In the past few days we received two phishing campaigns – one sent in by a thoughtful reader and the other spammed directly to us – that we thought would tell a useful visual story.

As far as we can tell, these scams originated from two different criminal gangs, operating independently, but they used a similar trick that’s worth knowing about.

The phishing scammer’s three-step

Most straight-up email phishing scams – and you’ve probably received hundreds or even thousands of them yourself in recent times – use a three-stage process:

- Step 1. An email that contains a URL to click through to.

The message might claim to be telling you about an unpaid electricity bill, an undelivered courier item, a suspicious login to your online banking account, a special offer you mustn’t miss, or any of a wide range of other believable ruses.

Sometimes the crooks actually know your name and perhaps even your phone number and your address.

Sometimes the criminals are flying blind and stick to phrases such as “Dear Customer”, “Dear Sir/Madam” or even just “Hello.”

Sometimes they know the name of your electricity provider or bank; sometimes they don’t know but happen to guess correctly; sometimes they fudge the issue by writing some generic text that’s just enough to get your interest.

The email message doesn’t have to say a lot – all it needs to do is catch you at a weak moment so you click the link.

Clicking a phishing link ought to be safe enough on its own, provided you’re careful about what happens next, but it inevitably takes you one step closer to trouble.

- Step 2. A web page where you need to login to go further.

Usually, after you’ve clicked through, there’s a password page, and often it’s a surprisingly good clone of the real thing, created simply by pirating the HTML, images, fonts, stylesheets and JavaScript from the genuine site and installing it somewhere else.

The imposter pages will often be sitting on a legitimate website that’s been hacked to act as a believable springboard for the attack.

Unpatched blogging sites are popular to hack because the crooks can often find somewhere perfectly innocent-looking and unlikely to be noticed, deep in the directory structure of the real site where a few extra images and HTML files won’t attract the attention of the site’s legitimate operator.

Or the imposter pages may be part of a short-lived web hosting account – perhaps set up just a day or two before as a “free trial” that will probably be shut down quickly, but not before the crooks will have cut and run anyway.

- Step 3. A web site where the data you put into the login form gets sent.

Sometimes the “drop site” for the stolen data will be uploaded to the same site used in (2); sometimes the crooks use a third site that may be collecting data from several different phishing campaigns at the same time.

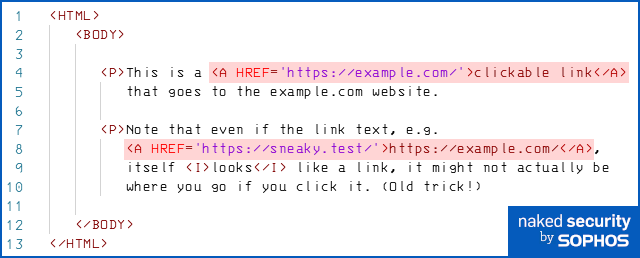

Technically speaking, the clickable link to site (2) appears inside email (1) as what’s known as a hyperlink, encoded into HTML using a so-called anchor tag, written as <A ...>, like this:

The text between the <A> and the </A> usually appears in your browser in blue to denote you can click it to follow a hyperlink jump to somewhere else.

But the clickable text itself isn’t where you go next.

The target of the link, often a URL pointing to another website, is given by the HREF=... value that appears along with the <A>:

(If you want to use the right jargon, you need to known that the <A> part is known as a tag, for which </A> is the matching closing tag. The HREF=... part is referred to as an attribute of the tag.)

Finding the password stealer

Usually, the fake login form that performs the password-stealing part of a phishing scam appears somewhere in the phoney web page on website (2).

So, if you ever need to go looking for the bogus login form, you’ll generally find it on site (2), which, as we just explained, is generally referenced by an HREF=... attribute in email (1).

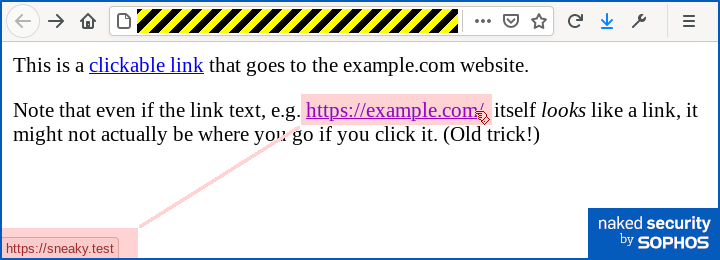

This time, you’re looking for an HTML tag called <FORM>, and instead of using an HREF=... to denote the URL they’re linked to, form tags have an attribute called ACTION=... that tells your browser where to upload the completed form when you finish:

The button that finishes off your data entry and confirms you want to upload the data you just entered is denoted inside the form by an <INPUT> tag with an attribute that says TYPE="submit", as in the example above.

