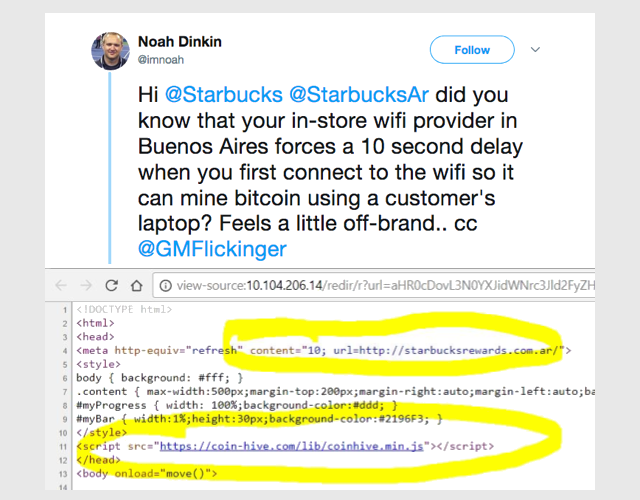

Remember how an Argentinian Starbucks store recently turned out to be doing JavaScript cryptomining on the side?

That’s where someone else uses your computer, via your web browser, to perform a series of calculations that help to generate some sort of cryptocurrency, and keeps the proceeds for themselves.

In that case, it seems to have been a unilateral decision by the Wi-Fi provider to include coin mining JavaScript code in the Wi-Fi registration page.

We’re guessing that the provider figured it would be OK to “borrow” approximately 10 seconds of CPU time whenever someone connected to the Wi-Fi, presumably as a way of earning a few extra pennies in return for providing free internet access:

(Just for the record, the tweeter was wrong above, inasmuch as the code was mining Monero, not Bitcoin – but the sentiment was spot-on.)

Starbucks wasn’t impressed, and “took swift action to ensure [the] internet provider resolved the issue”.

We’re guessing here, but we’re prepared to assume that this “swift action” involved a very short phone call in a rather loud voice.

But it’s not only the Wi-Fi operator or the coffee shop owner that you need to worry about.

If you join a public Wi-Fi network, and you don’t use a VPN, or stick to HTTPS websites, or both, then…

…anyone else in the coffee shop (or bus, or train, or hotel lobby, or wherever it is) at the same time can sniff out what you’re doing, and perhaps also trick you into seeing and doing something you didn’t expect.

Thanks to a “for academic purposes only” project called CoffeeMiner, rogues in your local cafe can now trick you into cryptomining, along with any other web-based cyberdodginess they might have in mind:

The project is the brainchild of a software developer from Barcelona who goes by the name Arnau Code, and if you ignore its potential for misuse (please read the disclaimer!), we think it’s a well-prepared tutorial about Man-in-the-Middle MitM) attacks.

If you’ve ever wondered why HTTPS (the padlock in your browser) really matters, and why every site really ought to use it instead of serving up content using plain old HTTP, you should look at Arnau’s article. Don’t just take it from us that HTTPS is about more than secrecy. The CoffeeMiner project is a good reminder that HTTPS is about authenticity and tamper-resistance, too – getting the right stuff from the right place.

A MitM attack is where someone else on the network gets to see your network requests before they set off to their final destination, and can intercept the replies before they get back to you.

Instead of talking directly to the site you’re expecting, you are effectively talking through a middleman, who can alter what you ask in the first place, and change what you see in reply.

Altering the answers is what CoffeeMiner does: through a variety of tricks, it intercepts your web traffic before it reaches the Wi-Fi access point in the coffee shop; it covertly fetches the web page you requested on your behalf; and it sneaks a line of coin-mining JavaScript in the reply.

In other words, every website you visit could, in theory, end up temporarily mining cryptocurrency for someone else.

Simply explained, Coffee Miner:

- Tricks your network card into thinking that the CoffeeMiner is the access point. The open source product

dnsiffis used for this part. - Passes on all your network traffic directly except for web requests.

- Pushes your web traffic into a man-in-the-middle proxy. The open source toolkit

mitmproxyis used here. - Inserts one line of coin-mining HTML into your web replies.

The CoffeeMiner code doesn’t actually inject coin mining code directly; instead it injects a line like this:

The IP number and port (in this example, 192.0.2.42:8000) is a web server running on the CoffeeMiner computer itself – in fact, it’s part of the CoffeeMiner toolkit – that serves up the actual cryptomining code of your choice. (Arnaud Code chose a widepspread miner known as CoinHive.)

What to do?

This isn’t really a lesson about cryptomining, though that certainly adds to the intrigue.

The problem here is that on an untrusted network (and that means almost every network you’ll ever use these days, because it’s hard to vouch for every user and every device attached at any moment), a rogue user can very easily mess with any web traffic that isn’t encrypted using HTTPS.

Without HTTPS, there is no confidentiality, so anyone can see what you are doing and saying; there is no identification, so you have no idea who’s replying; and there is no integrity, because you can’t tell when someone has tampered with what you’ve just downloaded, for example by stuffing a coin mining script into every web page.

As we mentioned at the start:

- Stick to sites that use HTTPS. A web-based MitM attack will almost always trigger a warning that you are connecting via an imposter server.

- Urge sites that don’t yet use HTTPS to start doing so. It’s a little bit more work, but worth the effort.

- Use a VPN if your work provides one. This encrypts all your network traffic back to head office, not just your web browsing.

By the way, if you want to run a VPN at home, and you have a spare computer handy, why not try the Sophos XG Firewall Home Edition? You get a free licence for everything the product can do, including anti-virus, web filtering, email security, IPS, plus a fully-fledged VPN.