By Andrew Brandt

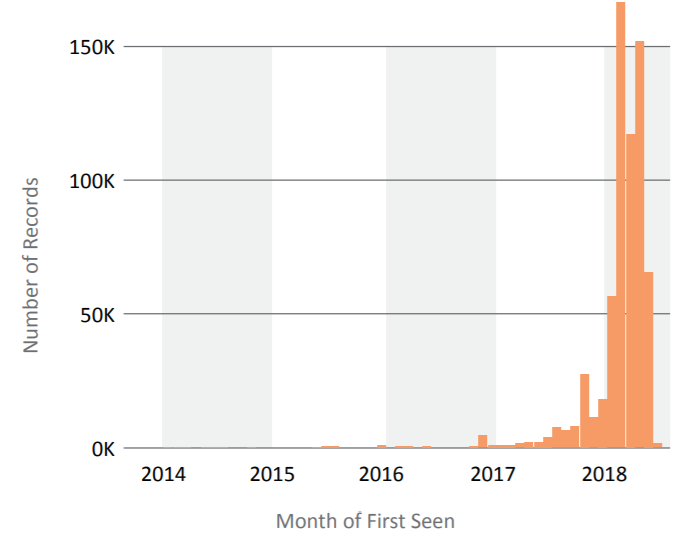

Despite the wild fluctuations and severe drop in the value of many cryptocurrencies over the past year, the not-so-advanced, very persistent nuisance of cryptomining continues to grow and spread into virtually every arena of technology.

While this doesn’t seem, on its face, as much of a threat, the act of cryptomining does have far-reaching effects beyond the very, very slight enriching of some enterprising and somewhat desperate people.

SophosLabs, along with a host of other security companies, contributed to a report issued this week by the Cyber Threat Alliance, an industry group that seeks to enhance the protection of everyone by giving companies in the cybersecurity space a place to work together towards common goals and share information about threat actors and campaigns.

Among the key findings in the report, we discovered that cryptomining spiked in the past year, with the number of unique mining apps constantly on the rise. The act of cryptocurrency mining can greatly stress both machines (to the point of mechanical failure) and the energy grid itself (where power generation utilities are starting to crack down on boiler room mining operations), while the people who benefit most from cryptominers only make a tiny fraction of the value of the energy expended in the process of mining.

As a result of the high-and-growing amount of work involved to earn a progressively smaller (as time goes on) slice of the cryptocurrency pie, many people involved in cryptomining are increasingly turning to hijacking the use of devices owned by other people as a way to gradually increase the output of their currency miners. We’ve started to refer to these narrowly-focused criminals, as well as their tools, as cryptojackers. Unfortunately for the victims of cryptojacking attacks, the costs in terms of power consumption, repairs, or lost performance can be extremely high, and the victims (of course) reap none of the benefits of the work they’re doing for the criminals.

Patching to prevent cryptojacking

One finding in the report is that a large number of enterprise networks continue to lag behind installing key operating system updates that close exploitable loopholes cryptojackers take advantage of. At least two major cryptojacking malware familes, called Adylkuzz and Smominru, are known to use the EternalBlue exploit to spread their miner code laterally within large organizations. The patch to disable the EternalBlue exploit in modern Windows systems was first published by Microsoft in March, 2017. There is literally no excuse for not installing a Windows update that’s more than 18 months old, unless that machine will never be connected to a network.

As some users become aware of the problem of cryptojacking, the tools used for cryptojacking have become more sophisticated, and better at evading detection through a combination of stealth and guile. Miner malware such as PowerGhost uses many of the techniques pioneered by APT threat actors to spread laterally within networks and remain under the radar, even going so far as to disable Windows Defender and to remove any competing cryptomining software it might find on a machine it has infected.

But in other systems, the problem of updating can be tricky. For example, some of the crews who operate the Mirai botnets have been experimenting with using exploits that target networked devices such as routers, wireless access points, cable/DSL modems, and network-attached storage boxes to install cryptomining code onto the so-called internet of things. We and other members of the CTA have observed increasing volumes of automated attacks of this nature hitting honeypots and public-facing servers. These devices are harder to update, and in some cases, they represent a physical manifestation of abandonware, as their manufacturers close up shop or the products hit their end-of-support.

We’ve also seen the rise of browser-based cryptomining, which means that anyone who can add a line of code to a web page can become an illicit cryptominer. Vulnerable plugins in popular content management systems such as Joomla or WordPress, which have been dogged for a long time by abusive site hijackers, now are exploited to add these new Javascript-based cryptominers to the footers of websites, turning every site visitor’s computer into a (temporary) cryptojacking victim.

And the browser-based cryptojackers have managed to worm their way into mobile apps as well, turning smartphones into mining mules, which causes overheating and battery consumption issues that are hard for the owners of those devices to trace back to their origins.