You might expect that hovering your mouse over the submit button in a form would pop up to show you where your data is going next, in the same way that it does when you hover over a hyperlink, but sadly no browser we know of does this:

Cutting out the middleman

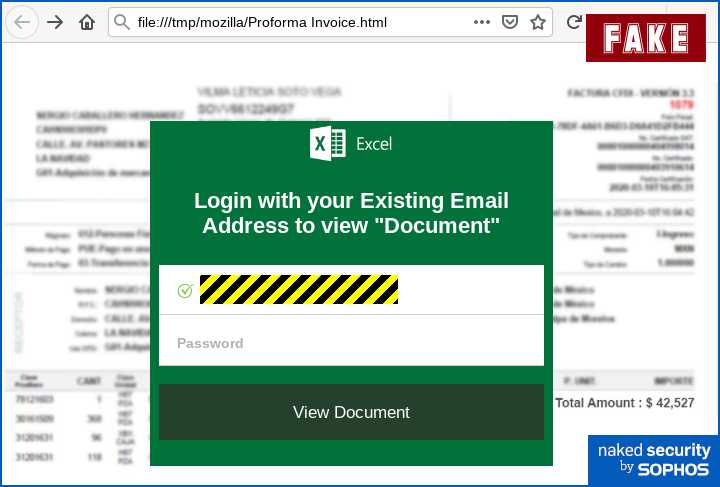

The phishes that we mentioned at the start, one received directly by us and one kindly reported by a reader, worked on the three-step principle we’ve just described.

But there was one important difference.

Step (2), the cloned website with a phoney login page on it, wasn’t reached by clicking a link in the email.

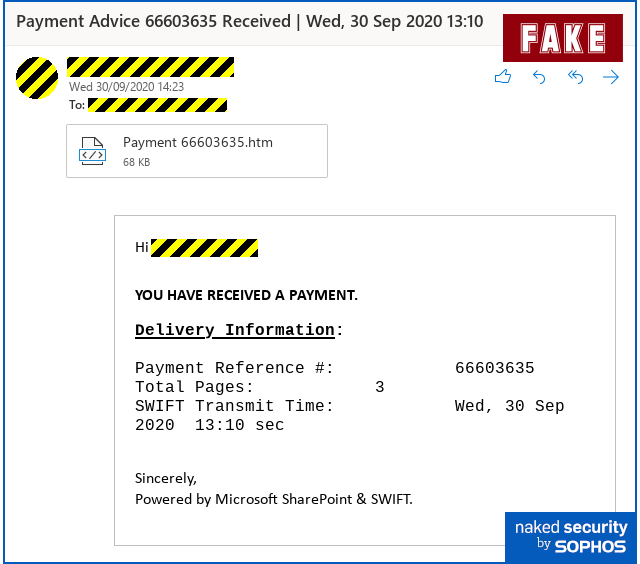

Instead, the bogus web page was brought along for the ride as an HTML attachment, like this:

Opening the attachment doesn’t feel terribly dangerous – after all, it’s not a document that could contain macros and it’s not a PowerShell file or an executable program that could wreak instant havoc.

In theory, opening an HTML attachment should simply open up the enclosed web page in the comparative safety of your browser’s sandbox, as if you had clicked a link.

