If you nearly didn’t read this article because you thought the headline sounded like a story you could take for granted, as you would if you saw an article called “Dinosaurs Still Extinct” or “Sun to Rise in East”…

…then be aware that we nearly didn’t write it for the same reason.

Bugs and vulnerabilities in built-down-to-a-price devices made for kids are, very sadly, not a new or even an unusual problem.

However, according to the Norwegian cybersecurity researchers who analysed the XPLORA 4 watch described below, the company that sells it claims to have close to half a million users, and annual revenues approaching $10,000,000.

So it seems that writing up smartwatch security blunders is still important, because these devices are steady sellers despite their erratic cybersecurity history.

You can see why kids’ smartwatches are popular.

Getting your first watch after learning to tell the time is still a delightful childhood rite of passage, at least in countries where watches are affordable.

And a smartwatch helps families kill three birds with one stone.

Firstly, for the kids, it’s a watch! You can tell the time all by yourself! It’s a fashion statement! (And it means you no longer have an excuse to be late any more, but that’s a realisation that only dawns after you’ve adopted the watch into your own lifestyle and aren’t going to give it up lightly.)

Secondly, it’s not just an old-fashioned watch, because it’s cool and modern enough to slot right into our contemporary, connected world.

Thirdly, for the parents, it’s an emergency lifeline that their own parents never had but would probably have welcomed if they did.

After all, smartwatches can help you keep track of your kids when they’re off on their own, so you no longer need to get frantic with worry whenever they don’t show up on time.

The creepiness factor

Unfortunately, smartwatches that can track your kids have a creepiness factor that the wind-up wristwatches and simple battery-powered LCD timepieces of yesteryear simply didn’t have.

That’s because most smartwatches keep track of where you are via some sort of internet service that requires always-on (or almost-always-on) network access.

This means that even budget smartwatches usually include mobile phone connectivity; they often run a full-blown, albeit stripped-down, mobile phone operating system such as Android; and they regularly make network connections that permit two-way communications.

Those network connections can be used not only to upload and store tracking data to the vendor’s cloud servers, but also to download updates and commands.

So there’s a lot that could go wrong, even in a childrens’ smartwatch programmed with the most noble aims, and thereby put the privacy of your kids and your family at needless risk.

The irony of buying a watch to improve your child’s safety only to find that it simultaneously reduces their security is not lost on the researchers who wrote up the findings we’ll be covering here.

Harrison Sand and Erlend Leiknes of mnemonic, a Norwegian cyberthreat response company, worked with the Norwegian Consumer Council on cybersecurity in smartwatches back in 2017 for a report entitled #WatchOut – Analysis of smartwatches for children, so they’ve been there before.

This year, they decided to revisit the latest model of one of the smartwatch brands they looked at last time:

Since the [2017 report], [Norwegian smartwatch vendor] Xplora is emerging as one of the leaders in their geographical markets, and expanding into new territories. With this in mind, we thought it was a worthwhile endeavor to look at their updated model, the XPLORA 4. In our previous assessment, our scope and focus was limited to the communication between the watch and the local servers, and the parental application. This time around decided to take a deeper look at the watch itself.

We’re not going to explain in detail how the researchers performed their task – for that we recommend you read their report yourself.

It’s very well-written – it’s non-technical enough that you don’t need to be an experienced reverse engineer or Android coder to follow what they did, but it has sufficient detail to act as an excellent guide if you would like to get started in Android cybersecurity spelunking yourself.

What they found

In brief, the researchers:

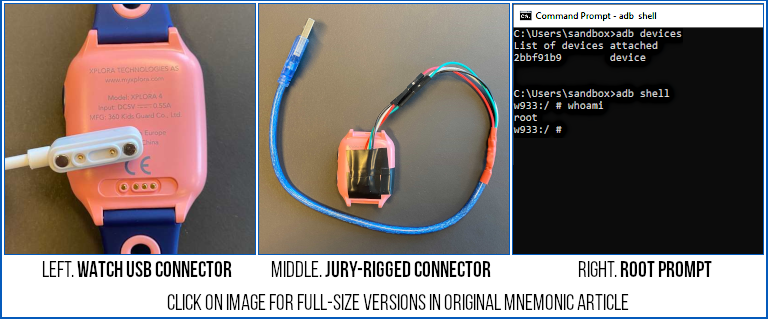

- Rigged up a USB cable that would connect to the proprietary connector on the watch.

