Yesterday was Patch Tuesday, and with 123 bugs fixed, including 20 in the “critical” category, we’re saying what we always do, namely, “Patch early, patch often.”

As often happens, however, one BWAIN (that’s shorthand for Bug With An Impressive Name) that was patched in the Windows DNS server is flying high in the headlines because Microsoft itself has come straight out and said:

We consider this to be a wormable vulnerability, meaning that it has the potential to spread via malware between vulnerable computers without user interaction. DNS is a foundational networking component and commonly installed on Domain Controllers, so a compromise could lead to significant service interruptions and the compromise of high level domain accounts.

The vulnerability turned out to be a long-standing bug that needing fixing in every supported version of Windows Server from 2008 to the present day.

The bug has been dramatically dubbed SIGRed, presumably in a cheeky historical nod to the Code Red worm of 2001, but it’s more officially known as CVE-2020-1350, and it has been given a CVSS Base Score of 10.0.

CVSS stands for Common Vulnerability Scoring System, and it’s a cybsecurity bug measurement system promoted by the US government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) that tries to reduce bug severities to a single, dimensionless number between zero and 10.

In truth, this reductionist approach isn’t always helpful – an A-grade washing machine that you use excessively because “the label says it’s green” is much worse for the environment in the long run than an E-grade light bulb you turn on occasionally for the cool effect it produces…

…but in this case, we’re prepared to say that a CVSS score of 10.0, where the absolute maximum is 10.0, is something that really does scream, “Patch now.”

The good news for most of us, at least in terms of patching, is that this vulnerability only affects Windows servers, because the bug is in the Windows DNS server code, not in the Windows DNS client code.

The bad news for many of us, of course, is that this vulnerability affects Windows servers.

If you’re hooked up – whether at the office or from home – to a company network that relies on Windows, crooks who find a way to exploit this bug could directly or indirectly put you at risk, even if you’re not running Windows yourself, by hacking into the core of the network.

The bug and where to find it

As you probably know, DNS is short for Domain Name System, and it’s a distributed, global database that converts human-friendly computer names such as nakedsecurity.sophos.com into network numbers that computers can use, such as 192.0.66.200. (At least, that’s what the name-to-number mapping was for us at 2020-07-15T12:00Z.)

Loosely speaking, there are two broad classes of DNS software: clients that send out requests asking questions such as “where is nakedsecurity to be found?”, and servers that work out the answers to those requests and send back the responses.

Interestingly, the CVE-2020-1350 bug exists in a part of the Windows DNS software that listens for DNS responses coming back, rather than in the part that listens for DNS questions sent out the first place.

In other words, you’re probably thinking that this bug would have to be in the client code, and would therefore affect every Windows computer on the network – after all, DNS servers are there to receive requests, while it’s DNS clients that receive responses.

But DNS servers often need to perform client-like functions, for example by passing on requests that they can’t answer themselves to other servers that can, reading in the replies and reformatting them to reply to the original client request that came in.

So many, if not most, DNS servers – including the Windows DNS server – have code built into them that not only listens for requests but also processes reponses from other servers.

This bug, according to the Check Point researchers who discovered it, is unique to the Windows DNS server software (dns.exe) because the Windows DNS server and client programs don’t seem to share any code.

Having completely different implementations of the make-requests-and-process-replies code in the Windows DNS server program and the Windows DNS client software may sound unusual, but it is not surprising. DNS servers typically need to handle a much broader set of possible DNS requests and replies than pure-play DNS clients, notably for exchanging data with other DNS servers.

How it works

If you’re interested in the innermost technical details of CVE-2020-1350, the researchers who discovered it have dug into it in some detail.

However, unless you already have a basic understanding of the low-level layout of DNS network traffic, as well as some experience in reverse engineering, you might find the deep-dive version rather hard to follow.

So we’ll try to explain what went wrong here, sticking to plain English.

DNS network traffic follows an old and parsimonious format dating back to the early 1980s, revised in the venerable document known as RFC 1035: DOMAIN NAMES – IMPLEMENTATION AND SPECIFICATION from 1987.

Back then, memory space and network bandwidth were in short supply – modems typically ran at 1200bits/sec or 2400bits/sec, and even a fully-loaded IBM PC-XT had at most 640KB of directly usable system memory.

