When cybercrooks first got into phishing in a big way, they went straight to where they figured the money was: your bank account.

A few years ago, we used to see a daily slew of bogus emails warning us of banking problems at financial institutions we’d never even heard of, let alone done business with, so the bulk of phishing attacks stood out from a mile away.

Back then, phishing was a real nuisance, but even a little bit of caution went an enormously long way.

That’s the era that gave rise to the advice to look for bad spelling, poor grammar, incorrect wording and weird-looking web sites.

Make no mistake, that advice is still valid. The crooks still frequently make mistakes that give them away, so make sure you take advantage of their blunders to catch them out. It’s bad enough to get phished at all, but to realise afterwards that you failed to notice that you’d “logged into” the Firrst Bank of Texass or the Royall Candanian Biulding Sociteye by mistake – well, that would just add insult to injury.

These days, you’re almost certainly still seeing phishing attacks that are after your banking passwords, but we’re ready to wager that you get just as many, and probably more, phoney emails that are after passwords for other types of account.

Email accounts are super-useful to crooks these days, for the rather obvious reason that your email address is the place that many of your other online services use for their “account recovery” functions.

A crook who can get at your emails before you do can use the [Reset password] button on your online accounts and click on the “choose new password” links that come back via email…

…without you ever noticing that a password reset was requested.

Social media passwords are also valuable to crooks, because the innards of your social media accounts typically give away much more about you than the crooks could find out with regular searches.

Worse still, a crook who’s inside your social media account can use it to trick your friends and family, too, so you’re not just putting yourelf at risk by losing control of the account.

Indeed, we now see more phishing attacks that are going after email and social media passwords than we do attacks against online banking accounts.

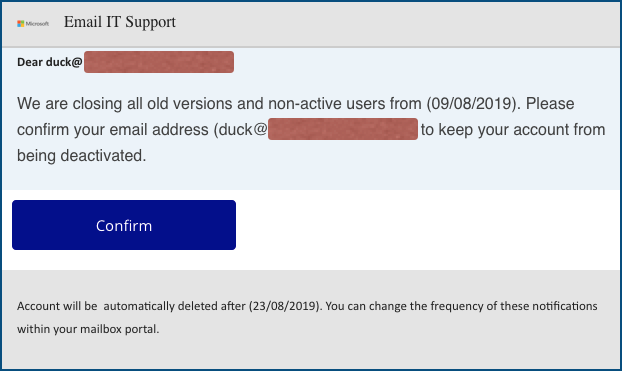

Here’s a not-so-good one from this week that was after webmail passwords:

This message did indeed mention an account that’s not used much any more, so the crooks got lucky with the timing of the message.

But the ripped-off Microsoft logo is messed up and the text “we are closing all old versions” doesn’t really make sense, so your bogosity detectors should be going off by now.

The [Confirm] button is a bit sneaky – the crooks obviously wanted to avoid saying anything about “logging on” in their email, because many recipients these days know that’s a red flag.

Emails with login links are almost always bogus, especially for mainstream webmail accounts, and years of publicity about the risks of clicking through when emails demand you to “login now” have made us nervous of the L-word.

(It’s easy enough to memorise your webmail site name – for Microsoft mail, outlook.com will do the trick; for Google you just put in gmail.com; and so on.)

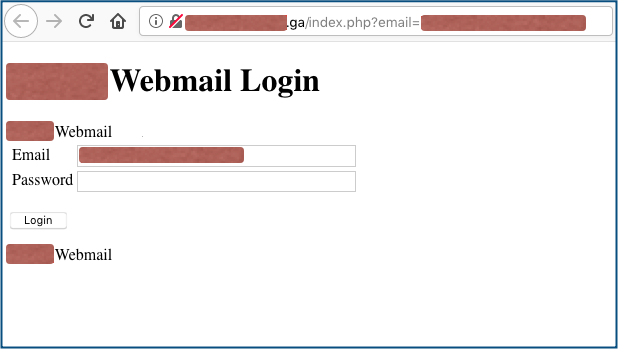

Of course, the [Confirm] button doesn’t do quite what it says, because you do end up at a login page anyway, and that’s where this phish shows its carelessness:

There’s no HTTPS (note the missing padlock); the domain name looks (and is) bogus; the login page doesn’t look like any webmail service I’ve ever used; and the whole thing is clearly fake.

