There’s a famous and very catchy song that starts, “It was 20 years ago today…”

But can you remember where you were and what you were doing 20 years ago, if you’re old enough to have well-formed memories of that period?

If you were in IT or cybersecurity 20 years ago this week, the answer to that question is almost certainly a big fat “Yes.”

That’s because July 2001 is when the infamous Code Red computer worm showed up, spread fast, and all but consumed the internet for several days.

I can certainly remember where I was, because I had just – only just! – relocated from Sophos UK to Sophos Australia, where we were in the process of opening up a new threat research lab.

I’d had just enough time to figure out how to use Sydney’s buses and trains (there were no Opal cards back then – bus travel was based on magnetic strips and unintiutive “zone numbers” that turned out to be old British miles in disguise).

On Code Red day, I got to the office nice and early, ready for the sort of problems often left behind on purpose handed over carefully by those of our colleagues in North America who been the last to leave their office.

I was the second person into work that day, and I was greeted by a early-bird colleague who was wearing one of those conflicted excitement/fear/resignation expressions that, in the late 1990s and early 2000s world of IT, could only mean one thing.

WILDCAT VIRUS OUTBREAK!

He very calmly advised me to attend to all my bodily needs right away: get coffee and any needed snacks; take a toilet break (at that office, the bathrooms were out in the fire escape and down the stairs a fair way, for some reason); adjust desk and chair for long-term comfort; find most ergonomic alignment of keyboard; optimise colour settings for screen (computer displays really weren’t that good 20 years ago).

“I think we might be here for a while,” he said. (We were. I can’t remember if the pub next door had already closed by the time I went home, but it might as well have, and I am pretty sure I was the only passenger on the bus.)

Code Red wasn’t a new idea.

Indeed, it used one of the tricks of the notorious Internet Worm from way back in 1988: a stack buffer overflow in server software that was almost certainly open to the internet on purpose.

In Code Red’s case, the vulnerable service was IIS, Microsoft’s unfunkily but informatively named web server, Internet Information Services.

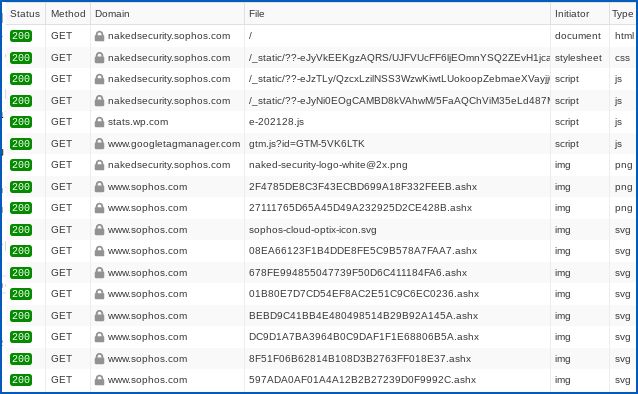

By sending in an innocent-ish HTTP GET request, which is the unexceptionable way that almost every browser asks for almost every page on almost every website, the Code Red malware was able to distribute itself…

…all in a single HTTP request.

The malicious malware “probe” that drove the Code Red infection process consisted of:

- Making a TCP connection to port 80 on a randomly chosen computer. Back then, only a few websites used HTTPS, which runs on port 443.

- Sending a GET request that asked for an unusual URL. The URL looked something like this:

GET /default.ida?NNNN[...]NNN%u9090%u6858%ucbd3%u7801%u9090%[...]. - Following the request with an HTTP body that included further malware code. Code disguised as data is known in the jargon as shellcode.

The malware didn’t need to bother about whether the connection failed, or whether the computer really was a web server, or even if there was a computer at the other end at all.

It didn’t need to download or install any additional files, make any registry changes, wait for a user to open or click anything (or even for any user to be logged in), write anything to disk, or take any notice of what the server sent back if the connection succeeded.

In modern jargon, this was a truly fileless 0-click remote code execution exploit in action.

In case you’re wondering, the long string NNNN[...]NNNN in the GET> request was sized up to be just too big for the buffer awaiting it in the IIS server.

The resulting buffer overflow lined up the hexadecimal-encoded data in the fake URL with the return address on the CPU stack to which IIS would jump back after receiving the request.

A return address overwrite of this sort misdirects the flow of execution at the end of the current code subroutine (or function, in C jargon) to a memory location of the attacker’s choice.