Data wasn’t exchanged in expressive, self-documenting formats such as JSON, as it often is today, but instead packed as tightly as possible into small, dense binary gobbets.

Today, you might encode various on/off settings into a comfortable but bulky JSON representation such as {"compress":true, "retry":true, "log":true, "urgent":false}, but in the 1980s you would pack these settings into a single byte, using one bit each.

The recipient would have to know in advance which byte contained these settings, and which bit position in the byte stood for each of them.

Likewise, today, we might send a chunk of data as a named JSON string, and let the recipient decode it, allocate memory as it goes along, and work out the final size of the data for itself, as in the JSON expression {"data":"ROz\u0002X-TT\u0000\u0000"}.

But in DNS replies, every byte mattered – in fact, DNS was designed with the assumption that almost all common requests and replies would fit into 512 bytes (minus 12 bytes of header data), with a special but slower transmission method defined for longer replies, formatted as two bytes denoting the data length followed by that many bytes of data.

The biggest number you can fit into two bytes, or 16 bits, is 216-1, which is 0xFFFF in hexadecimal or 65,535 in decimal, so DNS replies max out at that size.

There are many sorts of DNS reply, known in the jargon as RRs, short for Resource Records, denoted using 16-bit numbers referred to as TYPEs, each of which is known by a mnemonic name, for example:

Number Known as What it tells you ------- -------- ----------------------------------------------- Type 1 A IP address of this domain name Type 2 NS The official DNS server for this domain Type 15 MX Where to send mail for this domain Type 16 TXT Text strings giving special info (e.g. SPF data)

Most RR types include numerous data fields, packed together in a binary lump as tightly as possible, and one field type that is common across many RRs is known as a NAME, a text string that is encoded as a single byte denoting its length (thus maxing out at 0xFF or 255 bytes), followed by the NAME data.

You can probably guess where this is going by now.

What happened?

When DNS was extended in the 1990s to support digital signatures in order to make it hard for crooks to inject fraudulent requests and replies into the heart of the sytem, a new RR type with the number 24 and the mnemonic code SIG (short for signature) was defined.

That record type didn’t last long, soon being superseded by record type 40, known as RRSIG (the RR- prefix is tautological, givem that it is an RR by definition, but the text string SIG had obviously already been used).

RRSIG records have the same format as SIG records, but are subject to different rules about how the data in them gets formatted.

At this point, we can only guess at what happened – but we suspect that someone at Microsoft copied some or all of the code that was used to process SIG replies, used it to help build the code that would handle the new-fangled RRSIG replies, made numerous changes, bug fixes, improvmements and extensions, as programmers do with good reason…

…while the original code to handle SIG replies sat there unloved, untouched and, in fairness, almost totally unusued, given that SIG records probably never turned up in real-world traffic any more.

Integer overflow – from years ago

Anyway, as the Check Point researchers discovered while on a spelunking expedition, the code that handles SIG records seemed to make the following assumptions:

- The largest amount of data that can possibly appear in a DNS reply is 65,535 bytes.

- Therefore the maximum amount of memory that will be needed to store that data when it’s unravelled is 65,535 bytes.

- Therefore an

unsigned short int(a 16-bit number) gives enough numeric precision for the length calculations.

Unfortunately, SIG records include a NAME field that can be transmitted in compressed form, using DNS’s rudimentary compression algorithm, so that a NAME string that ultimately requires as much as 255 bytes of storage when extracted may take up as little as two bytes in the DNS reply itself.

SIG records also include a field for the digital signature data itself, which can be of arbitrary length, so it’s easy to construct a booby-trapped reply such that the total amount of data sent in the actual reply is right on the 65,535 byte limit.

But the code used a 16-bit integer value when calculating how much memory it would need after decompression – so if you imagine the code being confronted with 65,535 bytes of raw data in the response plus (say) another 40 bytes extra denoted by an attacker using a cunningly-crafted compressed NAME field…

…it would compute the sum as 65,535+40 but wrap around back to 39, in the same way that when you wind an analog clock forward 3 hours from 11 o’clock, you wrap around at 12 and end up with 11+3 = 2 o’clock, not at 11+3 = 14 o’clock as you might expect on a digital timepiece or a railway timetable.