Costs borne by victims

The return on investment for cryptomining is miniscule, so there’s a huge incentive for cryptojackers to constantly try to find new ways to spread their miner software to more machines at the lowest possible cost — to them. But the costs to victims are much worse.

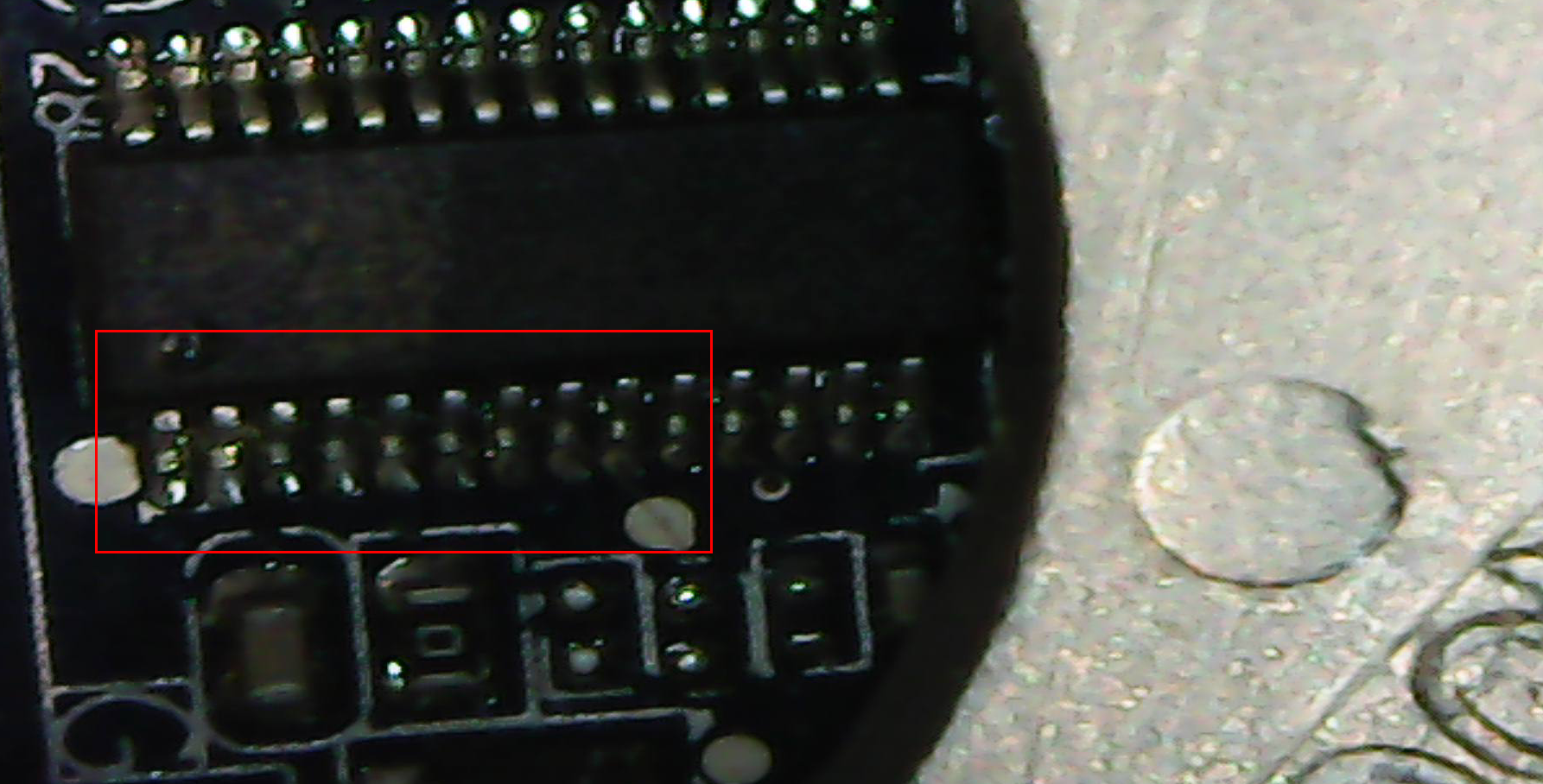

This is Jack, who was a loyal test subject in my malware lab until last year.

This old Dell D620 laptop led a burdened life of being deliberately infected with malware over and over again, and then met a tragic fate when it fell victim to a Monero-based miner I installed on it. The malware turned the laptop into a lump of useless plastic and ruined solder joints after it pegged the processor at 100% for several hours, until the cooling fan built into the device finally failed, and the laptop overheated in dramatic fashion. And I had just bought new RAM for it, too!