The important hex digits above are %ucbd3%u7801, two 16-bit numbers that decode in memory to the little-endian binary string D3 CB 01 78, which represents the 32-bit number 0x7801CBD3.

(In little-endian format, numbers are stored with least significant byte at the lowest address, so that they come out in the opposite order to our usual numeric notation, as though they were written right-to-left while everything else goes left-to-right.)

Back in the day

Back in 2001, Windows didn’t support ASLR, short for Address Space Layout Randomisation, so any DLLs loaded on your computer would show up at the same address as they did on mine, and indeed on everyone else’s.

This predictability in memory arrangement made remote code exploits based on stack buffer overflows almost trivial to figure out in those days.

You just had to pick a return address for your stack overwrite that corresponded to a useful sequence of instructions anywhere in any Windows DLL that you would expect to be in memory already.

In this case, the attackers knew (or, more precisely, could assume with high probability) that memory address 0x7801CBD3 would be somewhere safely inside MSVCRT.DLL, the Microsoft Visual C Runtime library.

This DLL is used by many Windows programs, including IIS, so the virus writers could predict that the binary data at the given address would be the machine instruction CALL [EBX].

The crooks also knew, at that point, that the EBX register just happened to hold the address of another memory location on the stack that had also been modified in the buffer overflow, so that the CPU diverted execution directly back into the bytes submitted in the GET request.

Those bytes contained code that located the address in memory of the HTTP request body, which contained yet more attacker-supplied shellcode, and jumped there.

Back in 2001, Windows didn’t support DEP, short for Data Execution Prevention, so that any code shoved onto the stack could blindly be executed, even though the stack is intended to store data, not code.

This lack of execution prevention on the stack meant that remote code exploits didn’t need to find sneaky places in memory to locate themselves, and were therefore trivial to figure out.

What, no canary?

Also, few if any programs in those days bothered to use what’s known as a Stack Canary, or a stack-smashing protector, which acts as an early warning that a stack overflow has just occurred.

A stack canary is a randomly chosen value placed onto the stack when a subroutine gets called, so it occupies the memory bytes just in front of the return address.

This canary is checked by the called subroutine in the last line of code before it executes the RET instruction to return to the caller.

This helps to spot buffer overflows, because an attacker has to overwrite all the bytes leading up to the return address in order to overflow far enough to reach the return address.

The attacker can’t easily guess what value to put in the buffer overflow data at the point where the canary lives, so the canary will probably get overwritten by incorrect data and the canary check will therefore fail.

At this point, with very little additional code added to each protected function, the operating system can instantly terminate the offending program before the return address hijack takes place.

Guessing made easy

All this predictability made stack overflow exploits really easy to figure out 20 years ago:

- The layout of common system functions in system DLLs could trivially be predicted. Attackers could easily and reliably find good return address overwrite candidates.

- Shellcode could simply be placed directly on the stack as part of the buffer overflow. Stack shellcode would almost certainly be allowed to execute, even though there was no legitimate need for it to do so.

- The stack layout could trivially be predicted, with no protective “canary” values. Attackers could attempt stack smashing attacks without worrying about getting noticed.

As we said in this week’s podcast:

In the Code Red days, […] if you could find a stack buffer overflow, it was often very, very little work, maybe half an afternoon’s work, to weaponise it, to use the paramilitary terminology that cybersecurity seems to like, and turn it into a workable exploit that could basically break in on any similar Windows system.

The silver lining, if there was one, is that Code Red wasn’t programmed to do much damage to the computers it infected.

The direct damage was limited to an attempt to deface your website with a “Hacked by Chinese” message, although there was no evidence that the malware itself came from China.

But Code Red didn’t go after anything else of yours, such as searching for your passwords or your trophy data, or scrambling all your files and demanding money to unlock them again, as you might expect from today’s cybercrooks.

Once running, Code Red dedicated 99 parallel threads of execution to generating a list of new victim computers and spewing out HTTP requests to all of them.

That network-based aggression alone was how it came to cause as much disruption as it did.

What can we learn from Code Red?

Amusingly (well, it’s worth a smile with hindsight), Microsoft had patched against the Code Red buffer overflow exploit about a month before the attack.

But with many companies struggling to get patches done within a month even in 2021, you can imagine how few people had installed the vital patch in time back in 2001.