The DNS server would then incorrectly allocate just 39 bytes of memory for its SIG record, but immediately try to shovel 65,535+40 bytes into the hopelessly undersized memory buffer, thus crashing the DNS server.

Only one bug?

Other parts of the Windows DNS server code process similar types of RR data, and you might therefore expect this bug to be repeated elsewhere in the code, notably in the section where newer-style RRSIG records are handled.

But even though the researchers went looking to see if they could find other instances of this problem, or something like it, they came up empty.

Indeed, they reported that some similar parts of the code explicitly checked for an integer overflow, so we’re therefore willing to guess that the bug survived in the SIG reply handler simply because of code rot.

We suspect that because SIG records never showed up in real-life DNS traffic, the bug was never triggered, so the incorrect code attracted neither interest nor suspicion, languishing there unseen and unpatched.

Until now.

Interestingly, one reason why the RRSIG code might not have inherited this bug, even if it started off as a copy-and-paste of the SIG handler, is that the specification for RRSIG resource records explicitly states that compression of the NAME field is not permitted.

Even if the RRSIG code started life with a possible integer overflow that no one noticed, modifying the code to enforce the new “no compression allowed” rule would have sidestepped the bug anyway by making it impossible to create the condition needed to trigger it.

Is it exploitable?

So far as know, no one has yet figured out how to exploit this bug beyond merely crashing the Windows DNS server.

Check Point admitted that it wasn’t able to get further than that, saying:

Due to time constraints, we did not continue to pursue the exploitation of the bug […], but we do believe that a determined attacker will be able to exploit it. Successful exploitation of this vulnerability would have a severe impact, as you can often find unpatched Windows Domain environments, especially Domain Controllers. In addition, some Internet Service Providers (ISPs) may even have set up their public DNS servers as WinDNS.

In Microsoft’s words:

An attacker who successfully exploited the vulnerability could run arbitrary code in the context of the Local System Account. Windows servers that are configured as DNS servers are at risk from this vulnerability.

So, given that Microsoft is calling this a “wormable vulnerablity”, we reiterate our earlier warning to patch now.

Just in case…

If you can’t or don’t want to apply the patch just yet, Microsoft has come up with a workaround to suppress the bug:

In the registry, locate the key:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\DNS\Parameters

Find (or create if not present) the DWORD value called:

TcpReceivePacketSize

Set the value data to:

FF00 (hexadecimal) or 65280 (decimal)

Then restart the DNS server.

We’re assuming this workaround protects you because 65,535-65,280 = 255, and 255 is the maximum length that a NAME field in a SIG record is supposed to have, even after decompression.

So if the DNS server rejects all incoming replies bigger than 65,280 bytes, the integer wrap-around condition will never be reached – there will is always enough space for any compressed NAME data to grow up 255 bytes longer, thus preventing the crash even in the face of a booby-trapped reply.

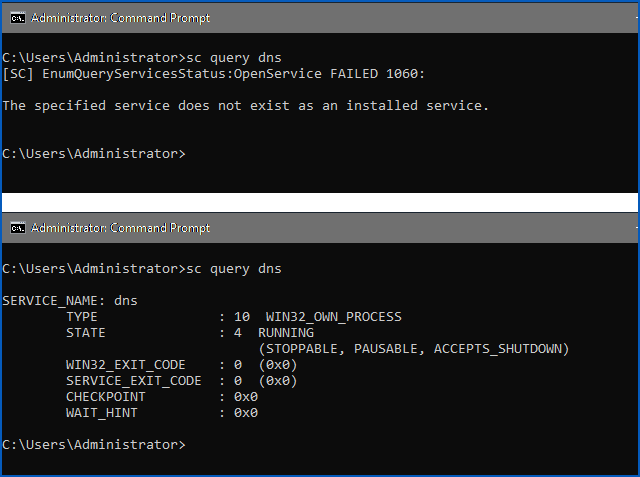

If you’re not sure whether Windows DNS Server is running or not on a computer you look after, you can use the command sc query dns at an Administrator command prompt to find out:

sc query if DNS Server is not installed.

Below. Output of sc query if DNS Server is running.

