On 2 September, 2013, a California resident, Jesse T., was arrested and booked into the Sonoma County Jail.

As is standard procedure, police took his mugshot and his fingerprints. He was released 12 days later without being charged for a crime.

Jesse T. estimates that he went on to submit 100 applications for jobs in the electrical field, construction, manufacturing, and labor. He got nary a nibble: zero response, no return calls, no acknowledging emails, no invitations to come in for an interview

A year after his arrest, a friend told him she’d searched for him online and found his mugshot. Was he in prison? Jesse T. was astonished and embarrassed. What was she talking about?

Google yourself, she said.

What he found: the arrest information had been published to a site called Mugshots.com. The site listed his full name, address, gender, and the charge for which Jesse T. had been arrested. It lacked any mention of the fact that he hadn’t been charged or convicted. Also on the site, he found a link to unpublisharrest.com. That led him to a phone number. When he called the 800 number, a man told him he’d need to fork over $399 to have his mugshot taken down.

“That’s illegal,” said Jesse T. The man laughed and hung up. Jesse T. called a total of five times, but all he got was a recording. Then, he got a call from an unlisted number. He turned on his recorder and answered.

According to court documents, this is the transcript from that call, which Jesse T. presented to police:

Jessie T.: Hello?

Unknown male: This third time tell you f**king bitch we never answer your calls again you’ve been permanently published faggot bitch.

Jessie T.: Hey, I’d like my stuff removed.

Call ended.

This is the business model: Mugshots.com publishes people’s mugshots, without their knowledge or consent, and then it extorts them for removal of the content.

But last week, Jesse T. was presented with a juicy fillet of poetic justice. Care for karma sauce?

According to a 25-page affidavit, between January 2014 and January 2017, Mugshots.com extorted at least 5,703 people throughout the US, for a total of approximately $2.5m.

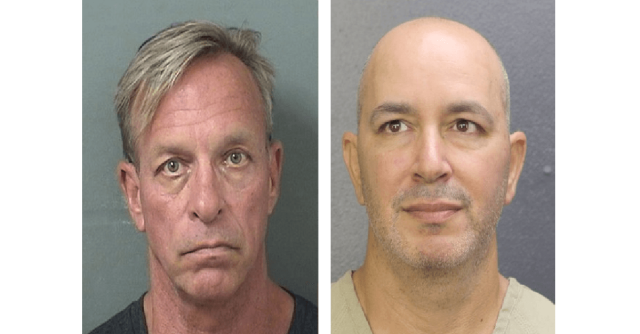

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra announced on Wednesday that two of four alleged owners and operators of Mugshots.com – Sahar Sarid and Thomas Keesee – were arrested in south Florida on a recently issued California warrant, on charges of extortion, money laundering, and identity theft.

Beyond those two alleged extortionists, the warrant also mentions Kishore Bhavnanie and David Usdan. Also on Wednesday, Bhavnanie was arraigned by a Pennsylvania state judge, with bail reportedly set at $1.86 million. Usdan is also reportedly in custody, according to Tania Mercado, a spokeswoman for the California Attorney General’s office.

According to Becerra’s press release, Mugshots.com mines data from police and sheriffs’ department websites to collect individuals’ names, booking photos and charges. It then republishes the information online without the individuals’ knowledge or consent. People who request removal go through what Jesse T. went through: they’re routed to a secondary website called Unpublisharrest.com and charged a “de-publishing” fee to have the content removed.

No payment? No dice: the criminal record information stays up until individuals shell out, regardless of the fact that, like Jesse T., some subjects have had charges dropped or were arrested due to mistaken identity or police error.

From the release:

Those subjects who cannot pay the fee may subsequently be denied housing, employment, or other opportunities because their booking photo is readily available on the internet.

The affidavit includes tales of harrowing ordeals told by other extortion victims. One woman, S. Shaw, was convicted on a drug charge and served her prison sentence. Shaw found that her mugshot was listed on Mugshots.com only when she was setting up a playdate between her daughter and a classmate. The classmate’s mom Googled Shaw, found her mugshot, and called off the get-together. My daughter’s not going to play with the daughter of a drug dealer, she said, and your daughter doesn’t even belong in the same school as mine.

When Shaw dug into Mugshots.com, she found that victims who paid the de-publishing fee found it fruitless: they found their mugshots had been published on other sites, as well.

Mugshots also allegedly tried to extort a widow of a man who went to jail for one night, wasn’t charged, and committed suicide four years later. When running an internet search on her son – who has the same name as his father – the father’s arrest record is the first hit.

That victim, Rosa S., told police that Mugshots.com tried to extort her for even more than that $399. She told police that “what Mugshots is doing is very ugly, and they are profiting from people’s pain.”

And humiliation. And lost job opportunities. And social ostracism. And lives filled with fear.

Becerra:

This pay-for-removal scheme attempts to profit off of someone else’s humiliation. Those who can’t afford to pay into this scheme to have their information removed pay the price when they look for a job, housing, or try to build relationships with others. This is exploitation, plain and simple.

Victims of Mugshots.com are being encouraged to file a police report with their local police department. Complaints can also be reported to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3).

Images courtesy of Palm Beach Sheriff’s Office and Broward Sheriff’s Office.