The Australian government wants to force companies to help it get at suspected criminals’ data. If they can’t, it would jail people for up to a decade if they refuse to unlock their phones.

The country’s Assistance and Access Bill, introduced this week for public consultation, strengthens the penalties for people who refuse to unlock their phones for the police. Under Australia’s existing Crimes Act, judges could jail a person for two years for not handing over their data. The proposed Bill extends that to up to ten years, arguing that the existing penalty wasn’t strong enough.

The Bill takes a multi-pronged approach to accessing a suspect’s data by co-opting third parties to help the authorities. New rules apply to “communication service providers”, which is a definition with a broad scope. It covers not only telcos, but also device vendors and application publishers, as long as they have “a nexus to Australia”.

These companies would be subject to two kinds of government order that would compel them to help retrieve a suspect’s information.

The first of these is a ‘technical assistance notice’ that requires telcos to hand over any decryption keys they hold. This notice would help the government in end-to-end encryption cases where the target lets a service provider hold their own encryption keys.

But what if the suspect stores the keys themselves? In that case, the government would pull out the big guns with a second kind of order called a technical capability notice. It forces communications providers to build new capabilities that would help the government access a target’s information where possible.

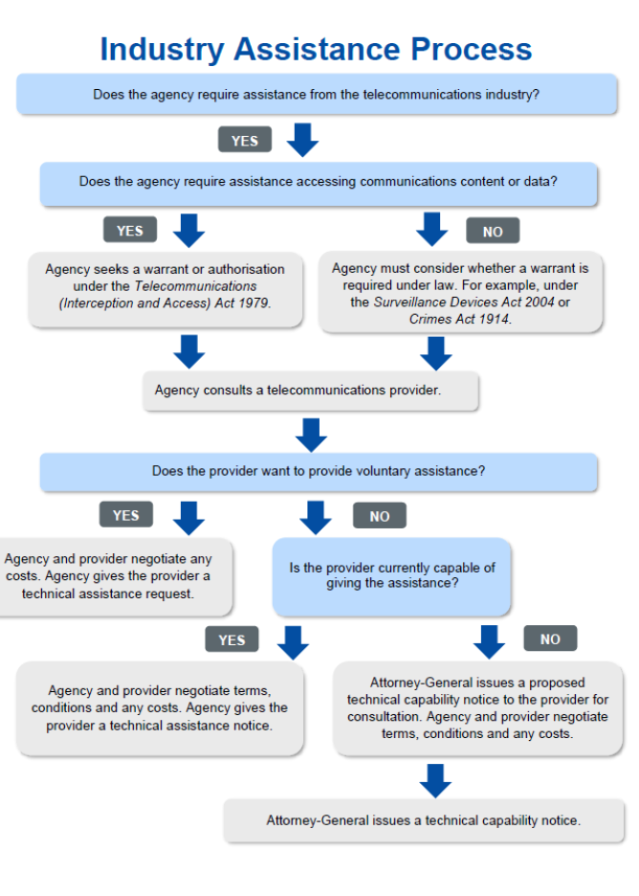

In short, the government asks companies whether they can access the data. If they can’t, then the second order asks them to figure out a way. Here’s a flowchart explaining how it works.

No backdoors

The government’s explanatory note says that the Bill could force a manufacturer to hand over detailed specs of a device, install government software on it, help agencies develop their own “systems and capabilities”, and notify agencies of major changes to their systems. In short, it would force communications providers to work extensively with the government to gain access to a target’s data where it was in their power to do so, and it would also compel them to keep all of this secret.

What if the communications provider doesn’t want to help? Then they could face penalties from the government, or “injunctions or enforceable undertakings”.

There are a few things that the Bill doesn’t allow. The government can’t force a company to build weaknesses into a product, or stop it from fixing those that it finds. That rules out encryption backdoors, then. Neither can it access information without a warrant.

However, the proposed legislation also creates a new class of access warrant that lets police officers get evidence from devices in secret before the device encrypts it, including intercepting communications and using other computers to access the data. It also amends existing search and seizure warrants, allowing the cops to access data remotely, including online accounts.

The backdoor war

In proposing this legislation, Australia joins a complex and heated debate about the role of encryption in the tech business. The Bill effectively rules out the inclusion of encryption backdoors, but seeks help from as many people as possible to get at the data, using a variety of loosely-defined methods.

Many services such as Snapchat don’t use end-to-end encryption, meaning that a government could use legislation like this to make it hand over a user’s encryption keys.

In this sense, it mirrors the UK’s Investigatory Powers Act, which asks telecommunications companies to remove electronic protections where possible. It also parrots FBI officials, who have said that they aren’t asking for encryption backdoors but that they do want vendors and service providers to break it where necessary.

The tensions over forced decryption have played out across the globe. In the US, Apple has tussled with the FBI in court over its unwillingness to help the feds break into its devices.

On the other side of the world, Russia blocked privacy-focused messaging company Telegram after it failed to hand over encryption keys that protect its cloud-based chats. However, Telegram also offers ‘secret chats’ for the extra-paranoid, which support end-to-end encryption, and the company couldn’t hand over those keys even if it wanted to.

