By Gabor Szappanos

A new study of weaponized office documents reveals that, in an uncharacteristically sudden and thorough shift of criminal priorities, a range of exploits formerly used (in some cases, for years) in those malicious documents have been scrapped.

In a matter of a few months around the beginning of 2018, the creators of tools used to mass produce maldocs made a clean sweep, and now only provide the ability to embed newer exploits. Criminals use these tools, known as builders, to manufacture malicious Word, Excel, Powerpoint, PDF, or RTF documents that make up key elements of targeted attacks, which they then spread primarily via email.

Over the past two years, the makers of these builder tools offered a relatively consistent menu of exploits from which criminals can choose, à la carte, the ones they wish to embed in their maldocs; As detection of older, more established exploits incrementally improve in security tools, the builder-makers typically remove those exploits gradually from their offerings. But we’ve never seen such a radical abandonment of existing exploits (and, in some cases, of the tools that implement them) in such a short period of time.

Largely as a result of the automated nature of these builders, researchers can identify signature characteristics that individual builder tools embed into maldocs as a way to establish the provenance of a given maldoc.

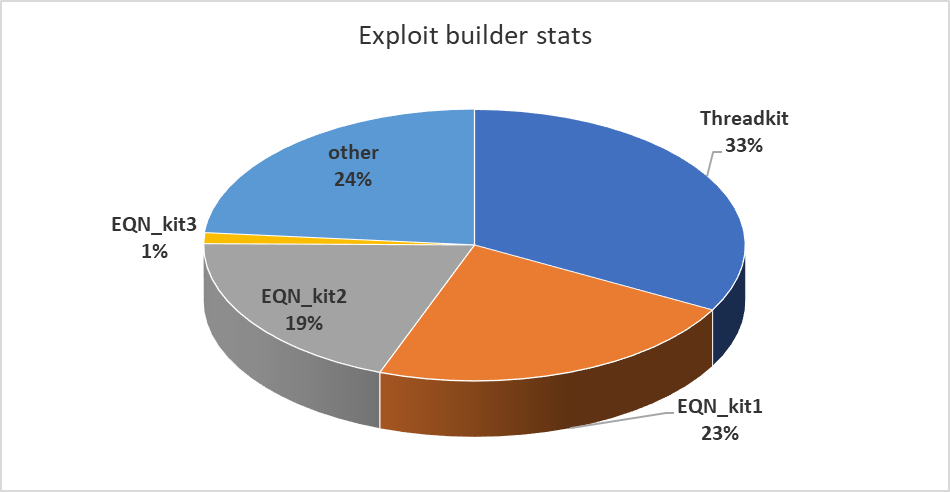

In the first quarter of this year, we found that just four exploit builder tools were responsible for the generation of more than three quarters of the in-the-wild maldocs we investigated. One builder, which calls itself Threadkit and sells for around $800 on Russian-language online criminal marketplaces, was used to create about a third of the malicious document files we analyzed.