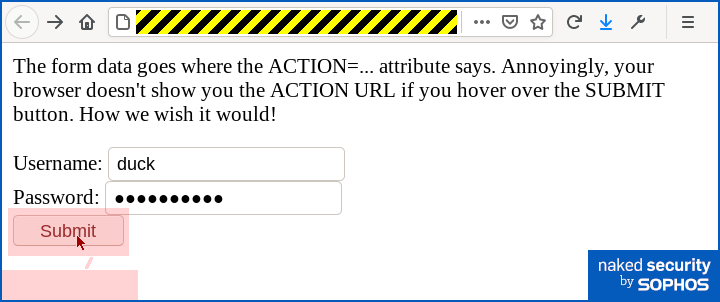

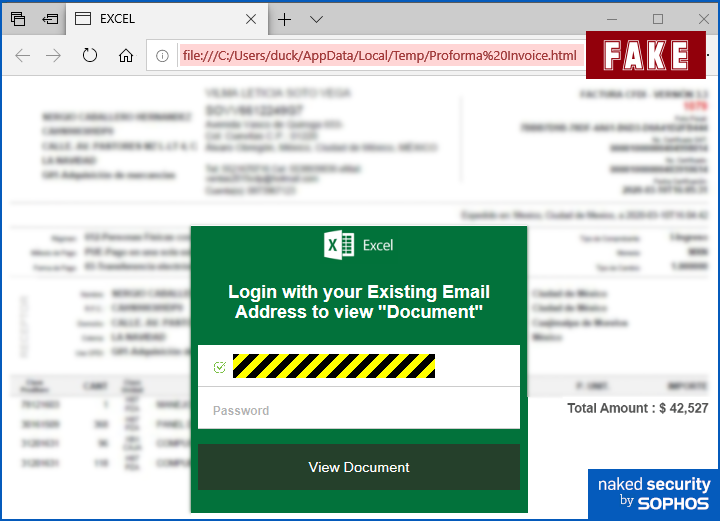

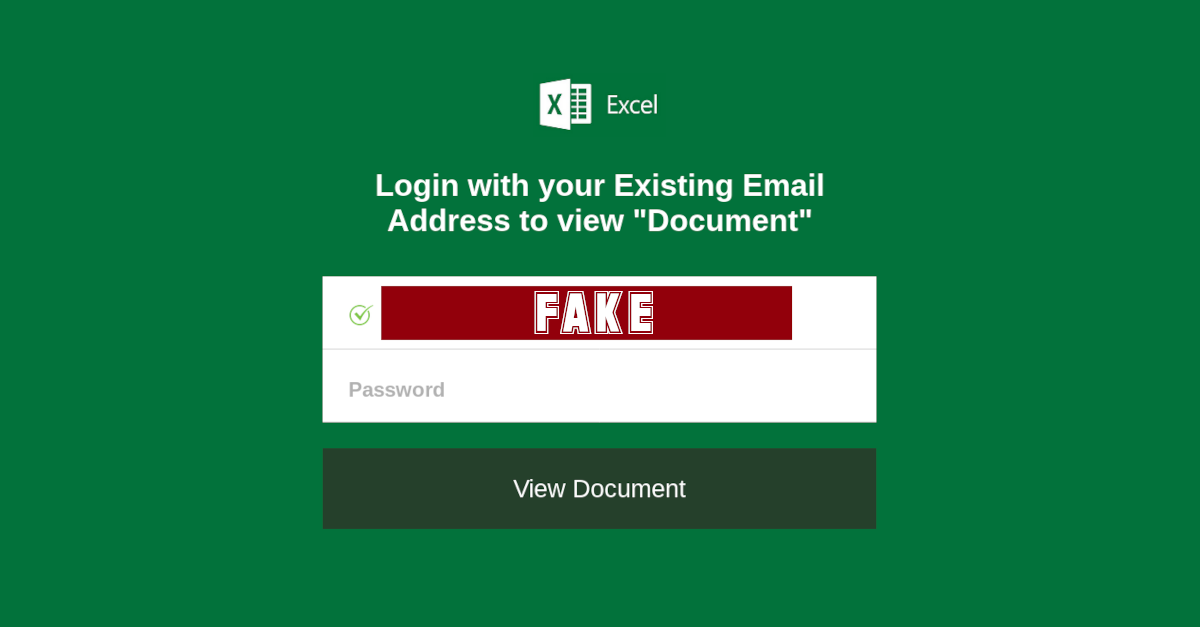

Like this:

When you open an HTML attachment like this, instead of clicking a conventional web link, there are two huge differences:

- There is no link in the email that you could have checked out in advance to look for a fake or suspicious domain name.

- The URL in the address bar is a harmless looking local filename, with no website name or HTTPS certificate you can examine for signs of bogosity.

