Yesterday we wrote about a “Google Docs” phishing campaign that aimed to trick you into authorising a malicious third-party Gmail app so that it could take over your email account and your contact list for its own ends.

One of those ends seems to have been to spam out another wave of those same fraudulent emails to your friends and colleagues, in the hope of getting them to authorise the imposter app, and thus to send out another wave of emails, and another, and so on.

Technically, that made it more than just a “phish”, which we’ll define very loosely here as an email that aims to trick, coerce or cajole you into performing an authentication task, or giving away personal data, that you later wish you hadn’t.

The classic old-school example of a phish is an email that tells you that you have lost money to fraud, or gained money from a tax refund, so please use this web link to login to your bank account to sort this out. These days, however, the word phishing is generally understood much more broadly, describing any sort of misdirection that gets you to authorise or to give away something you should have kept private. Many users have learned to avoid login links in emails, so the crooks have broadened the range of threats and incentives by which they phish for access to your online life.

This week’s so-called “Google Docs” attack could spread all by itself, helped on by users giving it the permission it needed along the way, just like the infamous Love Bug virus from 2000, or the pernicious FriendGreetings adware from 2002.

Technically, then, that makes the “Google Docs” attack a virus, or more specifically a worm, which is a special sort of virus that spreads by itself, without needing pre-existing host files to hook onto.

You don’t get many of those these days.

Firstly, the crooks don’t really need self-spreading capabilities any more, given that they can as good as dial the malware yield they want, one victim at time, by spamming out attachments or web links until they hit their desired infection level.

Secondly, viruses often draw extra attention to themselves as plain malware, because they typically trigger the same sort of security alarms as non-replicating Trojan Horses, plus more.

How it worked

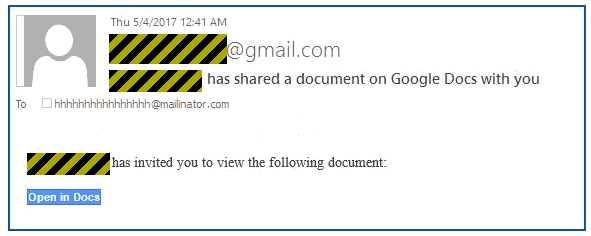

You’d start off by receiving an email that looked something like this:

You probably recognised the person whose name appeared on the email – because it almost certainly came from their account, via their contact list, even though they almost certainly never intended to send it.

If you clicked on the [Open in Docs] link, you wouldn’t actually end up at a Google Document.

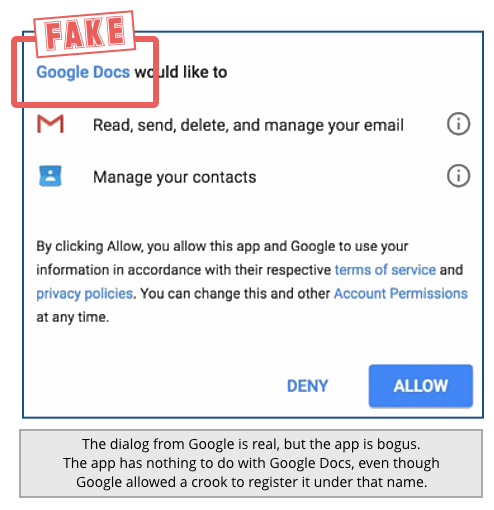

Instead, you ended up on a web page that asked you to install a Gmail app and authorise it to access both your emails and your contact list:

You ought to be have been suspicious by this time – after all, you shouldn’t need an app to handle Google Docs, because they’ll open fine in your browser anyway.

(Gmail apps are a bit like Facebook or Twitter apps – you give them permission to access your account in return for some added feature. One of the best known examples of this sort is Hootsuite for Twitter, which many of you may use.)

Neverthleless, we can understand if you were tempted to click on [Allow] to authorise the app, for two reasons:

- The email came from someone you knew.

- The app identified itself as “Google Docs”.

The truth was more sinister than this: somehow, Google allowed a crook to register a Gmail app called “Google Docs”, but it had nothing to do with Google, or with documents.

If you’re surprised that an app that seems so obviously intended to leech Google’s own brand got past Google’s security vetting process, you aren’t the only one.

If you clicked [Allow], you opened your account to all sorts of abuse, including the aforementioned side-effect of virally spamming out copies of the email to your own contacts.

Of course, a Gmail app that can access your contacts and emails can do much more sinister things as well, such as sniffing through your correspondence to steal data, fiddling with your contact list, and deleting incoming messages that might otherwise alert you to its presence.