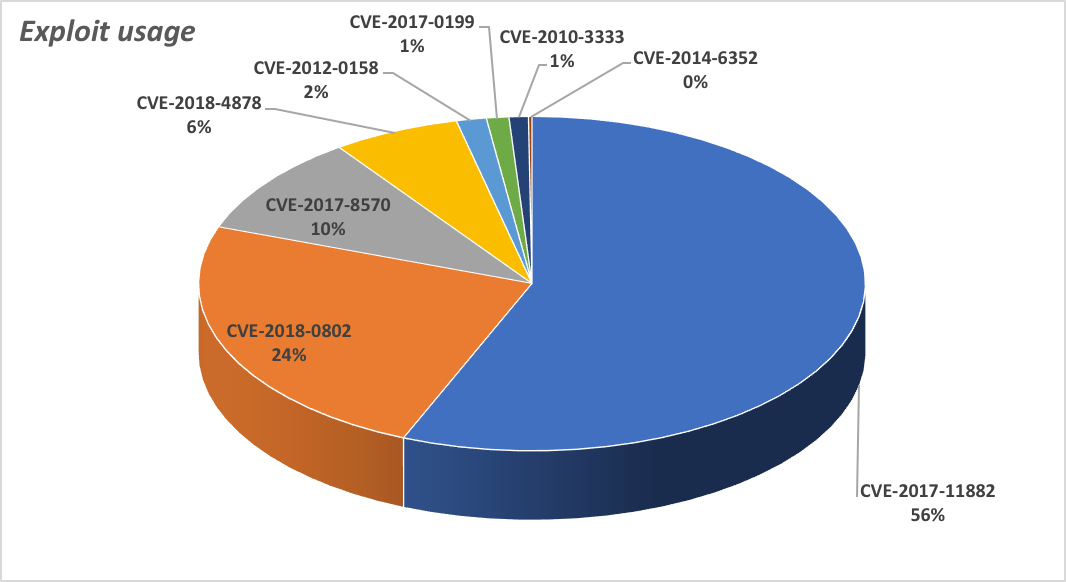

Within a few months of the beginning of 2018, the most popular exploits, including the Ole2Link vulnerability (CVE-2017-0199), completely disappeared from maldoc attacks. This vulnerability, coincidentally, broke the four-year dominance of the CVE-2012-0158 vulnerability (a buffer overflow in the MSCOMCTL.OCX ActiveX control) last year, and merely 6 months later, joined the obsolete old bug in the dustbin of history.

Accordingly, some of the older builder tools, with names like Microsoft Word Intruder or AKBuilder, that implemented these older exploits also vaporized.

