Chrome 70 comes out today.

Most people who use Google’s popular browser will receive the update, and either won’t realise or won’t especially care about the changes it contains.

Next Tuesday, Firefox 63 will be released, and much the same thing will happen for users of Mozilla’s browser.

But one of the changes common to both those products, which have a huge majority of the market share amongst laptop users, may matter very much to a small but significant minority of website operators.

Chrome 70 and Firefox 63 will both be disowning any web certificates signed by Symantec.

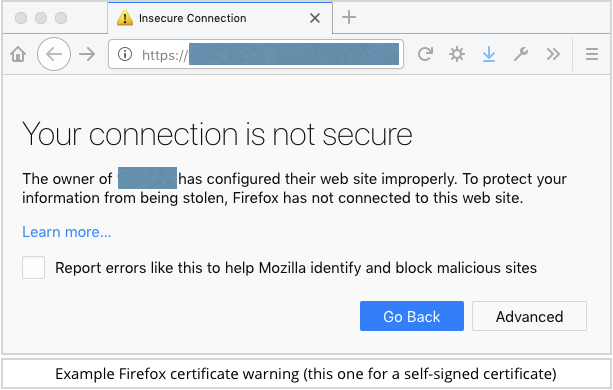

From this month, anyone with Chrome or Firefox who browses to a web page “secured” with a Symantec certificate will see an unequivocal warning insisting that the site is insecure:

Unless your website is really mainstream and well-known, you should assume that almost all users confronted with a warning of this sort – especially in this surveillance-conscious age – will simply hit the back button and try the next website in their search results.

Simply put: we’ve been teaching people not to ignore certificate warnings for years; browsers have made it harder and harder to sidestep the warnings, in an effort to make users take notice; and people have been taking notice.

Anything that suggests a website might be up to no good – even if the warning is down to a configuration mistake rather than any actual malevolence – is a giant turn-off to prospective visitors, and causes the search engines to mark you down.

There shouldn’t really be any Symantec certificates left in use – Symantec sold its web certificate businesses (it owned several well-known brands) to a company called DigiCert back in 2017, and DigiCert has been reissuing old Symantec certificates since then.

Anyone with a not-yet-expired Symantec certificate can replace it for free – so if you’re one of them, don’t leave it any longer to do your renewal.

You can expect a visible downturn in traffic if you don’t.

Update. An alert reader (see comments below) pointed out that Mozilla recently deferred this change until “later in the year” to give everyone a bit more time. As Mozilla says, “It is unfortunate that so many website operators have waited to update their certificates, especially given that DigiCert is providing replacements for free.” [2018-10-16T17:40Z]

Here’s a quick overview of how we got to this point…

Why do we have web certificates?

Web certificates put the S in HTTPS, and the padlock in your browser’s address bar.

Without HTTPS, anybody could clone anyone else’s website at any time, making it look indistinguishable from the real thing except for booby-trapped or fake content here and there, and you’d be hard pressed to tell the difference.

But when an HTTPS connection is set up, your browser receives a web certificate up front that vouches in some way for the fact that the site really is owned and operated by the company it claims to represent.

Why do we need to get web certificates signed?

Anyone can create a web certificate, and they can put in any ownership information they like.

This is known as a self-signed certificate – jargon that means you are vouching for yourself.

If you only expect three or four people ever to use your site, you could prove to them individually that you really were the person who created that certificate – you could meet up in person, for example – and thereby build a small but strong web of trust.

But that sort of approach is no good if your goal is to attract thousands or hundreds of thousands of visitors from all over the internet, because you can’t possibly reach out in person to all of them in advance.

The solution is to get a company known as a CA, short for Certificate Authority, to vouch for you by signing your web certificate using their web certificate.

Before the CA vouches for you, it’s supposed to do some basic checks to satisfy itself that you really are authorised (and able) to operate the website that the certificate is for.

Basic CA checks, such as those down by the free CA Let’s Encrypt, are limited to testing that you are able to log into and administer the relevant site. For example, before signing your certificate, the CA may tell you to add a random, unpredictable string of text to a new and specially-named page on your site. If the relevant text appears in the right location within a reasonable time, the CA will assume you have full access to the site and will sign your certificate. More expensive certificates, denoted EV for Extended Validation, require additional checks such as looking at company registration records, validating published contact details with real phone calls, and requesting physically signed documents. In short, CAs aren’t supposed to sign certificates only on the say-so of the submitter.

Who vouches for the CAs?

A certificate signed by a CA still isn’t enough – your browser itself needs a list of known-good CAs that it’s prepared to trust to sign certificates for the websites you’ll be visiting.

So every browser includes a list of trusted “root CAs” whose certificates it will accept.

Some browsers, such as Edge and Safari, rely on a list of trusted roots supplied by the underlying operating system; Chrome on Windows and macOS uses the operating system’s certificate store, plus its own list of tweaks to disavow CAs that Google no longer trusts; Firefox on all platforms and Chrome on Linux use Mozilla’s curated list of known-good CAs.

In simple terms: you create an HTTPS certificate to vouch for your website; you choose a CA to vouch for your certificate; and your browser vouches for the CA.

This is what’s known as a chain of trust, and the browser (or your operating system’s certificate store) is where the chain is anchored.

What happens if a CA goes rogue?

If a CA loses the trust of the community, then the ultimate sanction is for the community to agree to remove that CA’s own certificates from the list of known-good roots.

That’s quite rare, because the side-effect of ejecting a CA’s certificate from every browser is that every certificate ever signed by that CA is implicitly disowned, so every website using a certificate from that CA immediately becomes untrusted.

That’s what is about to happen to Symantec certificates in Chrome and Firefox.

Why is this happening now if Symantec sold its CA business last year?

The community became dissatisfied with Symantec’s CA business over a lengthy period.

The company had acquired a number of CA sub-brands (Thawte, GeoTrust, and RapidSSL), and the community wasn’t happy that the parent company was keeping strict enough tabs on how the various parts of its CA business were operating.

Mozilla has published a list of known issues that makes informative reading for anyone who’s interested in what a CA should and shouldn’t be doing…

…but the final outcome is that Symantec sold off its CA business to DigiCert, and DigiCert agreed a timeline for replacing any existing Symantec certificates, thus helping the community get off to a fresh start.

Why is this suddenly worth a news story?

Plenty of time was agreed for the transition from Symantec to DigiCert.

Indeed, many existing Symantec certificates expired during this period, and needed renewing anyway.

Symantec and DigiCert have both been clear and open about the process that affected certificate holders need to follow, and replacement certificates are issued free of charge.

However, a small but significant minority of website owners still haven’t realised that their existing web certificates will essentially be “visually condemned” by both Chrome and Firefox this month.

What to do?

If you run any websites that still have web certificates where the CA who signed it was Symantec or one of its subsidiary brands (Thawte, GeoTrust, and RapidSSL), replace the certificate right away.

If you don’t renew or replace your certificate, you can expect a visible drop-off in traffic over the next couple of weeks: users who suddenly see security warnings when visiting your site are likely simply to shop elsewhere instead.

You can buy a new certificate from a completely different CA, or contact DigiCert, who bought up Symantec’s CA operation.

This is a really easy issue to fix – it should be no more complicated or time-consuming than renewing your driving licence or getting a new library card when you move house.

But it could be an expensive issue to ignore, if you rely primarily on search engines and links from other sites to bring in visitors and to generate new business…

…and who doesn’t?