A pair of incidents at different organizations in which attackers deployed a ransomware called Entropy were preceded by infections with tools that provided the attackers with remote access — Cobalt Strike beacons and Dridex malware — on some of the targets’ computers, before the attackers launched the ransomware.

Sophos analysts hadn’t encountered Entropy prior to these incidents. Notably, there were significant differences in the methodologies employed by the attackers between both cases: How the attackers gained a foothold in the targets; the time the attackers spent inside the target’s network; and the malware that was used to prepare the final phase of the attack were substantially different.

Some aspects of the attacks were consistent: In both cases, the attackers relied heavily on Cobalt Strike as a means to infect more machines, meeting variable levels of success depending on whether the target had protection installed on a given machine. The attackers also performed redundant exfiltration of private data to more than one cloud storage provider. During a forensic analysis, we encountered multiple instances of Dridex, the well-known, general-purpose malware that its operators can use to distribute other malware.

In the first incident, the attackers exploited the ProxyShell vulnerability on the network belonging to a North American media organization, to install a remote shell on the target’s Exchange server, and leveraged that to spread Cobalt Strike beacons to other computers. Over a four-month period, the attackers took their time probing the organization, and stealing data, before launching the attack at the beginning of December. Subsequent post-attack forensics revealed several Dridex payloads on some of the infected machines.

Analysis of the second Entropy attack — this time on a regional government organization — revealed that a malicious email attachment had infected a user’s computer with the Dridex botnet Trojan, and that the attackers used Dridex to deliver additional malware (as well as the commercial remote access utility ScreenConnect) and move laterally within the target’s network. Significantly, in this second attack, only about 75 hours passed between the initial detection of a suspicious login attempt on a single machine and the attackers commencing data exfiltration from the target – installing, then using WinRAR to compress files into archives, then uploading the archives to a variety of cloud storage providers, including privatlab.com, dropmefiles.com, and mega.nz.

And while not all machines on either organization’s networks had endpoint protection installed prior to the attack, on the ones where protection existed, the attackers unsuccessfully attempting to execute the ransomware turned up an intriguingly coincidental detection signature: The packer code used to protect the Entropy ransomware was picked up by a detection signature (Mal/EncPk-APX) that analysts had previously created to detect the packer code employed by Dridex.

Under additional reverse-engineering scrutiny, SophosLabs analysts discovered that some of the other subroutines the ransomware uses to obfuscate its behavior (and make it harder for analysts to study it) were reminiscent of subroutines used for similar functions in Dridex – though not conclusively, and not without a lot of effort to strip away other obfuscations that complicated the code-comparison process.

Attacker behavior and use of free and commercial tools

The ransomware attackers in both cases used freely-available tools like the Windows Sysinternals tools PsExec and PsKill, and the utility AdFind, which is designed to let IT admins query Active Directory servers. They also used the free compression utility WinRAR to package up collections of private data they stole, and then uploaded it to a variety of cloud storage providers using the Chrome browser.

These tactics are, unfortunately, quite common among ransomware threat actors. Endpoint protection tools don’t typically block the use of these and other utility programs since they do have legitimate uses.

The attackers, in both cases, tried repeatedly (and unsuccessfully) to load and launch Cobalt Strike remote control tools on machines during the final phase of the attack. In the second attack, after multiple failed attempts to use Cobalt Strike, they also tried to install Metasploit’s Meterpreter on some machines, and eventually decided to install a commercial remote access tool called ScreenConnect. The attackers attempted to use file-sharing tools within ScreenConnect to push Cobalt Strike down to the protected machines, but ultimately failed.

Eventually, the attackers dropped a set of files onto an Active Directory server they had taken control of. The threat actor dropped these files in C:\share$:

- comps.txt – List of hosts to attack.

- pdf.dll – The ransomware payload

- PsExec.exe – a legitimate application by Microsoft

- COPY.bat – Instructions to copy pdf.dll to all the hosts using PsExec

- EXE.bat – Instructions to execute pdf.dll to all the hosts using PsExec

They then ran the COPY batch script followed by the EXE batch script.

Comparing subroutines in Dridex and Entropy

The Entropy samples in both cases were delivered in the form of Windows DLL files compiled for a 32-bit architecture. Dridex payloads were recovered from various systems in both an EXE and DLL format, compiled for 32-bit and 64-bit architectures. We looked at the 32-bit Dridex bots for our comparison.

