If you’re a Naked Security Podcast listener, you’ll have heard Sophos’s own Peter Mackenzie telling some fairly wild ransomware stories.

Peter works in the Managed Threat Response (MTR) part of our business – in his own words, if your network’s on fire, he’s one of the people who will rush in to try to fix it.

As you can imagine, plenty of his deployments come in the aftermath of ransomware attacks.

A few years ago ransomware criminals typically used what’s called the “spray-and-pray” approach – or what might more appropriately be called “spray-and-prey”, given the entirely predatory nature of these attacks.

A ransomware gang might have emailed a malicious attachment to ten million people, relying on ten thousand of them opening it up and getting scrambled, and then banking (figuratively and literally) on three thousand or so of the victims being stuck with little alternative but to pay up $350 each, for a total criminal pay-check of $1,000,000.

Make no mistake, those early ransomware criminals, such as the crooks behind malware such as CryptoLocker, Locky and Teslacrypt, extorted millions of dollars, and their crimes were no less odious or destructive overall than what we see today.

But today’s ransomware criminals tend to pick entire organisations as victims.

The crooks break into networks one-at-a-time, learn the structure of the network, work out the most effective attack techique for each one, and then scramble hundreds or thousands of computers across an entire organisation in one go.

In cases like this, where an entire business may find its business operations frozen because all its computers are out of action at the same time, ransom demands aren’t just $300 or even $30,000 – they may be $3,000,000, or even more.

As you can imagine, this means that the ransomare part of today’s file scrambling attacks – the malware program at the heart of the scrambling process – is now just one piece in a much bigger toolbox of tricks that a typical ransomware gang will have up their sleeves.

Last week, for example, we wrote about an attack by the Ragnar Locker crew in which they wrapped a 49KB ransomware executable – a file created specifically for one victim, with the ransom note hard-coded into the program itself – inside a Windows virtual machine that served as a sort of run-time cocoon for the malware.

The crooks deployed a pirated copy of the Virtual Box virtual machine (VM) software to every computer on the victim’s network, plus a VM file containing a pirated copy of Windows XP, just to have a “walled garden” for their ransomware to sit inside while it did its cryptographic scrambling.

But that’s far from everything that today’s crooks bring along for a typical attack, as SophosLabs was able to document recently when it stumbled upon a cache of tools belonging to a ransomware gang known as Netwalker.

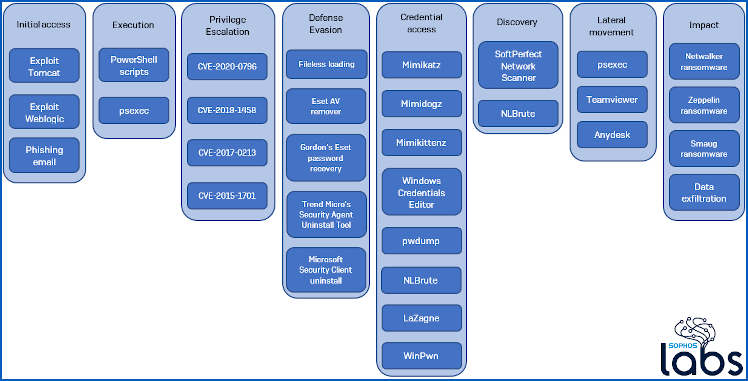

The columns are laid out to fit the MITRE ATT&CK matrix.

Above, taken from the SophosLabs report, is a chart showing the range of tools used by these crooks during a typical attack.

From left to right, the columns reveal the various activities that the crooks work on as the attack unfolds:

- Initial process. The crooks need to get a foothold into the network first, and this gang likes to use a combination of phishing emails and unpatched vulnerabilities. Note that the phishing emails in an attack of this sort almost never contain the ransomware itself – that part of the attack is revealed for the first time much later on, when the crooks have the final onslaught planned out.

- Execution. Ransomware crooks typically use popular, legitimate tools – the sort that many sysadmins themselves use all the time, and may be used to seeing in their system logs – to distribute and execute their malware.

- Privilege escalation. If the crooks can acquire administrative powers without cracking or stealing any sysadmins’ passwords, they will. Here you see the favourite exploits of this crew. Even though patches have been out for these holes for anywhere from two months to five years, the crooks don’t have a lot to lose by trying freely available exploits that are known to work on unpatched computers, before moving on to more complex attacks.