SusanTechy

You “accidentally” forgot to tell anyone WHICH version of Windows Server has this problem.

Gee, thanks!

Paul Ducklin

I did link twice to Microsoft’s own CVE-2020-1350 page in the article, and I assumed that the fact that this bug has been around for years implied that this affects “Windows Server” in the widest possible sense of that phrase, but I shall add a note to the article to make it clear to click on the Microsoft links to see the official list.

FWIW, the bug exists in pretty much every supported Windows server version that there is, including Server Core installs. So we’re talking about 2008, 2008R2, 2012, 2012R2, 2016, 2019 and all the recent versions with the new “Version XXXX” numbers in YYMM format that are annoyingly confusig because YYYYMM or YYYY.MM would have been way clearer, viz. Version 1903, Version 1909 and Version 2004.

HtH.

Steve

Great article (as usual), very well written. Thanks!

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words – appreciate the feedack!

Ron

Thanks for the great read and content. Always a great source of information!

richard

Thanks Paul for such a great article. So Microsoft don’t have a patch yet? You need to implment a workaround? (July 2020).

Paul Ducklin

No, as the article says, the workaround is only there in case you are the sort of company that uses what are called “change windows” – where you only ever make changes such as patches and reboots only on certain days, e.g. Saturdays, or not at certain times, e.g. in the month that is at the end of the financial year. I have reworded the last section to make it more obvious that the workaround is not the only solution available.

(The headline “Patch now!” is a bit of a giveaway that there is a patch out :-)

Paul Nurse

all you need to pull this off is some JavaScript on a webpage, crazy. I’ve got my updates out the way!

Chad Kelley

As I read your article I was trying to determine if public facing Microsoft DNS servers are mainly at risk? Or if even those DNS servers that sit behind firewalls & are used strictly for internal Active Directory name resolution can have the SIG bug exploited using crafted web pages when a Microsoft client PC browses the Internet & the internal DNS servers listen to forward requests out? Initially I was under the impression the answer was “no”, but not sure after reading that?

Paul Ducklin

The server gets attacked by receiving a DNS reply that is booby-trapped, so that can in theory happen to a server on your LAN (rather than outside or in the DMZ) if it’s allowed to make requests of its own to external DNS servers rather than going through an intermediate DNS server at your own network edge. In other words, if someone on your LAN can get an unpatched Windows DNS server to look up a domain of their choice, and they control the authoritative name server for that domain, they could stuff a redundant but booby-trapped SIG record into the reply and the poisoned DNS reply packet would be consumed by your server.

If the Windows DNS server itself always uses an upstream server to its external lookups – a DNS server on your firewall, for example, that does some sort of DNS-based filtering – and the firewall DNS server doesn’t blindly proxy the entire DNS reply back, you ought to be OK, assuming that the firewall is Linux or Unix based and therefore itself not vulnerable

Chad Kelley

Thanks Paul for the clarification.

Josh

thanks for the content. as a follow up – how can you tell if your DNS server’s been compromised? if compromised, is there a known fix? or will the registry patch fix it?

Paul Ducklin

That’s a very broad question: “How do you know if your server’s been compromised?” If you are worried abuse about this particular bug, I think the risk is very small because – as far as we know – it was responsibly disclosed, the patch is out, and we have seen no signs of any crooks having yet worked backwards from the patch and the Check Point article to a working exploit. As for “how you you tell if a computer already has malware on it”, a good place to start is to scan it with a bang-up-to-date malware scanner; also, check your network, domain and syste, logs for unusual activity such as the creation of new accounts, the installation of unexpected software, the use of unusual or unexpected sysadmin tools, and so forth. (There’s a link to our various free scanning tools at the bottom of the article. But bear in mind that fully scanning all files on a large server may take a while!)

The registry modification described above won’t uncompromise a server that has already been hacked (by this or any other trick), and it’s important not to think of the registry change as “a patch” – it’s a temporary workaround until you can get the patch installed…

Josh

I misspoke regarding the workaround/modification – calling it a patch. thanks for the correction. The reason i ask is that our DNS was not working this morning for about 4 hours. We have a 2012R2 host server, hosting 2 VM servers. though we’re now back up running, i couldn’t ignore the coincidence. I could remote into the office, but users couldn’t resolve dns going out. Again, it seems resolved, but with this new exploit, I haven’t been able to find info yet on how to determine if we were affected – many intrusions are “findable” if you know what to look for (registry changes, changes to hosts file, etc) – thanks again

Dee

The registry value should be 0xFF00 not FF00. Great article though.