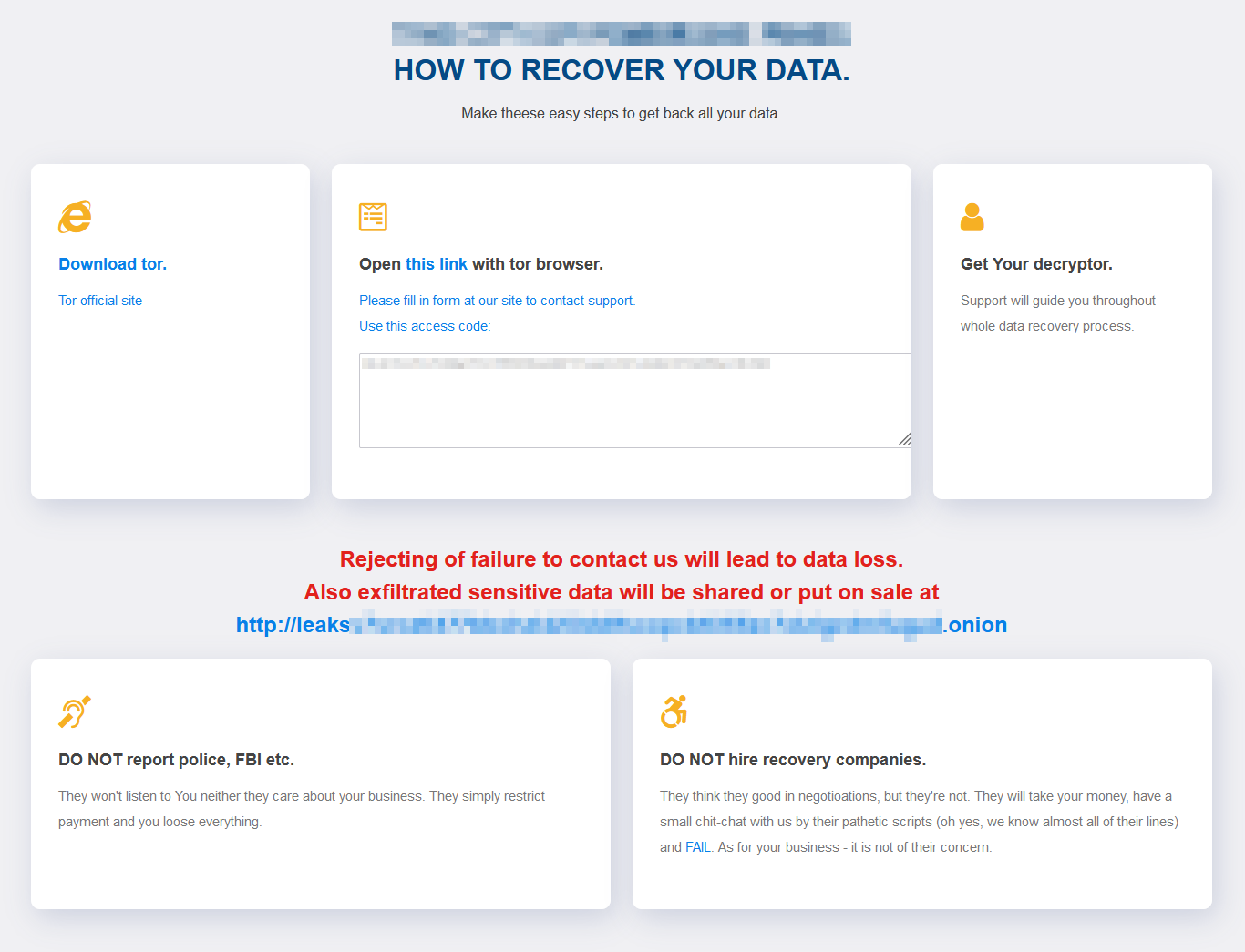

The threat actors had compiled custom versions of the Entropy ransomware DLL for each targeted organization. The malware contains hardcoded references to the targeted organization in its code, including text and images later used in an HTML ransom note dropped on infected machines.

The ransom note cautions victims not to contact police or the FBI (“They won’t listen to You neither they care about your business”) or to hire ransom negotiators or data recovery firms (“They think they good in negotioations, but they’re not. They will take your money, have a small chit-chat with us by their pathetic scripts (oh yes, we know almost all of their lines) and FAIL.”) with the word FAIL linking to a 2019 investigation by ProPublica that reported how some companies who claim to specialize in ransomware data recovery just pay the ransom.

