’re on – you’re looking for 102.0.

If you’re up-to-date then a popup will tell you so; if not, the popup will offer to start the update for you.

If you or your company has stuck to the Firefox Extended Support Release (ESR), which includes feature updates only every few months but delivers security updates whenever needed, you’re looking for ESR 91.11.

Remember that ESR 91.11 denotes Firefox 91 with 11 updates’ worth of security fixes, and because 91+11 = 102, you can easily tell that you’re level with the latest mainstream version as far as security patches are concerned.

Linux and BSD users who have installed Firefox via their distro will need to check with their distro for the needed update.

Fred

You probably made a type: CVE-2022-34482 and CVE-2022-34482 , where the latter one should be ….83

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks!

Ian Young

Hi Paul,

Thank you for the insightful article. I did spot a typo, you list the two CVEs CVE-2022-34482 and CVE-2022-34482, I believe the second should read CVE-2022-34483. The link looks correct.

I find your articles interesting and often forward them on to colleagues, to keep cyber security at the forefront of the minds.

Cheers

Ian

Paul Ducklin

I know what happened – during preparations, I mixed up the CVE numbers in the text and in the links, so both CVEs were linking to the same URL… so I seem to have “over-corrected” to end up with the right URLs and the wrong numbers in the text. Fortunately, the links land at adjacent paragraphs in the security advisory. As mentioned above, I have fixed it now.

Thanks for the comment and your kind words.

Kyle

Yay now I can’t even trust the URL in my nav bar anymore.

Happy 2022, everyone!

Paul Ducklin

To be clear, that bug [a] wasn’t exploited in the wild (so far as we know) and [b] is fixed now.

Kyle

Don’t get me wrong – I’m really glad it was caught early. But my mind immediately goes to the 2018 event-stream NPM malware that was found a week after release – because the malware was spitting out deprecation warnings on bleeding edge versions of Node.js. It was literally discovered by accident. It was not noticed because of peer review or careful auditing. And this was a highly popular package that had something like 300k downloads per week at the time (IIRC). That’s the part that scares me.

When a bug like this Firefox one is even possible, my mind immediately goes to “How long before something like this goes uncaught? Will we ever have an unnoticed regression? Can you even discover future regressions with automated testing, or testing for this not feasible?”

Paul Ducklin

I’m not sure it’s fair to compare Mozilla’s development and bug-hunting process to the Wild West of scripting language package repositories and their amazing webs of deep and often unappreciated dependencies (try searching for “NPM left-pad crisis” as an indicator or how ill-documented some development projects can get).

As for “how long before another bug of this sort goes uncaught”… I can’t answer that, but the fact that this one was caught at least indicates that such coding mistakes aren’t inevitably *uncaught*.

In theory, test suites should (and often do) seek out regressions that reintroduce previously-known bugs, because you generally know what you fixed and how the bug was triggered last time. But you can’t automatically find all regressions, just as you can’t automatically find all possible items of malware. The Halting Problem suggests why this just isn’t possible…

(If I wanted to fret about regressions – a fancy name for “accidentally reintroducing an old bug”) then I’d probably focus my fear on things like race conditions. (Maybe increased use of Rust in Mozilla’s code will help here? Rust fans often suggest that bugs are less likely in Rust, but no one thinks it’s a panacea.)

…