There are other reasons not to open HTML attachments, notably to do with JavaScript. For safety’s sake, script code inside HTML emails is stripped or blocked when any modern email reader displays the message. That’s a precaution that email software introduced decades ago when self-spreading script viruses such as Kakworm literally spread everywhere. Kakworm’s script code would activate and the virus would spread as soon as the email was displayed, without waiting for you to click any further. When you open an HTML attachment, however, it is no longer under the strict controls of your email client software, and any JavaScript inside the HTML will be allowed to run by default by your browser.

Here’s another example, this time pretending to be a payment processed by SWIFT, a well-known international processing service for financial transactions. (International bank identification codes, now officially BICs are still widely know as SWIFT codes.)

Of course, neither Microsoft nor SWIFT had anything to do with this email, and there isn’t any payment you need to know about.

The message is just a ruse to make you wonder what’s going on here, and opening the attachment brings up a fake login page designed to phish your password:

The innocent address bar

With no clickable link to give the game away, the browser’s address bar is the obvious place where you’d look to try to verify the web page you just landed on.

As you can see above, the website details that show up for HTML attachments opened locally are just local URLs, starting with file:// instead of http:// or https://.

There’s no encryption to look for, and no TLS certificate you can check, because all you’re really doing is browsing a local temporary file.

In our case, they had names that are unexceptionable enough that we didn’t even bother to redact them in the images above:

file:///tmp/mozilla/Proforma Invoice.html file:///tmp/mozilla/Payment 66603635.html

The URLs above are what we saw when we ran our test using a Linux email client and with the Firefox browser, but the results are similar on other platforms.

On Windows, for example, you’ll see something like this:

Tracking the FORM data

As explained above, filling in the forms in the fake HTML pages above will send off your password to websites controlled by the criminals.

Of course, email passwords are amongst the most valuable credentials for crooks to acquire, simply because many people use their email account for password resets on a multitude of other accounts.

So, criminals with control over your email account can probably wrest control of many of your other accounts, too, because any password reset emails will end up where the crooks can access them before you even realise that they’re taking over your digital life.

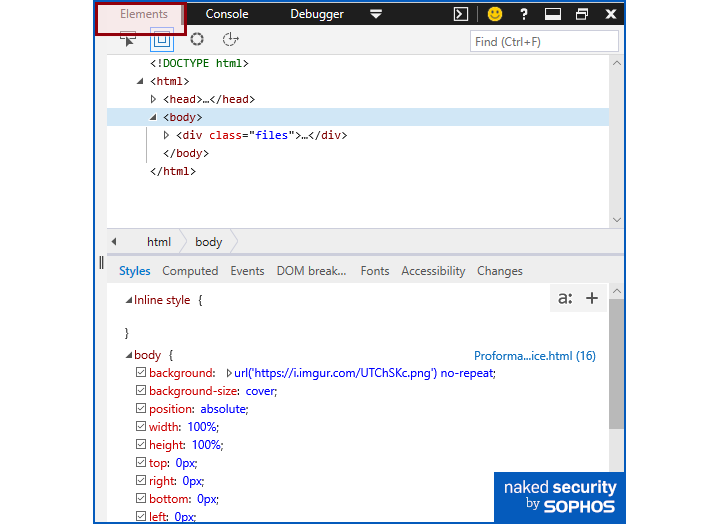

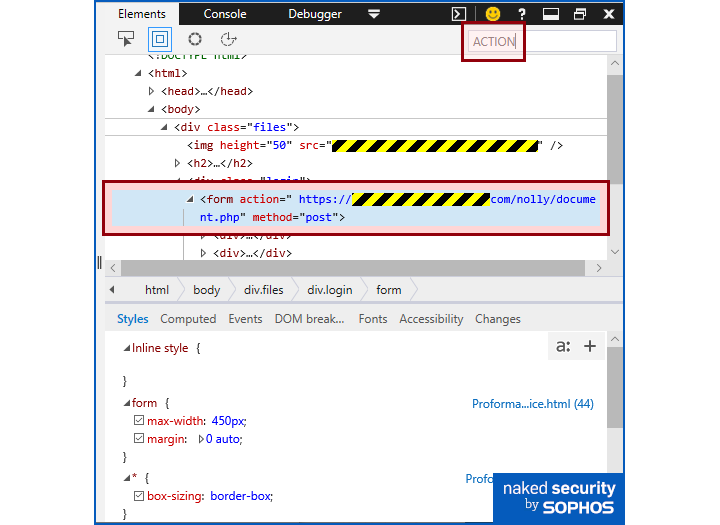

But how to check where a form in a web page will send your data when you submit it?