Attackers executed it using a command line that passed two parameters to the DLL; The first is a standard function call, DllRegisterServer, but the second parameter was a random-looking string of characters that serve as a sort of password: The ransomware wouldn’t run properly without it.

Fortunately, we were able to find the precise command the attackers used to launch the malware, so we could study the samples in a controlled environment. Entropy’s execution command looked like this:

regsvr32 c:\users\public\xyz.dll DllRegisterServer <20 random characters>

Ransomware necessarily would have significant functional differences from a more general-purpose botnet bot like Dridex, which complicates a line-by-line comparison. Instead, we studied aspects of the code both malware apparently use in an attempt to complicate analysis: The packer code, which prevents easy static analysis of the underlying malware; a subroutine that the programs use to conceal the API calls they make; and a subroutine that decrypts encrypted text strings embedded within the malware.

Entropy’s Packer behavior

The packer Entropy uses works in two stages to decompress the program code: In the first layer, it allocates some memory, then copies the encrypted data to that memory space and the packer transfers execution to the first layer. Next, the packer decrypts the code into another portion of the same memory allocation where it stored the encrypted data, and then transfers the execution to this second layer.

The instructions that dictate how Entropy performs the first “layer” of unpacking are similar enough to Dridex that the analyst who looked at the packer code, and in particular the portion that refers to an API called LdrLoadDll — and that subroutine’s behavior, described it as “very much like a Dridex v4 loader,” and compared it to a similar loader used by a Dridex sample from 2018. The behavior in question has been highlighted in other vendors’ research about Dridex. Specifically, it is looking for a DLL named snxhk.dll, which is a memory protection component of another company’s endpoint security product, in order to sabotage that protection.

Notably, Sophos has had a static detection for the Dridex packer in our endpoint products for some time. The signature name is Mal/EncPk-APX, which is notable because telemetry shows that during these incidents, machines protected by Sophos made a detection of that packer when Entropy, but not Dridex, was present.

Another SophosLabs manager also had notes about detections of this particular packer code on Sophos-protected machines where attackers had unsuccessfully attempted to run the ransomware called DoppelPaymer. That ransomware, whose origin (like Dridex) has been attributed to the gang known as Evil Corp, was in use from about April, 2019 until May, 2021. After the US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) sanctioned Evil Corp over Dridex in December, 2019, the group went through a rapid set of name and branding changes to their ransomware, cycling through many names including WastedLocker, Hades, Phoenix, Grief, Macaw, and now, possibly, Entropy.

Vectored Exception Handler subroutine

Once the malware has unpacked itself, the packer’s final act is to start up the malware at a memory location known as the entrypoint, which is where the first instructions the malware executes begin. In both the case of Dridex and Entropy, the entrypoint code sets up a process called a Vectored Exception Handler (VEH), which is another form of anti-analysis wrinkle that malware authors may insert into the final product. A VEH sets up an alternate way for the program to invoke API calls in the operating system, which makes it harder for an analyst to see exactly what the code is doing on any given instruction.

Using VEHs for this purpose is nonstandard behavior for benign programs, so its very presence is a weak heuristic for maliciousness, and a stronger indicator of Dridex, since it has used the VEH technique for some time. However, the analyst notes, while the VEH code is definitely the same in both Dridex and Entropy, “weirdly, I am *not* seeing that code being used by Entropy.”