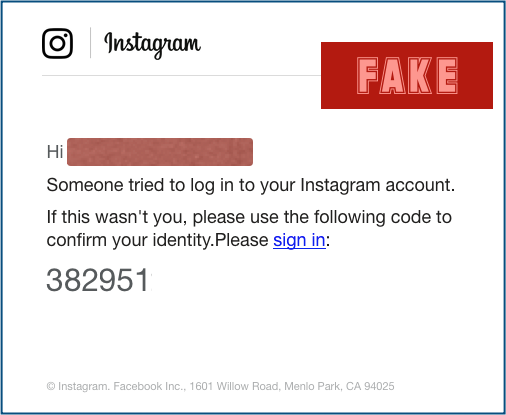

But here’s another attack we received this week that was much more believable, this time going for Instagram accounts:

We dont like to admit it, but the crooks thought this one through.

Apart from a few punctuation errors and the missing space before the word ‘Please’, this message is clean, clear and low-key enough not to raise instant alarm bells.

The use of what looks like a 2FA code is a neat touch: the implication is that you aren’t going to need to use a password, but instead simply to confirm that the email reached you.

And two-factor authentication codes kind of ooze cybersecurity – because, well, because 2FA.

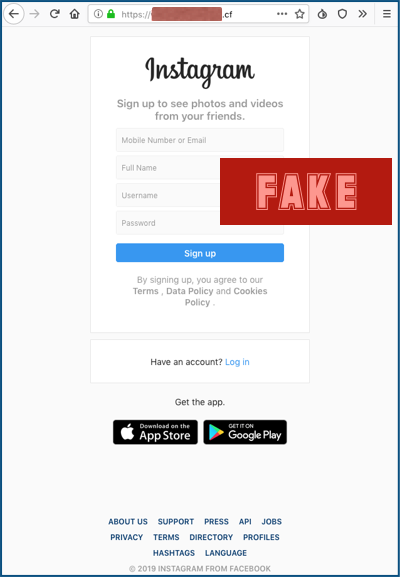

If you click through, you ought to spot the phishiness from the domain name alone – we’ve redacted the exact text here, but it’s a .CF (Centrafrique) domain that nearly spells “login”, but doesn’t quite:

If we had to guess, we’d suggest that the crooks didn’t get quite as believable a name as they wanted because they went for a free domain name. (CF is one of many developing economies that gives away some domains for nothing in the hope of attracting users and selling well-known words and what it thinks are cool-sounding domain names for $500 or more.)

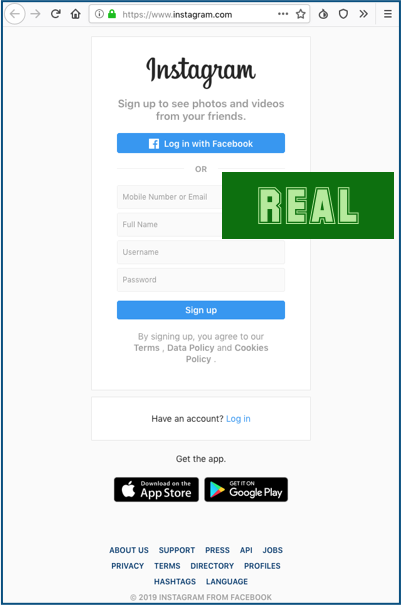

Nevertheless, the phishing page itself is a perfectly believable facsimile of the real thing, and comes complete with a valid HTTPS certificate.

Remember that web certificates keep your connection to the site secure and stop the replies being snooped on or tampered with, and they vouch for the fact that the person who acquired the certificate really was able to login to the website and modify it.

But they don’t vouch for the actual content of the web pages, or for the files that are stored on the site and served up by it.

In other words, a site without a padlock definitely isn’t to be trusted, in the same way that typos and grammatical errors should turn you away; but a site can’t automatically be trusted just because it has a padlock and was advertised with emails that were spelled correctly.

The real Instagram login page is pretty close, so you can’t rely on visual mistakes in the password screen itself:

What to do?