Paul Ducklin

Actually, you select the base you want to use with the radio button in the Regedit dialog box shown in the screenshot. I chose (*) Decimal in that image and typed in 65280, but if you choose (*) Hexadecimal then you just type in FF00. The dialog already knows to expect a value in hex, so the “0x” at the start is not only redundant but also impossible to type in – the dialog box only accepts the keystrokes 0-9 in Decimal mode and 0-9A-Fa-f in Hexadecimal mode, so pressing x does nothing.

Once you have typed in FF00 then the data will display in the GUI as “0x0000ff00 (65280)”, but you really do enter it without the “x”. (Truly – I just fired up my VM and checked it again to make double-sure :-)

Thanks for the fedeback, BTW, it’s much appreciated.

barack

hey Paul, what if the server is not running windows DNS Server service? does this vulnerability affect it in any way?

Paul Ducklin

This vulnerability depends on the Windows DNS Server running and listening on TCP port 53 (the bug can’t be triggered by UDP-based DNS traffic).

If DNS Sever isn’t installed, you aren’t at risk and there is nothing to patch. If it is installed but the service is not running, you aren’t at risk but you should make sure you have the patch anyway…

…just in case someone turns it on in the future.

barack

thank you , you and this article are the best on the net, and i read them all really (2 pages of google) most are just copy paste, other just click baits.

Keep it up, rare to find a real author that really knows what he s writing about nowadays.

Paul Ducklin

Thanks, I appreciate your kind words!

Brian Hampson

Just a quick note – the 2008R2 patch doesn’t apply successfully (at least for non-ESU people) so most of us that are running 2008R2 servers are S.O.L. on the patch. Regedit, it is…. :(

https://www.reddit.com/r/sysadmin/comments/hru0ra/anyone_having_issue_installing_the_patch_for_the/

Paul Ducklin

AFAIK, support and updates for Windows Server 2008R2 ended more than six months ago. As you say, if you don’t have an exended support licence then there isn’t an update for you (indeed, you probably haven’t had any other updates either, from February 2020 Patch Tuesday onwards).

I guess you will have to: [a] pay for extended support, [b] upgrade to a newer version of Windows Server, [c] switch away from Windows (there are several free options available), or [d] use the Regedit workaround and leave it in place permanently.

Brian Hampson

Well, this critical flaw has been around for 17 years and as they put it, IS HIGHLY WORMABLE. It’s not like they didn’t set a precedent by putting out a patch for Eternal_Blue for XP after _IT_ was dropped from support…

Paul Ducklin

To be fair, Microsoft didn’t shout that it was HIGHLY WORMABLE – they said, a bit more calmly, that they considered it a wormable vulnerability. (ETERNALBLUE was already exploitable; the exploit code was known to be in circulation; and the exploit could be applied against pretty much and Windows computer, not only against Windows servers running DNS.) Given that this [a] is not yet a hackable hole [b] is only to be found on a subset of Windows server, already a small subset of all Windows computers out there [c] can be remediated by an easily-applied workarond supplied by Microsoft…

…well, I get your point, but suggesting that Microsoft is duty bound to patch out-of-support systems for free just because it has done so once or twice before in tricky cases is IMO bit unfair.

A Admin

Thanx Paul, great Article.

Short Question: If my Windows servers use a Sophos UTM 9.x as a DNS forwarder, will they protect me because they are running on linux, or will the ips protection find the possible DNS Attack ?

Best regards!

Paul Ducklin

You will need to confirm with Support, but I think that, if your Windows servers are set up so they only ever make outgoing DNS requests to the UTM, and receive replies from the UTM, then the UTM’s replies – which are replies to replies – should be safe, while any booby-trapped replies sent to the UTM will fail because it’s not running Windows DNS Server.

We also have some IPS rules that can spot booby-trapped replies anyway (see the SophosLabs article for details), so I would like to think that the UTM would simply eat a dodgy DNS packet and not consider it any further…