Entropy string decoding and API resolving subroutines

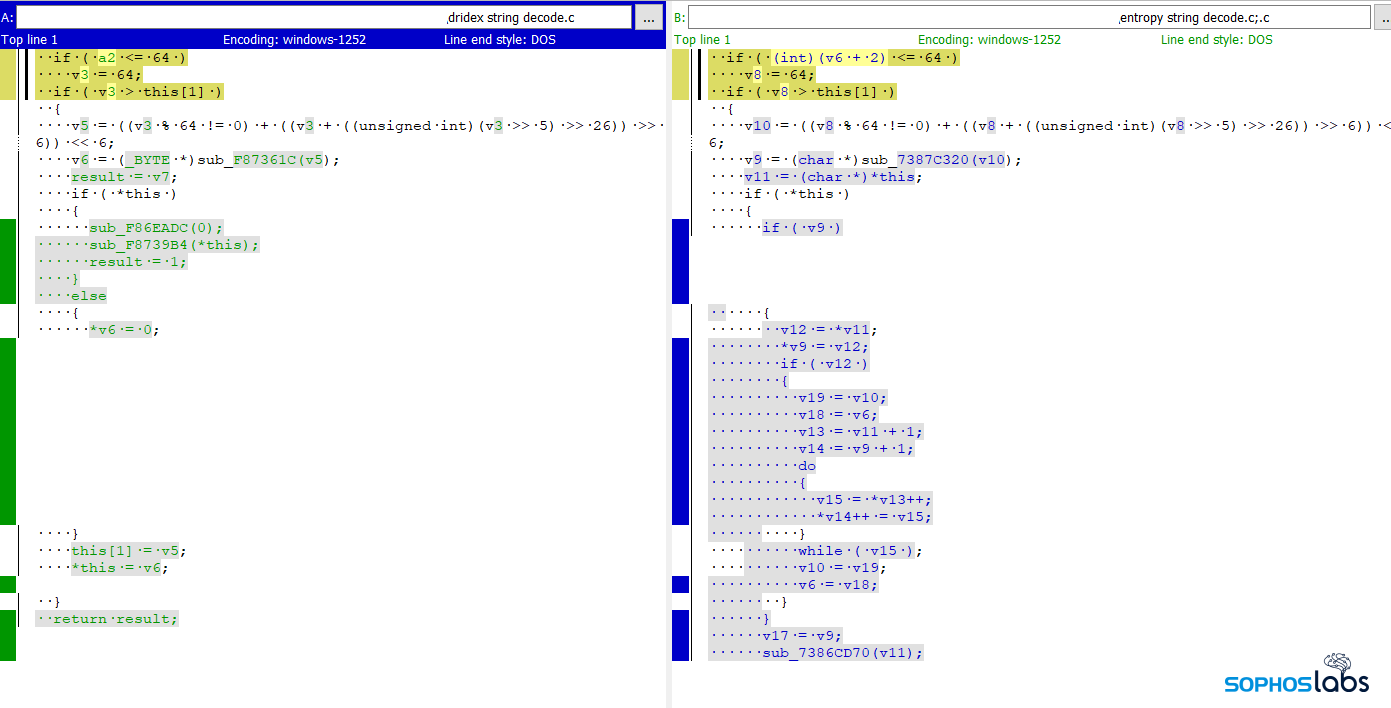

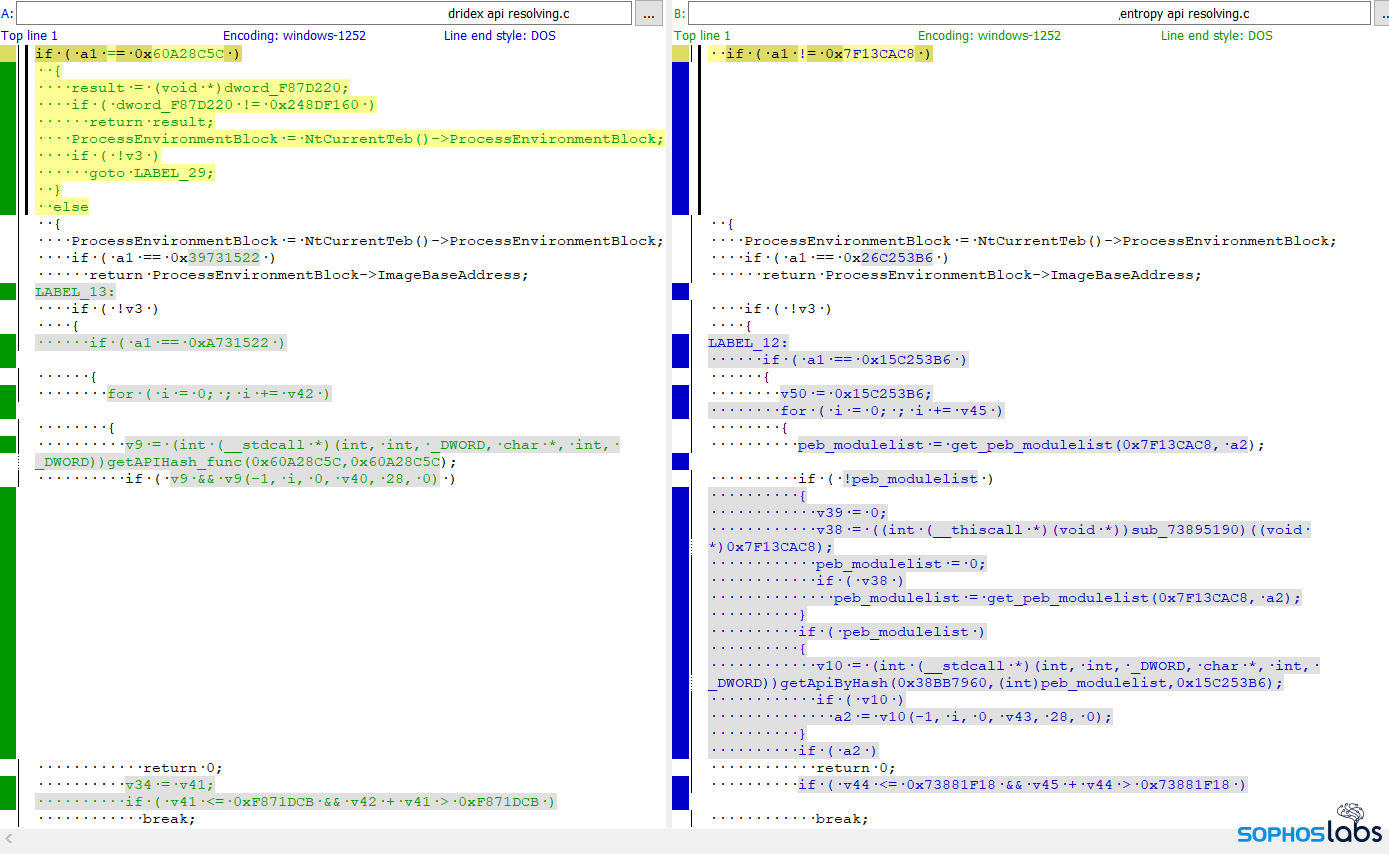

We also looked at two other aspects of the ransomware’s behavior and compared it to similar subroutines found in Dridex. One of these subroutines is used to decode encrypted strings embedded in the malware.

In this side-by-side comparison, the Dridex form of this subroutine appears on the left, and the Entropy form appears on the right. The analyst who looked at these examples had to significantly clean up the code in order to produce this side-by-side comparison. They described the string decryption logic as fundamentally similar code flow and logic, but “with a bit of optimization” in the Entropy version.

Likewise, the analyst compared the source code for subroutines Dridex and Entropy use to resolve API calls. While there are small differences (Dridex takes two hash values as input, while Entropy only takes one), the analysts say the logic for “walking” (navigating through every available API) then parsing the Process Environment Block (PEB) and modulelist, looks remarkably similar.

In summary, this behavior of walking the structures to get the base DLL name, and eventually their function addresses — using PEB_LDR_DATA and LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY — is a behavioral trait shared by both Entropy and Dridex.

