Mobile adware may not be as immediately harmful (and may not attract as much attention) as mobile malware, but that doesn’t make this nuisance category of software any less disruptive. SophosLabs took another look at a network of adware apps (first referenced in a report from Trend Micro) that managed to evade Google Play Market restrictions.

While Google took action and removed the apps listed in that report from their online store, they didn’t do it before the 84 apps had been downloaded to several million devices. We’ve found that a developer continues to push out new apps that engage in the same behavior. The collection of apps span the gamut from games, to utilities (like so-called ‘battery boosters,’ or television remote controls), to apps that modify the wallpaper or overlay “sticker” images on photos.

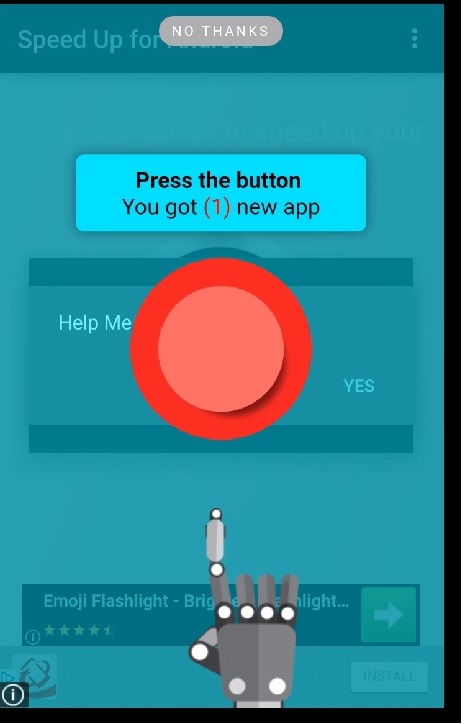

When users installed any of the apps, the app would initialize itself, and then set a background task that would launch full-screen ads on mobile devices — some when users engaged with the apps, others on a timer. Many ads promote other apps that share this behavior, and with each additional installation, the owner of the device could expect to be bombarded with even more full-screen advertisements.

We wanted to take a closer look at the older apps, and compare them to the newer apps. We also wanted to dig in to the network of websites that are being used to transmit the ad-downloading instructions to the apps.

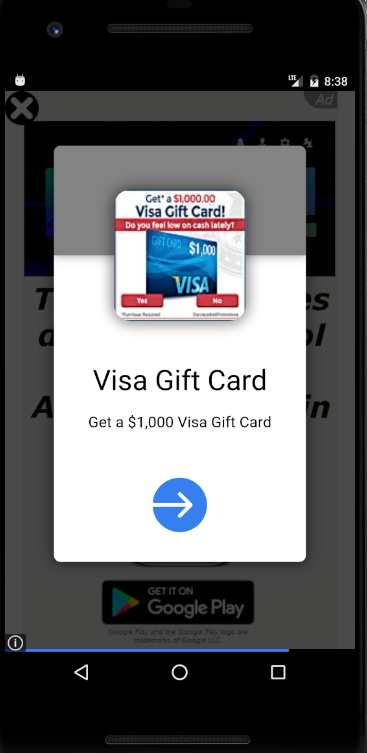

Illustrating the problem

After the user launches one of the apps for the first time, it immediately displays a full screen ad. In the example above, taken immediately after launching a car racing game called “City Racing Parking” (com.hemanlia.cityracing.parking), the app shows a full screen ad for a different racing app, “Racing Tour” (com.hemanlia.racing.circuit). Most of these apps pushed a full-screen ad touting another app even before showing the user the app itself.

From time to time, the ad code will decide a full screen ad isn’t intrusive enough, and while displaying a full-screen ad, overlays another ad on top of that one. Like some kind of advertising-themed version of the movie Inception, the ads keep going deeper, so it becomes increasingly difficult to simply use the device, navigating past the ads by trying to tap the tiny X that is supposed to close the ad window.

Some of the apps reportedly could delete their own shortcut icon and just run continuously in the background.

Several of the apps have a very limited function. For example, the extent of the functionality of the “sticker” apps is to add from 10 to 20 emoji-like small images to those made available in the chat app WhatsApp. It’s not hard to see that a user would have no reason to interact with the “sticker” apps (or even launch them a second time) once they’ve been used to add the “stickers” to WhatsApp. These apps, over time, display intrusive full-screen ads on an increasingly brief interval, and can do so even when other apps are in the foreground.

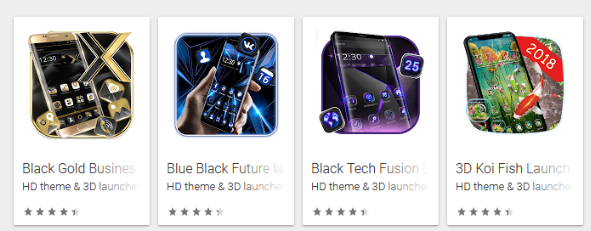

Many of the 84 apps that comprised the original set are, essentially, clones of one another. There’s very little cosmetic difference between them, aside from their names and the icons they use (and, in the cases of the sticker apps, the small number of what appear to be public domain images). Here are some examples:

Code analysis of Android adware

Analysis of these apps reveals nothing particularly sophisticated: the developers have not obfuscated their code, which is not especially complex. The source code of these apps contains normal components, such as code for launching the main app activity, receivers that trigger on certain events, and (of course) the ad loading instructions.

