In September, a new ransomware brand emerged just as the Maze ransomware gang began shuttering its operation. Named Egregor (from an occult term derived from the Greek word ἑγρήγορος, “wakeful”—a term used to refer to an angel-like spirit or group mind), the ransomware leverages data stolen during the attack to extort the victim for payment, following a trail blazed by Maze.

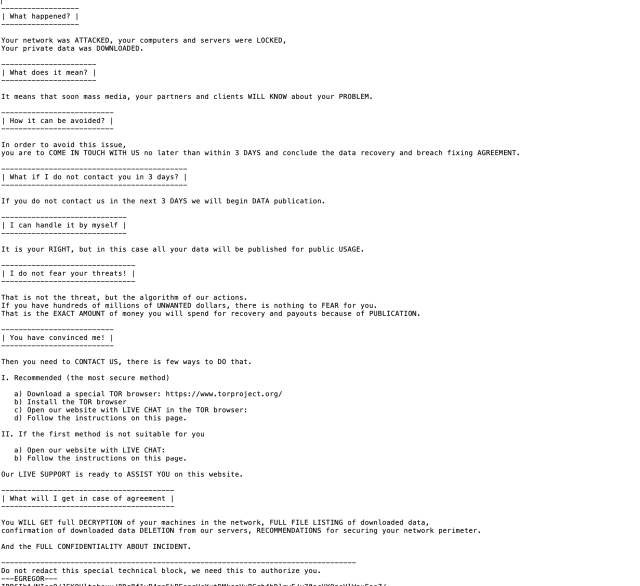

Egregor’s ransom note tells its victims “soon mass media, your partners and clients WILL KNOW about your PROBLEM…If you do not contact us in the next 3 DAYS we will begin DATA publication.”

Like Maze, Egregor uses the ChaCha and RSA encryption algorithms to encrypt victims’ files. Also like Maze, Egregor is suspected to be a ransomware-as-a-service operation—dependent on affiliates who receive payment for dropping the malware on victims’ networks.

But Egregor’s code is not a derivative of the malware used by Maze; rather, it is a variant of a ransomware family known as Sekhmet. Sekhmet’s operators started publishing data from victims in March 2020, but their “Sekhmet Leaks” website is no longer accessible, and only six victims were publicly exposed by the ring before the site went down—which coincided with the launch of the Egregor site. It’s not clear if the creators of Egregor and Sekhmet are the same, but Egregor’s ransomware is clearly derived from the Sekhmet malware.

We first detected Egregor in September during an attack against a customer. As of November 25, the ring has posted details on over 130 victims on its Tor hidden services (.onion) website. The alleged victims of these attacks are diverse, both in terms of location and organization type—they include schools, manufacturers, logistics organizations, financial institutions, and technology companies. The Egregor gang specifically called out two gaming companies—Crytek and Ubisoft—in a “press release” in October.

The spirit descends

Commodity malware is the vehicle most commonly associated with Egregor. Some of the attacks we’ve tracked were linked with Qbot malware activity, though it was not clear how long Qbot had been present on the victims’ networks. Qbot (also known as Qakbot) deploys from a malicious document file attached to an e-mail message. Earlier this year, ZDNet reported that Qbot’s operators engaged in “thread hijacking,” sending the maldocs as replies to ongoing email threads in order to dupe targets into opening the malicious attachments.

Egregor has no way to spread itself, so it requires the attackers to move laterally themselves, using built-in Windows capabilities and other exploitation tools. In some cases, Cobalt Strike exploitation tools have been detected as part of Egregor attacks. The attacker(s) used these tools to execute scripts, gather information about other systems on the network, extract additional credentials, and spread the ransomware. In one case, the Cobalt Strike agent was used to create an RDP connection to other machines on the targeted network, and copy the Egregor executable to them—copying the files to the directory C:\perflogs.

In the same attack, another malware called SystemBC—a Tor network proxy—was used to create an obfuscated backchannel for data exfiltration and attack communications. The use of Cobalt Strike, SystemBC and the C:\perflogs directory in this case match the behavior seen in a Ryuk attack we investigated in September 2020. (We’ve also seen Cobalt Strike tools used in connection with earlier Sekhmet attacks.)

After exfiltrating data, the attackers launch the ransomware. The approach to launching the ransomware varied across the incidents we examined; in some cases, it was launched by a script, and in others it was configured as a scheduled Windows task.

As with Sekhmet, the Egregor ransomware itself is not an executable, but a dynamic link library (DLL) that is executed using Windows’ rundll32.exe utility. To evade sandbox detection, the DLL will only execute when given a password as a command line parameter, along with a flag for the type of the attack to be executed. We’ve seen three different passwords used in attacks we investigated, in addition to other parameters:

rundll32.exe C:\Windows\sed.dll,DllRegisterServer -passegregor1313 --full rundll32.exe /i C:\WINDOWS\b.dll DllRegisterServer -passegregor9999 --full --fast=256 rundll32.exe C:\perflogs\clang.dll,DllRegisterServer -peguard6

The DLL is a two-stage package. The first stage is an unpacker that verifies the password is correct by checking against its SHA256 value. The second stage is the actual decrypted ransomware DLL, which contains the ransom note format, along with a hardcoded RSA key and list of files and process names to kill or terminate. There’s also a number of “spaghetti” functions included for the purpose of deterring analysis of the code.

Paying the piper

Once Egregor executes, it encrypts a wide variety of data files, including images, videos, documents, SQL and other database-related files, Web pages, JavaScript files, and executables. Encrypted files have their names appended with an extension made up of random characters. As with Sekhmet, the ransomware drops a ransom demand in a text file named RECOVER-FILES.txt:

The “special technical block” at the end of the ransom note is unique to the victim. Following the note’s instructions to connect via a Tor browser or via a public internet to the Egregor web portal, which instructs victims to upload their RECOVER-FILES.txt file.

From there, victims can engage with Egregor’s “customer service” organization to receive the ransom demand and negotiate payment.

More of the same

The use of crafted spam messages with malicious attachments, commodity malware and exploitation tools, and exfiltration of data for extortion purposes have become common tactics as ransomware developers have shifted to an “as-a-service” model. These threats require a defense in depth to prevent theft and encryption of data, including educating employees on the tactics that might trick them into executing the malware that gives ransomware attackers their foothold on the network.

Given that the group behind Egregor claims to sell stolen data if ransoms are not paid, it’s not enough to have good backups of organizational data as a mitigation for ransomware. Organizations need to assume that their data has been breached if they suffer an Egregor (or any other ransomware) attack. Blocking common exfiltration routes for data—such as preventing Tor connections—can make stealing data more difficult, but the best defense is to deny attackers access through email attachment malware and other common entry points.

Malware protection throughout the organization can help prevent commodity malware attacks such as Qbot, and lateral spread through tools such as Cobalt Strike. (Sophos detects Egregor in multiple ways, and also detects Cobalt Strike and Qbot, as noted in the indicators of compromise posted on SophosLabs’ GitHub.)

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge the contributions of Anand Aijan, Gabor Szappanos, and Mark Loman to this report, as well as Peter Mackenzie, Syed Shahram, Bill Kearney, and Sergio Bestulic of Sophos MTR’s Rapid Response team.