- Used an already-available software tool to download the firmware from the device.

- Modified the firmware to enable root-level (administrator) access over USB.

- Uploaded the modified firmware back to the device.

- Connected using ADB (short for Android Debug Bridge), the standard tool for USB access.

- Got a root shell on the device.

Root, as you probably know, is pretty much to Linux and Android what Administrator and SYSTEM rolled into one would be for Windows.

With a root-level command prompt, the researchers were able to explore the operating system and Android apps on the watch, and quickly discovered an package called Persistent Connection Service.

This app seemed, amongst other things, to be some sort of debugging or system monitoring process that automatically kept track of which programs were running and what control messages they would accept.

Handily, the Persistent Connection Service wrote a debug trail that identified these processes and their supported control messages, so the researchers quickly noticed numerous fascinating lines in the debug log, which is helpfully sent over the USB connection via adb.

Example debugging output shown in the paper identifies apps and control messages (known in Android as Intents) with highly suspicious names, such as:

134=com.qihoo.kidwatch.action.COMMAND_LOG_UPLOAD

165=com.qihoo.kidwatch.action.REMOTE_EXE_CMD

126=com.qihoo.watch.action.WIRETAP_INCOMING

317=com.qihoo.watch.action.WIRETAP_BY_CALL_BACK

320=com.qihoo.watch.action.REMOTE_SNAPSHOT

303=com.qihoo.kids.smartlocation.action.SEND_SMS_LOCATION

Further analysis revealed that this connection service would itself accept incoming messages via SMS, and use the content of those messages to trigger one of the abovementioned control messages.

Not just any incoming SMS would do, though – the researchers discovered that these “metamessages” (the jargon word we’re using here to describe control messages used to send other control messages) were encrypted with a secret encryption key shared between the manufacturer or vendor and the phone.

Apparently, the secret key is unique to each device, and is programmed into the NVRAM of the watch, some time between when it’s made and when it’s shipped. (NVRAM refers to computer memory that is non-volatile, so it keeps its contents even when the battery goes flat.)

So, the researchers picked one of the more juicy-sounding secret commands shown above, namely REMOTE_SNAPSHOT, and tried to trigger it themselves.

They read the encryption key out of the watch’s NVRAM, constructed their own encrypted control message, and SMSed it to the phone number of the SIM card in the watch.

Busted!

With no visible or audible feedback, the watch snapped a covert picture with its built-in camera and uploaded the image to the vendor’s cloud servers without waiting for any sort of approval.

The researchers didn’t investigate any further, presumably quite reasonably thinking that their point was already well proved, and assuming that the other control messages they discovered did exactly what their names suggested, too.

As they succinctly put it:

[I]n short – an encrypted SMS can be sent to the watch to trigger the surveillance functions.

What next?

Apparently, the researchers supplied the vendor, Xplora, with their findings and Xplora creditably came up with a security patch that was pushed out before the researchers went live with their report.

We couldn’t find any mention of the report or the patch on Xplora’s website or blog, however, so we are relying here on our friends over at Ars Technica, who quoted from a statement they received from the Xplora that stated:

This issue the testers identified was based on a remote snapshot feature included in initial internal prototype watches for a potential feature that could be activated by parents after a child pushes an SOS emergency button. We removed the functionality for all commercial models due to privacy concerns. The researcher found some of the code was not completely eliminated from the firmware.

