Editor’s note: This is one of a series of articles focused on the Conti ransomware family, which include a detailed analysis of a Conti attack, A Conti Ransomware Attack Day-By-Day, and a guide for what IT administrators can expect when Conti ransomware hits.

For the past several months, both SophosLabs and the Sophos Rapid Response team have been collaborating on detection and behavioral analysis of a ransomware that emerged last year and has undergone rapid growth. The ransomware, which calls itself Conti, is delivered at the end of a series of Cobalt Strike/meterpreter payloads that use reflective DLL injection techniques to push the malware directly into memory.

Because the reflective loaders deliver the ransomware payload into memory, never writing the ransomware binary to the infected computer’s file system, the attackers eliminate a critical Achilles’ heel that affects most other ransomware families: There is no artifact of the ransomware left behind for even a diligent malware analyst to discover and study.

That isn’t to say there aren’t artifacts and components to look at. The threat actors involved in attacks using Conti have built a complex set of custom tooling designed not only to obfuscate the malware itself, when it gets delivered, but conceal the internet locations from which the attackers have been downloading it during attacks, and prevent researchers from obtaining a copy of the malware that way as well.

Two-stage loading process

The first stage of the Conti ransomware process involves a Cobalt Strike DLL, roughly 200kb in size, that allocates the memory space needed to decrypt and load meterpreter shellcode into system memory.

The shellcode, XORed in the DLL, unfurls itself into the reserved memory space, then contacts a command-and-control server to retrieve the next stage of the attack.

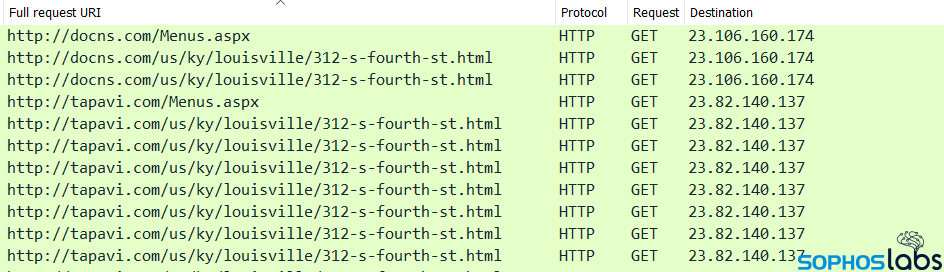

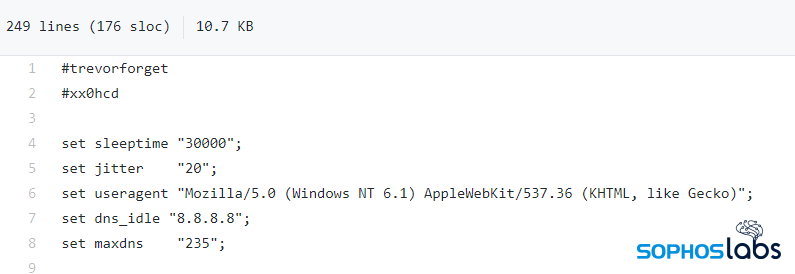

This C2 communication is distinctive for a number of reasons. First, the malware appears to be using a sample Cobalt Strike configuration script named trevor.profile, published on a public Github archive. The profile serves as a sort of homage to an incident in which security researchers attending a conference found an insect in a milkshake at a restaurant outside the conference center.

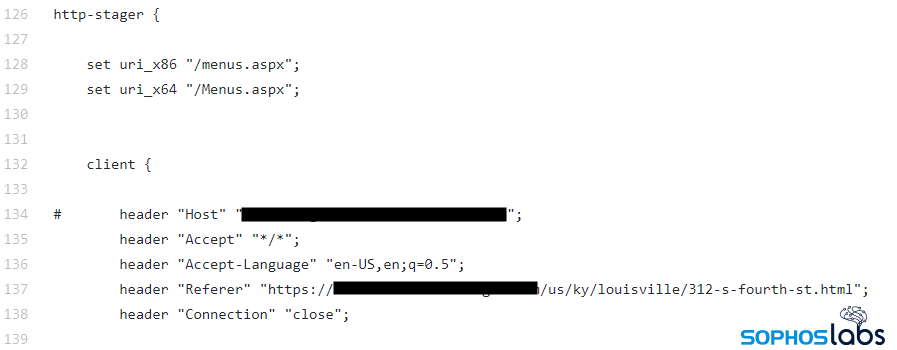

But it doesn’t appear that the Conti attackers have modified this sample script very much, which makes the C2 communication notable in two ways: The script designates certain characteristics used during this phase of the attack, including a User-Agent string (“Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko)“) that mimics that of a computer running Windows 7 but, distinctively, fails to identify the specific browser; and a static URI path (“/us/ky/louisville/312-s-fourth-st.html“) that includes the address of the infamous restaurant where the researcher discovered the bug in their shake.

The initial connection to the C2 server is to a page named Menus.aspx on the server; That page delivers the next payload, which the first one loads into memory — another Cobalt Strike shellcode loader that contains the reflective DLL loader instructions.

If that works successfully, the malware then contacts the “312-s-fourth-st.html” page on the same C2 server. The attackers only trigger these chains of events during an active attack, placing the ransomware binary on the C2 server so that it can be retrieved by this process only while the attack is ongoing, and removing it immediately afterwards.

Elusive ransomware payloads

Because of the ephemeral nature of the placement of the ransomware payload, analysts had difficulty obtaining samples for research. But we were able to salvage some of the in-memory code from infected computers where the malware was still running.

