Thanks to John Shier for his help with this article.

Think of the big security stories of recent months.

Security holes like F**CKWIT and KRACK; a plethora of ransomware attacks ending in extortion; data breaches that were big, bigger or biggest…

…there are plenty of candidates for the story that got the most attention.

In contrast, phishing attacks rarely make the news these days, even though (or perhaps precisely because) there are so many of them.

Somehow, phishing seems to have turned into an “obvious” problem that everyone is expected to have experienced, learned from, got the better of, and moved on.

But phishing is still big business for cybercriminals: in the last week alone, for example, SophosLabs intercepted phishing attacks that abused the brands of many financial institutions.

Organisations that had their brands hijacked in this way in the past few days include: eBay, PayPal, VISA, American Express, Bank of America, Chase, HSBC, National Australia Bank – and that’s just a random subset of the list, in one industry sector.

Protecting your brand against abuse by phishers is, sadly, as good as impossible, especially if your brand is well-known and widely advertised.

Every time you send out an email of your own, or publish a blog article, or pen a PR statement, or put a logo on your website, you provide raw material for cybercrooks to copy-and-paste to produce simulacrums of their own.

Ironically, the less original and inventive they try to be, the more legitimate they’ll look, and the less likely they’ll be to introduce spelling, grammar and visual mistakes that clue you in to the deception.

Most phishing attacks are angling for something you know but are supposed to keep to yourself, such as:

- Usernames and passwords for existing accounts. With login credentials, the crooks can login themselves and take over.

- Credit card numbers, expiry dates and CVV codes. Crooks can use these to spend your money on themselves, or sell the data on to someone else.

- Personal information that you wouldn’t usually give out. Crooks can sell this on, or use it to open new accounts or take loans in your name.

Netflix brand hijack

Last week, a phishing campaign that hijacked the Netflix brand made big news.

Even if you back yourself to spot phishes from a mile away, it’s still worth reminding yourself from time to time what would go wrong if you were to make a mistake and click through.

So, we thought this one would be worth a quick “guided tour”, because the phish goes after all of the targets listed above: it tries to trick you into handing over your login details, your credit card data, your mugshot and your ID.

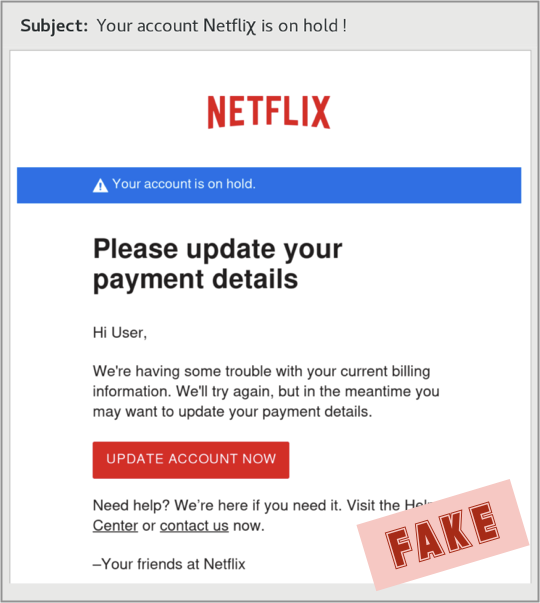

We’ve seen other people reporting different starting points for this phish, but here’s what we received to draw us in:

Note the simple trick, right there in the subject line, of not spelling out the brand-theft text “Netflix” exactly: the crooks wrote the X as the Greek letter chi, so that Netflix came out as Netfli𝛘.

Remember: never click login links or “update your account” links directly in emails, because you can’t easily tell where they lead.

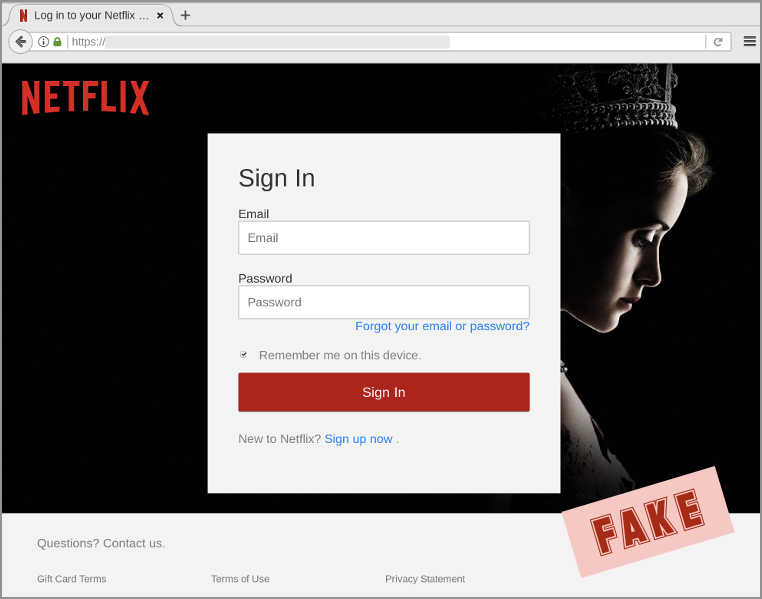

Keep your own record of where your favourite login pages are, and find your own way to them, precisely to avoid tricks like what comes next:

Note that this fake website has an HTTPS padlock, which is a convincing start.