And anyway, even if you were patched, or weren’t running IIS at all, sooner or later you’d end up facing a barrage of infection attempts from servers that hadn’t been patched and were now actively infected (or, of course, re-infected).

That’s an important reminder that, in cybersecurity, an injury to one is an injury to all.

To mix a metaphor, one rotten apple really can spoil the barrel,

You need to patch not only for yourself, but also for everyone else as well:

If nothing else, just in terms of network traffic, [Code Red] was quite disastrous. […] A huge percentage of network traffic in the world was this jolly thing trying to spread from anyone who’d got infected to thousands, millions, of other computers. […] Even if you’d patched, you’d still get these packets battering on your web server, like a built in DDoS.

Another important lesson to remember is that uncontrolled cybersecurity “experiments” and irresponsible disclosure are something that we can all do without.

Again, from the podcast:

Q. So, when you’re analysing this, when it’s breaking out, what’s your mindset? Are you [thinking], “This is unique”? […] Are you impressed by it?

A. You have to have a little bit of grudging respect. “My gosh, they packed so much into so little.” At the same time, when you look at the code, you think, “You knew! When you said, ‘Let’s have 99 threads,’ when you said, ‘Let’s try and spread everywhere, all the time,’ you’d made your point already.”

To go and make it an extra 20 times is excessive. To make it another 1000 times is really going over the top. To go and do it another 1000,000,000 times? Well, it’s hard to have much respect for that. And that’s all I’m saying.

.

What to do?

- Patch early, patch often. Do it for the rest of us, even if you don’t feel you need to do it for yourself.

- Be circumspect when you want to prove a cybersecurity point. Responsible disclosure will earn you not only hacker kudos (and often a financial reward as well), but also respect from the greater IT community for not putting them in harm’s way in the name of research.

- Embrace cybersecurity improvements in your coding. The defences mentioned above (DEP, ASLR and stack protection) aren’t perfect, but they are examples of technologies popularised by malware like Code Red because they make exploits harder to find for the crooks.

By the way, despite their simplicity and effectiveness, it took years for the protections mentioned above to become ubiquitous in Windows software products.

Don’t be slow to seek out improvements that push back even further against the crooks, even if it means revisiting legacy code you thought was “feature complete” by now.

LISTEN NOW: CODE RED IN THE NAKED SECURITY PODCAST

Code Red section starts at 12’50”.

Click-and-drag above to skip to any point in the podcast. You can also listen directly on Soundcloud.

Beamer

What? No shout-out in this article to Marc Maiffret, who discovered and named Code Red? His story, and why he named the worm Code Red, deserved at least a mention.

Paul Ducklin

Apparently, it was named after some leftover Mountain Dew soft drink (Code Red flavour?) that the researchers found in the canteen when there was no one else to turn to for sustenance. (That doesn’t mean much to me. I’ve never even seen Mountain Dew, let alone tasted it, in any of its incarnations. It’s a North American thing, it seems. I’ve always known of Code Red in association with “snow alert”.)

Anyway, there are numerous people whose names could be included in the Code Red story. But their contributions have been variously and widely described elsewhere, including in their own words, so I’ll leave them all to speak for themselves.

After all, this article is more about “What we can learn 20 years on,” as the headline says.

If I were to name any of the people who worked on it during the early days of the outbreak, I’d get someone saying, “But you didn’t mention Y,” or “What about Z?”, or “X didn’t deserve all the credit you gave them,” and so on. So this is merely a sort of recollection, not an attempt to write a precise history of the malware and the work it spawned, to produce a biography of any of the people whose names are associated with the immediate aftermath of the outbreak, or an attempt to assign “research points” to anyone in particular.

Dealing with Code Red and its aftermaths was ultimately a huge and global team effort, like many or most of history’s big virus outbreaks. Anyone who was doing IT support around that time almost certainly did their bit (and probably took the last bus home from a long-shuttered pub). A shout out to them all!

BillH

I remember this like it was yesterday. Many student run labs in my building never got the idea that AV was necessary and had to be renewed yearly to get updates. Because of my position, I was able to unplug infected computers until they got remediated. Campus networking folks cut off buildings when the height of Code Red hit.

Paul Ducklin

When you say “because of my position”, do you mean:

[A] Job position (e.g. person in charge at the time).