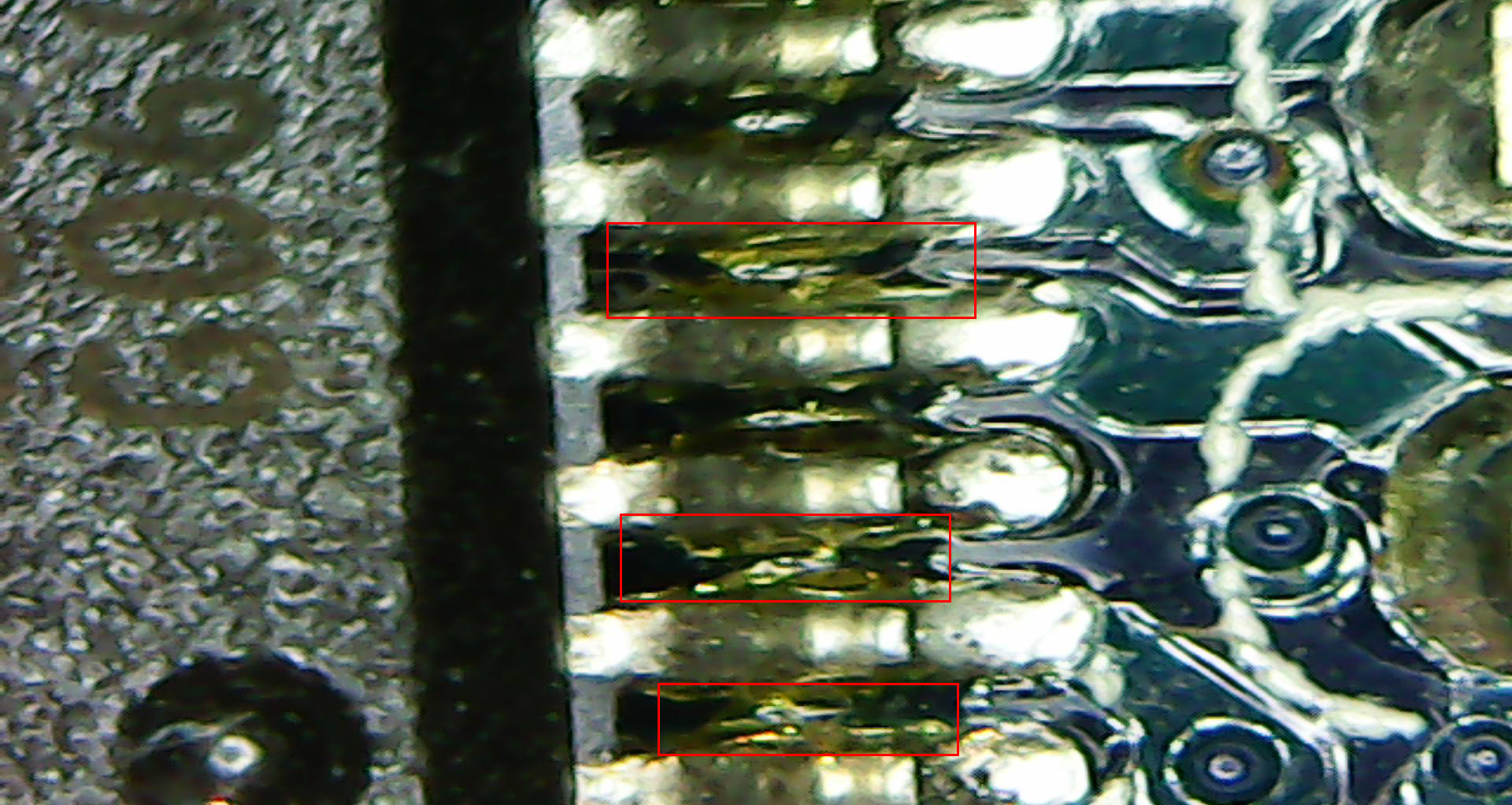

The motherboard on this laptop is now shot because there are dozens of tiny electrical shorts that were created when the motherboard got hot enough to melt some of the solder joints that were used to attach memory controller chips to the motherboard directly adjacent to the CPU heat sink. Here’s a closeup shot of one of the controllers that seems to have been damaged by the heat.

I’ve taken some micrographs of a few of the places where it appears the solder flowed between the pins of integrated circuits mounted to the board. It’s not a kind of problem a tech in the IT department can solve, short of replacing the entire motherboard, which in this case is not possible due to the age of the device.

In addition to creating costly repairs, like this, cryptomining is also reportedly responsible for some power utilities instituting “no cryptomining” policies and others have had to raise rates as demand for electricity to power illicit cryptomining operations skyrockets.

Overall, the problems caused by cryptojacking software and illicit cryptomining are only set to increase. You can read the full report here.