At the recent DEF CON cybersecurity conference in Las Vegas, macOS security researcher Patrick Wardle did something that the responsible disclosure doctrine says is a bit naughty.

He “dropped 0day” on Apple’s macOS, meaning that he publicly revealed an exploit for which no patch is yet available.

Exploits against unpatched vulnerabilities are known as zero-days for short, or 0days for supershort, because even an on-the-ball system administrator has had zero days to get ahead of the game with updates.

In an ideal world, Wardle would have told Apple quietly first, waited until a fix was out – or a suitable deadline had passed that implied Apple couldn’t be bothered to fix the issue – and only then gone public.

Fortunately, as zero-days hacks go, this one isn’t super-serious – a crook would have to infect your Mac with malware first in order to use Wardle’s approach, and it’s more a tweak to an anti-security trick that Wardle himself found and reported last year than a brand new attack.

The word zero-day originates in the 1980s and 1990s software piracy scene, where crackers competed to be the first to hack a new game so it could be played illegally without paying. The speed of a crack was measured in the number of days after official release until the crack appeared, so that a same-day crack, known as a “zero-day”, was the ultimate achievement.

Wardle told Wired he pretty much found this zero-day “because I wanted to run out and surf and I was being lazy.”

The haste caused Wardle to make a copy-and-paste programming mistake that oughtn’t to have worked at all, yet bypassed Apple’s security checks instead.

This is a stark reminder that hackers and cybercrooks can succeed through dogged determination and a whiff of good luck, simply by trying things no one else had thought of before, or things that everyone else assumed would fail.

The trick he discovered means that a program already running on your Mac can click through on-screen dialogs on your behalf, even when those dialogs are supposed to act as speed bumps to acquire consent for security-related activities.

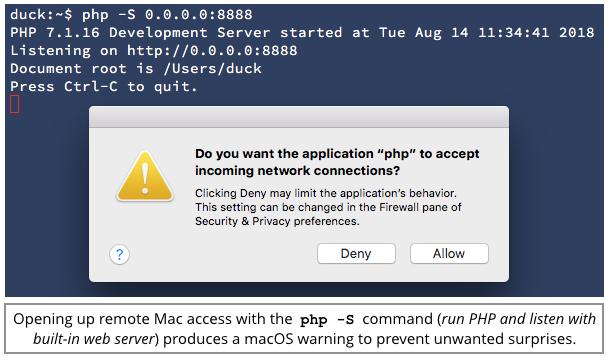

For example, if you have the Mac firewall turned on and a program tries to accept network connections from the outside, you will to see a warning so you realise what’s happening, and you need to approve it yourself:

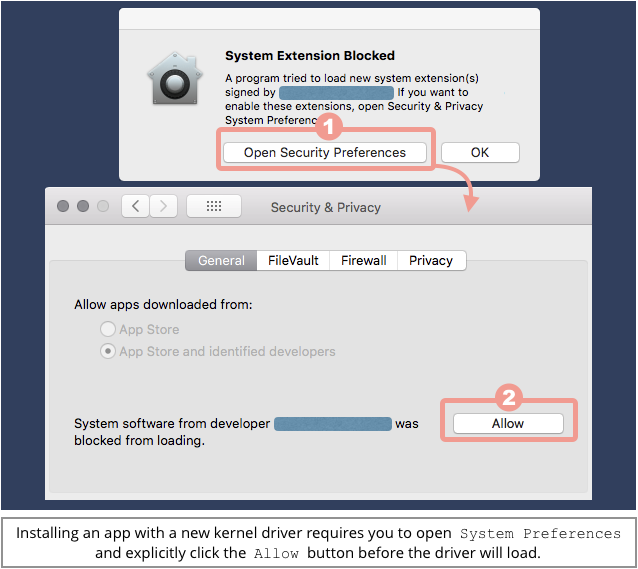

The same sort of thing happens if you install software that includes a kernel driver, a low-level component that gets loaded inside macOS and thus has access to the internals of the system itself.

Because apps with kernel drivers have much more power than regular apps – more, in fact, than apps that run with administrator powers – your Mac warns you before a new driver loads for the first time.

You have to click to authorise a new kernel driver, in addition to entering your password to install the app in the first place:

Wardle claims that you can reliably click past these speed bumps using a rogue app, even though Apple aims to make sure that this sort of dialog sticks around until a real user deals with it.