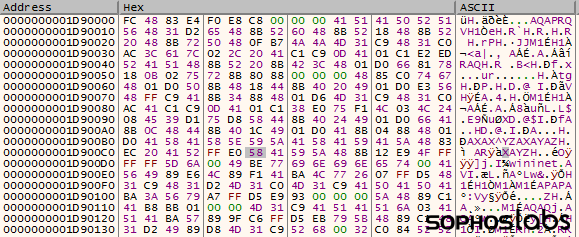

The ransomware process is not particularly unique, but it does reveal the ransomware creator’s ongoing interest in thwarting analysis by security researchers.

The ransomware itself uses a relatively common anti-analysis technique sometimes referred to as “API-by-hash,” in which Conti uses hash values to call specific API functions; Conti has an added layer of encryption over the top of these hashes to futher complicate the work of a reverse engineer. The malware has to perform two cycles of decryption on itself in order to perform those functions.

Among the behavior observed by responders, the ransomware immediately begins a process of encrypting files while, at the same time, sequentially attempting to connect to other computers on the same network subnet, in order to spread to nearby machines, using the SMB port.

Conti’s developers have hardcoded the RSA public key the ransomware uses to perform its malicious encryption into the ransomware (files are encrypted using the AES-256 algorithm). This isn’t unusual; It means that it can begin encrypting files even if the malware is unable to contact its C2.

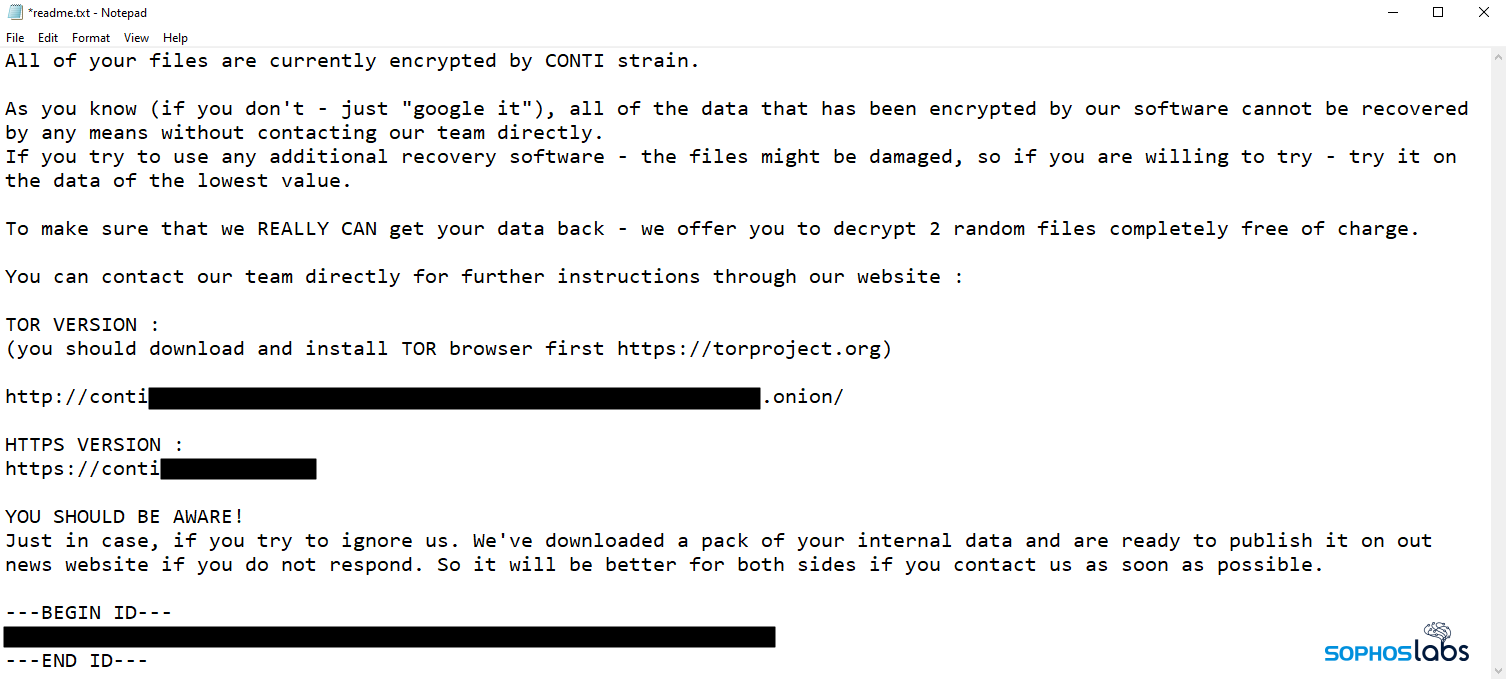

Unfortunately, that isn’t the only threat this ransomware poses to its targets: Conti ransomware has also adopted a “leaks” site like several other ransomware threat actor groups. The attackers spend some time on the target network and exfiltrate sensitive, proprietary information to the cloud (in recent attacks, the threat actors have used the cloud storage provider Mega).

Under a header labeled YOU SHOULD BE AWARE! , the ransom note threatens, “Just in case, if you try to ignore us. We’ve downloaded a pack of your internal data and are ready to publish it on out (sic) news website if you do not respond. So it will be better for both sides if you contact us as soon as possible.”

Detection guidance

Conti ransomware, on its own, is unable to bypass the CryptoGuard feature of Sophos Intercept X; Our endpoint products may detect components of Conti under one or more of the following definitions: HPmal/Conti-B, Mem/Conti-B, Troj/Swrort-EZ, Troj/Ransom-GEM, or Mem/Meter-D. Network protection products like the Sophos XG firewall can also block the malicious C2 addresses to prevent the malware from retrieving its payloads and completing the infection process.

Indicators of compromise for malware samples examined in this research has been posted to the SophosLabs Github.