Beyond those, we also found code from legitimate third-party ad frameworks embedded in the apps:

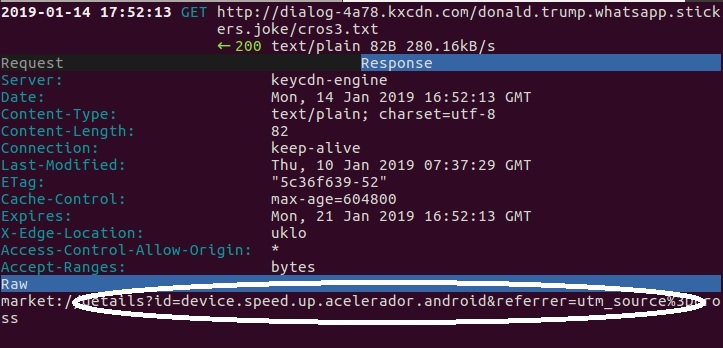

Most of the apps contain an embedded URL that that app calls as soon as it has been launched. The URL follows a consistent paradigm. (We’ve published a list of IoCs on the SophosLabs Github page to complement the IoCs published by Trend.)

http://[domain]/[package name]/cros[1|2|3].[jpg|txt]

For example, the code snippet below declares several ad URLs:

public CrossTerceraRed() {

super();

this.a = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros1[.]jpg";

this.b = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros1[.]txt";

this.d = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros2[.]jpg";

this.e = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros2[.]txt";

this.f = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros3[.]jpg";

this.g = "hxxp://goldapp-bcf4.kxcdn.com/com.oceanox.cyanogen.SUPERGAMESTVPORTUGUES/cros3[.]txt";

}

Each URL that leads to a JPEG file will result in a clickable image. Each matching URL that leads to a TXT file will fetch a name of the promoted app.

For example, the clickable images are:

The promoted app names can be seen by fetching the matching TXT files, as seen in the screen snapshot below:

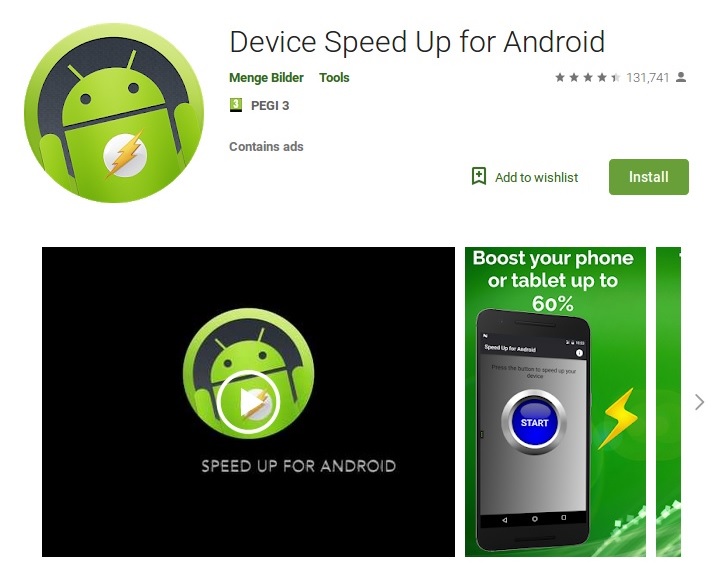

The apps promoted by the adware can be device ‘boosters’ or ‘accelerators’, installed by millions of users:

These apps, in turn, also pop up intrusive ads in an aggressive manner:

The promoted apps in turn promote other apps with full screen intrusive ad in a never ending cycle:

How do these apps earn their creators money?

Different mobile apps have different monetization models.

One of the popular monetisation models allows developers to earn money whenever users click ads. The revenue depends on a number of ads displayed (known as impressions) and also on a click through rate (CTR), which is number of clicks out of all the ads displayed to the user.

This model directly motivates developers to display full screen (interstitial) ads, thus driving a higher CTR. The rate of CTR for such full screen ads reaches 5% out of all ads displayed to the user.

Needless to say, a set of aggressive apps with millions of installs bears potential to generate sizable revenue for the developers.

The abuse of monetisation models promotes useless apps instead of useful ones, clogging Google Play store with the apps that no one really wants.

How does an adware app get so many downloads?

Many of the apps have been downloaded thousands of times. The most-downloaded app was TV remote, which had been downloaded 5 million times prior to the app being removed from the Play Market.

First, it’s absolutely trivial to build an adware app, hence the entry barrier is very low.

Second, there are no obvious malicious telltale signs in such apps, making it a challenge for the Google Play store defenses to single them out.

Finally, the apps themselves tout other adware-infested apps in these rapid, full screen popups. If a user installs two or more of these apps, they begin to see proportionally more ads, and are exposed to many more promotions of other apps that use these methods.

Conclusion

Ads are an easy way to earn money that is also welcomed by free app users if the ads are placed in non intrusive way of user experience. Google AdMob developer site clearly states that, “ads should not be intrusive and ad placement should not interfere with navigating or interacting with app content, example: an interstitial ad (full screen ad) triggered every time a user clicks within the app.”

Adware apps are inexpensive to develop, requiring minimal development effort, and get past security-related code review as they only need minimal permissions, thus guaranteeing a relatively high return on investment.

As Google tightens its grip on other parts of the Android ecosystem, we do anticipate more and more malware authors migrating towards adware, ad-fraud and click-fraud activities.

While all the apps mentioned in Trend’s original blog post have already been removed from Google Play store, they may remain present on users’ phones, and obviously, these new ones continue to appear. Sophos Mobile Security for Android will detect and block all these apps under the definition Andr/HiddAd-T. Our additional IoCs are published on SophosLabs’ Github page.

John C

Play store is filled with these kind of adware. Google should do more to get rid of these crap. Good we are seeing these highlighted by security firms now.

Emily

these should be called as Trojan not as adware, they don’t deserve a place on any phone

David Bradbury

Glad I stuck with my Windows 10 phone. Not looking forward to the Android transition later this year. I think the first app to install will be Sophos Mobile Security.