But a padlock doesn’t mean you can automatically trust a site.

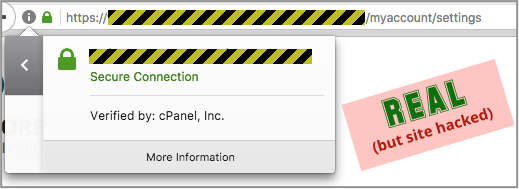

In this case, the crooks hacked into a site that already had a valid HTTPS certificate, and then uploaded their phishing pages so they’d show up with an air of believability.

On one hand, the hacked site is “secure”, because it really does belong to the company that is named in the certificate; on the other hand, it’s not secure at all, because it’s serving up unauthorised content:

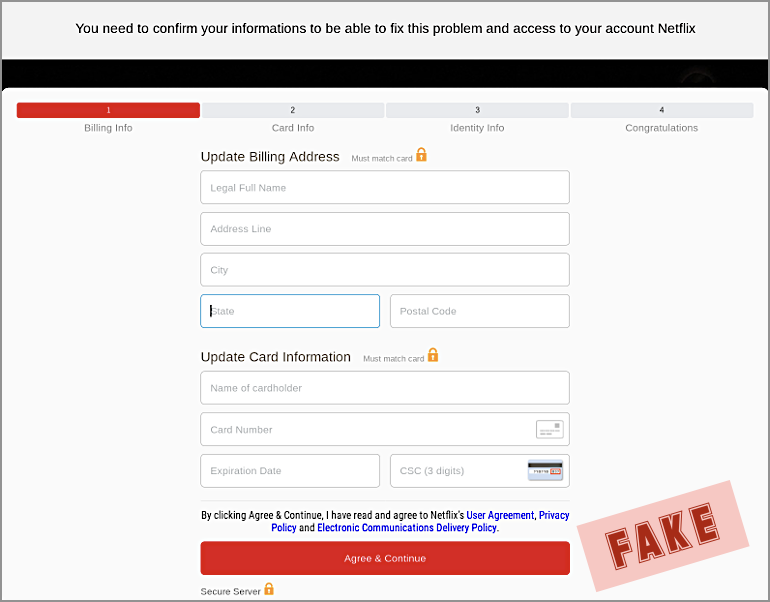

Having already handed over your username and password, the crooks also want your card details:

The crooks have added a grammatically incorrect sentence of their own at the top of the page that should tip you off, along with the incorrect URL:

You need to confirm your informations to be able to fix this problem and access to your account Netflix.

Ironically, the crooks didn’t need this sentence and could easily have left it out – so be sure to take advantage of anything that doesn’t look right, and treat it as a phishing warning sign.

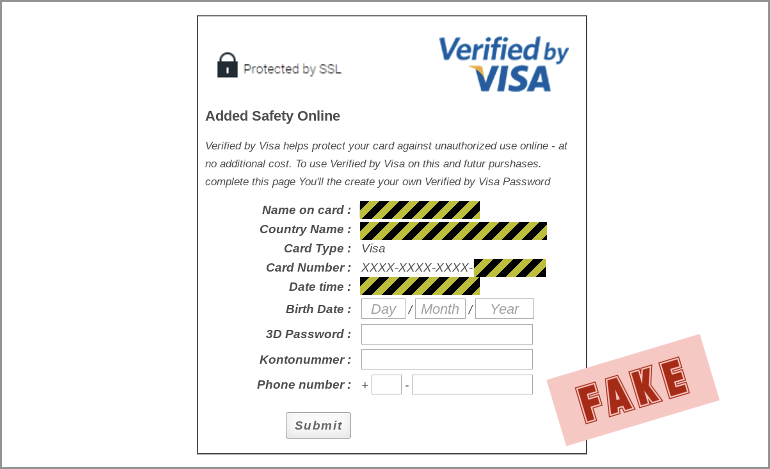

Next, there’s a fake Verified by VISA page that does nothing but repeat back to you what you already entered, but does so in a way that add a veneer of legimitacy, to try to keep you on the hook:

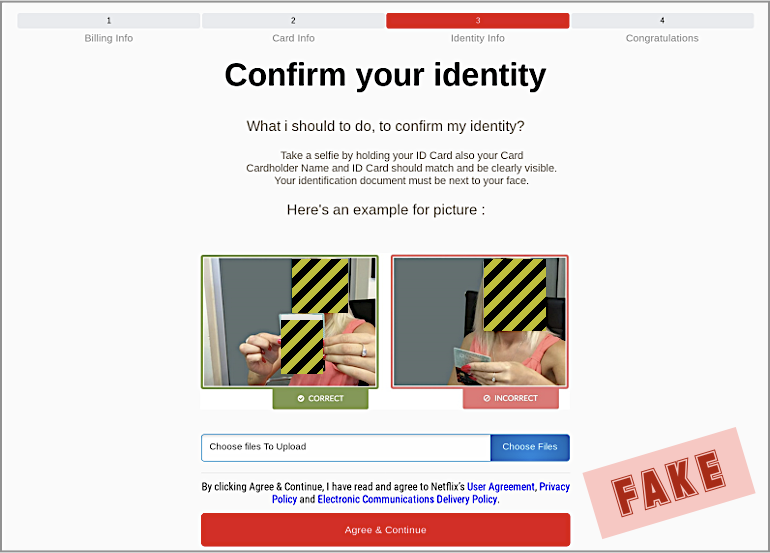

The crooks want to reassure you at this point, because they don’t want you to bail; they’re going for the triple play by asking for your mugshot and ID:

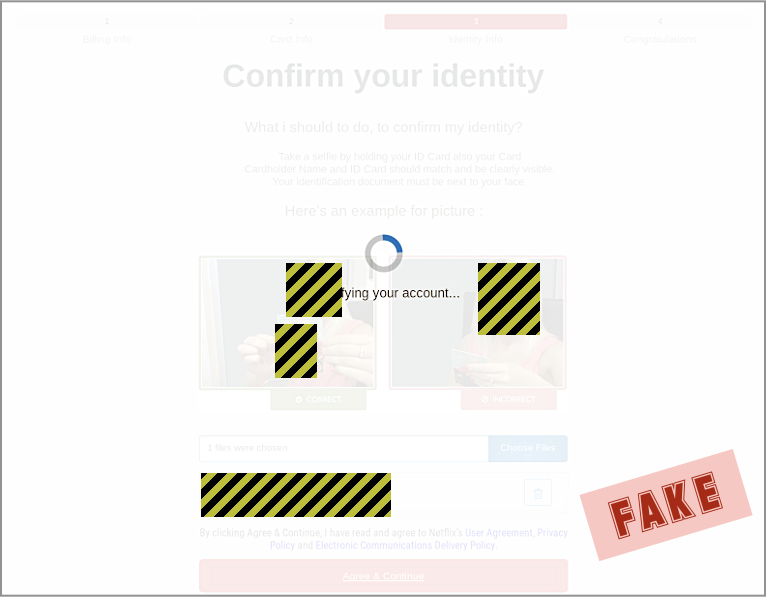

And, finally, you’re redirected to the real Netflix login page…

…where you should have gone in the first place, unaided by any “helpful” links in any email.

What to do?

- Never click on a login link or an account verification link in an email. If there is one, bail.

- Check for the HTTPS padlock. If there isn’t one, bail.

- But if there is a padlock, check the name of the site. If it’s not exactly what you expect, bail.

- Don’t ignore telltales such as spelling and grammar errors. If it looks wrong, bail.

- Guard your ID closely. If you’re asked for a selfie or ID when it isn’t absolutely necessary, bail.

Remember, if in doubt, DON’T GIVE IT OUT!

BT

You may want to clarify that first “What to do” tip as many times services will send an email verification for password reset or account creation. Most people will understand this as you will have initiated it therefore the time lines are in close proximity.

Paul Ducklin

That’s only in response to a login attempt, though, right? You’re not clicking *to* login. But I get your point – as password reset or account creation email will be a “verification” and it will have a special link.

Your last sentence is the advice: as long as you initiated it (and you didn’t click a link in an email to start with!)

Kyle

“One one hand, the hacked site is “secure”” gramer mistake? maybe this site is a phishing site :)

Love the article and your work, keep up the good job!

Paul Ducklin

Thanks for your kind words!

And thanks for spotting the typo – I’ve fixed it now.

Jeff Hall

What are expiry dates. We have expiration dates in the US. Are you a foreign company?

Paul Ducklin

Expiry date means exactly the same as expiration date. We’re a global company (headquartered in England) and in our articles, our house style is to go with the orthographic norms of the author. So our American writers utilize American spellings, while the rest utilise their own variants.

I’m the author, and I’ve only ever lived in Commonwealth countries, and every credit card I have ever had has said, “EXPIRY DATE”. Actually, that’s not strictly true. My current card, issued by a UK bank, says, “EXPIRES END”, and also has a start date on it (first card I’ve ever had with two dates).