There are two sides to the encryption argument. Security advocates including Sophos argue against the use of encryption backdoors, warning that criminals could discover and use them. Privacy advocates like Telegram founder Pavel Durov don’t like backdoors or forced decryption because they don’t want the authorities overstepping their bounds.

On the other hand, the authorities want to get at encrypted data somehow because they want it to stop criminals such as child abusers and terrorists. The latter have been known to use the Telegram service to plan their attacks.

The flurry of legislation around the world addressing this issue is a product of that complex debate. It also highlights the disparity between the legal system, which moves at a snail’s pace, and the technology world, which moves at the speed of light. One thing is for sure – it is a debate that is far from over yet.

Anon

Certainly a complex subject but I feel like Australia is going down the wrong path here and it’s disappointing to see.

ejhonda

Australians appear to still be living in a penal colony.

Michael Webb

Interesting read Danny…. I believe you nailed it at the end. “The flurry of legislation around the world addressing this issue is a product of that complex debate. It also highlights the disparity between the legal system, which moves at a snail’s pace, and the technology world, which moves at the speed of light.”…. By the time the law is ready for duty…the tech will be outdated.

Habeas Corpus

Good article.

mike@gmail.com

I may be in the minority on this, but I steadfastly hope that government wins this one.

AJ Cardwell

Why?

Mahhn

I suspect it’s his job in the corporation, er government. To manage the cattle, er secure the consumers, er, protect the citizens.

Tron

“I forgot my password, I thought this password would work, but it doesn’t work. Oh well.”

How to deal with this? Will there need to be a new branch of ‘thought police’ that just knows if you legitimately forgot your password or not?

I guess that means pretty much every senior citizen that forgets their password will be spending the rest of their living days in a new type of “retirement home”.

Pretty scary stuff, but nothing irritates totalitarian / big-brother / thought-police type of governments more that not having 100% total control over its subjects.

What’s next, having a government mandated security camera installed in every room of every house that can be monitored at any time by some nebulous government agent/agency. (Oh but don’t worry, the video stream is encrypted, the agent is carefully trained and sworn to secrecy, and hey, if you are innocent, you have nothing to worry about anyway…. right?!?)

Paul Ducklin

The decision on whether you did or didn’t forget the password will, presumably, end up as a matter for a court, not for the police. I imagine also that the actual sentence a court would impose would depend on how serious the crime was that was under investigation, and that sentencing guidelines would take that into account.

Whether you like this approach or not, there are precedents for it in other parts of the law. For example, at least in the UK, if you won’t take an alcohol test when you are stopped under suspcious of drink-driving, you’ll be charged with refusing to submit to a test, and that’s an offence that’s as serious as top-level drink-driving. The reasoning is that if that were not the case, no one would ever take the test – they’d cop to the lighter charge instead. Simply put, if you don’t let yourelf get tested, you’re automatically presumed not only to be guilty but also to have failed the test as badly as possible.

Alex

There is only one problem. Alcohol test does not disclose private data. Smartphones often have very private and sensitive data. Do you want the cops to see the pics of your wife on nudist beach and laugh?

Paul Ducklin

The principle is the same: making the penalty for failing to comply with the law about evidence gathering commensurate with the penalty for the offence that the evidence relates to.

Jimmy

In the event of “intoxicated driving” there is other evidence that supports probable cause for the arrest(motor skills/alcohol odor/slurred speech). The breath test only determines the quantity of alcohol in your system so the court can decide the level of punishment. You can pass a breath test(blow below the legal limit) and still be convicted in most jurisdictions if the evidence from the “road side” tests show that your ability to drive was impaired. If you pass all of the “road side” tests with flying colors, getting a “refusal to submit” charge thrown out is easy(at least in the US), as there was no evidence of IMPAIRMENT which is required as probable cause to administer the breath/blood test in the first place.

Forcing someone to unlock their phone, because there isn’t ample evidence to secure a conviction without it’s data, is NOT the same.

Paul Ducklin

The law is not at all like that in the UK or (as far as I know) in any Australian state or territory. Your apparent sobriety may be relevant in sentencing but not in facing the charge in the first place. In Australian RBTs, for example, there is no “probable cause”. Every driver is stopped and tested. (There is a school of thought that this is a fairer way to do it because there is no fear or favour possible. Generally, everyone exercising the privilege of driving through a designated roadblock is stopped for drink and drugs tests, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, value of vehicle, flashiness of vanity plate, etc.)

If you fail the test, you fail, and you are breaking the law. If the test was correctly conducted on properly certificated equipment then you pretty much cannot contest it and you would IMO be well advised not to try. Like speeding, the offence is a statutory one. Your apparent sobriety, which there is no sensible way to prove but you may invite a court to infer, may be a mitigation but it is not a defence.