Xplora also pointed out that any attacker not affiliated with the manufacturer or the vendor of the watch would need physical access to it in order to read out the phone’s copy of the encryption key from NVRAM, plus the phone number from the SIM card, before they could target any specific device.

We haven’t seen the code that handles the encryption, but the mnemonic analysis describes it as using the RC4 cipher, an encryption algorithm with serious flaws that should no longer be used at all, with a 32-bit key, which is well short of current guidelines. So further analysis might have shown that only the watch’s phone number was truly needed for a well-researched attack and that the encryption key could be computed, guessed or inferred.

What to do?

The question “What to do?” is much trickier than usual in a case like this.

Usually, we’d reply, “Patch early, patch often,” but in this case, some parents might not think that patching goes far enough.

After all, there are still two important and unanswered questions:

- Were the other remote commands removed too, such as the worryingly named

REMOTE_EXE_CMDandWIRETAP_INCOMING? - How did those features come to be included in the manfacturer’s firmware in first place?

Or, as the researchers punningly asked, “This is [a set of Intents] that has been created with intent. What exactly is that intent?”

Unfortunately, if you own a smart device, especially one built for children, and it turns out to have baked-in-from-the-start flaws, you may no longer want to trust it at all.

In that case, you have little choice but to stop using it altogether, no matter how much it cost in the first place, and the only advice we can offer is, “Please recycle responsibly.”

Oh, and if you’re a programmer or a software designer, don’t add in undocumented, prototype security “features” just because you think they might be useful in the future.

And don’t use outdated and inadequate cryptography just because you think no one will notice.

Dennis Coburn

Like I’ve said off and on over the last 40 years, “Just because something CAN be done is no reason that it SHOULD be done”. I’ve always been amazed that this concept is not a permanent part of engineering and computer science education.

Paul Ducklin

These days, the rule is more like “just because it CAN’T be done doesn’t mean it SHOULDN’T :-)

Roger Tobie

To quote Aldous Huxley, “Oh brave new world that has such people in it.”

Eric Daleboudt

It is always hard to balance security with giving up privacy as is the same with nice tools versus privacy.

When I want to let my phone guide me to the nearest gas station I must allow it to track my whereabouts.

Fitness trackers upload all kind of data to have it analysed by AI

So if your privacy is paramount to you, don’t use smart devices and pay with cash you stole from a bank.

Is it strange that a parent would like to listen in, or see what’s going on.

The question is are we prepared to ignore the temptations given and go on the old school way of trusting our offspring. I fear the world has changed too much, so we can only adapt to it using the new technologies.

Mahhn

Fear is no way to live. Children should be educated and assisted, not trusted. That is what you training them to be – good decisions makers. It’s unreasonable to expect something from someone when they don’t have the experience/understanding to be able to.

Wade B.

As advanced as smartwatches can be, this shows that low-priced models can be a security nightmare. Thousands of no-name, unbranded kids smartwatches are sold on eBay and Amazon on a daily basis. Some have even made their way into US retail stores such as Dollar General or Menards, usually around the holidays. They are positioned as a cheap alternative to the Apple Watch, and from my own personal experiences with them, the apps that you’re required to use with the watches are from questionable Chinese developers that require a LOT of permissions on your phone to even use. And in one case, the required app disappeared from Google Play after about a year, rendering your still fresh smart watch almost useless.

I certainly hope that smartwatches don’t kill off traditional watches. Though they are old-fashioned in comparison to an Apple Watch or Samsung Watch, they have more character and design choices than smartwatches, and they aren’t privacy nightmares either. It’s best to give a young child a basic analog or simple digital watch to start with and if your kid really wants a smartwatch, do your research and find a well reviewed name-brand model that is known to be privacy friendly.

KernelOops

I assume the app disappeared because Google swung the banhammer on it – probably for containing malware or something.

Charles

The “brave new world” line is from Shakespeare, not Huxley, who did quote The Tempest in several places.

Just saying.

Paul Ducklin

And took the title of his famous novel from it, of course. But you are right that the quote is from The Tempest:

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.