What now?

If you didn’t get as far as clicking [Allow] for the imposter “Google Docs” app, you should be OK.

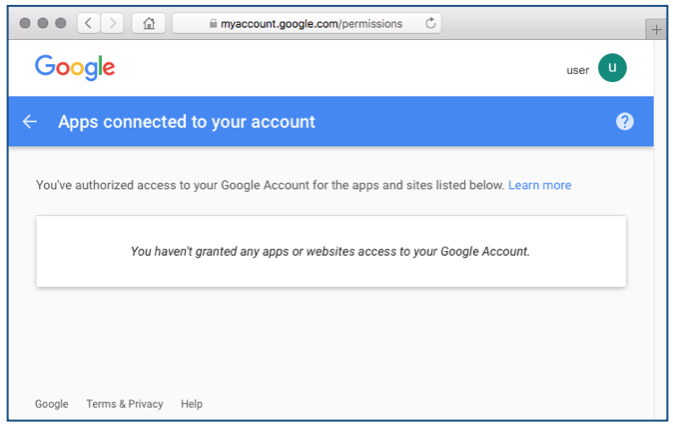

However, this is a good time to check your Google account to see which apps you have authorised to do what to your account.

Even if you didn’t authorise this fraudulent app, you may find other apps that you’ve forgotten about with too much power over your account.

The easiest way to check the apps that are connected to your account, once you’re logged in, is to go to https://myaccount.google.com/permissions.

That will show the list of apps that have power over your Google account: remove any apps that you aren’t sure of or that you no longer need.

If you did [Allow] this imposter app, you probably spammed your friends and colleagues with just the same sort of email you received in the first place, so don’t be surprised if they contact you to question or complain.

However, if you receive follow-up emails about this attack, don’t act on any of the demands they make about clicking links, changing settings and so forth – they could be from crooks trying to take advantage of the concern that this spamfest has caused.

What next?

The annoying thing here is that you didn’t need to be a Google Docs user to be affected, because the hack wasn’t against Google Docs.

The attack was really against Google’s whole “walled garden” ecosystem, where everything is supposed to be vetted for security up front.

So it’s astonishing that Google allowed anyone to register a third-party app called “Google Docs” at all – let alone to let a crook register a rogue app going by that name – because this effectively gave Google’s brand and imprimatur to an imposter.

If you are a Google account user, even if it’s only for Gmail, you probably want to wait for Google’s own investigation into how this happened.

Once you understand what extra checks the company will put in place to reduce the risk of this sort of abuse next time, you can decide how comforted you feel by Google’s response.

Having said that, just relying on Google being stricter about how apps describe themselves in future isn’t enough on its own.

With or without Google’s apparent endorsement, authorising a third party to do stuff to your Google account in this case, to send and read email and access your contacts) is a big step.

That’s a huge amount of power to hand out to someone else – try thinking of it like lending them your mobile phone for the rest of the month, or giving them a power of attorney over your credit card account.

So don’t be in a hurry to [Allow] a new app, even if it seems to be part of Google’s own brand, and no matter how cool and convenient it might sound.

Especially, don’t make such important decisions on the say so of a single email.

Take your time, ask people you trust for their opinion, and when it comes to your account, IF IN DOUBT, DON’T GIVE IT OUT.

LEARN MORE: Bogus student claims “Google Docs” email blast was his work ►

Julen

Hi!

Thanks for your posts. Some friends have a company and almost lost 40.000€ because the crooks read the mails (work mails) and tried to ask for payments in the name of the account owner (who happens to be the boss). So now, as you said it would be convenient to check for apps, change the password, close in all the devices and… is there anything else they should do to be certain the bad guys are not reading or sending more mails?

Thanks again.

Steve

Follow the steps in the article in the “What now?” section to make sure no application or service has access to the account.

Also, check the account settings to make sure emails aren’t being forwarded or copied somewhere.

Paul Ducklin

+1

If ever you think one of your accounts like Google, Twitter, Facebook and so forth has has someone else running around in it…

…it’s wise to revisit all your account settings in case the interlopers have changed something that might continue to leak data (or let them back in later, or even just embarrass you) even after you’ve otherwise kicked them out.

Dan R.

Also would like to add, that if you think there was a compromise, login and change your password and kill all logged in sessions for that application. After checking your activity log for any unusual posts that may contain further vectors of attack such as fake news links leading to malicious video links and fake flash plugins.