Paul Ducklin

Voting the comment down doesn’t make it untrue, folks -)

Will

I don’t get the sense that people are rating the accuracy of your statement with regard to impaired driving laws, but rather its relevance to the particular discussion at hand. I’ll say the idea of impairment checkpoints exist in the US as well (though they usually just question and don’t immediately test everyone), but I believe earlier comments were talking about individual stops where there had to be some reason for the police to pull you over in the first place. The next step after the stop is typically a sobriety test prior to BAC.

I understand your point about this simply making the penalty for not allowing the test or search greater than the likely (or even maximum) penalty for whatever might be uncovered. In that sense, I agree that the two are similar. Where the comparison breaks down in my opinion, however, is when you start to think about the privacy implications. A BAC test looks at one thing and there is little risk you’ll expose anything beyond that. Access to your device could provide authorities with all manner of things beyond the scope of their investigation that you may not want to share and you have to simply trust they’ll behave according to the scope of their warrant.

I’d also like to call out the fallacy of “no encryption backdoors” in this proposed legislation. Access to encrypted information by someone other than those authorized by the device’s user, even if it’s not a decryption key, is still in essence a backdoor. If the government installs software on the device or mandates the ability for them to access it (but not decrypt it), that’s still a backdoor.

Dennis van der Spoel

That is turning the world upside down. Innocent till proven guilty, remember. It’s up to the police to prove I am guilty, I should not be forced to prove my own guilt.

Paul Ducklin

Technically, it’s “the presumption of innocence” that backs the court system in most Anglo countries, which is not at all the same thing as “innocent until proven guilty”. (I assume you mean “unless”.) That’s why most countries allow things like arrest and remand (either on bail or in custody), which curtail your liberties by accepting that you might not actually be innocent.

And the police don’t do the proof. They just provide the evidence, at least in countries where the legislature, courts and police are independent (or supposed to be).

Anyway, there’s no need to rant at me – I am not actually expressing an opinion, just pondering on how we got here, and what precedents led the way. If you don’t like the idea of search warrants of any sort, that’s a matter to take up with your leigslature, state and federal.

Clive

Your opinion siding with this authoritarianism is what people dislike.

Paul Ducklin

I’m not siding with anyone here. (I think I find the new regulation “rather pointless”, TBH, and that it feels like the kind of law that, if used in anger, will surely end up doing little more than enriching the lawyers on both sides who will surely argue it round the houses and back again, through any number of future changes of government.)

Jasa SEO berkualitas

Swap to Indonesian

in the current situation, we are faced with the choice of personal data security or national security?

somehow the government always argues every time they want to access data privacy with national security.

Are you willing to exchange privacy with the promise of security and stability from the country?

Dave S

For more serious criminals that the police need evidence to get them off the street this Bill is something that is needed, but alas I feel this bill will be just another way The Australian Police Force can bully and dominate the individual citizens, minor crime or not.

Dennis van der Spoel

Dave, they aren’t criminals. They are not convicted of anything in a court of law. Innocent until proven guilty. These are innocent people we are talking about.

AJ Cardwell

I wouldn’t under any circumstances unlock my phone for the police. My paranoia tells be that if I did and they disappeared out of my sight with it would me I’d need to buy a new phone.

Paul Ducklin

Not under *any* circumstances? Even if a court warrant ordered you to do so?

If you refuse to let law enforcement search your house with a warrant they are entitled to force their way in. If you won’t open a safe when instructed by a court then they can break out the angle grinders…

The cops already have your phone, remember – they need the code because they can’t access it on their own. If it’s “buying a new phone” that is worrying you – you’ll be doing that anyway. If it has been lawfully confiscated and you refuse to unlock it when instructed, they’re never going to give it back, are they? Why would they? They’ll hold it in case they figure out a way in later on.

Dennis van der Spoel

The fact that they can lawfully confiscate my phone or search my home is an abomination. What’s mine is mine, and I have the right to protect my assets and privacy by all means necessary. It is a shame that innocent people get harassed like this.

Anonymous

In Victoria it’s currently an offence to not give police your passcode. You can be charged with “ hindering police”.

The problem is that cops can take your phone and delete evidence that might be favourable to you. It happened to me.

Robert Stoneking

A proposed technical capability notice is an order to generate a hacking/ ID theft tool. Who is criminally and civilly liable when it gets loose and millions are affected? The AG, the investigator requesting it, the company, or the government?

anon

As a fellow hacker this is good news. The Australian government has proven time and time again that they cannot protect the data of Australia citizens. If they want to mandate privacy laws over their own people, what’s stopping criminals from abusing it lmao?

Your country is ran by old men who do not understand the complexities of security and privacy.

Drakekoefoed

If I were in the phone business I would dump Australia. “This device is not for sale in Australia or other police states” Just what is -not- needed!

Paul Ducklin

Many countries have similar laws about what could happen to you if you fail to comply with a “search and seizure” warrant against your laptop or phone…

Not sure if anyone else yet has a 10-year maximum for “cryptamnesia”, though.

Dennis van der Spoel

Basic human rights are being violated by governments worldwide. I have a right to privacy, and my thoughts and communications are mine alone, save for the person I am communicating with. The government has no business on my phone or computer. There should be a stronger law that prevents agencies from accessing or tapping phones and computers, or snailmail for that matter.