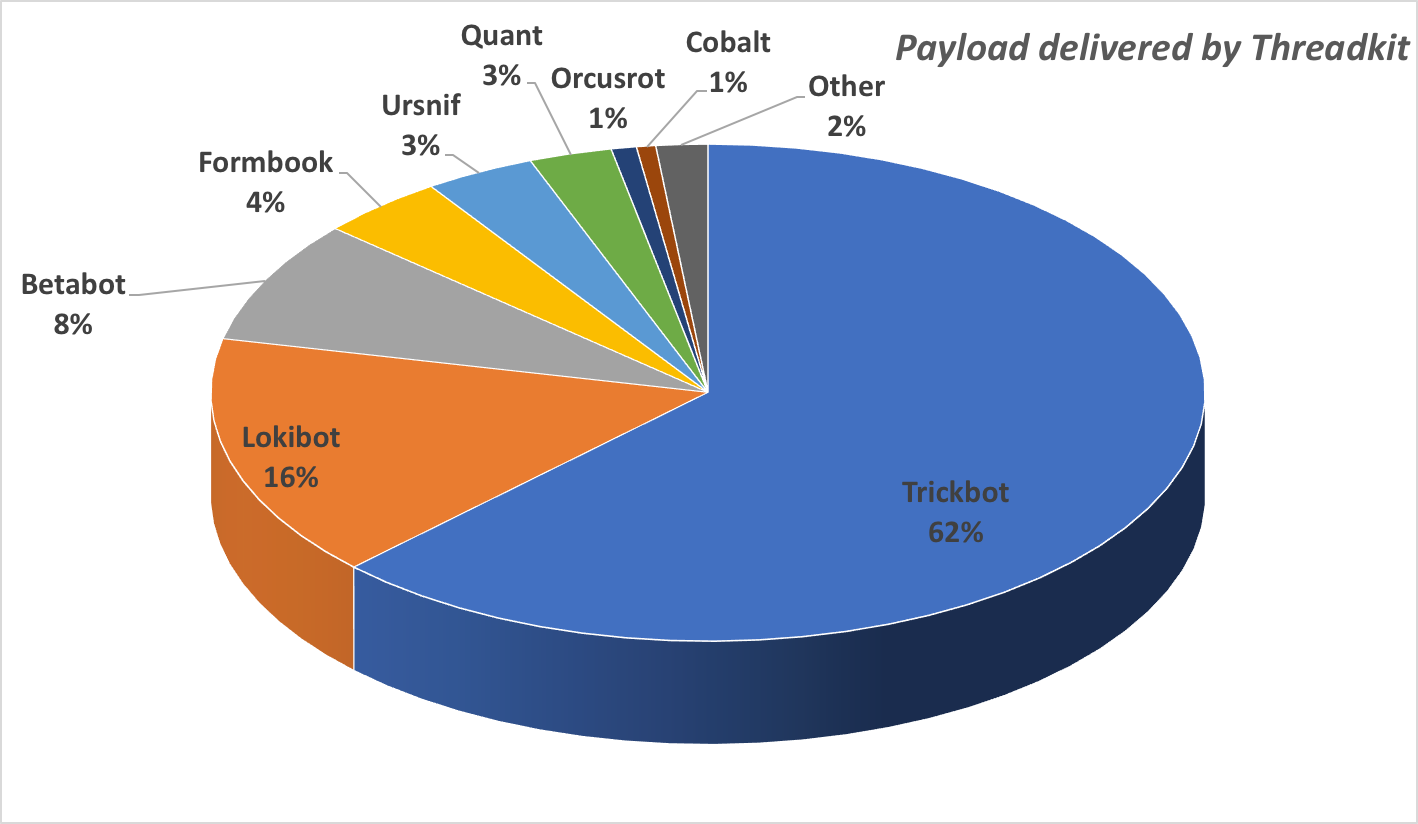

Threadkit, for example, supports a wide range of exploits; In maldocs we’ve seen that we’ve attributed to originate with this builder, the documents (primarily rich text files, or RTF) embed exploits tied to at least four separate vulnerabilities within the same file, as shown in the graphic below.

These exploit blocks trigger at least two stages of batch file installers, which in turn execute the final executable payload Threadkit is tasked with delivering. This redundancy may help with the infection success rate.

Likewise, contemporary maldoc attacks have been moving away from embedding malware directly into office documents. In the first quarter of 2018, the maldoc samples we investigated were all droppers, with the executable payload embedded within the document itself. But we’ve observed criminals switch gears to so-called “fileless” methods that invoke Windows-specific tools like PowerShell to download and execute the malicious payload, which makes the maldoc smaller in size, and more challenging to detect.

The exploits that these newer builders seem to prefer include a vulnerability in the Equation Editor feature in Microsoft Office (CVE-2017-11882) which, back in November, 2017 when Microsoft first published details about it, the company indicated had not been exploited in the wild.

Since then, we’ve observed this exploit embedded in at least 56% of the samples we looked at. The vulnerability does not require users to enable Macros in the Microsoft Office suite in order to execute code. Another vulnerability in Equation Editor, CVE-2018-0802, was used in 24% of maldocs we investigated, meaning one or another of these Equation Editor vulnerabilities were embedded in at least half the maldocs in our analysis.

For instance, the NebulaOne builder permits its users to configure and embed this exploit into a Word document.

Microsoft’s updates simply remove the Equation Editor from the system.

The even more recent Flash vulnerability (CVE-2018-4878) also made an impact, landing in fourth place on our chart, indicating that fresh vulnerabilities quickly make their way into the builder ecosystem.

We’ve also observed specific builder tools that appear to be tied to, or have exclusive distribution deals with, individual malware campaigns. For instance, Threadkit seemed to have an exclusive deal to deliver the Trickbot banking malware for a period of time, though it was also observed delivering the Lokibot RAT and a broader range of malware families. The EQN_kit1 builder delivered, in roughly equal proportions, the Fareit and Lokibot malware families, and to a lesser extent the XTRat and Remcos malware.

The good news, at least, is that patches have been available that prevent the majority of these attacks from succeeding for at least half a year, and exploit prevention technologies in Sophos and other companies’ products mean the exploits themselves are less effective with each passing day.

The bad news is that, obviously, the criminals seem to think that the mere availability of patches doesn’t mean that people will install them, and they may be right. All of this should be considered a call to arms for IT administrators or, frankly, anyone who uses a Microsoft Office suite on the Windows platform: Update your systems and the software that runs on them without delay, or suffer the consequences of one person’s mistaken click on the wrong office document.