Wardle’s zero-day revealed

Clearly, any security warning that can simply be clicked through, rather than requiring some sort of authentication such as a password, isn’t particularly strict.

But if it’s supposed to be a warning, and it’s supposed to alert you to something an app isn’t supposed to be able to do of its own accord, then that selfsame app oughtn’t to be able to bypass the warning for you.

In 2017, Wardle spent time looking into just how careful Apple was at preventing apps from sneakily clicking past warnings that were supposed to demand user attention, and he found that there were surprisingly many ways for a rogue app to pretend to be a dutiful user.

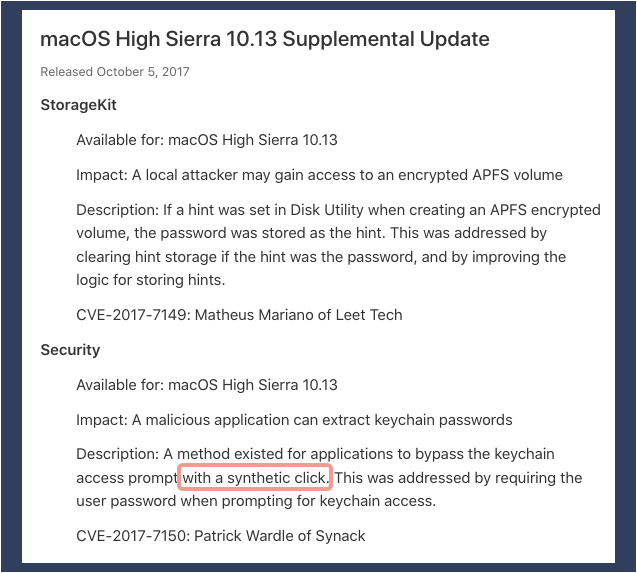

In fact, Wardle discovered a vulnerability that became CVE-2017-7150, patched in an official Apple update at the end of the year. (That update more notably patched Apple’s infamous “password stored as plaintext hint” bug.)

Apple’s intention, in the CVE-2017-7150 security patch, was to detect what are known as synthetic clicks in order to force user-facing popups to be dealt with by real users, not by mouse-clicking code running in the background.

Anyway, it was while preparing his 2018 DEF CON talk on the very issue of synthetic clicks that Wardle had his surfing urge.

The way Wardle tells it, he was writing code to generate a mouse click that that he assumed Apple would block, but accidentally coded his synthetic click as “generate a mouse down event followed by another mouse down event”.

Clearly, this can’t happen with a physical mouse, where the only thing you can do after pressing the mouse button down is to let it come back up, so his mouse simulation code shouldn’t have made any sense at all.

In theory, the double-mouse-down code should have been an irrelevancy that did nothing.

In practice, Wardle found that his code not only triggered a synthetic mouse click, but also went undetected.

In other words, it looks as though Apple’s anti-synthetic-click protection isn’t perhaps as generic as it ought to be – a bit like a cop who asks to see your driving licence to check its validity, sees it’s from overseas and therefore in an unfamiliar format, and decides simply to take it at face value and wave you through.

Note. Wardle’s DEF CON paper refers to the use of synthetic clicks to extract Apple Keychain passwords without you realising. As far as we can see, his new “zero day” does not revive this particular bug, because the dialog that Keychain pops up now always requires your password. Just clicking through is no longer enough to export passwords and keys from Keychain storage, assuming you have patched your Mac recently.

What to do?

If you’re a Mac user, there’s not a lot you can do until Apple issues an update to its original CVE-2017-7150 update.

This bug isn’t a show-stopper, of course, because it’s not a way to break into a computer, merely a way to skip sneakily past warnings that are routinely clicked through anyway.

Apparently, the next release of macOS, codenamed Mojave, will disallow many of the system features that make synthetic clicks possible in the first place – this might cause hassles for some legitimate but hackerish utility apps, but ought to be a general security improvement overall.

If you’re a programmer, remember that security is a journey, not a destination, and the patch you came up with today might not be effective next month or next year, so never rest on your cybersecurity laurels.

And if you’re a security researcher or a penetration tester, remember that security is a journey, not a destination, and attacks that get blocked today might not stay blocked for ever.