Unfortunately, we don’t know of any easy way that’s built in to any browser, but you can use your browser’s Developer Tools to do the trick.

In Edge, for example, pressing F12 and choosing the Elements tab will show you a visual view of the HTML structure of the web page:

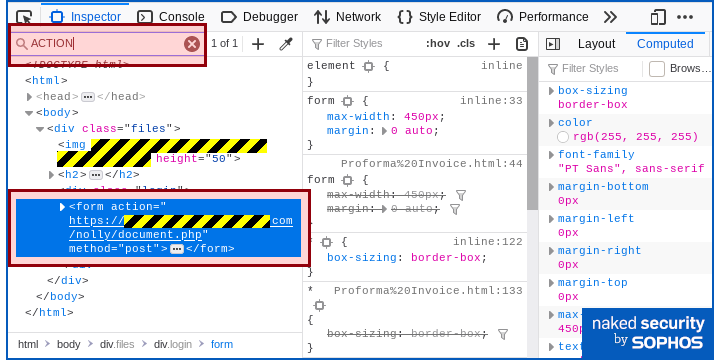

Searching for the text ACTION (the search doesn’t care whether it’s upper or lower case) should reveal any URLs associated with forms on the page, as you see here:

We’ve redacted the URL here, but we will say that it very obviously had nothing to do with any Microsoft product or service, and immediately outed the login form as fraudulent.

In Firefox, the process is similar: Ctrl-Shift-I will bring up Mozilla’s Inspector toolbox.

Choose the Inspector tab and search for ACTION, and you should be able to track down the URLs used for data upload by any of the forms in the page:

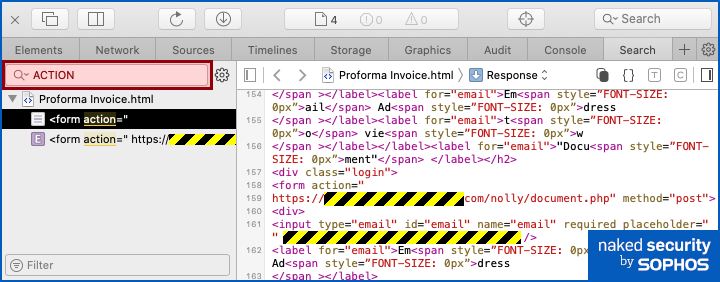

In Safari on a Mac, the key combination to bring up the Inspector is Option-Command-I, after which a search will show you any occurrences of ACTION in the HTML source of the page:

What to do?

The good news is that you don’t need to learn a whole new set of precautions to protect yourself from bring-your-own-webpage phishing scams.

Here’s what to do:

- Avoid HTM or HTML attachments altogether unless they’re from someone you know and you are expecting them. We can’t recall ever receiving an emailed-in web page that wasn’t trying to trick us.

- Avoid logging in on web pages that you arrived at from an email, whether you clicked on a series of links or opened an attachment to get there. If it’s a service you already know how to use – whether it’s your email, your banking site, your blog pages or a social media account – learn how to reach the login page directly. If you always find your own way to your account login pages, you’ll never be tempted by fakes.

- Turn on 2FA if you can. Two-factor authentication means that you need a one-time login code, usually texted to your phone or generated by a special app, that changes every time. 2FA doesn’t guarantee to keep the crooks out, but it makes your password alone much less use to them if they do manage to phish it.

- Change passwords at once if you think you just got phished. The sooner you change your current password after putting it into a site you subsequently suspect, the less time the crooks have to try it out. Similarly, if you get as far as a “pay page” where you enter payment card data and then realise it’s a scam, call your bank’s fraud reporting number at once. (Look on the back of your actual card so you get the right phone number.)

- Use a web filter. A good anti-virus solution (Sophos Home is free for Windows and Mac) won’t just scan incoming content to stop bad stuff such as malware getting in, but will also check outbound web requests to stop good stuff such as passwords getting out. Even in “clickless” attacks like this, the password exfiltration relies on an outgoing web connection that a web filter could block.

