We’ve written many times about ';--have i been pwned? (HIBP), a website run by security researcher Troy Hunt where you can check how many times your email address has shown up in data breaches.

Amazingly, the number of breached accounts that Troy has processed into his database over the years is just under 7 billion.

We’re not looking at 7 billion real accounts or even still-active accounts, of course, and we’re definitely not looking at 7 billion unique users, which would just about cover everyone on the planet…

…but the cumulative amount of breached data exposed publicly in recent years is alarming.

Fortunately, HIBP doesn’t have passwords for all those breached accounts, because well-run websites store your passwords in salted-hashed-and-stretched form, so that the original passwords can’t be recovered easily in the event of a hack.

The idea of storing a password hash instead of the actual password is that a hash can be used to verify a password, but can’t be reversed to recover the original password. A crook who makes off with 1,000,000 plaintext passwords has already won the battle and has no cracking to do. But a crook with 1,000,000 hashes still has to crack each one by guessing the password that computes to each hash.

💡 LEARN MORE: How to store your users’ passwords safely ►

Nevertheless, HIBP currently has more than 550,000,000 breached passwords in its database.

Those passwords actually match up with 3.34 billion accounts, given that each leaked password had been chosen by about six different people on average.

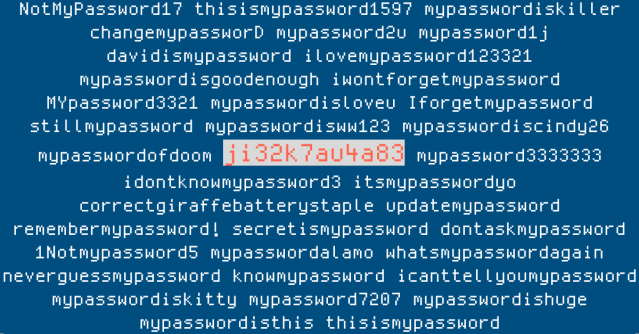

Some of us choose passwords like correctgiraffebatterystaple or QPDizG/V4gLtmlo30dXEHLC5, carefully crafted by hand or churned out automatically by a password manager.

Others of us aren’t quite so careful, and pick words that feel or sound secret – or perhaps actually are the word secret – but are well-known to crooks and therefore among the ones they try out first.

A few of us aren’t careful at all, and pick passwords simply because they’re trivial to remember and easy to type in, such as 1234567 or qwertyuiop.

With this in mind, you can probably guess which passwords top the HIBP list…

1. 0.69% 123456

2. 0.23% 123456789

3. 0.11% qwerty

4. 0.11% password

5. 0.09% 111111

6. 0.09% 12345678

7. 0.08% abc123

8. 0.07% 1234567

9. 0.07% password1

10. 0.07% 12345

11. 0.07% 1234567890

12. 0.07% 123123

13. 0.06% 000000

14. 0.05% iloveyou

15. 0.04% 1234

16. 0.03% 1q2w3e4r5t

17. 0.03% qwertyuiop

…but what about the best (or the worst) of the rest?

Robert Ou, a software developer from California, asked himself the same question and went looking for the answer:

The obvious explanation, you might think, is that the password ji32k7au4a83 was just someone battering away at the keyboard for a bit, so that, in a long list of passwords, it’s reasonable to expect that a few people ended up with the same mash-up of keystrokes by chance.

For example, qpeowpalsk20 looks kind of random, but we bashed it out by typing characters in a left-right-left-right pattern from the top three rows and outer two columns of a US keyboard.

It’s unlikely but far from impossible that two different users just clattering away on their keyboards in a similar way might come up with the same sequence.

💡 LEARN MORE: Fun ways to figure out fiendish passwords ►

A 12-character password from the set a-z0-9 presents 3612 different choices, for a grand total of nearly five million million million (4.744×1018).

But the qpeowpalsk20 password above comes from a far shorter set of possibilities.

We hit one of 12qwas at the left side of the keyboard, then one of the two characters on the same row at the other side of the keyboard, with six left-right repeats to get 12 characters.

The total number of different passwords using this approach is (6×2)6, or just under three million – a minuscule fraction (just 0.00000000006%) of the full password set we’d draw from if we used all the letters and numbers randomly.

Even so, you wouldn’t expect to see more than a few examples of qpeowpalsk02 in a list of 550,000,000 passwords, nor would you expect to see many examples of ji32k7au4a83.

But the mysterious password ji32k7au4a83 turns up 141 times in the HIBP list, compared to zero appearances of our own “randomly mashed” password.

Why so many hits?

The explanation of why one 12-character random-looking sequences turned up so often is both fascinating and depressing in equal measure.

The Twittersphere quickly figured out that the key sequence makes sense on what’s known as a Bopomofo keyboard.

That’s a keyboard system widely used in Taiwan for entering Taiwanese words as syllabic characters, constructing Chinese characters along the way as you type.

The name Bopomofo is a bit like the English word alphabet, which comes from the first two Greek letters, alpha and beta, or the Arabic abjad, named after the sound of the first four Arabic consonants. Bopomofo refers to the first four sounds in the Taiwanese syllabary (the name given to what is essentially an alphabet of distinct sounds) known as Zhuyin.

As Twitter fan and scientist Peter Barfuss, who’s from Paris, quickly pointed out:

The simple truth is that the unusual repetition of ji32k7au4a83 isn’t so unusual after all.

All is does is remind us that at least some users in Taiwan have exactly the same bad password habits as the rest of us.

In case you’re wondering, the Roman-character password mypassword was repeated 38,621 times in the HIBP data, while the abovementioned not-so-secret password secret came in 159th place, used 226,313 times.

What to do?

- Randomness often isn’t. The fact that a bunch of data “looks” random means nothing, and never can on its own. When you’re evaluating whether something is random or not, you need to address the whole history of that data, from how it was generated, where it was used, what happened to it next, and whether it was re-used inapproriately.

- Proper passwords matter. Mashing away at the keyboard is better than using your cat’s name, but as we explained above, you usually end up picking from a tiny fraction of the password space available if you use a decent random generator.

- Two-factor authentication is your friend. This story is a simple but very effective reminder of just how prevalent password breaches are, and that if you’re sending passwords to websites, even temporarily, you don’t have any control over how well or how badly they subsequently treat that password. A second factor, such as a one-time login code, makes account takeover much harder for the crooks.

💡 LEARN MORE: How not to write a random number generator! ►

(No video? Watch on YouTube. No audio? Click on the [CC] icon for subtitles.)