You expect your pacemaker to keep your ticker ticking and nothing more. Little did Ross Compton know that day he is alleged to have burned down his house, that the data from his pacemaker would be the key witness against him.

Earlier this month a judge in Butler County, Ohio, decided that the evidence provided by Compton’s pacemaker could be presented at trial. The Journal-News tells us Compton is charged with setting fire to his house in September 2016, with the fire caused $400,000 worth of damages. Compton has a pacemaker and an external pump which he uses. The night of the fire he told police that he woke up, packed some items, broke a window, threw his cane and baggage out the window, and then left the house. He then collected his items and went to his car.

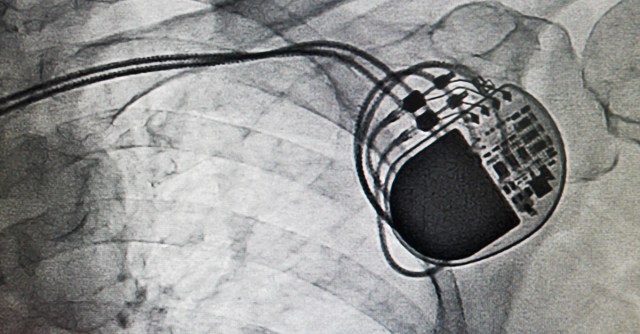

The police requested and received a search warrant to review the data stored in Compton’s pacemaker. The data collected showed Compton’s heart rate, cardio rhythms and pacemaker demand – both before and after the fire.

The prosecutor brought forward a cardiologist who opined in court:

It is highly improbable Mr Compton would have been able to collect, pack and remove the number of items from the house, exit his bedroom window and carry numerous large and heavy items to the front of his residence during the short period of time he has indicated due to his medical conditions.

The prosecutor noted that pacemaker data is analogous to subpoened health records of a defendant. The court agreed. Compton’s trial is set for December 4.

It is widely agreed that pacemakers, insulin pumps and the like were not designed with data security in the forefront. Indeed, security of medical devices is of immense importance. The Compton case raises the question of his pacemaker’s data were encrypted, would he be obliged to provide the key so that the information could be used against him?

While this may be the first instance that an embedded medical device’s data has been admitted into court, there have been instances where data from health wearables, FitBit specifically, has been admitted into court.

Back in April, a murder victim’s Fitbit contradicted her husband’s version of events. The prosecuting DA noted how the information was more accessible than other types of data, like DNA.

Writing in the May 2016 edition of the Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology, Nicole Chauriye raised important points with her paper, Wearable devices as admissible evidence: Technology is killing our opportunity to lie.

In the paper, she notes that consumer wearable health devices come under less stringent privacy rules than medical devices. For example, when an employer provides the employee with a consumer-grade device, the employee can expect the employer to have unencumbered access to the data from the device.

She goes on to highlight an example where a FitBit was used to provide demonstrable evidence that an individual’s ability to function had been diminished following a serious accident, and concludes that health and medical devices should be placed in the same category as cellphones and computers, which require a warrant to be legally searched (as was the case in the Compton case).

The bottom line is our implanted medical device or wearable health aid are going to tell their own stories about us based on our body’s telemetry.