The phishing page looks OK, and it has an HTTPS padlock just as you’d expect, so how are you supposed to spot phishes of this sort?

The good news is that, despite our grudging admission above that the crooks had come up with a phish that’s well above average in believability, there are nevertheless some telltale signs that give it away.

Watch out for any and all of these tricks whenever you receive an email that claims to be a security warning.

- Sign-in link in email. Easy solution: never use them! If you need to sign in to Instagram, you don’t need a link to find it. Use the app on your phone or a bookmark you set up yourself from your browser. Yes, it’s slightly more work. No, it’s not difficult.

- Unexpected domain name. Make sure you know where your browser has taken you. If the address bar is too short to see the full URL, copy and paste the text out of it to make sure. If it looks wrong, assume it is wrong and ignore it, or take a second opinion from someone you trust. Yes, it’s slightly more work. No, it’s not difficult.

- Unreasonable request. If you are worried that someone else has been logging into your account, use that account’s official way of checking your login activity. Don’t rely on web links that could have come from anywhere. Annoyingly, each social media app does this a bit differently, but once you know where to look you’ll never be tricked by an email like this again. Yes, it’s slightly more work. No, it’s not difficult.

To view your login activity on Instagram. Go to your Profile page, tap the hamburger menu (three-line icon) in the top right, then the Settings option at the bottom of the screen. From there, go to Security > and then Login activity >

LEARN MORE ABOUT HOW TO STOP PHISHING

Other ways to listen: download MP3, play directly on Soundcloud, or get it from Apple Podcasts.)

Alan Parker

Typo in your text explaining why the message does not scan properly. You’ve used

we are closing all old verions

instead of versions.

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks. (Irony not lost on me :-)

J G

Your advice to “look for bad spelling, poor grammar, incorrect wording” will not distinguish the average Nigerian from the average U. S. college graduate.

Paul Ducklin

Not sure quite what that tells us about phishing, but I approved the comment anyway.

My experience with phishing emails is that they show, on average, poorer attention to spelling and grammar than legitimate emails, even though some phishes are as well-written as the best professional emails (indeed, many are copied and pasted, so that is almost a truism) and some professional emails are worse than the average phish.

I find that I can rarely be sure of the ethnicity, nationality or educational level of the person who wrote the phish; even if I could I am not terribly sure how I could use that information to reach any purposeful conclusion; and so I am not really sure why I should care.

Nobody_Holme

This is the first one of these in years I’ve not facepalmed at because of how obvious it was.

Mildly impressed.

anonymous coward

I can’t take any article seriously in which a new paragraph is started for nearly every new sentence.

Paul Ducklin

*All* my paragraphs, for what that word is worth, are single sentences. (I exclude parenthetical remarks, sidebars and bulleted lists.)

I have written all my articles in this style for many years for two main reasons: I prefer the way it looks, especially in a mobile browser; and people who aren’t native speakers of English tell me it makes the material easier to follow.

I am simply not convinced that having vertical whitespace between every sentence makes an article less legible, but I do think it makes the article more readable to many people.

It certainly doesn’t alter the correctness or the value of the content.

And that is why I do it.

anonymous coward

I appreciate the serious reply to a silly comment. The other one, too. :)

anonymous coward

And you misspelled “did’t” in an article pointing out hacker flaws. Ironic.

Paul Ducklin

Fixed, thanks.

(Strictly speaking, the article isn’t about hacker flaws but about believability, and the article isn’t an email asking you to click a link – so the irony is modest at best.)

Mr.Greenjeans

Well, another red flag I see is that if I were tempted by an unsolicited E-mail to log in to confirm my identity, their ‘Sign Up’ page is asking for way too much information if I already have an account. That would also point me back to inspecting the URL, because they did not send me to the Log-In page directly. I would assume that inspecting both links on the fake site would show me identical bogus URLs.

Paul Ducklin

Make sure you inspect that URL anyway!

In this case, the bogus login page actually offers less than the real one (the “login via Facebook” button was omitted, presumably so the crooks didn’t need to handle that option as well as cloning the Instagram page).