Or:

[B] Physical location (e.g. person standing in front of patch panel in server room).

Or, very best of all if you can swing it:

[C] Both A and B.

:-)

James Gillespie

Code Red also had a secondary effect where it swamped port 80 on our HP web managed printers causing them to stop responding. The printers would work for a while after power cycling, but eventually stop responding again. I suspect any port 80 web managed network attached device would have been susceptible.

Laurence Marks

> The crooks also knew, at that point, that the EBX register just happened to hold the address of another memory location on the stack that had also been modified in the buffer overflow, so that the CPU diverted execution directly back into the bytes submitted in the GET request.

The jump back into the buffer overflow data didn’t have to be precise. Intel instructions are of variable length, from one byte to five or more. If you jump (misaligned) into the middle of an instruction, the instruction fragment is interpreted as something completely different, as are subsequent instructions. The Code Red author avoided this problem by packing the code with a bunch of 0x90 codes, This is the one-byte No-op instruction. It tells the computer “Do nothing, Just go on to the next instruction. Because it’s only one byte, it’s always safe to jump into the middle of a sequence of these. The computer will churn through those and meet the real code properly aligned.

Note the 90s in the GET sequence posted above:

> GET /default.ida?NNNN[…]NNN%u9090%u6858%ucbd3%u7801%u9090%[…]

(%u9090 is merely a compact way of expressing %90%90)

Paul Ducklin

In the jargon, a string of one-byte instructions that exists as a landing zone for an exploit is known as a nop sled. Because you slide down it into the real code.

Intriguingly, NOP (0x90) is actually the encoding of the instruction XCHG RAX,RAX (a one-byte instructions which swaps the RAX register with itself), which actually doesn’t strictly “do nothing”, but it does achieve nothing :-)

Curious

How is %u9090 more compact than %90%90? They are both 6 in length, no?

Paul Ducklin

I always assumed that the malware author used the 16-bit form (%u encoding) because it swapped round every pair of bytes so that the hex numbers didn’t appear in the URL in the same order that they would do in memory.

Perhaps some web filters of the time would decode such strings incorrectly by failing to swap the big-endian UCS-2 (double-byte) characters into little-endian sequences?

It seemed somewhat pointless at the time, at least for anyone doing what we might today call “threat hunting”, given that the presence of all those “90” bytes and the giant string of “NNN…NNN” can only really mean one thing… shellcode!

RichardD

“… just too big for the buffer awaiting it in the ISS server …”

Wow – they managed to infect a server in space! :P

I assume you meant “IIS”, not the international space station.

Paul Ducklin

Hahahahahaha, fixed it, thanks. I guess a buffer overflow on the ISS would be a payload that wouldn’t fit into the airlock.

FWIW, it seems that computer viruses *have* been reported on the ISS, though not via IIS as far as I know:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2008/08/27/computer-worm-strikes-international-space-station/

Maxim Weinstein

Yeah, this one certainly brings back memories, and not happy ones. I was one of a very small IT team at a company that created performance testing software for websites. You can imagine, then, how many engineers we had running IIS… on production servers, on demo laptops, on their primary PCs, etc. It really was like a game of Whack-a-Mole: Sniff the network, identify an infected machine, figure out who it belongs to, track them down, shut down IIS, update AV, rinse, repeat.

Paul Ducklin

“How DARE you shut down my development server! I was using that! How DARE you patch my development server! I was testing legacy code on that! How DARE you install anti-virus softare on my development server! I was testing some hacking tools on that server! How DARE you make me move my test computers off the live company network! I read my email while I’m waiting for my tests to finish! How DARE you try to [CLACK] hello? hello? anyone there? it’s gone very dark? was that a circuit breaker tripping? is there a power outage of some sort? hello? HELLLLLLLOOOOOO?”

Robert Howard

we noticed it first when our checkpoint firewalls started to crash from all of the internal windows servers trying to send out http requests to the internet subnets. when I kept looking at the top ten talkers they were all only windows servers. we started to segment the networks to reduce the traffic and later found out we got infected via a single windows server connected with a modem to hotmail It used the index server to obtain all of the other local windows servers and just kept going. Better patching regiments would have stopped this attack on us. Still remember it well. Less knowledgable people at the time wanted SUN to come in and repair the workstations “since that was clearly the real problem”.