Another notable detail, almost too insignificant to mention, is that the decrypted strings from the ransomware contain a line of text that starts with the targeted organization’s name, followed by “…falls apart. Entropy Increases.” This doesn’t appear in the ransom note, or anywhere else, only inside the binary. This appears to be a reference to a line in the 2005 young adult fiction novel Looking For Alaska by John Green: “Entropy increases. Things fall apart.”

Detection and guidance

In both cases, the attackers relied upon a lack of diligence – both targets had vulnerable Windows systems that lacked current patches and updates. Properly patched machines, like the Exchange server, would have forced the attackers to work harder to make their initial access into the organizations they penetrated. A requirement to use multifactor authentication, had it been in place, would have created further challenges for unauthorized users to log in to those or other machines.

Entropy ransomware infections were preceded by detections of Cobalt Strike beacons (ATK/Tlaboc-A), Dridex malware (Mal/EncPk-APX, Troj/Dridex-AIZ), and the batch scripts (Troj/Agent-BCJY) that were eventually used to spread the ransomware to other machines. The ransomware components are detected a number of ways: in memory, behaviorally, and by the static detection of the runtime packer.

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge the contributions of Anand Ajjan, Colin Cowie, Abhijit Gupta, Steven Lott, Rahil Shah, Vikas Singh, Felix Weyne, Syed Zaidi, and Xiaochuan Zhang to our analysis of Dridex and Entropy, and the attackers’ methodology.