Alon

a U2F device – like a YubiKey – would should side-step phishing entirely by detecting the mentioned “Unexpected domain name”.

Also, I’m working on an app that constantly monitors your instagram account (among others), so unless the attacker locks you out of your account – which they very often don’t – you would be notified when someone else uses your phished credentials.

frontguard

Nice article. But what is the idea behind hiding the fake domain name in this blog? Won’t it help others to make a sense of evaluating real vs fake? And not restricting by verifying the genuity of the website by the country code in the website.

Paul Ducklin

I usually obfuscate the domain names in case like this, just to discourage people from taking a look.

It was a six-letter English word with one letter changed.

John Lord

The mention of “six-letter English word with one letter changed” reminded me of past discussions of “typo-squatting” domain names hoping to catch careless typers. You might refresh people’s memories about that if you run short of ideas for your column. Or even just mention it in one anyway, since you always seem to find interesting topics. Love your column!

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words!

We looked at typosquatting in a somewhat methodical (is that an oxymoron) way a few years ago. Might be worth revisiting now there are so many more top-level domains, as well as free domains and free web certificates.

FYI, you might enjoy these from back in 2011:

https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/typosquatting/

Claire Smuts

Did the scam address people by name? I see you redacted (presumably) a name next to “Hi”. Was just wondering since that is usually one of the other things to look out for.

Paul Ducklin

Yes, there was an Instagram account name under the brown “masking tape” that I superimposed on the image. To the best of my knowledge, the email address involved was the one officially associated with the account (i.e. it is where emails from Instagram itself would actually go) but that association would be easy enough to figure out automatically or to guess from existing spammers’ lists.

Michael Myers, Ph.D.

Other companies list an email address to forward phishing emails to, so their security people can go after the hacker, but I can’t find any on your site. Where do I send it? And yes, I always send all the Headers, so you can find them easily.

Paul Ducklin

The easiest way is probably “is-phish@sophos.com” (send the whole email as an attachment if you can – in Outlook you can just hit [New message] drag and drop the phishing mail from your inbox onto it).

You won’t get a reply because it’s an email account that is processed automatically but the submissions end up in the SophosLabs feed.

If you don’t think it’s a phish or scam but it is otherwise unwanted/unsolicteddodgy you can use “is-spam@sophos.com” instead.

Sue Medrano

There’s an Instagram DM phish/spam setup that I’ve been trying to unravel since my daughter fell for it, and it’s fascinating. There are multiple components of the attack and they seem to be attacking influencers.

They solidly locked her out of her account and it turns out that the DM she received came from another influencer who has been locked out of her account months ago.

After my daughter got locked out and complained about it on her personal account, some people reported to her that they were receiving from her account the same spam/phish DM. It was maddening that we couldn’t stop it or even report it adequately.

The attack starts with the DM and then they slide into what you’re describing. An interesting touch is that before they hit her up with the 2FA email, somehow using the link in the DM they got her to permit them to have proxy permissions to her gmail account. They created a filter to send all emails from Instagram to the trash, and were even careful to permanent-delete real IG once they got to the trash. They also had a filter to ensure their fake Instagram emails were leveled as Important.

The first email she got was like yours, but they “helped” her to initiate setting up 2FA on Instagram and email to them the code. They apparently also got her iPhone number too.

Once they took over her account and she was locked out, subsequent emails started giving her instructions to restore the account. I’m glad I found out what was happening before she followed those instructions – it was now an identity theft grab. Those emails were very well crafted.

This is what really bothers me:

You can’t follow Instagram’s instructions to report the situation to them if you can’t get to your profile and you don’t have the email alerts to respond to if they are sent to your trash and deleted. The only thing I could think of was to have her broadcast to her friends that they need to report her account. But it really bugs me that she’s hearing more and more stories from other influencers that they lost their accounts this way and they just gave up and started a different account. As their accounts continue to spew phishing spam.

I have been wanting to report this particular variant of the attack because it’s very well done and dangerous and apparently Instagram is doing nothing about it. A bunch of beauty influencers are not well prepared for something like this.

I’m still trying to find a way to alert Instagram about this use case. I’ve sent all of the emails to phish@instagram.com. Nobody seems to be curious about it.