- Defence evasion. Once the crooks have given themselves equivalent power to an official sysadmin, they can start to “adjust” the security posture of the network as a whole. Sometimes they will do this using the official tools for the job, but they also typically keep a stash of unofficial “tweaking tools” that can uninstall or turn off security software to make later parts of the attack easier and less likely to trigger alarms.

- Credential access. Many popular and freely available open source tools exist to snoop around in memory in the hope of finding passwords or authentication tokens that give crooks ever-more privileged access to the system. These tools are popular with penetration testers – indeed, some of them are pitched as security tools, though they’re essentially malware when run by anyone unofficial.

- Discovery. Crooks love a network map as much as your own IT department, and typically use a variety of tools to find out not only how many endpoints and servers an organisation has, but also to learn which services are hosted on what servers (even if they’re in the cloud). In modern malware attacks, crooks go out of their way to find any online backup servers you have. They then make every effort to wipe out your backups first to make it more likely that you will be forced to pay up. Ransomware attackers also often take the trouble to identify servers that host company-critical databases. If they can shut down your database applications just before they launch their encryption attack, then the database files will not be locked and their ransomware will scramble them along with everything ele.

- Lateral movement. Attackers love RDP (remote desktop protocol), which is built into to Windows, and will abuse it wherever it’s left open, accessible and insecure. (The tool called NLBrute you see in the Discovery column is an automated password guesser for RDP.) But where RDP is not available, the crooks will often bring along popular and legitimate remote-control tools – perhaps even ones you already use in your network and thus that will not look out of place – to help them “administer” your network with ease.

- Impact. Notice that only three of the boxes in this whole chart are actually ransomware programs. All the other boxes amount to what you might call the supporting cast or the construction tools for the final attack.

Data exfiltration

Perhaps the most important thing to take from this whole chart is the bottom-most box at the far right, labelled Data exfiltration.

When ransomware first became a serious problem about seven years ago, the idea of scrambling your files in place was a way for the crooks to “steal” your files – in the criminal sense of permanently depriving you of them – without having to upload them all first.

The average computer and the typical network just didn’t have the bandwidth to make that possible, and the average crook didn’t have enough storage to keep hold of it all.

But cloud storage has changed all that, and ransomware crooks are now commonly stealing some or all of your data first, before unleashing their ransomware.

They’re then using this stolen data to increase the pressure of their blackmail demands by threatening to leak or sell your data if you don’t pay up, thus giving them criminal leverage even if you have a reliable and efficient backup process for recovering your files.

What to do?

Here, we’re going to refer you to our April 2020 article entitled 5 common mistakes that lead to ransomware.

In quick form, our five tips are:

- Protect your system portals. Don’t leave RDP and other tools open where they aren’t supposed to be. The crooks will find your unprotected access points.

- Pick proper passwords. Don’t make it easy for crooks and their password guessing tools. Use 2FA wherever you can.

- Peruse your system logs. As the chart above shows, the crooks often use a lot of sysadmin tools that would probably show up as unusual in your logs if you were to look.

- Pay attention to warnings. Exploits that ran but failed could be reconnaissance for a future attack rather than an attack in their own right. (See 3.)

- Patch early, patch often. The Netwalker crooks wouldn’t bother with a CVE-2015-1701 exploit from five years ago if it never worked. Don’t be the network where it does!

Of course, don’t forget the obvious – make sure you are using anti-ransomware protection. Sophos Intercept X and XG Firewall are designed to work hand in hand to combat ransomware and its effects. Individuals can protect themselves with Sophos Home.

Latest Naked Security podcast

LISTEN NOW

Click-and-drag on the soundwaves below to skip to any point in the podcast. You can also listen directly on Soundcloud.

Wilderness

Excellent article. You might elaborate upon the several ways in which Sophos Central and other Sophos products would catch such an attack.

Richard Smith

“Pirated VirtualBox” – VirtualBox is free, bit hard to pirate something you can freely download :)

Paul Ducklin

If you download it to use in violation of the licence then you are, in my book, most certainly pirating it. (IIRC, Virtual Box is free to use, but you are not entitled to redistribute it as these crooks did.)

The fact that something is “free” does not inevitably make it “free for all”. I chose the word “pirated” on purpose and I am sticking with it.

Wilderness

Both of you are right: the common usage of ‘pirated’ indicates the theft of non-free software, AND they were using the free product in a way that breaks their terms of service. Can I think of a better word?

Not really.