Daniel Sprouse

sophos-av is available for linux as well…

Installing it is one of the easiest things to do, as long as you follow simple directions.

Paul Ducklin

I’m afraid I have some bad news.

Sophos Anti-Virus for Linux exists in two forms. There is a a version that you can download as a tarball, forming part of our on-premises endpoint protection product set. You can use these products on their own or with our enterprise console management tool.

And there is a Sophos for Linux version that works with our Sophos Central product, where we provide a management console for you in the cloud so you don’t need your own dedicated servers to do it. However, the various components of the Central product can’t be used standalone.

Sophos Central is now by far the most popular of the two ways to buy and use our product… so much so that from the middle of 2020, we stopped selling the on-premises versions altogether. We’ll update and support them for existing users for another three years, but there are no new licences.

You can guess where this is going.

The free version of Sophos Anti-Virus for Linux was simply a free licence for the endpoint protection version, which doesn’t exist any more. Therefore you can no longer sign up for the free Sophos for Linux either.

Whether or not the new Sophos for Linux will ever be made available in a free/standalone form I don’t know. But I shall pass on your comment – it might influence the product team!

Dave

Well that really is a shame. The moral compass of Sophos seemed to be to protect the little guy with free products, since the little guy likely works for a company and talking favourably is always a good thing for potential sales.

There’s danger of the opposite happening – with AV stripped from the UTM home some time ago, and now the Linux AV not being available either, it’s likely we’ll be talking about competitor products instead.

I used Sophos Linux AV on my Nextcloud VM to prove it wasn’t infected when google blocked my domain as being high risk. I *was* going to transition the family over to Sophos this year, but covid made it difficult so I just renewed Bitdefender for another year instead (I’ll need to do the uninstall and install for the parents-in-law).

+1 for keeping some home protection options for linux available

Paul Ducklin

I don’t accept the implication that we have somehow lost our morality. I think that is an unfair thing to say. (Anyway, persuading people with freebies is marketing, for all that it’s a nice thing to do.)

Our Android product is still free; so is Sophos Home for Mac and Windows, and our Windows Virus Removal Tool, and our XG Firewall. I hope we can find a way to make the new-style Linux product available in a standalone form but that’s not the case yet. (Sophos Central, as the name suggests, is more about managed security than about looking after a whole sea of standalone tools.)

And Naked Security is still here, engaging via written articles, audio and video on cybersecurity issues – all without doing product pitches – to help anyone who wants to hear cybersecurity explained in plain English, for free and with no need to sign up for anything.

I dont think our moral compass has been affected just because SAV for Linux is no longer available as a self-installing tarball :-)

Spryte

Thanks for the tips. Great article.

As one who has written my fair share of HTA utilities in my working life I know the damage a harmfully coded HTML file can create. That is one reason I set my email to receive email as “Text Only” and avoid HTML files like the Plague.

Richard

And bad news for Sophos Home (Free) for Mac – I have had to remove it from my system because it does not “play nice” with Catalina. In particular it was implicated in several WindowServer panics. [A pity, because I used it for several years, with no problems until I updated to Catalina.]

In passing, I note that Sophos Home (Free) uses kernel extensions (kexts) which are deprecated in Catalina and will not work at all in Big Sur.

I now use an antivirus product from another supplier.

Paul Ducklin

I have never had problems with our product on Catalina (I updated the day it came out), so I can’t shed any personal light on this.

The kexts are a bit of a red herring – they will be replaced with system extensions for Big Sur – as you say, that’s not a choice but a necessity.

Bill Scobie

Would using a password manager protect against this? I know LastPass will alert one if credentials are being entered in a site that does not match where LastPass thinks they should be, it seems like that would address the form action problem.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, password managers do indeed provide a handy protection against fake login forms. N either the web page that contains the form nor the web site to which the form points will match anything it knows about…

Cassandra

If advising people to use the Source code reading tools to search for a FORM tag and its associated action, might it be wise to advise to search for ALL FORM Tags as it would be easy enough for phishers to put a “legitimate” CSS hidden FORM tag early in the page before the nasty one?

Paul Ducklin

Yes. You can also use the “inspector” arrow (click on the arrow and then on a specific item on the page) to get whisked to the HTML source (if any) that comprises that component.